University of Oxford Botanic Garden facts for kids

Quick facts for kids University of Oxford Botanic Garden & Harcourt Arboretum |

|

|---|---|

View outside the Walled Garden with Magdalen Tower in the background

|

|

| Type | Botanic Garden |

| Location | High Street, Oxford, England |

| Area | 1.8 hectares (18,000 m2) |

| Created | 1621 |

| Operated by | University of Oxford |

| Visitors | 211,573 (2019) |

| Status | Open all year |

| Website | https://www.obga.ox.ac.uk |

The University of Oxford Botanic Garden is the oldest botanic garden in Great Britain. It is also one of the oldest science gardens in the world. The garden started in 1621 as a special garden for growing plants used in medicine.

Today, it has more than 5,000 different types of plants. These plants cover about 1.8 hectares (4.5 acres). It is one of the most varied plant collections in a small space anywhere. It includes plants from over 90% of all the main plant families.

Simon Hiscock became the head of the garden in 2015. Before him, Timothy Walker led the garden from 1988 to 2014.

Contents

History of the Garden

How the Garden Started

In 1621, a man named Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby gave a lot of money (about £5 million today). He wanted to create a garden for plants used in medicine. His goal was "to show off God's creations and help people learn."

He chose a spot next to the River Cherwell. This land was at the northeast corner of Christ Church Meadow. It belonged to Magdalen College. Part of the land used to be a Jewish cemetery. This was until Jewish people were asked to leave Oxford in 1290.

Workers had to bring in 4,000 cartloads of "muck and dung." This was to raise the land above the flood plain of the River Cherwell.

Plant Catalogues

Humphry Sibthorp started making a list of the garden's plants. This list was called Catalogus Plantarum Horti Botanici Oxoniensis. His youngest son, John Sibthorp, who was also a botanist, continued this important work.

What You Can See: Garden Layout

The Botanic Garden has three main parts:

- The Walled Garden, which has the original stone walls from the 1600s. It is home to the garden's oldest tree, an English yew.

- The Glasshouses, which are special buildings. They protect plants that need warm or special conditions from the British weather.

- The area between the Walled Garden and the River Cherwell.

There is also another site called the Harcourt Arboretum. It is about 6 miles (10 km) south of Oxford.

The Danby Gateway: A Grand Entrance

The Danby gateway is one of the main entrances to the Botanic Garden. Nicholas Stone designed it between 1632 and 1633. It is one of the first buildings in Oxford to use a classical, early Baroque style. This style was quite new for the time.

The gateway has three sections, each with a triangular top called a pediment. The middle section is set back. Its larger pediment is partly hidden by the smaller ones on the sides.

The stone is highly decorated. It has rough, bumpy stone mixed with smooth, flat stone. The side pediments look like they are held up by round columns. These columns frame spaces with statues of Charles I and Charles II. The middle pediment has a bust (head and shoulders statue) of the Earl of Danby. This gate is a Grade I listed building, meaning it's very important. It was even shot at during the English Civil War.

The Walled Garden: A Special Place

Botanical Family Beds

The main collection of tough plants in the Walled Garden is set up in long, narrow beds. Plants are grouped by their plant family. They are arranged using a system created by 19th-century botanists, Bentham and Hooker.

Many plant families are shown here. These include: Acanthaceae, Amaranthaceae, Amaryllidaceae, Apocynaceae, Araceae, Aristolochiaceae, Berberidaceae, Boraginaceae, Campanulaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Cistaceae, Commelinaceae, Compositae, Convolvulaceae, Crassulaceae, Cruciferae, Cyperaceae, Dioscoreaceae, Dipsacaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Gentianaceae, Geraniaceae, Gramineae, Hypericaceae, Iridaceae, Juncaceae, Labiatae, Leguminosae, Liliaceae, Linaceae, Loasaceae, Lythraceae, Malvaceae, Onagraceae, Paeoniaceae, Papaveraceae, Phytolaccaceae, Plantaginaceae, Plumbaginaceae, Polemoniaceae, Polygonaceae, Portulacaceae, Primulaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Rubiaceae, Rutaceae, Saxifragaceae, Solanaceae, Umbelliferae, Urticaceae, Verbenaceae, Violaceae.

In 1983, the NCCPG chose Oxford Botanic Garden to grow the national collection of euphorbia plants. One of the rarest plants here is Euphorbia stygiana. Only ten of these plants are left in the wild. The Garden is growing more of them quickly to help save them from disappearing.

Medicinal Plant Beds

In the southwest part of the Botanic Garden, there is a modern collection of medicinal plants. Here, you will find eight beds. Each bed grows plants linked to medicines for a certain type of sickness. There are beds for:

- Heart problems (Cardiology)

- Cancer (Oncology)

- Infections (Infectious Diseases)

- Stomach and digestion issues (Gastroenterology)

- Skin problems (Dermatology)

- Blood disorders (Haematology)

- Nervous system and pain relief (Neurology)

- Lung and breathing problems (Pulmonology)

The plants in these beds have many natural chemicals. They can be used in three ways:

- Directly as a medicine.

- Changed slightly to make a useful medicine.

- As a starting point to discover new medicines.

Bearded Irises

One bed in the northwest corner of the garden shows off bearded irises every May. You can see types like Iris 'Eileen' and Iris 'Golden Encore'. Some of the varieties grown here are not found anywhere else.

Wall Borders: Microclimates

The areas along the bottom of the walls have special plant collections. These plants grow well in the unique microclimate (small, local climate) there. Many of these plants are grouped by where they come from in the world.

The Mediterranean collection is along the north wall. It includes Euphorbia myrsinites. The South American collection, also at the north border, has Feijoa sellowiana. The South African collection at the northeast border includes Kniphofia caulescens.

Other wall borders have plants from Biodiversity hotspots. These are areas like Japan and New Zealand. Hotspots have many unique plant species. However, their natural plant life is greatly threatened. Over half of the world's plant species live in these hotspots. Yet, these areas cover only 2.3% of Earth's land.

Glasshouses: Plants from Around the World

The Conservatory

This building is a metal copy of the old wooden one from 1893. It grows seasonal flowers like primulas, abutilons, fuchsias, and achimenes. Different plant displays are shown in the middle area throughout the year.

Alpine House

Plants that cannot grow well outside in the British weather are shown in this house. The displays are changed often so there is always something in bloom.

Fernery

This house has a collection of ferns from all over the world. You can see Platycerium bifurcatum (a stag's horn fern). There is also Lygodium japonicum (a climbing fern) and Trichomanes speciosum (a filmy fern from western Britain).

Tropical Lily House

The large tank in the lily house was built in 1851. Professor Charles Daubeny, who was in charge of the Garden then, built it. It is the oldest part of the glasshouses still standing. Tropical water lilies grow in boxes in the tank. This includes the Nymphaea × daubenyana lily, named after Professor Daubeny.

Other useful plants grow here too. These include bananas, sugar cane, and rice. The papyrus reed, Cyperus papyrus, also grows here. It comes from river banks in the Middle East. High up in the glasshouse, you can see the yellow flowers of Allamanda cathartica.

Insectivorous House: Carnivorous Plants

This house has a collection of Carnivorous plants. These plants have developed many ways to catch insect prey. Some traps are simple, like the sticky leaves of Pinguicula plants. Others, like the Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula, actually move. They snap shut when an insect walks on them.

Palm House: Tropical Giants

This is the biggest glasshouse in the Garden. It grows palms and many plants that are important for food or other products. These include citrus fruits, pepper, sweet potato, pawpaw, olives, coffee, ginger, coconuts, cocoa, cotton, and oil palms.

There is also a collection of cycads. These plants look like palms but are not related. Important teaching collections here include the Acanthaceae, like the shrimp plant Justicia brandegeana. You can also find Gesneriaceae and many Begonia species.

Arid House: Desert Survivors

Plants in this house come from dry areas of the world. They show how plants save water. Many different types of cacti and Succulent plants are here. They use various ways to reduce water loss in their harsh homes.

Outside the Walled Garden: Diverse Plantings

Rock Garden

This area features plants that grow well in rocky, mountain-like conditions.

Bog Garden

Here, you will find plants that thrive in wet, marshy soil.

Herbaceous Border

This planting was first created in 1946. It is a classic example of a traditional English herbaceous border. Unlike other parts of the Garden, this border only uses herbaceous perennials. These plants die back to their roots each winter. Then, they grow back in spring and flower all summer. The design aims to be interesting from April to October. It starts with colorful tulips. Then, early, mid-season, and late-flowering perennials appear. The plants are arranged in layers, with shorter ones at the front and taller ones at the back.

Autumn Border

This border is designed to look beautiful in the autumn months.

Glasshouse Borders

These plantings are found around the glasshouses.

Merton Borders

These borders were designed with Professor James Hitchmough. He is from the University of Sheffield. At 955 square meters, these are the largest planted area in the Botanic Garden. They show how to grow plants in a way that is good for the environment.

The plants here were chosen because they can handle dry conditions. They come from naturally dry grasslands in three parts of the world:

- The central and southern Great Plains of the USA, extending to California.

- East South Africa, in areas above 1000 meters.

- Southern Europe to Turkey and across Asia to Siberia.

The Garden in Famous Books

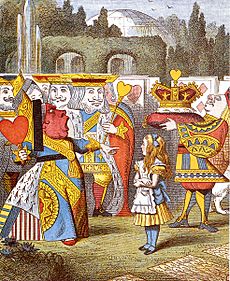

The Garden was often visited in the 1860s by Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. He was an Oxford math professor, also known as Lewis Carroll. He came with the Liddell children, including Alice Liddell. Like many places and people in Oxford, the Garden inspired Carroll's stories in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The Garden's waterlily house can be seen in the background of an illustration for "The Queen's Croquet-Ground."

Another Oxford professor and author, J. R. R. Tolkien, often spent time in the garden. He liked to relax under his favorite tree, a Pinus nigra. This huge Austrian pine reminded him of the Ents in his The Lord of the Rings story. Ents are walking, talking tree-people from Middle-earth. Sadly, the tree was removed in 2014. Two of its large branches fell, making it unsafe for visitors.

In the book Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh, Lord Sebastian Flyte takes Charles Ryder "to see the ivy." Sebastian says, "Oh, Charles, what a lot you have to learn! There's a beautiful arch there and more different kinds of ivy than I knew existed. I don't know where I should be without the Botanical gardens."

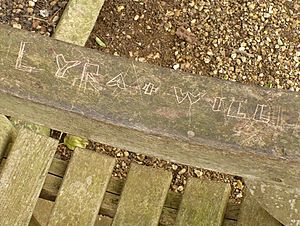

In Philip Pullman's books His Dark Materials, a bench in the back of the garden is very important. It is a place that exists in two different worlds. The main characters, Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry, promise to sit on this bench. They agree to do so for an hour at noon on Midsummer's Day every year. They hope to feel each other's presence in their own worlds. Now, fans of Pullman's books visit this bench. It often has carvings like "Lyra + Will" or "L + W." Since 2019, a sculpture by Julian Warren has been placed behind it.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Jardín botánico de la Universidad de Oxford para niños

In Spanish: Jardín botánico de la Universidad de Oxford para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |