Nathaniel P. Banks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nathaniel P. Banks

|

|

|---|---|

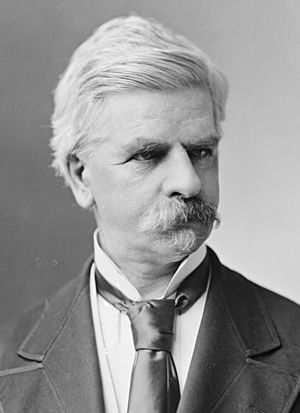

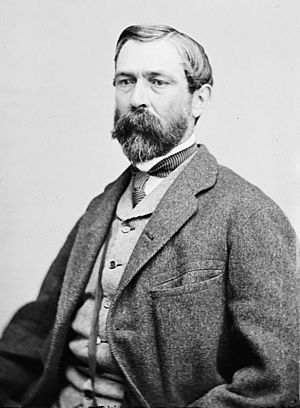

Portrait by Brady-Handy studio, c. 1865–1880

|

|

| 24th Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office January 7, 1858 – January 3, 1861 |

|

| Lieutenant | Eliphalet Trask |

| Preceded by | Henry Gardner |

| Succeeded by | John Albion Andrew |

| 21st Speaker of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office February 2, 1856 – March 3, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | Linn Boyd |

| Succeeded by | James Lawrence Orr |

| Chairman of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1871 Serving with Robert C. Schenck

|

|

| Speaker | James G. Blaine |

| Preceded by | Justin S. Morrill (1867) |

| Succeeded by | Austin Blair |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts |

|

| In office March 4, 1889 – March 3, 1891 |

|

| Preceded by | Edward D. Hayden |

| Succeeded by | Sherman Hoar |

| Constituency | 5th district |

| In office March 4, 1875 – March 3, 1879 |

|

| Preceded by | Daniel W. Gooch |

| Succeeded by | Selwyn Z. Bowman |

| Constituency | 5th district |

| In office December 4, 1865 – March 3, 1873 |

|

| Preceded by | Daniel W. Gooch |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Butler |

| Constituency | 6th district |

| In office March 4, 1853 – December 24, 1857 |

|

| Preceded by | John Z. Goodrich |

| Succeeded by | Daniel W. Gooch |

| Constituency | 7th district |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Nathaniel Prentice Banks

January 30, 1816 Waltham, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | September 1, 1894 (aged 78) Waltham, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party |

|

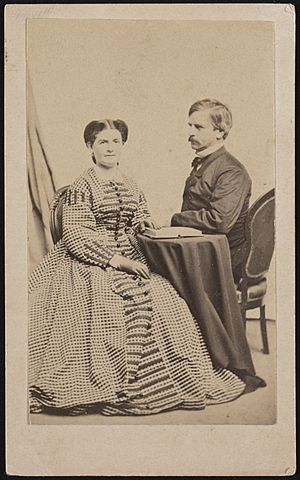

| Spouse |

Mary Theodosia Palmer

(m. 1847) |

| Children | 4, including Maude Banks |

| Profession | Military officer, workman |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign |

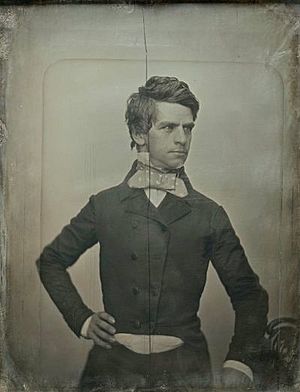

Nathaniel Prentice Banks (born January 30, 1816 – died September 1, 1894) was an important American politician from Massachusetts. He also served as a Union general during the Civil War.

Banks started his career as a millworker. He became well-known in local debate clubs. He entered politics when he was young. At first, he was a member of the Democratic Party. But his strong feelings against slavery led him to join the new Republican Party. Through this party, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives and became Governor of Massachusetts in the 1850s. He even became Speaker of the House after a very long election.

When the Civil War began, Abraham Lincoln made Banks a major general. This was unusual because Banks had no military training. He faced some tough times in battles, especially against Stonewall Jackson. Later, he commanded the Department of the Gulf in New Orleans. He worked to control the Mississippi River and helped with early efforts to rebuild Louisiana.

After the war, Banks returned to politics in Massachusetts. He served in Congress again. He supported the idea of Manifest Destiny, which meant the U.S. should expand across North America. He also helped with the Alaska Purchase and supported women's right to vote. In his later years, he became a U.S. marshal before his health declined.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Nathaniel Prentice Banks was born in Waltham, Massachusetts, on January 30, 1816. He was the first child of Nathaniel P. Banks Sr. and Rebecca Greenwood Banks. His father worked in a textile mill and became a foreman.

Banks went to local schools until he was 14. Then, he had to get a job to help his family. He started as a bobbin boy in mills in Waltham and Lowell. A bobbin boy replaced empty spools of thread with full ones. This job gave him the nickname "Bobbin Boy Banks," which stayed with him.

Even though he worked, Banks loved learning. He often walked to Boston on his days off to visit the Atheneum Library. He also went to lectures and formed a debate club with other mill workers. He wanted to improve his speaking skills.

Banks became involved in the local temperance movement, which worked against alcohol. His speeches caught the attention of Democratic Party leaders. They asked him to speak at their political events. Banks was good at speaking and presenting himself well.

His success as a speaker convinced him to leave the mill. He worked as an editor for two short-lived political newspapers. After they failed, he ran for the state legislature in 1844 but lost. He then got a job at the Port of Boston. This job gave him enough money to marry Mary Theodosia Palmer in 1847. She was a former factory worker. Banks ran for the state legislature again in 1847 but was not successful.

Early Political Career

In 1848, Banks finally won a seat in the state legislature. He helped organize voters in Waltham who were not controlled by the powerful Whig Party. At first, Banks was moderate about slavery. But he saw how strong the abolitionist movement was becoming. He then became a stronger supporter of ending slavery to help his political career.

Banks and other Democrats joined with the Free Soil Party. This group successfully took control of the legislature and the governor's office in 1850. Banks became the Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. His role as speaker and his effectiveness made him much more important.

Joining Congress

In 1852, Banks wanted to become a member of the United States Congress. He won a close election with support from the Free Soil Party. In 1853, he led the state's Constitutional Convention. This convention suggested changes to the state constitution, but voters rejected all of them.

In Congress, Banks served on the Committee of Military Affairs. He voted against the Kansas–Nebraska Act. This law overturned an earlier agreement about slavery. Banks used his skills to try and stop the bill from being voted on. His voters supported his stand against slavery.

In 1854, Banks joined the Know Nothing movement. This was a secret group that was against immigration. He won reelection to Congress easily that year. Banks, along with other leaders, was seen as important in the Know Nothing movement. However, he did not support their extreme anti-immigrant views.

In 1855, Banks helped create the new Republican Party. This party aimed to unite people from different groups who were against slavery.

Speaker of the House

In December 1855, the 34th U.S. Congress began. Democrats had lost their majority. Members from several parties who opposed slavery gradually supported Banks for Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. The election for Speaker was the longest and most difficult ever. It lasted from December 1855 to February 1856. Banks was finally chosen on the 133rd vote.

This victory was celebrated as the "first Republican victory." It greatly increased Banks's national fame. He gave important positions in Congress to anti-slavery members for the first time. He also helped with investigations into the Kansas conflict and the attack on Charles Sumner. Banks was praised for being fair and skilled in leading Congress.

Banks played a key role in 1856 in helping John C. Frémont become the Republican presidential candidate. Banks was even considered a possible presidential candidate himself. He refused the Know Nothing nomination, which went to former President Millard Fillmore. Banks actively supported Frémont, who lost the election. Banks easily won reelection to his own seat.

Governor of Massachusetts

In 1857, Banks ran for Governor of Massachusetts against the current governor. His nomination by the Republicans was debated. Some radical abolitionists opposed him because they thought he was too moderate. But Banks won the election comfortably.

One important action Banks took was dismissing Judge Edward G. Loring. Loring had ruled that a runaway slave, Anthony Burns, should be returned to slavery. The legislature passed bills asking for Loring's removal. Banks signed the third bill in 1858, removing Loring. This action earned him strong support from anti-slavery groups. He easily won reelection in 1858.

Banks's reelection in 1859 was affected by two main issues. One was a change to the state constitution. It required new citizens to wait two years before voting. Banks supported this change to please his Know Nothing supporters. The other issue was John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. More radical Republicans supported Brown, but Banks was more moderate.

After the election, Banks vetoed bills that would have allowed non-white people to join the state militia. This angered radical abolitionists. However, they could not override his vetoes.

Banks tried to get the Republican presidential nomination in 1860. But radical members of his state party disliked him. He did not get enough support from his state. He also tried to help another moderate Republican become governor, but the party chose the more radical John Albion Andrew, who won the election. Banks's farewell speech as governor called for peace and unity as the Civil War approached.

In 1860, Banks took a job with the Illinois Central Railroad. He moved to Chicago and worked to promote and sell railroad lands. He continued to speak out against the breakup of the Union.

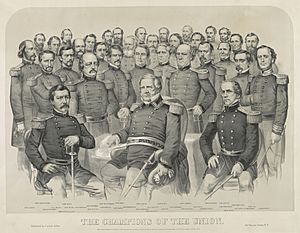

Civil War Service

As the Civil War was about to begin in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln considered Banks for a cabinet position. Lincoln decided against it because Banks had taken the railroad job. However, Lincoln appointed Banks as one of the first major generals of volunteers on May 16, 1861. Many professional soldiers were unhappy about this. But Banks was a well-known Republican. He helped the Union cause by attracting new soldiers and money.

First Military Command

Banks's first command was in eastern Maryland. This area included Baltimore, which had many people who supported the Confederacy. Baltimore was also a key rail link. Banks mostly stayed out of civil matters. He allowed people to express their Confederate views. But he made sure important rail connections stayed open. He also arrested the police chief and commissioners of Baltimore. He replaced the police force with pro-Union officers.

In August 1861, Banks was moved to western Maryland. There, he arrested lawmakers who supported the Confederacy before elections. This, along with letting his soldiers vote, ensured Maryland stayed loyal to the Union. Banks's actions helped keep Maryland in the Union throughout the war.

Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Banks's division was part of George McClellan's army. But it acted independently in the Shenandoah Valley. In March 1862, President Lincoln organized all troops into corps. Banks became a corps commander. He was in charge of his own division and another led by Brig. Gen James Shields.

After Stonewall Jackson was stopped at the First Battle of Kernstown on March 23, Banks was ordered to chase Jackson. The goal was to stop Jackson from helping the Confederate defenses at Richmond. Banks's men went deep into the valley. But their supply lines became too long. Lincoln then ordered them back to Strasburg.

Jackson then quickly marched down another valley. He met some of Banks's forces at the Battle of Front Royal on May 23. This made Banks retreat to Winchester. Jackson attacked again on May 25. The Union forces were not well-prepared and retreated in a rush across the Potomac River into Maryland. An attempt to trap Jackson's forces failed. Banks was criticized for not handling his troops well and for poor scouting.

Northern Virginia Campaign

In July, Maj. Gen John Pope took command of the new Army of Virginia. This army included Banks's forces. By early August, they were in Culpeper County. Pope gave Banks unclear orders. He told Banks to find out the enemy's strength, hold a defensive spot, and fight the enemy.

Banks was not as careful as he had been against Stonewall Jackson. He moved to meet a larger Confederate force. The Confederates were stronger in numbers and held the high ground near Cedar Mountain. On August 9, after an artillery fight began the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Banks ordered an attack on the Confederate right side. Banks's bold attack almost broke the Confederate line. But the Confederates fought well and received reinforcements. Banks thought it was one of his "best fought" battles.

Union reinforcements arrived, leading to a two-day standoff. The Confederates finally left Cedar Mountain on August 11. Stonewall Jackson said Banks's men fought well. Lincoln also said he trusted Banks's leadership. During the Second Battle of Bull Run, Banks's corps did not fight. Afterward, his corps joined the Army of the Potomac. On September 12, Banks was suddenly removed from command.

Commanding the Army of the Gulf

In November 1862, President Lincoln gave Banks command of the Army of the Gulf. He asked Banks to gather 30,000 new soldiers from New York and New England. Banks had good political connections to the governors of these states. The recruitment effort was successful.

In December, Banks sailed from New York with many new soldiers. He was to replace Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler in New Orleans, Louisiana. Banks was now in charge of the Department of the Gulf. Butler did not like Banks, but he welcomed him and told him about the situation. Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, doubted if replacing Butler with Banks was a good idea. Banks had to deal with Southern opposition and also with Radical Republicans who criticized his moderate approach.

Banks ordered his men not to steal. But the soldiers often disobeyed, especially near rich plantations. One soldier wrote that men would sneak away to break mirrors, pianos, and furniture.

Banks's wife joined him in New Orleans. She held fancy dinner parties for Union soldiers and their families. On April 12, 1864, she played the "Goddess of Liberty" at a party. She did not know then that her husband had lost the Battle of Mansfield three days earlier.

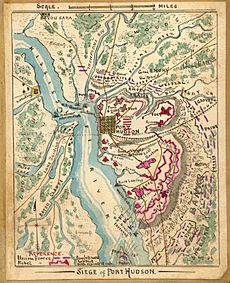

Siege of Port Hudson

Banks's orders included moving up the Mississippi River to meet Ulysses S. Grant. The goal was to take control of the river. Grant was attacking Vicksburg, Mississippi. Banks was ordered to secure Port Hudson, Louisiana before joining Grant. Banks did not move right away. The Port Hudson garrison was large, and his new soldiers were not ready. He was also busy managing the occupied parts of Louisiana.

He did send forces to take back Baton Rouge. He also sent a small group that briefly took Galveston, Texas. But they were driven out in the Battle of Galveston on January 1, 1863.

In March 1863, naval commander David Farragut wanted to sail past Port Hudson. He convinced Banks to make a land attack to distract the Confederates. Banks marched with 12,000 men on March 13. But he could not reach the enemy because his maps were wrong. He also had bad communication with Farragut. Farragut successfully sailed two gunboats past Port Hudson without Banks's support. Banks retreated to Baton Rouge, and his troops looted along the way. This event further hurt Banks's reputation as a military leader.

Banks was under pressure to show progress. He started operations to find a route around Port Hudson using the Red River. He reached Alexandria, Louisiana, but faced strong resistance from Confederate General Richard Taylor. Banks's army seized thousands of bales of cotton. Banks claimed he stopped supplies to Confederate forces. During these operations, Admiral Farragut gave command of naval forces to David Porter. Banks and Porter had a difficult relationship.

Following a request from Grant, Banks finally began the siege of Port Hudson in May 1863. Two attempts to storm the Confederate defenses failed badly. The first attack on May 27 failed because of poor scouting and lack of coordination. Banks continued the siege and launched a second attack on June 14. This attack was also poorly coordinated and resulted in many casualties.

The Confederate forces at Port Hudson surrendered on July 9, 1863. They gave up after hearing that Vicksburg had fallen. This meant the Union now controlled the entire Mississippi River. The siege of Port Hudson was also important because it was the first time African-American soldiers were used in a major Civil War battle.

In the fall of 1863, Lincoln and Chief of Staff Henry Halleck told Banks to plan operations against the Texas coast. This was to stop the French in Mexico from helping the Confederates. It was also to stop Confederate supplies from Texas. Banks first sent forces against Galveston, but they were badly defeated in the Second Battle of Sabine Pass on September 8. An expedition sent to Brownsville took control of the area near the Rio Grande in November.

Red River Campaign

Halleck encouraged Banks to lead the Red River Campaign. This was a land operation into northern Texas, which had many resources but was well-defended. Banks and General Grant thought the Red River Campaign was a distraction. They preferred to attack Mobile, Alabama. But political pressure led to the Red River plan.

The campaign lasted from March to May 1864 and was a major failure. Banks's army was defeated at the Battle of Mansfield (April 8) by General Taylor. They retreated 20 miles to fight again the next day at the Battle of Pleasant Hill. Even though Banks won a tactical victory at Pleasant Hill, he continued to retreat to Alexandria.

Part of Porter's large fleet became trapped above the falls at Alexandria because of low water. Banks and others approved a plan to build dams to raise the water level. In ten days, 10,000 troops built two dams. They managed to rescue Porter's fleet, allowing everyone to retreat to the Mississippi River. After the campaign, General William T. Sherman called it "One blunder from beginning to end." Banks lost the respect of his officers and soldiers for how he handled the campaign. The Confederates held the Red River for the rest of the war.

Reconstruction in Louisiana

Banks took steps to help President Lincoln's Reconstruction plans in Louisiana. When Banks arrived in New Orleans, some people were hostile because of Butler's actions. Banks changed some of Butler's policies. He freed civilians Butler had arrested and reopened churches. He also recruited many African Americans for the military. He started work and education programs for former slaves.

Banks believed plantation owners needed to be part of Reconstruction. So, the work program was not very friendly to African Americans. It required them to sign year-long work contracts. People who wandered without jobs were forced into public work. The education program was shut down after Southerners regained control of the city.

In August 1863, President Lincoln ordered Banks to oversee the creation of a new state constitution. In December, Lincoln gave him broad power to create a new civilian government. Banks worked to increase voter registration. After an election organized by Banks in February 1864, a Unionist government was elected in Louisiana. Banks told Lincoln that Louisiana would become "one of the most loyal and prosperous States."

A constitutional convention from April to July 1864 wrote a new constitution. It included the emancipation of slaves. Banks greatly influenced the convention. He insisted on including provisions for African-American education and at least partial voting rights.

By the end of the convention, Banks's Red River Campaign had failed. Major General Edward Canby took over military matters from Banks. President Lincoln ordered Banks to oversee elections under the new constitution in September. Then, he ordered Banks to go to Washington. Banks was to convince Congress to accept Louisiana's constitution and elected Congressmen. Radical Republicans in Congress opposed his efforts. They refused to seat Louisiana's two Congressmen in early 1865.

After six months, Banks returned to Louisiana to resume his military command under Canby. But he was caught between the civilian government and Canby. He resigned from the army in May 1865. He returned to Massachusetts in September 1865.

Banks received military honors after the war. He was elected commander of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts in 1867 and 1875. In 1892, he joined the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. This was a society for Union officers from the Civil War.

Post-War Career

When Banks returned to Massachusetts, he immediately ran for Congress. He won easily, even though the Massachusetts Republican Party opposed him. He served from 1865 to 1873. During this time, he led the Foreign Affairs Committee. He had to vote with the Radical Republicans on many issues. This was to avoid being seen as supporting President Johnson.

Banks strongly supported the idea of Manifest Destiny. He introduced laws to annex all of British North America (today's Canada). But this idea did not gain much interest. These proposals made him unpopular in Britain and Canada. But they were popular with his Irish-American voters. Banks also played a big part in getting the Alaska Purchase funding bill passed in 1868. Banks's financial records suggest he received a large payment from the Russian minister after the Alaska legislation passed.

In 1872, Banks joined the Liberal-Republican revolt to support Horace Greeley. Banks had opposed a party trend away from labor reform. This was important to his working-class voters. While Banks was campaigning for Greeley, another politician defeated him for reelection. This was Banks's first loss to Massachusetts voters. After his loss, Banks invested in a railroad company, hoping to make money.

In 1873, Banks successfully ran for the Massachusetts Senate. He was supported by a mix of Liberal Republicans, Democrats, and labor reform groups. He especially tried to win over labor groups. He supported shorter workdays. In that term, he helped pass a bill limiting work hours for women and children to ten hours per day.

In 1874, Banks was elected to Congress again. He served two terms (1875–1879). He lost in 1878 after rejoining the Republican Party. He was accused of changing his political views too often. After his defeat, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Banks as a United States marshal for Massachusetts. He held this job from 1879 to 1888. But he did not supervise his staff well. He got into legal trouble over unpaid fees.

In 1888, Banks won a seat in Congress again. But he did not have much influence because his mental health was failing. After one term, he was not nominated again. He retired to Waltham. His health continued to get worse. He died in Waltham on September 1, 1894. His death was reported nationwide. He is buried in Waltham's Grove Hill Cemetery.

Legacy and Honors

Fort Banks in Winthrop, Massachusetts, built in the late 1890s, was named after him. A statue of him stands in Waltham's Central Square. Banks Street in New Orleans is named after him. Banks Court in Chicago's Gold Coast neighborhood is also named for him. The village of Banks, Michigan, was named for him in 1871. His home in Waltham, the Gale-Banks House, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nathaniel P. Banks para niños

In Spanish: Nathaniel P. Banks para niños

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of Massachusetts generals in the American Civil War

- Massachusetts in the American Civil War

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

- Bibliography of American Civil War military leaders

- James Kendall Hosmer, American historian who served under Major-General Banks