Killarney National Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Killarney National Park |

|

|---|---|

| Páirc Náisiúnta Chill Airne | |

|

IUCN Category II (National Park)

|

|

|

|

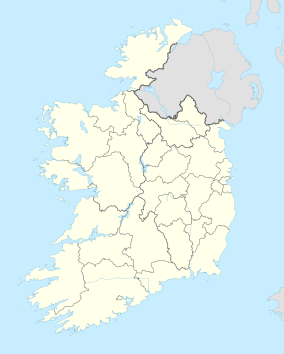

| Location | Killarney, Ireland |

| Nearest city | Cork |

| Area | 102.89 km2 (39.73 sq mi) |

| Established | 1932 |

| Governing body | National Parks and Wildlife Service (Ireland) |

Killarney National Park (Irish: Páirc Náisiúnta Chill Airne) is a special place in Ireland. It was the country's very first national park! It's located near the town of Killarney in County Kerry.

The park was created in 1932 when the Muckross Estate was given to the Irish Free State. Since then, it has grown much bigger. Today, it covers over 102 square kilometers (about 25,425 acres).

Killarney National Park is home to many different kinds of nature. You'll find the beautiful Lakes of Killarney here. There are also important oak and yew forests. High mountain peaks add to the amazing scenery.

This park is the only place on mainland Ireland where you can find a wild herd of red deer. It also has the largest area of natural, old forests left in Ireland. Because of its special habitats and many different species (including some rare ones), the park is very important for nature. In 1981, UNESCO named it a Biosphere Reserve. This means it's recognized worldwide for its unique environment.

The National Parks and Wildlife Service looks after the park. Their main goal is to protect nature. They want to keep the park's ecosystems as natural as possible. The park is also famous for its stunning views. It offers many ways for people to enjoy nature and visit.

Contents

- Climate and Geography: What Makes Killarney Special?

- A Look Back: Killarney's History

- The Beautiful Lakes of Killarney

- Amazing Woodlands: Killarney's Green Heart

- Boglands: Wild and Remote

- Flora: Killarney's Unique Plants

- Fauna: Animals of Killarney

- Protecting Killarney: Challenges and Efforts

- Visiting Killarney National Park

- See also

Climate and Geography: What Makes Killarney Special?

Killarney National Park is in the southwest of Ireland. This area is close to the most western point of the island. The park includes the famous Lakes of Killarney. It also has mountains like Mangerton, Torc, Shehy, and Purple Mountains.

The land in the park goes from about 22 meters (72 feet) high to 842 meters (2,762 feet) high. The park sits on a major geological line. This is where two different types of rock meet: old red sandstone and limestone. Most of the park has sandstone underneath. But you can find limestone rocks on the low eastern shore of Lough Leane.

Lough Leane is the biggest of the Killarney lakes. It has more than 30 islands! Many visitors enjoy boat trips to Innisfallen. This is one of the larger islands on Lough Leane.

The park has an oceanic climate. This means it's heavily affected by the Gulf Stream. Winters are mild, with an average of 6°C (43°F) in February. Summers are cool, with an average of 15°C (59°F) in July. The park gets a lot of rain. Light, showery rain is common all year. On average, it rains about 1,263 mm (50 inches) each year. About 223 days a year have more than 1 mm (0.04 inches) of rain.

The mix of different rocks, varied heights, and the Gulf Stream's influence creates a diverse environment. The park has many different habitats. These include bogs, lakes, moorland, mountains, rivers, and woodlands. You can also see exposed rocks, cliffs, and crags. Above 200 meters (656 feet), the sandstone mountains have large areas of blanket bog and heath.

A Look Back: Killarney's History

Early Times and Ancient Life

Killarney National Park is one of the few places in Ireland that has always had forests. This has been true since the last Ice age, about 10,000 years ago. People have lived here for at least 4,000 years, since the Bronze Age.

Archaeologists have found signs of copper mining on Ross Island. This suggests the area was very important to Bronze Age people. The park has many old sites. One is a well-preserved stone circle at Lissivigeen. Over time, the woods in the park have been changed by humans. This has caused a slow loss of different tree species.

Some of the most impressive old ruins are from the early Christian period. The most important is Inisfallen Abbey. These are the remains of a monastic settlement on Inisfallen Island in Lough Leane. It was started in the 7th century CE by St. Finian the Leper. Monks lived there until the 14th century.

The Annals of Inisfallen were written here. This book recorded the early history of Ireland. It's believed the monastery gave Lough Leane its name, which means "Lake of Learning."

Muckross Abbey was built in 1448 by Franciscan monks. It still stands today, even though it was damaged and rebuilt many times. People say "Friars Glen" on Mangerton Mountain was a place the monks would hide when the abbey was attacked. Muckross Abbey has a central courtyard with a huge yew tree. This tree is said to be as old as the abbey itself. Local leaders were buried at the abbey. Famous Kerry poets were also buried there in the 17th and 18th centuries.

After the Normans came to Ireland, the land around the lakes belonged to the McCarthys and O'Donoghues. Ross Castle is a 15th-century tower house on the shore of Lough Leane. It was once the home of the chieftain O'Donoghue Mór. The castle was made bigger in the 17th century. It has been fixed up and is now open to visitors.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the woods were used for local businesses. These included making charcoal, barrels, and leather. More trees were cut down in the late 1700s. The biggest reason for cutting oak trees was to make charcoal for iron factories. About 25 tons of oak were needed to make one ton of iron!

Tree cutting increased again in the early 1800s. This was probably because oak wood was very expensive. People started planting and managing the oak forests more. Many oak trees were cut down at Ross Island in 1803, Glena in 1804, and Tomies in 1805. These areas were then replanted with young oak trees. This is why most of the oak trees in the park today are about 200 years old.

The Herbert family owned the land on the Muckross Peninsula from 1770. They became rich from copper mines there. Henry Arthur Herbert and his wife finished building Muckross House in 1843. The Herberts faced money problems later, and Lord Ardilaun of the Guinness family bought the Muckross estate in 1899.

How Killarney National Park Was Born

In 1910, an American named William Bowers Bourn bought Muckross Estate. It was a wedding gift for his daughter Maud. She married Arthur Vincent. They spent a lot of money improving the estate between 1911 and 1932. They built beautiful gardens like the Sunken Garden and a rock garden.

Sadly, Maud Vincent died in 1929. In 1932, Arthur Vincent and Maud's parents gave Muckross Estate to the Irish state. They did this to honor Maud's memory. The 43.3 square kilometer (10,700 acre) estate was renamed the Bourn Vincent Memorial Park. The Irish government officially created the national park with a special law in 1932. This law said the park should be kept for "the recreation and enjoyment of the public." This memorial park is the heart of today's much larger national park.

At first, the Irish government couldn't give much money to the park. So, it mostly worked as a farm that was open to visitors. Muckross House itself was closed to the public until 1964.

Around 1970, people became worried about threats to the park. The Irish authorities looked at how other countries managed national parks. They decided to make Killarney bigger and officially call it a national park. This new park would be like the important "Category II" parks around the world. They also decided to create other national parks in Ireland.

Almost 60 square kilometers (14,800 acres) have been added to the park since 1932. This includes the three lakes, Knockreer Estate, Ross Island, Innisfallen, and other areas. The park is now more than twice its original size! As Ireland became richer, more money was given to the park.

The Beautiful Lakes of Killarney

The Lakes of Killarney are made up of three main lakes: Lough Leane (the lower lake), Muckross Lake (the middle lake), and the Upper Lake. These lakes are connected and cover almost a quarter of the park's total area. Even though they are linked, each lake has its own unique environment. The lakes meet at a popular tourist spot called the Meeting of the Waters. Fishing for brown trout and salmon has been a popular activity here for a long time.

Lough Leane is about 19 square kilometers (4,700 acres) in size. It's the largest of the three lakes and the biggest body of fresh water in the region. This lake has more nutrients than the others. It has become "eutrophic," meaning it has too many nutrients. This is due to phosphates from farms and homes getting into the lake. This has caused some algal blooms recently. To stop more pollution, officials are looking at how land is used around the lake. Water quality seems to have improved since phosphates were removed from sewage in 1985.

Muckross Lake is the deepest of the three lakes. It goes down to 73.5 meters (241 feet) deep. This is near where Torc Mountain's steep side meets the lake. This lake sits on the line between the sandstone mountains to the south and west, and the limestone to the north.

Lough Leane and Muckross Lake are both a bit richer in nutrients because of the limestone. There are many caves in the limestone near the lakes. These were made by waves and the slightly acidic water dissolving the rock. The biggest caves are on the northern shore of Muckross Lake.

From the Meeting of the Waters, a narrow channel called the Long Range leads to the Upper Lake. This is the smallest of the three lakes. It's located in the rugged mountains. Heavy rain can make this lake's level rise by up to a meter (3 feet) in just a few hours.

Muckross Lake and the Upper Lake have very clean water. It's slightly acidic and low in nutrients. This is because of water running off the sandstone mountains and bogs. They have many different water plants.

All three lakes are very sensitive to acid. This means they can be harmed by too many trees being planted in the areas that drain into them.

Amazing Woodlands: Killarney's Green Heart

Killarney has the largest area of natural, semi-wild forests left in Ireland. These forests are mostly made up of trees that are native to Ireland. Most of this woodland is inside the national park. There are three main types of woodland here. These include oak forests on sandstone, mossy yew forests on limestone, and wet alder forests near the lake edges. The oak and yew woodlands are very important worldwide.

Other types of woods, like mixed forests and planted conifer forests, are also in the park. The mixed forest on Ross Island has a very rich variety of plants growing on the ground.

Two big threats to the park's woodlands are animals eating too much (grazing) and the spread of rhododendron plants. Rhododendrons affect about two-thirds of the oak forests. There's a program to remove them. The yew forests have also been harmed by heavy grazing for many years.

Oak Woodlands: Home to Rare Plants

The park is perhaps most famous for its oak woodlands. They cover about 12.2 square kilometers (3,000 acres). These are the largest native oak forests left in Ireland. They are what remains of the forests that once covered much of the country. Derrycunihy Wood is probably the most natural oak wood in Ireland.

Most of the oak woodlands are on the lower slopes of the Shehy and Tomy mountains, next to Lough Leane. They are mostly made up of sessile oak trees. These trees like the acidic soil of the sandstone mountains. These woods are special because they have many different and rare plants, especially bryophytes (mosses and liverworts).

The oak woodlands usually have holly growing underneath the taller trees. Strawberry trees are also a special part of these woods. You can also find some scattered yew trees. The ground layer includes bilberry and woodrush.

Mosses, lichens, and filmy ferns grow very well here. This is because of the mild, humid climate. Some species found here only grow in the Atlantic region. The bryophytes in these woods are perhaps the best in Europe for this type of climate. Rare species found here include Cyclodictyon laetevirens and Daltonia splachnoides. Mosses, ferns, and liverworts often grow on the trunks and branches of oak trees.

Birds that live in the oak woods include blue tits, common chaffinches, and European robins. Mammals include badgers, foxes, pine martens, red deer, and red squirrels. Many insects also live here, like the purple hairstreak butterfly, which depends entirely on oak trees.

The introduced common rhododendron is a big threat to some oak woods. It has spread widely in Camillan Wood, even with efforts to control it.

Yew Woodlands: A Rare European Forest

The yew woodland in the park is called Reenadinna Wood. It's about 0.25 square kilometers (62 acres) in size. It sits on low-lying limestone rock between Muckross Lake and Lough Leane. Yew woodland is the rarest type of habitat in the park. Yew forests are very rare in Europe, mostly found in western Ireland and southern England.

Reenadinna Wood is one of the largest forests in the UK and Ireland dominated by common yew trees. It's the only important yew woodland in Ireland and one of only three pure yew woodlands in Europe. This makes it very important for nature. It's believed the wood started growing 3,000–5,000 years ago.

Yew is a native evergreen tree. It grows best in humid, mild climates like Killarney. The soil in the wood is usually thin. In many places, the trees grow their roots into cracks in the bare limestone. Yew trees create a dense shade, which stops other plants from growing on the forest floor. However, mosses are very common and grow well in the humid, cool conditions. In some parts, there are thick blankets of moss up to 152 cm (60 inches) deep!

