Mandell Creighton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend and Right Honourable Mandell Creighton |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of London | |

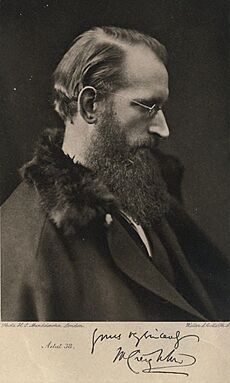

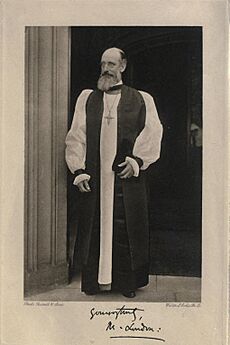

Creighton as Bishop of London, by Sir Hubert von Herkomer.

|

|

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Diocese of London |

| Elected | 1896 |

| Enthroned | January 1897 |

| Reign ended | 1901 (death) |

| Predecessor | Frederick Temple |

| Successor | Arthur Winnington-Ingram |

| Other posts |

|

| Orders | |

| Ordination | c. 1866 |

| Consecration | April 1891 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 July 1843 Carlisle, Cumberland |

| Died | 14 January 1901 (aged 57) |

| Buried | St Paul's Cathedral, London |

| Nationality | British |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Parents | Robert Creighton & Sarah Mandell |

| Spouse | Louise von Glehn (m. 1872) |

| Children | 7 children |

| Profession | Historian |

| Alma mater | Merton College, Oxford |

Mandell Creighton (5 July 1843 – 14 January 1901) was a British historian and a bishop in the Church of England. He was an expert on the Renaissance papacy, which is the history of the Popes during the Renaissance period.

Creighton was the first person to hold the Dixie Chair of Ecclesiastical History at the University of Cambridge. This was a new professorship created when history was becoming a more independent subject in universities. He also started and edited the English Historical Review, which is the oldest history journal in English.

Besides his academic work, Creighton had a career as a church leader. He served as a parish priest in Embleton, Northumberland. Later, he became a Canon Residentiary at Worcester Cathedral, then the Bishop of Peterborough, and finally the Bishop of London. People admired his balanced views and his understanding of the world. Even Queen Victoria praised him. Many believed he would have become the Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest position in the Church of England, but he died at age 57.

Creighton's historical writings received mixed reviews. People praised him for being fair and balanced. However, some criticized him for not taking a strong stand against bad actions in history. He believed that public figures should be judged by their public actions, not private ones. He also thought the Church of England was unique because of its English history. He felt it should reflect the views of the English people.

Mandell Creighton was married to Louise Creighton, who was an author and later worked for women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). They had seven children. Both Mandell and Louise were very interested in children's education. They even wrote many history books for schools together. Mandell Creighton was a very smart and energetic man. He represented many good and bad qualities of the Victorian era he lived in.

Contents

- Mandell Creighton's Early Life (1843–1857)

- School Days at Durham (1858–1862)

- Life as an Oxford Student (1862–1866)

- Teaching and Marriage (1867–1874)

- Vicar of Embleton (1875–1884)

- Cambridge Professor (1885–1891)

- Bishop of Peterborough (1891–1896)

- Bishop of London (1897–1901)

- Mandell Creighton's Legacy

- Mandell Creighton's Character

- Images for kids

Mandell Creighton's Early Life (1843–1857)

Mandell Creighton was born on July 5, 1843, in Carlisle, a city near the border of England and Scotland. His parents were Sarah (whose maiden name was Mandell) and Robert Creighton. His mother was from a farming family. His father, Robert, was a carpenter who built a successful business making furniture and decorating.

Mandell had a younger brother, James, and two sisters, Mary and Mary Ellen (Polly). Sadly, Mary died when she was very young. When Mandell was seven, his mother, Sarah, died unexpectedly. His father, Robert, never remarried. Robert raised the children with help from his unmarried sister.

Robert Creighton was a self-made man who worked hard. He taught his sons to be independent and work hard too. This helped Mandell make unusual career choices later in life. His brother James joined their father's business and became mayor of Carlisle twice. Polly, his sister, had a difficult childhood and couldn't finish school. But she spent her adult life promoting children's education. In 1927, she became the first woman to be given the freedom of the city of Carlisle.

The family lived above their shop. Their home was large but simple, with few decorations or books. Their father often lost his temper, which made the home atmosphere tense. There was a strong sense of duty, but not much open affection. Mandell's wife later thought that not having a mother made him feel less connected to his family.

Creighton started school at a small local school run by a strict teacher. He was often punished for being restless and mischievous. In 1852, he moved to the Carlisle Cathedral School. There, a inspiring headmaster, Revd William Bell, encouraged him. Mandell started reading a lot and doing very well in his studies. Other students would ask him for help with their classical studies. They even nicknamed him "Homer" because he was so quick at understanding things.

In November 1857, when he was 14, he took an exam for a scholarship to Durham Grammar School. He felt he had failed part of the exam because he wasn't prepared for Latin poetry. But the examiners saw how well he did overall and accepted him with a scholarship. In February 1858, Mandell Creighton left Carlisle for Durham.

School Days at Durham (1858–1862)

Students at Durham School had to attend church services at the old Durham Cathedral every Sunday. The cathedral's grand ceremonies made a lasting impression on Creighton. This experience became important in his religious life and later influenced his career choice.

The headmaster of Durham, Dr. Henry Holden, was a scholar and a reformer in education. He quickly noticed Mandell. With Holden's encouragement, Creighton started winning prizes in classical subjects, English, and French. In his last year, he became the head boy of the school. He liked this position because he wanted to influence others, especially younger boys. He tried to set a good example with his moral life.

Creighton had very poor eyesight and double vision. This meant he had to read with one eye closed. Because of his vision, he couldn't play many sports. Instead, he loved walking. He would often walk over twenty miles a day, sometimes for several days, with friends. These walks allowed him to explore and learn about local plants and buildings. He kept this habit for the rest of his life.

In 1862, Creighton tried to get a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford but didn't succeed. Next, he applied to Merton College, Oxford for a scholarship in classical studies. This time he was successful. Creighton arrived in Oxford in October 1862. He remained very interested in Durham School. A family story says that in 1866, he walked from Oxford to Durham in three days just to hear speeches at a school event.

Life as an Oxford Student (1862–1866)

Creighton's scholarship of £70 a year covered his tuition at Merton College, but not much else. He had to ask his father for money for other expenses, which was hard because his father was often grumpy. So, Creighton lived simply in college attic rooms for most of his time at Merton. In his final year, he shared rooms with George Saintsbury, who later became a famous writer and critic.

Even though his poor eyesight stopped him from playing cricket or football, he joined the college rowing team. He also continued his long walks. While many students took short walks around Oxford, Creighton organized much longer ones, sometimes lasting all day.

Creighton loved to read, not just the books for his classes. He read so much that he sometimes stayed at Oxford during holidays just to read more. He especially liked writers and poets like Carlyle, Browning, Tennyson, and Swinburne. He also became more aware of politics. He believed in individual freedom and joined the Oxford Union, a debating society. He was even elected its president. He was very good at informal conversations, discussing all sorts of topics.

Creighton strongly believed that everyone had a duty to influence and teach others as much as they could. He actively sought out people to guide. His friends at Merton nicknamed him "The Professor." In his second year, he and three other students formed a close group called "The Quadrilateral." This friendship was very strong, as was common at the time. Although Creighton had many friends, he didn't form close friendships with women during this period.

Academically, Creighton aimed for a top degree in literae humaniores, a classical studies program that attracted Oxford's best students. In his final exams, he earned a first-class degree. He then immediately joined the School of Law and Modern History. After studying all summer, he took those exams in Autumn 1866 and received a second-class degree. The examiners felt he hadn't mastered all the small details. However, since his first degree was so good, he was offered a teaching fellowship at Merton College on December 22, 1866. He had already decided to become a priest.

Teaching and Marriage (1867–1874)

In the mid-1800s, Oxford University was undergoing many changes. By the 1860s, these reforms reached the colleges. College tutors, who taught students individually, now also had to prepare them for university exams. These new tutors were often younger, talented graduates. Merton College was having problems with student unrest because of a lack of leadership among its teachers.

Creighton was popular with students, so he was seen as someone who could lead. He did this by talking to students and getting involved with them. He was given more responsibilities, which led to promotions and salary increases. After four years, his salary had more than doubled. He worked with another tutor to open college lectures to students from other colleges. This led to the creation of the Association of Tutors and university-wide lectures that any student could attend. These lectures influenced his future research. He later wrote that he ended up teaching "ecclesiastical, and especially papal history" because no one else did.

Religious beliefs were also changing a lot during the Victorian era. Many educated people who grew up in Christian homes started to doubt their faith. But Creighton's religious beliefs actually grew stronger. He wasn't interested in new scientific ideas like those of Charles Darwin, seeing them as too much guesswork. His friend Henry Scott Holland noted that it was unusual for a young, modern university teacher to be Christian at that time. After some discussion, Creighton was ordained a deacon by the Bishop of Oxford in 1870. He gave his first sermon in April 1871.

Creighton spent many holidays in Europe and fell in love with Italy. This led to his fascination with Renaissance Italy, which became his main area of study. He admired the aesthetic movement and decorated his Oxford rooms beautifully with William Morris wallpaper and blue china. His life was now very different from his frugal student days.

In early 1871, after a trip to Europe, Creighton attended a lecture by art critic John Ruskin. Afterward, he saw his friend Thomas Humphry Ward talking to a young woman wearing a yellow scarf. Yellow was Creighton's favorite color, and he was curious. He asked Ward about her, and her name was Louise von Glehn. Louise was the youngest daughter of a London merchant from Estonia. Soon, Ward invited Creighton and Louise to lunch. Within a few weeks, Louise was charmed by Creighton, and they became engaged before she left Oxford.

Their courtship involved visiting museums and looking at old Italian engravings. Creighton taught Louise Italian, and she helped him with his German. They planned to marry that winter. However, Merton College required its teaching fellows to be unmarried. On Christmas Eve, the college finally changed its rule and allowed four fellows to marry, including Creighton. Louise von Glehn and Mandell Creighton were married on January 8, 1872, in Sydenham, Kent. They honeymooned in Paris before returning to Oxford.

Like many scholars of his time, Mandell Creighton expected his wife to support his academic work. He believed he would be the main intellectual leader in their relationship. He wrote to her during their engagement that his life would involve many tasks, while her role would be more focused on him.

In the summer of 1873, the couple took their first trip to Italy together. It was during this trip that Creighton decided to focus his research on the Renaissance popes. Their family grew, with a daughter born in 1872 and another in 1874. With a growing family and a clear research plan, Creighton began to question if his teaching job at Merton was sustainable. He felt his teaching duties were draining his energy for research.

Around this time, an opportunity came up for a church position in a remote village in Northumberland. Merton College had the right to appoint the vicar there. Despite differing advice from Louise and his colleagues, Creighton made up his mind. In November 1874, when the college offered him the position of vicar of Embleton, Creighton eagerly accepted.

Vicar of Embleton (1875–1884)

The village of Embleton is on the North Sea coast in Northumberland, between Edinburgh and Newcastle upon Tyne. The vicarage, the vicar's house, was a large building. It included a fortified tower from the 14th century and later additions. It had many rooms for Creighton's growing family, guests, and servants. The parish included a few villages and about 1700 people. These were farmers, quarrymen, fishermen, women working in fish processing, and railway workers.

The Creightons missed the lively academic life of Oxford. But they slowly got used to their new home. With the help of a curate (another priest) whom Creighton paid himself, he set up a routine. This allowed him to do his church duties and write history. Every weekday morning, he spent four hours reading in the vicarage library. In the afternoons, Mandell and Louise would visit their parishioners' homes. They listened, gave advice, offered prayers, and sometimes gave homemade remedies.

They found the local people to be quiet, proud, and independent. The Creightons felt some locals lacked morals. So, they started a local chapter of the Church of England Temperance Society, which aimed to reduce alcohol use. This upset some people. Louise also organized meetings for the Mothers' Union and The Girls' Friendly Society. These groups aimed to help girls, for example, by encouraging them to stay in school until age fourteen.

The Creighton family continued to grow. Four more children were born during their years in Embleton. All the children were home schooled, mostly by Louise. Mandell Creighton was very interested in the local schools. He also examined students for other schools in the region. He started to develop his own ideas about children's education.

He was elected to local government groups, like the Board of Guardians, which managed poor laws, and the local health authority. In 1879, he took his first leadership role in the Church of England. He became the rural dean of Alnwick, overseeing clergy in nearby parishes. Later, he was appointed to examine candidates who wanted to become priests for the Bishop of Newcastle.

During their ten years in Embleton, the Creightons wrote fifteen books together. They both wrote history books for young people. Louise wrote a novel, and Mandell wrote the first two volumes of his major work, The History of the Papacy in the Period of Reformation. In these books, Creighton suggested that the Reformation became unavoidable because the Popes stopped earlier, milder reforms. The books were well-received and praised for their balanced approach. Lord Acton, a famous historian, praised Creighton's accuracy, especially since the books were written far from academic centers.

Creighton also wrote many book reviews and scholarly articles. Some of these were his first writings about the role of the Church of England in the nation. In the 1800s, the Church of England saw a decline in members. While some scholars believed the church and nation were the same, Creighton was one of the few who continued to argue this in the late 1800s.

In 1884, Creighton was asked to apply for a new professorship at the University of Cambridge, the Dixie chair of ecclesiastical history. He also received a fellowship at Emmanuel College. He got the job. On November 9, 1884, Creighton gave his last sermon at Embleton church. He later wrote, "At Embleton I spent ten years, and I have no hesitation in saying that they were the ten happiest years of my life." His parishioners found it hard to show their feelings. One woman simply said, "Well, if you ain't done no good, you've done no harm."

Cambridge Professor (1885–1891)

After arriving in Cambridge in late 1884, the Creightons were very busy with social events. Being back in academic society after ten years led to new friendships, especially for Louise. She became a lifelong friend with Beatrice Webb, a social reformer. Creighton met other important Cambridge figures, including historian Lord Acton and economist Alfred Marshall.

Creighton lectured twice a week at the university. He prepared a lot but spoke without notes. He also preached in the Emmanuel College Chapel. A colleague said he focused on teaching principles rather than just facts. Creighton also taught informal weekly classes for undergraduates at Emmanuel College. He supported Cambridge's two new women's colleges, Newnham and Girton. He taught informal weekly classes at Newnham. Two of his students, Mary Bateson and Alice Gardner, later became professional historians, mentored by Creighton.

In spring 1885, Creighton accepted an offer from Prime Minister William Gladstone. He was offered a residentiary canonry (a position for a priest) at Worcester Cathedral. This meant he had to live in Worcester for three months a year, which he could do during Cambridge holidays. So, the Creighton family moved between Cambridge and Worcester six times a year.

His time in Worcester made Creighton think about how cathedrals and local churches could work together instead of competing. He wrote scholarly articles on this topic. Worcester also showed Creighton the harsh realities of city life, which made him more aware of social issues. He joined an association that helped prison inmates and was moved by their difficulties. In a sermon, he spoke about how poor living conditions affect people's moral lives.

In November 1886, Creighton and Louise represented Emmanuel College at Harvard University's 250th anniversary in America. They met famous American writers and thinkers, including historian Francis Parkman and poet James Russell Lowell. Creighton received an honorary degree from Harvard.

In February 1887, volumes III and IV of Creighton's History of the Papacy were published. These volumes focused on specific popes like Sixtus IV, Alexander VI, and Julius II. Creighton's usual approach was to be balanced and understand people within their historical times. He didn't strongly condemn anyone, not even Alexander VI, whose bad reputation Creighton felt was partly because he didn't hide his flaws.

Earlier, in 1885, Creighton had agreed to be the first editor of a new journal, the English Historical Review. He asked Lord Acton to review his two new volumes for the journal. Acton's review was very critical and, in Creighton's opinion, unclear. This led to arguments between the two men about how history should be written. Acton believed historians should judge past actions, while Creighton preferred to explain them within their historical context. Acton famously wrote, "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." Acton's criticism made Creighton rethink his own views somewhat. He later wrote that the papacy, which was meant to promote morality, had sometimes allowed "the utmost immorality."

Bishop of Peterborough (1891–1896)

In December 1890, Prime Minister Lord Salisbury offered Creighton a position at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle. This was a special appointment, showing the Queen's personal preference. The Creightons were careful about court life, but Creighton accepted. Soon after, he received another letter from Salisbury. This new letter offered him the position of Bishop of Peterborough. The previous bishop had moved to York. Creighton was chosen because people thought his love for church ceremonies meant he had strong high church views, which would fit well in the Peterborough diocese. However, Creighton actually had more moderate, or "broad church," views. His moderation later made him popular with Queen Victoria.

Creighton felt it was his duty to accept the Peterborough appointment. This meant the end of his academic life, which made him and Louise sad. Louise's sadness lasted a long time. Creighton felt his life would now be about comforting others. He wrote to a friend, "No man could have less desire than I for the office of bishop. Nothing save the cowardliness of shirking from responsibility and the dread of selfishness led me to submit."

A few weeks before Creighton became bishop at Westminster Abbey in April 1891, he got sick. Soon after taking office at Peterborough Cathedral in May 1891, he got sick again with the flu. Both times, his recovery was long. The Peterborough diocese was huge, with 676 parishes, including the cities of Leicester and Northampton. Creighton tackled this challenge by visiting every part of it, just as he had done in Embleton. He traveled by train to distant parishes, stayed overnight with local priests, and held services in their churches. He spent very little time at home with his family during his first year. But by getting to know his clergy, treating them as equals, and quickly addressing their concerns, he became more popular.

This experience also helped him develop his religious views. Although he was personally liberal, he came to believe strongly that being English meant being Anglican. He saw other Christian groups as having strayed from the path and Roman Catholics as disloyal.

Creighton also wanted to understand the working-classes in his diocese better. The Leicester boot-and-shoe trade strike in 1895 gave him this chance. It started in March when employers locked out 120,000 workers. Creighton wrote an open letter to his clergy, explaining how serious the situation was. He urged them to work fairly to help the two sides talk. His biographer said Creighton acted as a go-between, sharing information and feelings from his local clergy. By late April, a compromise was reached. Creighton received much praise for this and gained a reputation as a skilled leader.

A year earlier, in 1894, the fifth and final volume of Creighton's History of Papacy in the Period of Reformation was published. It covered history up to the Sack of Rome in 1527. Creighton had little time to write it, and critics were generally disappointed. He had planned to continue the history further, but he didn't feel up to the task. Since the books didn't cover the full period in their original title, the publisher re-titled them in 1897 to reflect the shorter scope.

Despite this, Creighton remained a popular speaker. During his years in Peterborough, he gave many lectures, which were later published as books. These showed his wide range of interests. He gave lectures on "Persecution and Tolerance," "The Early Renaissance in England," and "The English National Character."

In 1896, Creighton represented the Church of England at the coronation of Czar Nicholas II in Moscow. He was chosen after the Archbishop of Canterbury and another bishop declined due to illness. Creighton loved grand ceremonies. He wore a bishop's coronation cope (a special cloak) borrowed from Westminster Abbey and carried his own mitre (tall hat) and pastoral staff. When he returned, he wrote a glowing report of the coronation for Cornhill Magazine. Queen Victoria read it and asked for several copies for the royal family.

Bishop of London (1897–1901)

On October 28, 1896, after the death of Archbishop Benson, Creighton received a letter from Prime Minister Lord Salisbury. It offered him the position of Bishop of London. There were rumors that this offer came with the promise of eventually becoming Archbishop of Canterbury. In January 1897, Creighton officially became the Bishop of London in a ceremony at St Paul's Cathedral.

Some other church leaders were suspicious of Creighton, thinking he was too academic or not serious enough. However, he quickly became well-regarded in government and royal circles, partly because of his worldly wisdom. Although high church office had taken him away from his academic career, Creighton now felt comfortable with the idea of reaching the top of the church. He hoped to return to scholarly work later.

One of Creighton's first actions as Bishop of London was to support the Voluntary School Bill of 1897. Years earlier, a law had created non-religious elementary schools funded by local taxes. But religious schools, called "voluntary schools," did not get this support. The new bill asked for taxpayer money to also go to voluntary schools. In March 1897, Creighton spoke in the House of Lords to support the bill, which eventually passed. Creighton strongly believed that all religious teaching should be specific to a denomination. He wrote that they only asked for parents' wishes to be considered for their children's religious education. Creighton also became president of the committee that documented London's main buildings and public art.

By 1898, Creighton was increasingly busy with a debate over ritual practices in the Church of England. When he arrived in London, he found that some clergy were upset by the practices of other high churchmen. These practices seemed to show Roman Catholic influence. This controversy had started after the Oxford Movement, which brought a Catholic revival within the Anglican church. One radical clergyman, John Kensit, complained that Creighton himself sometimes wore a cope and carried a mitre. Kensit wanted Creighton to take a stronger public stand against high church rituals like using candles and incense.

Creighton preferred to work quietly behind the scenes. He spoke with many high church clergy. He believed that the true Catholic Church included national churches like the Church of England, the Church of Rome, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. But he was firm that Anglican church services should follow the Book of Common Prayer. He wrote to his clergy that nothing should be done that affects the proper performance of the Church's services. However, Kensit and his supporters were not satisfied and threatened more public disruptions. Eventually, the two archbishops of the Church of England held a hearing and ruled against the use of candles and incense in August 1899. This seemed like a victory for the low church side. But the larger religious conflict continued for many years.

Throughout this time, Creighton managed the endless duties of his large diocese. In one year, he gave 294 formal sermons and speeches. He traveled to Windsor Castle and Sandringham to lead services for Queen Victoria. In 1897, he organized a special thanksgiving service outside St Paul's for her Diamond Jubilee. His important position also brought other responsibilities. He became a member of the Privy Council and a trustee of the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and many other organizations.

Creighton's health began to worry his family and friends. Starting in 1898, he had stomach pains. By 1899, these pains became more severe. By the summer of 1900, doctors suspected a stomach tumor. Creighton had two surgeries in December of that year, but they were not successful. In early January, he had two severe stomach bleeds, and his condition quickly worsened. Mandell Creighton died on January 14, 1901, at the age of 57. A nearby road, Creighton Avenue, was named after him.

Mandell Creighton's Legacy

On January 17, 1901, after a grand funeral at St Paul's Cathedral, Mandell Creighton was buried in the crypt. Royalty, politicians, academics, and ordinary people attended his funeral. It was the first time in 280 years that a Bishop of London had been buried in St Paul's. Newspapers and scholarly journals praised him as one of England's great historians and a very honest church leader. The Quarterly Review said it was rare to find so much intelligence and high moral standards in one person.

There is also a memorial to Creighton in Peterborough Cathedral. It is a large mosaic showing his image, details of his life, and the mottos "I determined not to know anything among you save Jesus Christ" and "He tried to write true history."

Today, Creighton is more famous as a historian than as a church official. His work is seen as an important part of British historiography (the study of historical writing). Many of his academic achievements, like starting the English Historical Review in 1886, were also important milestones for the field of history itself. Historian Philippa Levine notes that the Review was a key step in making history a professional academic subject. In 1884, several distinguished historians, including Creighton, received important academic positions. The following year, changes at Oxford and Cambridge universities made history an independent area of study.

Creighton is considered one of the first British historians with a focus on Europe. His major work, History of the Papacy in the Period of the Reformation, was one of the first big attempts to introduce British readers to truly modern European history. Overall, Creighton and his peers left a complex legacy. He was a very balanced scholar. Even his critic, Lord Acton, called Creighton's strength his "sovereign impartiality." Creighton saw himself as interested in actions, while he thought Acton was more interested in ideas. Although Creighton didn't think the popes were innocent, he insisted that public figures should be judged by their public actions, not private ones. He wrote, "I like to stand upon clear grounds which can be proved and estimated. I do not like to wrap myself in the garb of outraged dignity because men in the past did things contrary to the principles which I think soundest in the present."

However, Creighton's historical views, like those of his peers, were also shaped by their own culture and social position. Historians Robert Harrison, Aled Jones, and Peter Lambert point out that their focus on the "Englishness" of Britain's institutions often left out non-English groups from the main story of history.

Creighton's focus on real-world facts and situations also shaped his career as a church leader. He saw the Church of England not as an abstract idea, but as deeply connected to England, its people, and their history. He believed the church's form and beliefs were shaped by English history. He also thought the living church should reflect the current wishes of the English people. He wrote that the church's general direction "must be regulated by (the English people's) wishes. The Church cannot go too far from them."

Because of this view, Creighton was strongly against separating the church and the state. He saw them as two different sides of the same nation. He believed that trying to separate them would cause social problems in late-Victorian Britain. Many high-ranking clergy had connections and friendships with important public figures.

During his lifetime, Creighton received honorary doctorates from many universities, including Oxford, Cambridge, Harvard, and Trinity College, Dublin. A few years after his death, the Creighton lecture series was started at King's College, London. This lecture series celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2007.

Creighton became a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1897.

Mandell Creighton's Character

Mandell Creighton was a very smart man, sometimes puzzling to others. The philosopher Edward Caird said Creighton had "common sense in a degree which amounts to genius." At Cambridge, some colleagues were confused by his personality. When teaching or doing academic work, he was very sharp and clever. But at social gatherings, he was often outrageous and joked around, which students loved.

His relationship with Louise was complex. After he became Bishop of Peterborough, they often argued, sometimes bitterly, as a niece remembered. But they could also be very affectionate for their time. A nephew once saw Louise and the bishop in a passionate embrace in his study.

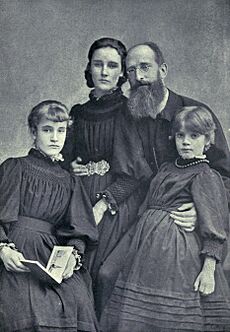

Creighton could be strict with his seven children. Once, he tied a daughter to a table leg with a rope to help her understand her mistake. But he also played with them, engaged in horseplay, and made up silly stories. Many years later, his children remembered these moments as highlights of their childhood. His children were Beatrice (born 1872), Lucia (1874), Cuthbert (1876), Walter (1878), Mary (1880), Oswin (1883), and Gemma (1887).

Throughout his life, Creighton loved going on long walks, which he called his "rambles." As his children grew older, the family's favorite outdoor activity became field hockey. Many visiting clergy at Fulham Palace found it hard to refuse Creighton's enthusiastic invitations to join in. The Creightons were frequent travelers, spending many holidays in Italy. For example, during their six years in Peterborough, they took nine trips abroad. Creighton was also a lifelong chain smoker. When author Samuel Butler received a letter from Creighton in 1893, he was immediately put at ease when he found some tobacco accidentally left in the envelope by the bishop.

Controversy seemed to follow him during his time as a bishop. He loved grand ceremonies, which made people think he had strong high church views. But when a high church priest argued that incense was needed to save souls, Creighton quickly replied, "And you think that souls like herring cannot be cured without smoke?" His moderate views, which opposed both radical evangelicals and conservative Anglo-Catholics, made him popular with Queen Victoria.

Creighton's work ethic was anything but moderate. He rarely refused offers of more responsibility. He often admitted to feeling fated to take on more duties and guilty about avoiding them. Perhaps recognizing this, a priest at St Paul's, welcoming Creighton to the London diocese in 1897, ominously remarked, "It is a frightful burden to lay on you: I hope you will use up everybody except yourself."

Images for kids

-

Durham Cathedral from Durham School chapel

-

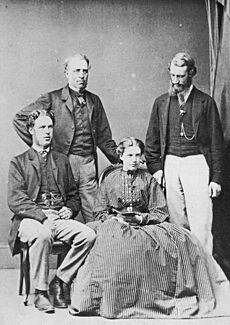

Mandell Creighton with the group, The Quadrilateral, at Merton College, Oxford, 1864. From left to right are seen: R. T. Raikes, M. Creighton, C. T. Boyd, and W. H. Foster.

-

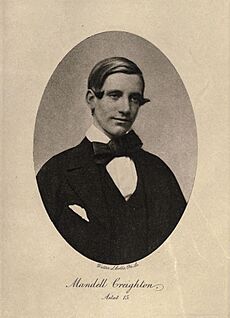

Mandell Creighton as a Merton College tutorial fellow in 1870, a year before he met Louise

-

The Embleton vicarage with its pele tower

-

Wood sculpture by Andrew Frost in Fulham Palace gardens showing Creighton climbing up the "Bishops' Tree"

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |