George B. McClellan

Quick facts for kids

George B. McClellan

|

|

|---|---|

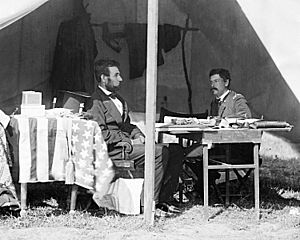

Photograph by Mathew Brady, 1861

|

|

| 24th Governor of New Jersey | |

| In office January 15, 1878 – January 18, 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | Joseph D. Bedle |

| Succeeded by | George C. Ludlow |

| Commanding General of the U.S. Army | |

| In office November 1, 1861 – March 11, 1862 |

|

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Winfield Scott |

| Succeeded by | Henry Halleck |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

George Brinton McClellan

December 3, 1826 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 29, 1885 (aged 58) West Orange, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Resting place | Riverview Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Mary Ellen Marcy

(m. 1860) |

| Relatives |

|

| Education | United States Military Academy (BS) |

| Signature |  |

| Nicknames |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

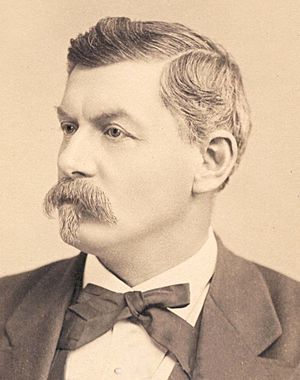

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an important American soldier and politician. He was a major general for the Union Army during the American Civil War. He also worked as a civil engineer and a railroad boss. Later in his life, he became the 24th Governor of New Jersey.

McClellan graduated from West Point. He fought well in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). After the war, he left the army to work on railroads. When the Civil War began in 1861, he rejoined the army. He quickly became a major general. He was key in training a strong army, which became the famous Army of the Potomac. For a short time, from November 1861 to March 1862, he was the top general of all Union armies.

McClellan led the Union army in the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia in 1862. This was the first big attack in the East. His goal was to capture Richmond, the Confederate capital. At first, he did well against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. But then, General Robert E. Lee took command. Lee's army defeated McClellan's in the Seven Days Battles. Even so, Lee's victory was costly for him.

General McClellan and President Abraham Lincoln did not trust each other. McClellan often spoke badly about Lincoln in private. After the Battle of Antietam in 1862, McClellan did not chase Lee's army. Because of this, Lincoln removed him from command in November.

McClellan never led an army in battle again. He ran for president in 1864 as a Democrat against Lincoln, but he lost. He later served as the 24th Governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881. He also wrote books, defending his actions during the Civil War.

Contents

Early Life and Training

George Brinton McClellan was born in Philadelphia on December 3, 1826. His father, Dr. George McClellan, was a famous surgeon. He founded Jefferson Medical College. George's family had roots in Scotland and England. His mother, Elizabeth Sophia Steinmetz Brinton McClellan, came from a well-known Pennsylvania family.

George first wanted to become a doctor like his father. He went to a private school and then the University of Pennsylvania. But his family decided that medical school for both him and his older brother was too expensive. So, after two years, he decided to join the military.

With help from his father, George was accepted into the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1842. He was only 15, even though the usual age was 16. At West Point, he was a very active and eager student. He loved learning about military strategies. He became good friends with some Southern cadets. This helped him understand the differences between the North and South that led to the Civil War. He graduated in 1846, at age 19, ranking second in his class. He became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Serving in the Mexican-American War (1846–1848)

McClellan's first job was with an engineering company. But he soon got orders to go to the Mexican–American War. He arrived in Mexico in October 1846. He was ready for action with many weapons. He was sad he missed the American victory at Monterrey. During a break in fighting, he got sick with dysentery and malaria. This kept him in the hospital for almost a month. He called malaria his "Mexican disease," and it came back in later years.

He worked as an engineer during the war. He was often under enemy fire. He was promoted for his service in battles like Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec. He also did scouting missions for Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, who was a close friend of McClellan's father.

His experiences in this war taught him important lessons. He learned that attacking from the side (flanking movements) was often better than direct attacks. He also saw how important it was to surround and cut off enemy cities (siege operations). He learned from General Scott how to balance military and political issues. He also saw how important it was to treat civilians well. McClellan also disliked volunteer soldiers and officers who didn't care about training.

Peacetime Army Work

After the war, McClellan went back to West Point. He led an engineering company there and helped train new cadets. He found peacetime army life boring, but he enjoyed the social events. In 1851, he was sent to Fort Delaware. In 1852, he joined an expedition to find the sources of the Red River in Arkansas. The expedition found the source of a river branch, which was named McClellan's Creek.

In 1852, McClellan published a book on bayonet fighting tactics. He had translated it from French. He also surveyed rivers and harbors in Texas. In 1853, he helped with the Pacific Railroad Surveys. These surveys were to find the best route for a transcontinental railroad. McClellan surveyed the northern part of the route. During this time, he sometimes disagreed with his superiors.

He also started dating Mary Ellen Marcy, the daughter of his former commander. She was called Nelly. Nelly turned down his first marriage proposal. She received nine proposals from different men, including his West Point friend, A. P. Hill. Nelly accepted Hill's proposal in 1856, but her family didn't approve, so he withdrew it.

In 1855, McClellan was sent to Europe as an official observer of the Crimean War. He traveled widely and met high-ranking military leaders and royal families. He watched the siege of Sevastopol. When he returned in 1856, he wrote a report about the European armies. He also wrote a book on cavalry tactics. He designed a saddle, which became standard for the U.S. horse cavalry. It is still used today for ceremonies.

Life as a Civilian

McClellan left the army on January 16, 1857. He used his railroad experience to become a chief engineer and vice president for the Illinois Central Railroad. Then, in 1860, he became president of the Ohio and Mississippi Railroad. He did well in both jobs. He expanded the Illinois Central and helped the Ohio and Mississippi recover from a financial crisis. Even though he was successful and earned a good salary, he missed military life. He kept studying old military strategies.

Before the Civil War, McClellan became involved in politics. He supported Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 election. He claimed to have stopped Republicans from cheating in a vote.

In October 1859, McClellan started dating Mary Ellen again. They married in New York City on May 22, 1860.

Civil War Service

Leading the Ohio Militia

When the Civil War started, McClellan's knowledge of large-scale warfare and railroads was very useful. His old report from the Crimean War was quickly published. This made him very popular. Governors from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York wanted him to lead their state militias. McClellan wanted to lead Pennsylvania's militia, but he didn't get the message in time. He stopped in Ohio and met Governor William Dennison. Dennison was impressed and offered him command of the Ohio militia. McClellan accepted on April 23, 1861.

Unlike some Union officers, McClellan did not want the government to interfere with slavery. Some Southern friends asked him to join the Confederacy, but he did not believe in states leaving the Union.

On May 3, McClellan joined the federal army again. He became commander of the Department of the Ohio. This meant he was in charge of defending Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and later parts of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Missouri. On May 14, he became a major general in the regular army. At 34, only Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott was higher in rank. McClellan's quick promotion was partly because he knew Salmon P. Chase, the Treasury Secretary.

McClellan quickly organized thousands of volunteers and set up training camps. He also thought about the overall war strategy. He wrote to General Scott on April 27, suggesting two plans. Both plans gave him a big role. Scott rejected both plans, saying they were too hard to supply. Scott suggested a plan to control the Mississippi River and block Southern ports. This plan was called the Anaconda Plan. It was slow, but it eventually became the way the Union won the war. McClellan and Scott's relationship became difficult.

Western Virginia Victories

Governor Dennison wanted McClellan to attack in western Virginia. Many people there wanted to stay in the Union. McClellan learned that important railroad bridges were being burned. As he planned to invade, he caused his first big political problem. He told the people there that his army would not interfere with their personal property, including slaves. He said he would "crush any attempted insurrection on their part." He soon realized he had gone too far and apologized to President Lincoln. The problem wasn't just that his statement went against the government's policy, but that he spoke so boldly outside his military role.

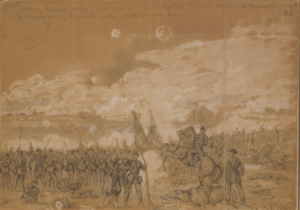

His troops quickly moved into the area. They won the Battle of Philippi, the first land battle of the war. McClellan's first personal command in battle was at Rich Mountain, which he also won. His victories, though small, made McClellan a national hero. Newspapers called him "Gen. McClellan, the Napoleon of the Present War."

Building the Army of the Potomac

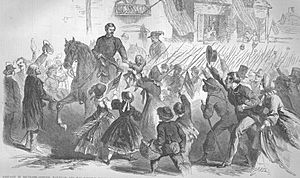

After the Union lost the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, Lincoln called McClellan to Washington. McClellan was seen as the only general who had won battles. He traveled by special train and was cheered by crowds along the way.

Many people believed McClellan was the right person to lead. On July 26, he was put in charge of the Military Division of the Potomac. This was the main Union force defending Washington. On August 20, he formed the Army of the Potomac, and he was its first commander.

During the summer and fall, McClellan organized his new army very well. He greatly improved their spirits by visiting and encouraging them often. This was a huge success. He built strong defenses around Washington, with 48 forts and many guns. The Army of the Potomac grew from 50,000 men in July to 168,000 in November. It became the largest army the U.S. had ever had.

However, McClellan often argued with the government and General Scott about war plans. McClellan did not like Scott's Anaconda Plan. He wanted a huge, decisive battle, like those fought by Napoleon. He suggested his army should grow to 273,000 men and "crush the rebels in one campaign." He wanted a war that would not harm civilians much and would not free slaves.

McClellan's dislike for freeing slaves caused problems. He was criticized by Radical Republicans in the government. He believed slavery was protected by the Constitution. He wrote that he would not "fight for the abolitionists." This put him against government officials.

A big problem for McClellan was that he always thought the Confederates had many more soldiers than they actually did. In August 1861, he believed the enemy had over 100,000 troops. In reality, they had far fewer. This made him very cautious. Historians say that McClellan almost always had twice as many soldiers as the enemy. For example, in September, the Army of the Potomac had 122,000 men, while the Confederates had 35,000 to 60,000.

His arguments with General Scott became personal. Scott was angry that McClellan would not share his plans. McClellan said he couldn't trust anyone in Washington to keep his plans secret. Scott became so frustrated that he offered to resign. Lincoln accepted Scott's resignation on October 18.

Despite these issues, the Army of the Potomac had high morale. They were very proud of McClellan, calling him "the savior of Washington." Many historians agree he was good at keeping the army's spirits up, especially after Union defeats.

Becoming General-in-Chief

On November 1, 1861, Winfield Scott retired. McClellan became the top general of all Union armies. Lincoln worried about him doing two big jobs at once, but McClellan said, "I can do it all."

Lincoln and many others in the North grew impatient. McClellan was very slow to attack the Confederate forces near Washington. A small Union defeat in October added to the frustration. In December, Congress formed a committee to look into how the war was being fought. This committee often criticized generals. McClellan was supposed to testify, but he got sick. His officers testified instead, and they admitted they didn't know McClellan's plans. This led to many calls for McClellan to be fired.

McClellan also hurt his own reputation by being rude to Lincoln. He privately called Lincoln names. On November 13, he even made Lincoln wait for 30 minutes at his house, only to be told the general had gone to bed.

On January 10, 1862, Lincoln met with his generals (McClellan wasn't there). Lincoln said, "If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time." On January 12, McClellan was called to the White House. He finally shared his plan: he wanted to move the Army of the Potomac by ship to Urbanna, Virginia. From there, they would march to Richmond. He didn't give many details, even to the new War Secretary, Edwin M. Stanton.

On January 27, Lincoln ordered all armies to attack by February 22. On January 31, he ordered the Army of the Potomac to march overland to attack Confederates at Manassas. McClellan wrote a long letter disagreeing with Lincoln's plan. He pushed for his Urbanna plan. Lincoln approved it, relieved that McClellan was finally ready to move. On March 8, Lincoln called a meeting with McClellan's officers to ask if they trusted the Urbanna plan.

Two more problems came up. The Confederate forces moved away from Washington. This made McClellan's Urbanna plan useless. McClellan changed his plan. His troops would land at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and march up the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond. This became the Peninsula Campaign. Then, McClellan was heavily criticized when people learned that the Confederates had tricked the Union army for months with fake cannons made of logs, called Quaker Guns.

On March 11, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan as general-in-chief. He was left in command of only the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln said this was so McClellan could focus on Richmond. McClellan felt this was a plot to make his campaign fail.

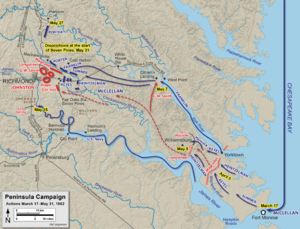

The Peninsula Campaign (1862)

McClellan's army started sailing from Alexandria on March 17. It was a huge fleet, carrying 121,500 men, 44 artillery batteries, and tons of supplies. An English observer called it the "stride of a giant."

The army's march up the Virginia Peninsula was slow. McClellan's plan to quickly capture Yorktown failed. He thought the Confederates had many more men than they did. Confederate General John B. "Prince John" Magruder tricked McClellan. He made his small force seem much larger by marching them around repeatedly. McClellan decided to lay siege to Yorktown, which took a lot of time.

After a month, McClellan learned that the Confederates had left Yorktown and moved towards Richmond. McClellan had to chase them without his heavy artillery. The Battle of Williamsburg on May 5 was a Union victory, McClellan's first. But the Confederate army escaped mostly intact.

McClellan also hoped the Union Navy could reach Richmond by the James River. But this failed when the Navy was defeated at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff on May 15. Confederates had cannons on a bluff and sank boats to block the river.

McClellan's army moved closer to Richmond over the next three weeks. They got within four miles of the city. He set up a supply base on the Pamunkey River.

On May 31, the Confederates attacked McClellan's army. General Johnston saw that the Union army was split by the Chickahominy River. He hoped to defeat them in pieces at Seven Pines. McClellan was sick with malaria and couldn't command in person. But his officers managed to stop the attacks. McClellan was criticized for not attacking back, which some thought could have captured Richmond. Johnston was wounded, and Robert E. Lee took command of the Confederate army.

McClellan spent the next three weeks moving his troops and waiting for more soldiers. Lee then launched a series of attacks called the Seven Days Battles. The first big battle, at Mechanicsville, was messy for Lee. But it scared McClellan. He thought he was even more outnumbered, believing he faced 200,000 Confederates. In reality, Lee's army had about 112,000 men, while McClellan had about 105,000.

Lee continued his attacks at Gaines's Mill. That night, McClellan decided to move his army to a safer base on the James River. This move surprised Lee and delayed his response. Historians note that McClellan's move to the James River helped his army. It allowed them to fight in a way that hurt the Confederate army badly.

But this also meant McClellan could no longer surround Richmond. He couldn't bring his heavy siege cannons without the railroad. In a message to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, McClellan blamed the Lincoln administration for his problems. He wrote, "If I save this army now, I tell you plainly I owe no thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington." Luckily for McClellan, Lincoln didn't see this message at the time because it was censored.

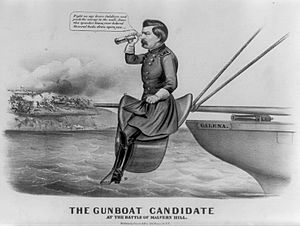

McClellan was also lucky that his army was mostly still together. He was often far from the fighting and didn't name a second-in-command. Historians have criticized him for being absent from battles like Glendale and Malvern Hill. At Malvern Hill, he was on a gunboat ten miles away. His friend, General Fitz John Porter, often ended up leading the army. When the public heard about him being on the gunboat, it was a big embarrassment.

McClellan's army gathered at Harrison's Landing. There were debates about whether to leave or attack Richmond again. McClellan kept asking for more soldiers. He also wrote a long letter to Lincoln, giving advice on the war. He continued to oppose freeing slaves. He hinted that he should be made general-in-chief again. But Lincoln responded by naming Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck to that job, without telling McClellan.

Back in Washington, a new army was formed under Maj. Gen. John Pope. Pope was ordered to march toward Richmond from the northeast. McClellan delayed sending his army back from the Peninsula. This meant his soldiers arrived while Pope's army was already fighting. McClellan wrote that Pope would be "thrashed." Lee moved many of his soldiers from the Peninsula to attack Pope. Pope was badly defeated at Second Bull Run in August.

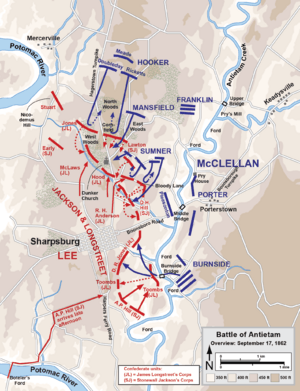

The Maryland Campaign (1862)

After Pope's defeat, President Lincoln reluctantly turned to McClellan again. Lincoln knew McClellan was good at organizing and training troops. On September 2, 1862, Lincoln put McClellan in charge of defending Washington. Many in Lincoln's Cabinet disagreed. But Lincoln said, "We must use what tools we have." He believed McClellan was the best at getting the troops ready to fight.

Northern fears of Lee's army continued. Lee launched his Maryland campaign on September 4. He hoped to gain support in the slave state of Maryland. McClellan began chasing Lee on September 5. He marched with six of his reorganized army corps. McClellan had about 60,000 fighting men, while Lee had fewer.

Lee split his forces into different groups. This was risky for a smaller army. But Lee was counting on McClellan's cautious nature. He thought McClellan's army would not be ready to attack for weeks. However, McClellan reacted faster than Lee expected.

Union soldiers accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders. It was wrapped around cigars in an abandoned camp. Special Order 191 showed that Lee's army was spread out. This made them vulnerable. The document was confirmed at McClellan's headquarters on September 13. McClellan was thrilled. He told a friend, "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home." He told Lincoln, "I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap."

Battle of South Mountain

McClellan's staff confirmed that Lee's orders were real. Within hours, McClellan sent cavalry to check if the Confederates had moved as the orders said.

Historians have debated whether McClellan acted quickly enough. Many say he delayed for about 18 hours before reacting. This delay allowed Lee to escape. However, some recent research suggests McClellan's army was already moving on September 13.

McClellan ordered his units to attack the passes in South Mountain. He broke through the Confederate defenses. This gave Lee just enough time to gather his men at Sharpsburg. The Union victory at South Mountain was important. It stopped Lee's plan to invade Pennsylvania and took the advantage away from him.

The Union army reached Antietam Creek on the evening of September 15. A planned attack on September 16 was delayed by fog. This gave Lee more time to prepare his defenses, even though his army was less than half the size of McClellan's.

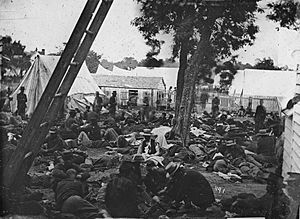

Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, was the bloodiest single day in American military history. The Confederate forces, though outnumbered, fought bravely. McClellan had many more soldiers, but he couldn't use them all effectively. He attacked in three separate waves, allowing Lee to move his defenders to meet each attack. McClellan also didn't use his large reserve forces. Historians point out that his two reserve corps were larger than Lee's entire army. McClellan was still convinced he was outnumbered.

The battle ended without a clear winner on the battlefield. The Union had more total casualties. But Lee was forced to retreat back to Virginia. McClellan wired Washington, "Our victory was complete." However, many were disappointed that McClellan hadn't crushed Lee's smaller army. McClellan's headquarters were too far back to control the battle directly. He didn't use his cavalry for scouting. He also didn't share his full battle plans with his corps commanders.

Despite being a draw on the battlefield, Antietam was a turning point for the Union. It ended Lee's first invasion of the North. It also allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which took effect on January 1, 1863. Lincoln had waited for a Union victory to issue the proclamation. This victory and the proclamation helped stop France and Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. McClellan didn't know that the plan for emancipation depended on his battle performance.

Because McClellan didn't chase Lee aggressively after Antietam, Lincoln removed him from command on November 5, 1862. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside took over the Army of the Potomac. McClellan wrote to his wife, "Those in whose judgment I rely tell me that I fought the battle splendidly... I feel I have done all that can be asked in twice saving the country."

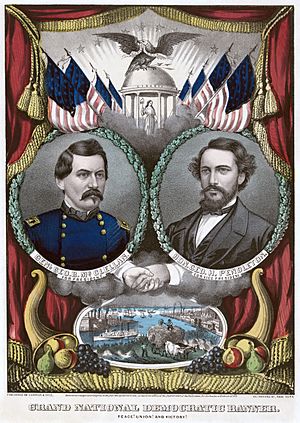

1864 Presidential Election

Secretary Stanton ordered McClellan to report to Trenton, New Jersey, but he was never given new orders. As the war continued, some wanted McClellan to return to command after Union defeats. But this was impossible because of opposition in the government. McClellan spent months writing a long report about his campaigns. He defended his actions and blamed the administration for not giving him enough soldiers. The War Department didn't want to publish his report because McClellan announced he was running for president as a Democrat in October 1863.

The Democrats nominated McClellan to run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election. He was still an active general. He didn't resign until election day, November 8, 1864. McClellan supported continuing the war and reuniting the country. However, he did not support ending slavery. The Democratic party platform, written by a "Copperhead" leader, called for an immediate end to fighting and talks with the Confederacy. McClellan had to disagree with his own party's platform, which made his campaign confusing.

The Democratic party was divided. The Republicans were united. Also, many Southern voters were not allowed to vote. Union military successes in the fall of 1864 sealed McClellan's fate. Lincoln won easily, with 212 electoral votes to 21. Lincoln also won the popular vote. Even though McClellan was popular with his soldiers, most of them voted for Lincoln.

After the War

After the war ended in 1865, McClellan and his family went to Europe. They didn't return until 1868. During this time, he stayed out of politics. Before he came back, some Democrats thought about nominating him for president again. But when Ulysses S. Grant became the Republican candidate, that interest faded.

McClellan worked on engineering projects in New York City. He was offered the job of president of the new University of California, but he turned it down.

In 1870, McClellan became chief engineer of the New York City Department of Docks. From 1872, he also served as president of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad. He and his family then spent another three years in Europe (1873–75).

In March 1877, McClellan was nominated to be the first state Superintendent of Public Works in New York. But the New York State Senate rejected him, saying he was "incompetent."

Governor of New Jersey

Becoming Governor in 1877

McClellan was living in West Orange, New Jersey in 1877. The New Jersey Democratic Party nominated him for governor. This surprised him, as he hadn't shown interest in the job. His nomination was mainly to stop another candidate from winning. He was nominated by a loud cheer from the convention.

In the election, he ran against William A. Newell, a Republican former governor. Newell accused McClellan of living in New York, which McClellan easily proved wrong. McClellan won the election by a large margin. Democrats also gained control of both parts of the New Jersey legislature for the first time since 1870.

His Time in Office

McClellan's inauguration was held outdoors because so many people wanted to see it. In his speech, he said the most important issue was helping the state recover from the Panic of 1873 (a financial crisis). He wanted careful spending to cut state taxes by half. By the end of his term, the state tax on residents was completely removed.

Soon after taking office, McClellan had disagreements with the State Senate over appointments. The legislature also passed some partisan laws to keep Democrats in power. These included redrawing voting districts and stopping college students (who often voted Republican) from voting. This led to Republicans winning control of both parts of the legislature for the rest of McClellan's term. This limited what he could do.

McClellan's time as governor was careful and traditional. Few big laws passed. But the ones that did, like ending the state tax and improving the National Guard, were very popular.

Besides tax cuts, McClellan wanted to create a Bureau of Statistics for Labor and Industries. He also wanted to start an agricultural experiment station to modernize farming. Both ideas became law. His administration also stressed the importance of education. He wanted to expand the state library and offer trades training for young men in public schools.

McClellan also used his military experience to improve the New Jersey National Guard. He made it more disciplined and better organized. During his time, two companies got new machine guns. A new battalion was formed, and regular rifle practice began. New uniforms were also provided.

Later Years and Death

The last part of his political life was his strong support for Grover Cleveland in the 1884 presidential election. He wanted to be Secretary of War in Cleveland's cabinet. But Senator John R. McPherson, who had opposed McClellan for governor, blocked his nomination.

McClellan spent his final years traveling and writing. He wrote his memoirs, McClellan's Own Story, which was published after he died in 1887. In it, he strongly defended his actions during the war. He died unexpectedly from a heart attack at age 58 in Orange, New Jersey. He had been having chest pains for a few weeks. His last words were, "I feel easy now. Thank you." He was buried at Riverview Cemetery in Trenton.

Family Life

McClellan's son, George B. McClellan Jr. (1865–1940), was born in Dresden, Germany, during the family's first trip to Europe. He was known as Max. He also became a politician. He served as a U.S. Representative and as Mayor of New York City from 1904 to 1909.

McClellan's daughter, Mary (1861–1945), married a French diplomat. She lived much of her life abroad.

McClellan's wife, Ellen, died in Nice, France, in 1915 while visiting her daughter Mary.

Legacy and Remembrance

The New York Evening Post wrote in McClellan's obituary, "Probably no soldier who did so little fighting has ever had his qualities as a commander so minutely, and we may add, so fiercely discussed." This debate continues even today. McClellan is often ranked among the lower Civil War generals. However, historians still argue about his skills. He is always praised for his organizing abilities and for how well he got along with his troops. They affectionately called him "Little Mac." Others sometimes called him the "Young Napoleon."

One reason McClellan's reputation has suffered is his own memoirs. Historian Allan Nevins wrote that McClellan "frankly exposed his own weaknesses" in his book. Doris Kearns Goodwin says his personal letters show he often praised himself too much. His book, McClellan's Own Story, was published after he died. It included parts of his wartime letters to his wife, where he shared his true feelings.

Robert E. Lee, when asked who was the best Union general, reportedly replied, "McClellan, by all odds!"

While McClellan's reputation has declined, some historians believe he has been unfairly judged. They argue that because he was a conservative Democrat, radical Republicans tried to hurt his military operations. They also say that since radical Republicans won the Civil War, they wrote the history to make McClellan look bad. Some believe historians tried to shift blame from Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to McClellan for early military failures. Others suggest Lincoln and Stanton deliberately weakened McClellan because he wanted a less destructive end to the war. These historians claim McClellan is criticized more for his personality than for his actual performance in battle.

Several places and things are named after George B. McClellan. These include Fort McClellan in Alabama and two mountains in Washington state, McClellan Butte and McClellan Peak. There is a bronze equestrian statue honoring him in Washington, D.C. Another statue is in front of Philadelphia City Hall. The McClellan Gate at Arlington National Cemetery is also dedicated to him. McClellan Park in Maine was donated by his son and named after the general. Camp McClellan in Iowa was a Union Army training camp during the Civil War. The McClellan Fitness Center at Fort Eustis, Virginia, is near where he fought in the Peninsula Campaign.

The Fire Department of New York had a fireboat named George B. McClellan from 1904 to 1954. This boat was actually named after his son, who was the Mayor of New York City when the boat was launched.

Images for kids

Electoral History

1864 Democratic National Convention:

- George B. McClellan – 174 (77.3%)

- Thomas H. Seymour – 38 (16.9%)

- Horatio Seymour – 12 (5.3%)

- Charles O'Conor – 1 (0.4%)

1864 United States presidential election

- Abraham Lincoln/Andrew Johnson (National Union) – 2,218,388 (55.0%) and 212 electoral votes

- George B. McClellan/George H. Pendleton (Democratic) – 1,812,807 (45.0%) and 21 electoral votes (3 states carried)

New Jersey gubernatorial election, 1877:

- George B. McClellan (D) – 97,837 (51.7%)

- William Augustus Newell (R) – 85,094 (44.9%)

Selected Writings

- The Mexican War Diary of George B. McClellan (William Starr Myers, Editor). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1917.

- Bayonet Exercise, or School of the Infantry Soldier, in the Use of the Musket in Hand-to-Hand Conflicts (translated from the French of Gomard), 1852. Reissued as Manual of Bayonet Exercise, Prepared for the Use of the Army of the United States. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862.

- The Report of Captain George B. McClellan, One of the Officers Sent to the Seat of War in Europe, in 1855 and 1856, 1857. Reissued as The Armies of Europe, Comprising Descriptions in Detail of the Military Systems of England, France, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Sardinia. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1861.

- European Cavalry, Including Details of the Organization of the Cavalry Service Among the Principal Nations of Europe. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1861.

- Exploration of the Red River of Louisiana in the Year 1852 (with Randolph B. Marcy). Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson, 1854.

- Regulations and Instructions for the Field Service of the United States Cavalry in Time of War, 1861. Reissued as Regulations and Instructions for the Field Service of the U.S. Cavalry in Time of War. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1862.

- McClellan's Own Story: The War for the Union, The Soldiers Who Fought It, The Civilians Who Directed It and His Relations to It and to Them (William C. Prime, Editor). New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887.

- The Life, Campaigns, and Public Services of General George B McClellan. Philadelphia: T.B. Peterson & Brothers, 1864.

- The Democratic Platform, General McClellan's Letter of Acceptance. New York: Democratic National Committee, 1864.

- The Army of the Potomac, General McClellan's Report of Its Operations While Under His Command. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1864.

- Report of Major General George B McClellan, Upon the Organization of the Army of the Potomac and Its campaigns in Virginia and Maryland. Boston: Boston Courier, 1864.

- Letter of the Secretary of War by George Brinton McClellan. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864.

- West Point Battle Monument, History of the Project to the Dedication of the Site (Oration of Major-General McClellan). New York: Sheldon & Co., 1864.

See also

In Spanish: George Brinton McClellan para niños

In Spanish: George Brinton McClellan para niños

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- Conservative Democrat