Some trees in Reenadinna wood are 200 years old. There hasn't been much new growth of yew trees. Sika deer eating the young plants might be part of the reason. The thick shade from the yew trees might also stop new seedlings from growing.

Even though yew is poisonous, deer, rabbits, and other animals still eat its leaves and strip its bark. It's one of the most sensitive trees to grazing in Killarney. Sika deer have even killed yew trees by rubbing their antlers on them.

Wet Woodlands: Home to Deer

Wet woodlands, also called carr, are found in low-lying, swampy limestone areas near Lough Leane. They cover about 1.7 square kilometers (420 acres). This is one of the largest areas of this type of woodland in Ireland. The main trees here are alder, ash, downy birch, and willow. Areas that are sometimes covered by water have many different plants. These include grasses, rushes, and flowers like marsh bedstraw and water mint.

Red deer and sika deer use these wet woods a lot for cover. You can often see muddy "deer wallows" here. Rhododendrons are the biggest threat to these woodlands. They are spreading into the woods, growing on raised areas where the ground is too wet for their seedlings. Even though some have been cleared, they keep growing back.

Boglands: Wild and Remote

While the lower parts of the mountains have oak trees, above 200 meters (656 feet) the mountains have almost no trees. Instead, they are covered by blanket bog and wet heath. The bogs in the park have special plants. These include heather, bell heather, and western gorse. You can also find bilberry and large-flowered butterwort.

The bogs are also home to some important mosses and lichens. The remote mountain areas help Ireland's only remaining wild herd of native red deer survive. The bogs are threatened by grazing animals, peat cutting, fires, and tree planting.

Flora: Killarney's Unique Plants

The park has many interesting plant and animal species. This includes most of Ireland's native mammals. There are also several important fish species, like Arctic char. Many rare or scarce plant species grow here too. Some species found in the park have a "hiberno-lusitanean" distribution. This means they only grow in southwest Ireland, northern Spain, and Portugal. This is mainly because of the Gulf Stream's effect on Ireland's climate. The park is a biosphere reserve because of these rare species.

Many plant species in the park have unusual locations. They are only found in a few places in Ireland. These plants fall into four groups: arctic-alpine plants, Atlantic species, North American species, and very rare species. Atlantic species are mostly found in southern and southwestern Europe. Examples include arbutus, St Patrick's cabbage, and greater butterwort. North American species include blue-eyed grass and pipewort.

Bryophytes: Tiny Green Wonders

Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) grow very well in the park. This is partly because of the mild, wet climate. The park is very important worldwide for bryophytes. Many bryophytes found here are not found anywhere else in Ireland. Mosses, ferns (like filmy ferns), and liverworts grow in huge numbers. Many of them live as "epiphytes." This means they grow on the branches and trunks of trees.

Other Special Plants

The Killarney fern (Trichomanes speciosum) is probably the rarest plant in the park. It's a filmy fern that grows near waterfalls and in other damp places. It used to be common, but people picked it almost to extinction to sell to tourists. The few places it remains are in isolated mountain areas where pickers never found it.

The strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) is quite common in the park. However, it's one of Ireland's rarest native trees. It's found in very few places outside Killarney. In the park, it grows on cliff tops and at the edges of the woodlands around the lake.

Killarney whitebeam (Sorbus anglica) is a shrub or small tree. It grows on rocks near lakeshores. It is found only in Killarney. The more common Irish whitebeam (Sorbus hibernica) is also in the park.

The greater butterwort (Pinguicula grandiflora) is a carnivorous plant found in bogs. It eats insects to get nutrients that are missing from the bog soil. Its purple flowers bloom in late May and early June.

Irish spurge (Euphorbia hyberna) is an Atlantic species. In Ireland, it's only found in the southwest. In the past, the milky sap from its stem was used to cure warts. Fishermen used it to catch fish. The sap has things that stop fish gills from working.

The park also has many different types of lichens.

Fauna: Animals of Killarney

Mammals: From Deer to Voles

Most mammals native to Ireland live in the park. Also, some long-established introduced species are here. The bank vole was first seen in northwest Kerry in 1964. Its range has now grown to include the park. The pine marten is another special animal found here.

Deer: Killarney's Wild Herds

The park is home to Ireland's only remaining wild herd of native red deer (Cervus elaphus). There are about 900 of them. This is a big increase from fewer than 100 in 1970. They live mostly in the higher parts of the park, on Mangerton and Torc mountains. This herd has been in Ireland for 4,000 years. They were protected in the past by the Kenmare and Muckross estates.

Female deer (hinds) that are pregnant often go to the mountains to give birth in early June. Park staff tag the calves. Red deer and sika deer can breed together. However, no crossbreeding has been seen in the park. Keeping the native red deer herd pure is a high priority. Red deer are fully protected by law, so hunting them is not allowed.

Sika deer (Cervus nippon) were brought to the park from Japan in 1865. Their numbers have grown a lot since then. There are estimated to be up to 1,000 sika deer in Killarney National Park. They live in both open mountain areas and woodlands.

Bird Species: From Eagles to Waterfowl

The park has many different kinds of birds. It's very important for birds because it supports a wide range of species. 141 bird species have been seen in the park. These include birds that live in uplands, woodlands, and waterfowl that spend winter here. Several species that are rare in Ireland are present. These include the common redstart, wood warbler, and garden warbler. The red grouse and ring ouzel are on the IUCN Red List of species that need high protection.

The Greenland white-fronted goose, merlin, and peregrine falcon are also protected. Other notable birds in the park are the chough, nightjar, and osprey. The osprey sometimes flies through the park when it travels between northern Africa and Scandinavia. Old records suggest that ospreys used to nest here. Golden eagles also nested in the park once. But they disappeared around 1900 because of people disturbing them and hunting them.

The most common birds in the upland areas are meadow pipits, ravens, and European stonechats. Rare species include merlins and peregrine falcons.

Chaffinches and robins are the most common birds in the woodlands. Other birds that breed there include blackcaps and garden warblers. The rare redstart and wood warbler are thought to have a few breeding pairs in the park's woodlands.

Grey herons, little grebes, mallards, water rails, dippers, and common kingfishers live on the park's water bodies.

Lough Leane and the other lakes support birds that spend the winter here. These birds travel south from colder places. They include redwing, fieldfare, golden plover, and waterfowl like teal, goldeneye, wigeon, pochard, and whooper swan. The park's native bird populations are joined by migrant species in both winter and summer. A small group of Greenland white-fronted geese comes to winter on the bogs in the Killarney Valley. This group is important because it's one of the few left that feed only on bogland.

Other wintering waterfowls are coot, cormorant, mallard, pochard, teal, and tufted duck. Other species on the lakes are the black-headed gull, little grebe, and mute swan.

Birds that migrate from Africa in the summer include cuckoos, swallows, and swifts. Some birds appear only sometimes, for example, during stormy weather or very cold spells in Europe.

The park is also part of a project to bring back white-tailed eagles. This started in 2007 with the release of 15 birds. More eagles will be released over several years. This species had died out in Ireland in the 1800s because landowners hunted them. Even with some challenges, the program is continuing. Birds released here have now been seen in other parts of Ireland.

Fish Species: Hidden Gems of the Lakes

The Lakes of Killarney have many brown trout and salmon. Rare fish found in the lakes are Arctic char and Killarney shad. The lakes have natural stocks of brown trout and salmon that you can fish for, following Irish fishing rules.

The lakes contain Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus L.). These fish are usually found much further north in very cold lakes. They are a "relict species." This means they were left behind in the area after the last Ice Age. They show that the environment is still very clean. They are very sensitive to changes in the environment, especially being so far south in Ireland. The biggest threats to them are introduced fish species, pollution, and climate change.

The Killarney shad (or goureen) (Alosa fallax killarnensis) is a special type of twaite shad that lives only in the Lakes of Killarney. It's usually a sea fish, but this type lives only in the lake. It's rarely seen because it eats tiny plankton and so isn't often caught by fishermen. It's listed as a threatened species in Ireland.

Invertebrates: Tiny Creatures, Big Importance

Several unusual invertebrate species live in the Killarney valley. Some of these, like the northern emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora arctica), are usually found much further north in Europe. They are also thought to be "relict species" left after the last ice age. The northern emerald dragonfly, the rarest Irish dragonfly, is only found in the park. It breeds in shallow pools in bogs.

The oak woods in the remote Glaism na Marbh valley are a strong home for Formica lugubris Zett.. This is a type of wood ant that is rare in Killarney and in Ireland as a whole.

The Kerry Slug (Geomalacus maculosus) is a special slug found in southwest Ireland and Portugal. It comes out in Killarney's frequent wet weather to eat lichens on rocks and tree trunks. It's said to be the only slug that can roll itself into a ball! It is also a protected species.

Protecting Killarney: Challenges and Efforts

Killarney National Park faces several challenges in protecting its nature. One challenge is how close it is to Killarney town. Killarney is a very popular tourist spot, with hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. Most of these visitors spend time in the park. Careful planning is needed to make sure that protecting nature and allowing visitors to enjoy the park don't cause problems for each other.

Another challenge is the introduction of several exotic species (plants and animals not native to the area). These species have harmed Killarney's natural environments. The most noticeable are the common rhododendron (Rhododendron ponticum) and sika deer. The rhododendron has taken over large parts of the park. Sika deer eat too much of the plants on the forest floor. They also pose a possible threat to the native red deer. Both rhododendron and sika deer can stop native plants from growing back. A more recent, accidental, arrival is the American mink. It is now living in the park alongside the native otter. Animals that have disappeared from the park due to humans include the wolf and the golden eagle.

Fires caused by human activity happen quite often in the park. Even though the climate is wet, these fires can spread quickly over large areas. They usually don't burn through dense forests, but they can easily burn through open woodlands. The park was badly damaged by fires in April 2021.

The main use of land in the park is grazing by sheep. Deer grazing is also common. The woods in the park are currently being eaten too much by sika deer. Grazing has damaged many habitats on land. It has caused heath and blanket bogs to get worse and stops new trees from growing in the woodlands. In the mountain areas, erosion from grazing is made worse by the exposed land. More grazing by native animals like red deer and Irish hare has happened since their main natural predators, the wolf and golden eagle, died out. Grazing and disturbing plants also help the rhododendron spread.

The common rhododendron is perhaps the biggest threat to the park's nature. It's an evergreen shrub that originally came from the Mediterranean and Black Sea areas. Rhododendrons died out in Ireland thousands of years ago due to climate change. They were brought to the Killarney area in the 1800s and quickly took hold. They spread easily because they produce many tiny seeds. The rhododendron creates a dense shade on the ground. This stops native trees and plants from growing back. More than 6.5 square kilometers (1,600 acres) of the park are now completely covered by it. They have had a terrible effect in some parts of the park. Since light cannot get through the thick rhododendron bushes, very few plants can live underneath them. The park's oak woods are in long-term danger because they cannot grow new trees. There is a plan to control and get rid of rhododendrons in the park.

Visiting Killarney National Park

The park is open for visitors all year round. There is a visitor and education center at Killarney House. Places to see in the park include Dinis Cottage, Knockreer Demesne, Inisfallen Island, Ladies View, the Meeting of the Waters and the Old Weir Bridge, Muckross Abbey, Muckross House, the Muckross Peninsula, the Old Kenmare Road, O'Sullivan's Cascade, Ross Castle and Ross Island, Tomies Oakwood, and Torc Waterfall.

There are paths in the Knockreer, Muckross, and Ross Island areas. These can be used by cyclists and walkers. The Old Kenmare Road and the path around Tomies Oakwood offer great views over Lough Leane and Killarney. You can also take boat trips on the lakes.

Muckross House is a large Victorian mansion. It's close to the eastern shore of Muckross Lake, with the Mangerton and Torc mountains behind it. The house has been restored and attracts over 250,000 visitors each year. Muckross Gardens are famous for their collection of rhododendrons, azaleas, and exotic trees. Muckross Traditional Farms is a project that shows what Irish country life was like in the 1930s. Knockreer House is now used as the National Park Education Centre.

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional de Killarney para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional de Killarney para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |