Yavapai facts for kids

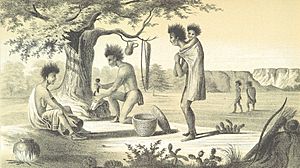

An early 20th-century Yavapai basket bowl woven of willow and reed

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,550 (1992) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (Arizona) | |

| Languages | |

| Yavapai (three dialects of Upland Yuman language), English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Havasupai, Hualapai, Mohave, Western Apache |

The Yavapai ( yav-Ə-py) are a Native American tribe living in Arizona. Their Yavapai language is part of the Upland Yuman language family. This family is thought to be a branch of the larger Hokan language family.

Today, Yavapai people are part of these official tribes:

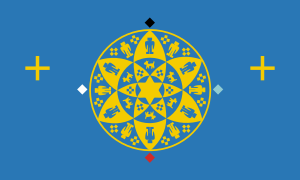

- Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation

- Yavapai-Apache Nation of the Camp Verde Indian Reservation

- Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe

The Yavapai once controlled about 10 million acres of land in west-central Arizona. Their lands stretched from the San Francisco Peaks in the north to the Pinaleno Mountains and Mazatzal Mountains in the southeast. They reached the Colorado River in the west and almost to the Gila River and Salt River in the south.

Historically, the Yavapai were split into four main groups or bands:

- Kewevkepaya (southeastern)

- Tolkepaya (western)

- Wipukepa (northeastern), also called the Verde Valley Yavapai

- Yavepé (northwestern)

Contents

Understanding the Yavapai Name

The name Yavapai comes from the Mojave language. It means "People of the Sun."

Early American settlers sometimes called the Yavapai by other names. These included "Mohave-Apache," "Yuma-Apache," or "Tonto-Apache."

Exploring the Yavapai Language

The Yavapai language is one of three dialects of the Upland Yuman language. This language is part of the Pai branch of the Yuman language family. The Upland Yuman language might also be part of the larger Hokan language family.

The Yavapai language has three main dialects. These are Kwevkepaya (Southern), Tolkepaya (Western), Wipukepa (Verde Valley), and Yavepe (Prescott).

Yavapai Population Numbers

In 1992, the Yavapai population was about 1,550 people. Some experts believe there were around 1,500 Yavapai in the year 1500.

A Look at Yavapai History

The Yavapai creation story says their people came from a tree or maize plant. This plant grew from the ground at what is now Montezuma Well.

Experts believe the Yavapai came from Patayan (Hakataya) peoples. These groups moved east from the Colorado River area. They became the Upland Yumans. Evidence suggests they became the Yavapai around 1300 CE.

Early European Contact (16th Century)

The first time Europeans met the Yavapai was in 1583. Hopi guides led Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo to Jerome Mountain. De Espejo was looking for gold but only found copper. In 1598, Hopi guides brought Marcos Farfán de los Godos to the same mines. Farfán called the Yavapai cruzados because they had crosses painted on their heads.

Life in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Juan de Oñate led other groups through Yavapai lands in 1598 and 1604–1605. They were searching for a route to the sea that Yavapai people had told them about.

Warfare was common for the Yavapai. They made changing alliances to stay safe. Wi:pukba (Wipukepa) and Guwevkabaya (Kwevkepaya) groups teamed up with Western Apache bands. They would attack and defend against raids from the Akimel O'odham and Maricopa from the south. Yavapai and Apache raids were usually small and quick. They would retreat to avoid counter-attacks. The Yavapai also defended their lands when the Akimel O'odham came to gather saguaro fruits.

To the north, Wi:pukba and Yavbe' groups had changing relationships with the Pai people. Both Pai and Yavapai spoke Upland Yuman dialects. They also shared a common culture. However, both groups have stories about a disagreement that separated them. Scholars think this split happened around 1750.

Over time, the Yavapai started to adopt some European ways. They learned about raising livestock and planting crops. They also began using metal tools and weapons. They even adopted some ideas from Christianity. About a quarter of the Yavapai population died from smallpox in the 17th and 18th centuries. This was a big loss that changed their societies. With guns and new weapons, their ways of fighting, talking with others, and trading also changed. They sometimes took livestock from other tribes or Spanish settlements to help their economy. They also sometimes exchanged people for European goods.

Spanish missionary Francisco Garcés lived among the Yavapai in 1776.

Changes in the 19th Century

In the 1820s, American beaver trappers entered Yavapai territory. They had already used up the beaver population in the Rocky Mountains.

The first fights between US troops and Yavapai happened in early 1837. The Tolkepaya joined their Quechan neighbors to defend a ferry crossing on the Colorado River. After some conflict, the US government took control of the crossing.

More Euro-American settlers passed through Yavapai land after gold was found in California in 1849. Despite this, the Yavapai tried to avoid contact with Americans.

A major battle between the Colorado–Gila River alliances happened in August 1857. About 100 Yavapai, Quechan, and Mohave warriors attacked a Maricopa settlement.

The Yavapai Wars, also called the Tonto Wars, were conflicts between the Yavapai and Tonto Apache against the United States. These began around 1861 when American settlers arrived on Yavapai and Tonto land. During this time, many Yavapai were killed or forced to move. Out of 1,400 remaining Yavapai, 366 to 489 were killed. Another 375 died during forced removals.

In 1863, gold was found in Lynx Creek near Prescott, Arizona. This led to many White settlements being built in Yavapai territory. These included towns along the Hassayampa and Agua Fria Rivers, Prescott, and Fort Whipple.

American forces, led by General George Crook, fought against the Yavapai and Tonto Apache in 1872–73.

The 20th Century and Beyond

By 1900, most Yavapai left the San Carlos Reservation. They returned to the Verde Valley and their homelands.

Yavapai Culture and Traditions

Traditional Foods

Before living on reservations, the Yavapai were mostly hunter-gatherers. They moved each year to find ripening plants and game animals. Some groups also grew small amounts of "three sisters" crops: maize, squash, and beans. The Tolkepaya, who lived in drier lands, relied more on farming. They often traded animal skins, baskets, and agave with Quechan groups for food.

Important plant foods included walnuts, saguaro fruits, juniper berries, acorns, and sunflower seeds. Manzanita berries and apples, hackberries, and the bulbs of the Quamash were also eaten. Agave was very important because it was available from late fall to early spring. The hearts of the agave plant were roasted and stored. Animals hunted included deer, rabbit, jackrabbit, quail, and woodrat. Most Yavapai groups did not eat fish or water birds.

Yavapai Dances and Songs

The Yavapai performed traditional dances. These included the Mountain Spirit Dance, War Dances, Victory Dances, and Social Dances. The Mountain Spirit dance was a masked dance used for guidance or healing. The masked dancers represented Mountain Spirits. These spirits live in Four Peaks, McDowell Mountains, Red Mountain, Mingus Mountain-(Black Hills), and Granite Mountain. They also live in the caves of Montezuma Castle and Montezuma Well.

Yavapai also take part in dances and singing shared with neighboring tribes. These include the Apache Sunrise Dance and the Bird Singing and Dancing of the Mojave people.

- The Sunrise Dance Ceremony may have come to the Yavapai from the Apache. Apache and Yavapai often married each other and shared parts of their cultures. Both tribes live together on the Camp Verde and Fort McDowell reservations. The Sunrise Dance is a four-day ceremony for young Apache girls. It usually happens from March to October. This ancient dance is special to the Apache. It is linked to Changing Woman, a powerful figure in Apache culture.

- Bird Singing and Dancing: This tradition started with the Mojave people of the Colorado River region. Modern Yavapai culture has adopted it. Bird singing and dancing tells a story. It takes an entire night to sing the whole cycle, from sunset to sunrise. This story tells how the Yuman people were created. Bird songs are sung with a gourd rattle. Today, bird singing and dancing is used for many reasons, like mourning, celebrating, and social gatherings.

Traditional Homes

The Yavapai built brush shelters called Wa'm bu nya:va. In summer, they made simple lean-tos without walls. In winter, they built closed huts called uwas. These were made of ocotillo branches or other wood. They were covered with animal skins, grasses, bark, or dirt. In the Colorado River area, Tolkepaya built rectangular huts. These huts had dirt piled against the sides for insulation and a flat roof. They also used caves or old pueblos for shelter from the cold.

How Yavapai Groups Organized Themselves

The main way Yavapai organized themselves was through local groups of extended families. These families lived in specific areas. These local groups would form larger bands during times of war or raids. For most of Yavapai history, the family was the most important group. This was partly because most places with food were not big enough for many people.

In winter, larger groups of several families would camp together. They would split into smaller groups at the end of winter for the spring harvest.

Yavapai government was informal. There were no tribal chiefs. Some men became leaders because others chose to follow their advice. Men known for their fighting skills were called mastava ("not afraid"). Other warriors would follow them into battle. Some Yavapai men were known for their wisdom and speaking ability. They were called bakwauu ("person who talks"). They would settle arguments and advise on camp locations or food gathering.

Yavapai Bands and Their Lands

The Yavapai were never ruled by one central government. Historically, they were four separate groups or bands. They were connected by family ties and shared culture and language. These four bands were the Kewevkepaya (southeastern), Tolkepaya (western), Wipukepa (northeastern), and Yavepé (northwestern).

The Kewevkepaya lived in the southeast. Their lands were along the Verde River south of the Mazatzal Mountains and the Salt River. They also lived near the Superstition Mountains and the western Sierra Estrella Mountains. They married with the Tonto Apache and San Carlos Apache and spoke their languages too.

The Tolkepaya lived in western Yavapai territory. Their lands were along the Hassayampa River in southwestern Arizona. They had strong ties with the Quechan and Mojave.

The Wipukepa lived in the northeast. Their lands included Oak Creek Canyon and areas along Fossil Creek and Rio Verde, Arizona. They often married Tonto Apache people and spoke their language. Their name means "People from the Foot of the Red Rock."

The Yavapé lived in northwestern Yavapai territory. Their lands stretched from Williamson Valley south of the Bradshaw Mountains to the Agua Fria River. They were sometimes called the "real Yavapai" because they were less influenced by other groups.

There was also a fifth Yavapai band, the Mađqwarrpaa or "Desert People," but they no longer exist. The Yavapai share many things with their language relatives to the north, the Havasupai and the Hualapai.

Yavapai and Apache Connections

The Wi:pukba and Guwevkabaya Yavapai lived near the Tonto Apache. The Tonto Apache usually lived east of the Verde River, and most Yavapai bands lived west of it. However, their lands often overlapped.

Because they lived so close, they formed mixed groups. People in these groups often spoke both the Apache language and the Yavapai language. The leader of each group usually had two names, one from each culture. They also raided and fought together against enemy tribes like the Tohono O'odham and the Akimel O'odham.

Europeans often called both the Yavapai and Apache by the same names, like Tonto Apache. This makes it hard for scholars to know which group was being talked about in old records.

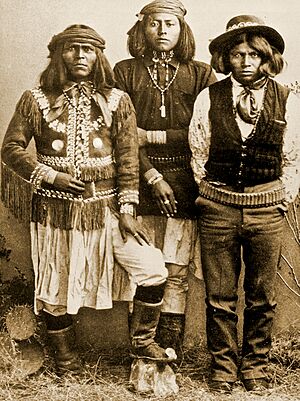

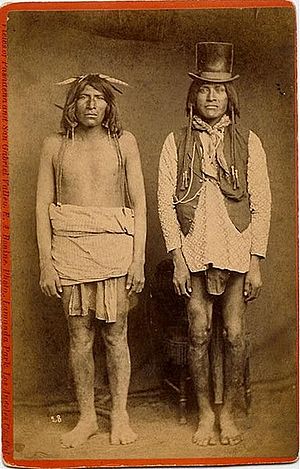

There were some physical differences between Yavapai and Tonto Apache. Yavapai were often described as taller and more muscular. Tonto Apache were usually smaller and less muscular. Yavapai often had tattoos, but Apache rarely did. They also had different funeral practices. Their moccasins were shaped differently too. Both groups were hunter-gatherers, and their campsites looked very similar.

Yavapai Tribes and Reservations

Yavapai–Apache Nation

After being moved to the Camp Verde Reservation near Camp Verde, the Yavapai built irrigation systems. These systems helped them grow enough food to be self-sufficient. However, some contractors who supplied the reservations were unhappy. They asked the government to close the reservation. In March 1875, the government closed it. The residents were forced to march 180 miles (290 km) to the San Carlos reservation. More than 100 Yavapai died during this difficult winter journey.

By the early 1900s, Yavapai began leaving San Carlos. They asked to return to the original Camp Verde Reservation. In 1910, 40 acres (161,874 m2) were set aside for the Camp Verde Indian Reservation. More land was added later. These two areas became the Camp Verde Yavapai–Apache tribe in 1937. Today, the reservation covers 665 acres (2.7 km2) in four separate places. Tourism is very important to the tribe's economy. This is because of many preserved sites, like the Montezuma Castle National Monument. The Yavapai–Apache Nation combines two tribes that lived in the Upper Verde area before Europeans arrived.

Yavapai Prescott Indian Reservation

The Yavapai reservation in Prescott was created in 1935. It started with 75 acres (300,000 m2) of land. In 1956, another 1,320 acres (5 km2) were added. After the first chief, Sam Jimulla, his wife Viola became the first female chief of a North American tribe. Today, the tribe has 159 official members. Most of the people are from the Yavbe'/Yavapé Group of Yavapais.

Fort McDowell Reservation

The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation is about 20 miles northeast of Phoenix. This reservation was created in 1903 by Theodore Roosevelt. It was 40 square miles (100 km2) in size. By 1910, the government tried to move the residents to open up the area for other uses. A group of Yavapai spoke to a Congressional Committee against this plan, and they won. Today, the tribe has 900 members. About 600 live on the reservation. The Guwevkabaya or Southeastern Yavapai on Fort McDowell Reservation call themselves A'ba:ja - "The People." Some experts believe the name Apache comes from this Yavapai self-name.

The Orme Dam Conflict

In the early 1970s, officials wanted to build a dam where the Verde and Salt rivers meet. This dam would have flooded two-thirds of the 24,000-acre (97 km2) reservation. The tribe members were offered homes and money. But in 1976, the tribe voted against the offer. They felt the move would break up their tribe. In 1981, after much effort and a three-day march by about 100 Yavapai, the plan to build the dam was stopped.

Famous Yavapai People

- Viola Jimulla (Prescott Yavapai, 1878–1966), chief of the Yavapai-Prescott Tribe from 1940 to 1966.

- Patricia Ann McGee (Yavapai/Hulapai, 1926–1994), chief of the Yavapai-Prescott Tribe.

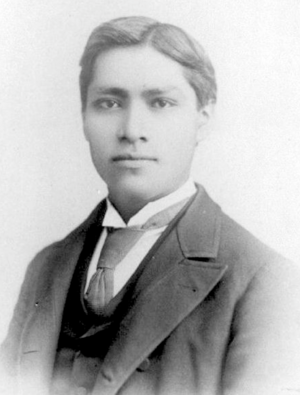

- Carlos Montezuma, Wassaja (Yavapai/Apache, c. 1866–1923), a doctor and activist for Indigenous rights. He helped start the Society of American Indians.

- Clinton Pattea (Yavapai, 1930–2013), president of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation. He supported Indian gaming.

- Y. B. Rowdy (Yavapai, c. 1862–1893), a U.S. Army scout and Medal of Honor recipient.

See Also

In Spanish: Yavapai para niños

In Spanish: Yavapai para niños