Assyria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Assyria

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2025 BC–609 BC | |||||||||||

|

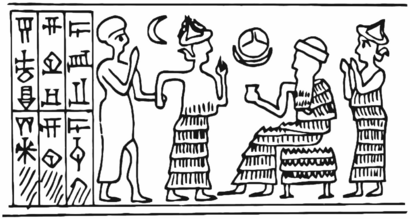

Symbol of Ashur, the ancient Assyrian national deity

|

|||||||||||

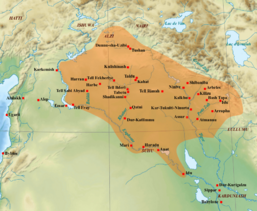

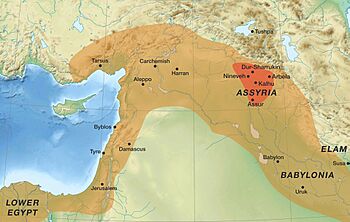

The ancient Assyrian heartland (red) and the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 7th century BC (orange)

|

|||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||

| Official languages | |||||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Notable kings | |||||||||||

|

• c. 2025 BC

|

Puzur-Ashur I (first) | ||||||||||

|

• c. 1974–1935 BC

|

Erishum I | ||||||||||

|

• c. 1808–1776 BC

|

Shamshi-Adad I | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age to Iron Age | ||||||||||

|

• Foundation of Assur

|

c. 2600 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Assur becomes an independent city-state

|

c. 2025 BC | ||||||||||

| c. 2025–1364 BC | |||||||||||

|

• Middle Assyrian period

|

c. 1363–912 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Neo-Assyrian period

|

911–609 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Conquest by the Neo-Babylonian and Median empires

|

609 BC | ||||||||||

|

• Sack and destruction of Assur by the Sasanian Empire

|

c. AD 240 | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Assyria was a powerful ancient civilization in Mesopotamia, a region in the Middle East. It started as a city-state around 2025 BC and grew into a large empire by the 14th century BC. The Assyrian Empire lasted until 609 BC.

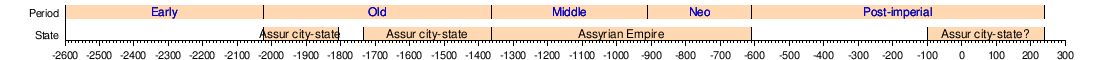

Historians divide Assyrian history into several periods. These include the Early Assyrian (around 2600–2025 BC), Old Assyrian (around 2025–1364 BC), Middle Assyrian (around 1363–912 BC), and Neo-Assyrian (911–609 BC) periods. The first capital city, Assur, was founded around 2600 BC. However, it became truly independent around 2025 BC.

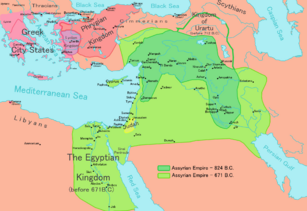

Assyria's power changed over time. It faced periods of foreign rule. But it rose to become a major kingdom, especially during the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods. At its peak, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had the strongest army in the world. It ruled the largest empire known at that time. This vast empire stretched from parts of modern-day Iran to Egypt.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in the late 7th century BC. It was conquered by a group of Babylonians and Medes. Even after the empire's fall, Assyrian culture and traditions continued for many centuries. The remaining Assyrian people in northern Mesopotamia gradually became Christianized starting in the 1st century AD. Their ancient religion continued in some places until the 3rd century AD and even later.

Ancient Assyria was successful because of its strong kings and smart ways of managing conquered lands. Its ideas about warfare and government influenced later empires. Assyria also left a rich cultural legacy. This legacy impacted later Assyrian, Greco-Roman, and Hebrew traditions.

Contents

Ancient Assyria: A Powerful Civilization

What Does "Assyria" Mean?

In the early days, when Assyria was just a city-state around the city of Assur, it was called ālu Aššur. This means "city of Ashur". Later, when it became a larger territory, it was known as māt Aššur, meaning "land of Ashur". Both names come from Ashur, the main god of Assyria. Ashur was likely seen as the city itself, made into a god.

The name "Assyria" that we use today comes from the Greek word Assuría. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus first used this term in the 5th century BC. Scholars believe that "Assyria" and "Syria" are connected. Both names likely came from the Akkadian word Aššur.

After the Assyrian Empire fell, other empires ruled the region. They often used names for the area that also came from Aššur. For example, the Achaemenid Empire called it Aθūrā.

A Look at Assyrian History

The Early Days of Assur

Villages in the Assyrian region existed as early as 6300–5800 BC. The city of Nineveh was inhabited even earlier. The first signs of the city of Assur itself date back to around 2600 BC. At first, Assur was likely not independent. It was controlled by stronger states from southern Mesopotamia.

Around 2025 BC, a kingdom called the Third Dynasty of Ur collapsed. This allowed Assur to become an independent city-state. Its first independent king was Puzur-Ashur I. During this time, Assur was a small city with fewer than 10,000 people. It did not have much military power.

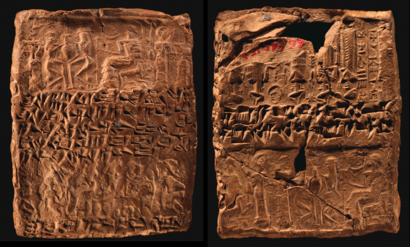

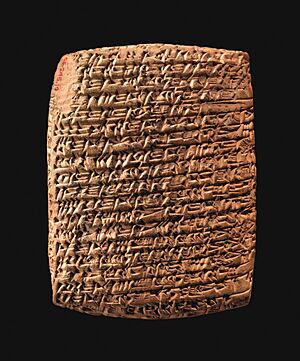

However, Assur became important for trade. Under King Erishum I, Assur tried out free trade. This meant people, not the government, managed most of the trading. This led to Assur becoming a major trading hub. Assyrian traders set up networks far away, even in what is now Turkey. Thousands of clay tablets from these trading posts tell us a lot about their business.

As conflicts grew in the Near East, trade became harder. Assur was often threatened by larger kingdoms. Around 1808 BC, an Amorite ruler named Shamshi-Adad I conquered Assur. He created a large kingdom in northern Mesopotamia. But this kingdom fell apart soon after his death around 1776 BC.

After this, Assur became independent again. But it faced struggles for power. Eventually, Bel-bani became king around 1700 BC. He started the Adaside dynasty, which ruled Assyria for about a thousand years.

The Rise of the Assyrian Empire

Assyria grew stronger thanks to two invasions by the Hittites. These invasions weakened other powerful kingdoms in Mesopotamia. This allowed Assyria to free itself from foreign control. Around 1363 BC, King Ashur-uballit I led Assyria to full independence. This marked the beginning of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Ashur-uballit I was the first Assyrian ruler to call himself "king." He even claimed to be as important as the Egyptian pharaohs. Under strong warrior-kings like Adad-nirari I, Shalmaneser I, and Tukulti-Ninurta I, Assyria expanded its territory. Shalmaneser I added the last parts of the Mitanni kingdom to Assyria. Tukulti-Ninurta I was especially successful. He won a major battle against the Hittites and even conquered Babylonia for a time. He also tried to move the capital from Assur to a new city, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.

After Tukulti-Ninurta I's death around 1207 BC, Assyria faced internal struggles. Its power decreased, and it became smaller. This period of decline was part of a larger crisis in the ancient world. However, some kings, like Tiglath-Pileser I, tried to regain lost lands. But their victories were often short-lived.

Around 934 BC, King Ashur-dan II began to reverse this decline. His efforts paved the way for the powerful Neo-Assyrian Empire, which started in 911 BC.

The Empire's Decline and Later Times

The early Neo-Assyrian kings worked hard to reclaim former Assyrian lands. This was a huge achievement. Under Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC), Assyria became the strongest power in the Near East. He marched his army to the Mediterranean Sea, collecting tribute from many kingdoms. Ashurnasirpal II also moved the capital to Nimrud in 879 BC. Assur remained an important religious center.

His son, Shalmaneser III, continued to expand the empire. Later, Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC) made the empire even stronger and larger. He conquered lands all the way to the Egyptian border and took control of Babylonia.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire reached its greatest size and power under the Sargonid dynasty. King Sargon II (722–705 BC) and his son Sennacherib (705–681 BC) expanded and strengthened the empire further. They also built new capitals. Sargon II built Dur-Sharrukin, and Sennacherib moved the capital to Nineveh. Sennacherib made Nineveh a grand city, possibly even building the famous Hanging Gardens there. Under Esarhaddon (681–669 BC), Assyria conquered Egypt, reaching its largest size ever.

After King Ashurbanipal (669–631 BC) died, the Neo-Assyrian Empire quickly collapsed. One big problem was the constant revolts in Babylonia. In 626 BC, Babylon revolted under Nabopolassar. Then, the Medes invaded. This led to the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Assur was captured in 614 BC, and Nineveh fell in 612 BC. The last Assyrian ruler, Ashur-uballit II, tried to fight back from Harran, but he was defeated in 609 BC. This marked the end of ancient Assyria as a state.

Despite the empire's fall, Assyrian culture continued for centuries. The Assyrian heartland faced difficult times under the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Many former capital cities were almost empty. However, under later empires like the Seleucid Empire and Parthian Empire, Assyria began to recover. Cities were rebuilt, and the population grew.

Assur itself thrived under Parthian rule. Local rulers may have seen themselves as continuing the ancient royal line. The old Ashur temple was even restored. This period of recovery ended around 240 AD when the Sasanian Empire captured Assur. The city was damaged, and its people scattered.

Starting in the 1st century AD, many Assyrians became Christians. However, some people continued to follow the old Mesopotamian religion for centuries. Assyrians remained a significant part of the population in northern Mesopotamia. But they faced severe challenges and hardship in the 14th century. Later, under the Ottoman Empire, they lived mostly in peace.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Assyrians faced more difficult times. They suffered greatly, including a period of severe hardship and loss of life. Throughout the 20th century, Assyrians sought more control over their lands. More recently, attacks by terrorist groups have caused many Assyrians to live in other countries.

How Assyria Was Governed

The Role of the King

In the early Assur city-state, the government was like an oligarchy. This meant a small group of powerful families shared power. The king was important but not the only ruler. Kings were seen as helpers for the god Ashur. They led meetings of the city assembly, which was the main governing body. This assembly was probably made up of the city's most powerful merchant families.

The king was the chief leader and helped with legal matters. He was called iššiak Aššur, meaning "governor for Ashur." Ashur was considered the true king of the city. People called the king rubā’um ("great one"), showing he was respected.

Later, under Shamshi-Adad I, kingship became more powerful. He was the first ruler of Assur to use the title šarrum (king). He also called himself "king of the Universe." This more absolute style of kingship was similar to rulers in Babylonia. By the Middle Assyrian period, the city assembly's power had disappeared. Kings became absolute rulers, very different from the earlier kings.

As the empire grew, kings used many grand titles. Ashur-uballit I was the first to call himself "king of the land of Ashur." Kings like Tukulti-Ninurta I used titles like "king of Assyria and Karduniash" and "king of all peoples." These titles showed their power and achievements.

Assyrian kings believed they were chosen by Ashur to rule. They saw their empire as the part of the world managed by Ashur through them. They thought lands outside Assyria were chaotic and uncivilized. So, it was the king's duty to expand Ashur's realm. This meant bringing order to these "strange lands" through conquest.

Kings also had religious duties. They performed rituals for Ashur and other gods. They were also the highest judges in the empire. Kings were expected to ensure the well-being and success of Assyria. Many inscriptions called them "shepherds" of their people.

Important Cities and Capitals

Assur was the main administrative center for most of Assyria's history. This was because it was the original city-state and held great religious importance. Even when kings moved their main government to other cities, Assur remained a ceremonial and religious heart. Kings could move the capital because they were Ashur's representatives. Wherever the king lived, that was, in a way, the capital of Assyria.

The first time the capital moved was under Tukulti-Ninurta I around 1233 BC. He created a new city called Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta. He might have been inspired by Babylonian kings who also built new capitals. However, after his death, the capital returned to Assur.

During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the capital moved several times. Ashurnasirpal II moved it to Nimrud in 879 BC. These new capitals were designed to show off royal power. Their palaces were larger than their temples, unlike in Assur.

In 706 BC, Sargon II built and moved the capital to Dur-Sharrukin. This move was likely a statement of his power. After Sargon II's death, his son Sennacherib moved the capital to Nineveh. Nineveh was a more natural center of power. After Nineveh fell in 612 BC, Ashur-uballit II made Harran his last seat of power. Harran was an important religious center.

Leaders and Officials

Assyrian society had important families who held top government jobs. These families were likely descendants of the most powerful people from the Old Assyrian period. One very important job was the vizier, a high-ranking official. There were also "grand viziers" who sometimes governed their own lands. In the Middle Assyrian period, these positions were often passed down through families.

In the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the elite group expanded. It included "magnates," who held high offices, and "scholars," who advised the king. Magnates included the treasurer, palace herald, chief cupbearer, chief officer, chief judge, grand vizier, and commander-in-chief. Some of these were still royal family members.

These magnates also governed important provinces and controlled large parts of the army. They owned big estates that were free from taxes. Later in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, some trusted royal advisors, who were not from traditional elite families, became very powerful. This was because they were seen as loyal only to the king.

From the time of Erishum I, an official called a limmu was chosen each year. The year was named after this official. Kings were often the limmu in their first year of rule. In the Old Assyrian period, the limmu had real power. But this power faded by the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Running a Big Empire

Assyria's success came from its ability to manage conquered lands well. From the Middle Assyrian period onward, Assyrian territory was divided into provinces. Each province had a governor who kept order and managed the local economy. Governors collected goods and taxes, which were inspected by royal officials every year. This helped the central government keep track of resources.

Some regions were not provinces but were still under Assyrian rule. These were called vassal states. They could keep their local kings if they paid tribute to Assyria. Assyrian kings also used a system to grant land to people in exchange for goods and military service.

To manage its vast empire, the Neo-Assyrian Empire created a clever communication system. It used relay stations to send messages quickly. An official message could travel 700 kilometers in less than five days. This speed was amazing for its time. It was not surpassed in the Middle East until the telegraph in 1865.

The Mighty Assyrian Army

Most of the Assyrian army was made up of regular people called up for campaigns. But the Neo-Assyrian Empire also had a small, permanent army unit called the "king's unit." In the Middle Assyrian period, there were also professional troops, possibly archers and charioteers. These soldiers needed special training.

The Assyrian army changed over time. Chariots were widely used under Tiglath-Pileser I. They had two soldiers: an archer and a driver. Later, in the Neo-Assyrian period, cavalry (soldiers on horseback) became more common.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire made big military improvements. They used cavalry on a large scale and adopted iron for armor and weapons. They also developed new ways to attack walled cities. At its peak, the Neo-Assyrian army was the strongest in the world. It likely had hundreds of thousands of soldiers. The army was divided into units of about 1,000 soldiers, mostly infantry. Infantry had different types: light, medium, and heavy, with various weapons and armor. The army also used interpreters and guides, often foreigners, during campaigns.

People and Society in Assyria

Who Lived in Assyria?

Most people in ancient Assyria were farmers. They worked on land owned by their families. In the Old Assyrian period, society had two main groups: people who worked without pay (often called subrum) and free citizens (called awīlum or "sons of Ashur"). Among free citizens, there were "big" and "small" members of the city assembly.

Assyrian society became more complex. In the Middle Assyrian Empire, there were several groups among the lower classes. Free men could receive land for government duties. Below them were people who had given up their freedom to work for others. They received clothes and food. These people could regain their freedom if they found a replacement. Other groups included "village residents" and people recruited through a system called ilku.

This social structure continued into the Neo-Assyrian period. Below the upper classes were free citizens, semi-free workers, and people who worked without pay. Families could move up in society by serving the state well. Sometimes, one person's great work improved their family's status for generations. Large family groups, or "clans," formed tribes that lived together in villages.

People who worked without pay were common in ancient Near Eastern societies. In Assyria, there were two main types. Some were foreigners captured in war. Others were people who couldn't pay their debts. Sometimes, children were taken by authorities because of their parents' debts. Children born to women who worked without pay also became workers, unless other arrangements were made.

The number of people working without pay in Assyria was never a huge part of the population. The Akkadian word wardum was used for these workers. But it could also mean free servants, soldiers, or subjects of the king. Many wardum managed property or did administrative tasks. This suggests some were free servants, not workers in the usual sense.

Women in Assyrian Society

In the Old Assyrian period, men and women had similar rights. Women could learn to read and write, as shown by letters they wrote. They paid the same fines, inherited property, traded, owned houses and workers, made wills, and could divorce.

Marriage records show that a bride's dowry belonged to her. Her children inherited it after her death. While men and women had equal rights, they were raised differently. Girls learned household tasks, while boys learned trades and went on trade trips. Sometimes, the eldest daughter became a priestess. She could not marry but became financially independent.

Wives were expected to provide clothes and food for their husbands. Husbands could take a second wife in trading colonies if their first wife could not have children. But there were strict rules: the second wife could not return to Assur, and both wives had to have homes and food.

The status of women changed in the Middle Assyrian period. Laws were introduced that changed women's rights and how they were treated. These laws gave men the right to punish their wives. Some laws required certain married women to wear veils in public. Other women, like those who worked without pay, were not allowed to wear veils.

Not all laws were against women. Women whose husbands died or were captured in war received government support if they had no sons or relatives. There were also women who lived independently, not tied to a husband or family. While most were poor, some were successful. This shows that women could live independent lives, even with fewer rights.

During the Neo-Assyrian period, royal and upper-class women gained more influence. Women in the royal court sent and received letters. They were wealthy and could own land. The queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire are well-known. Under the Sargonid dynasty, queens even had their own military units and sometimes joined campaigns.

Influential women included Shammuramat, wife of Shamshi-Adad V. She might have been a regent for her son, Adad-nirari III, and participated in military campaigns. Another was Naqi'a, who influenced politics during the reigns of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal.

How the Economy Worked

In the Old Assyrian period, many people in Assur were involved in international trade. Records show many jobs related to trade, like porters, guides, and bankers. This trade was well-documented. It's estimated that between 1950–1836 BC, 25 tons of silver went to Assur. In return, about 100 tons of tin and 100,000 textiles went to Anatolia. Assyrians also sold livestock and other goods. Many goods came from far away, like textiles from southern Mesopotamia and tin from the Zagros Mountains.

After trade declined in the 19th century BC, the Assyrian economy became more state-controlled. In the Neo-Assyrian period, the government was the largest employer. It had control over agriculture, manufacturing, and minerals. The empire's wealth mostly benefited the elite. It flowed to the government to maintain the state. Even though the state owned most production, private businesses still existed. The government protected individual property rights.

What Made Someone Assyrian?

A distinct Assyrian identity likely formed early on. Old Assyrian documents show unique burial practices, foods, and clothing. They also suggest that people in Assur saw themselves as a distinct cultural group. This identity spread across northern Mesopotamia during the Middle Assyrian Empire. Later, Neo-Assyrian kings spoke of "liberating the Assyrian people" in their conquests.

Ancient Assyrians had an open idea of what it meant to be Assyrian. Modern ideas of ethnic background or citizenship were not as important. Assyrian art showed foreign enemies with different clothes and equipment, not different physical features. Enemies were seen as "barbaric" because of their behavior or lack of proper religious practices.

There were no strong ideas of ethnicity or race in ancient Assyria. What mattered was fulfilling duties, being loyal to the king, and being part of the empire. King Sargon II's account of building Dur-Sharrukin shows this. He brought people from many lands and taught them to "work properly and respect the gods and the king." This shows that new settlers were expected to become Assyrian.

The expansion of the empire and movement of people changed the Assyrian heartland. But there is no evidence that the original Assyrian people disappeared. New settlers likely became "Assyrian" after one or two generations.

Modern Assyrian people are generally accepted by scholars as descendants of the ancient Assyrians. Even though the ancient Akkadian language and cuneiform writing faded after 609 BC, Assyrian culture survived. The old Assyrian religion was practiced in Assur until the 3rd century AD and in other places for centuries more. It gradually gave way to Christianity.

People with ancient Mesopotamian names were found in Assur until 240 AD and in other places until the 13th century. Many foreign states ruled Assyria over thousands of years. But there is no evidence of large numbers of immigrants replacing the original population. Assyrians remained a significant part of the region's people until the 14th century.

In older Christian writings, Assyrians often called themselves ʾārāmāyā ("Aramean") or suryāyā. The term ʾāthorāyā ("Assyrian") was used less often for themselves. This might be because the Assyrians in the Bible were enemies of Israel. However, the terms "Assyria" and "Assyrian" were used for the ancient empire and the land around Nineveh.

The term suryāyā is believed to come from the Akkadian word assūrāyu ("Assyrian"). This word was sometimes shortened to sūrāyu. Medieval Armenian sources also connected these terms. They called the Aramaic-speaking Christians of Mesopotamia and Syria Asori.

Despite these different names, older Christian writings sometimes positively identified with the ancient Assyrians. Ancient Assyrian kings and stories appeared in local folklore. Some high-ranking people even claimed descent from ancient Assyrian royalty. In the late 19th century, Assyrians experienced a cultural "awakening." This led to a stronger connection to their ancient Assyrian heritage. Today, sūryōyō or sūrāyā are common self-names, usually translated as "Assyrian."

Assyrian Culture and Knowledge

The Languages of Assyria

The ancient Assyrians mainly spoke and wrote Assyrian. This was a Semitic language, related to modern Hebrew and Arabic. It was very similar to Babylonian, spoken in southern Mesopotamia. Modern scholars see Assyrian and Babylonian as dialects of the Akkadian language. But ancient writers thought they were separate languages.

Assyrian language changed over time. Scholars divide it into Old Assyrian (2000–1500 BC), Middle Assyrian (1500–1000 BC), and Neo-Assyrian (1000–500 BC). Old Assyrian texts used fewer and simpler cuneiform signs. This makes it easier for modern researchers to read.

In the Middle and Neo-Assyrian empires, other forms of Akkadian were also used. Assyrian was for letters and daily documents. But Standard Babylonian was used for important official documents, scholarly works, and literature. Assyrian elite culture was influenced by Babylonia. Assyrians respected Babylon's ancient culture, much like ancient Rome respected Greek civilization.

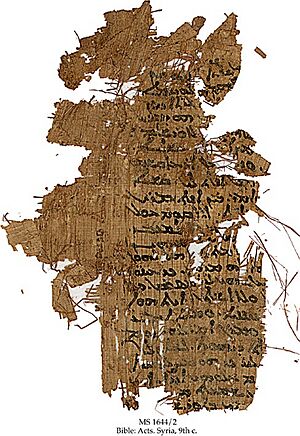

Because the empire was so large, many foreign words entered the Assyrian language. By the late reign of Ashurbanipal, fewer cuneiform documents were written. This suggests that Aramaic was becoming more common. Aramaic was often written on materials like leather scrolls, which do not last as long. The ancient Assyrian language disappeared around the end of the 6th century BC.

Aramaic and Other Languages

The Assyrians did not force their language on conquered peoples. This allowed other languages to spread. Aramaic became very important as Arameans moved into Assyrian territory. It was widely spoken and understood across the empire. Aramaic gradually replaced Neo-Assyrian, even in the Assyrian heartland. By the 9th century BC, Aramaic was the main common language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Neo-Assyrian became a language mostly for the political elite.

From the 9th century BC, Aramaic was used alongside Akkadian in official settings. Kings had scribes for both languages. This shows Aramaic became an official language. After the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell, the old Assyrian language was completely replaced by Aramaic. By 500 BC, Akkadian was probably no longer spoken.

Modern Assyrian people call their language "Assyrian" (Sūrayt or Sūreth). It is a modern form of ancient Mesopotamian Aramaic. It has some words from ancient Akkadian. Scholars often call modern Assyrian languages Neo-Aramaic or Neo-Syriac. Many Assyrians also use Syriac for religious services. This is a formal version of classical Aramaic.

Another language used for scholarship was ancient Sumerian language. At the height of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, many other local languages were spoken. But none became as officially recognized as Aramaic.

Amazing Assyrian Buildings

We learn about ancient Assyrian buildings from archaeological digs and old documents. Assyrian buildings were almost always made of mudbrick. Limestone was used for things like aqueducts and defensive walls.

Large buildings were often built on high platforms or mud brick foundations. Floors were usually made of packed earth. Important rooms had carpets or reed mats. Outdoor areas had stone or brick pavements. Wooden beams supported roofs, especially in big rooms.

The ancient Assyrians built complex projects, like entire new capital cities. This shows they had advanced technical skills. Assyrian architecture had unique features. These included stepped designs on walls, arched roofs, and palaces with many self-contained rooms.

Art and Creativity

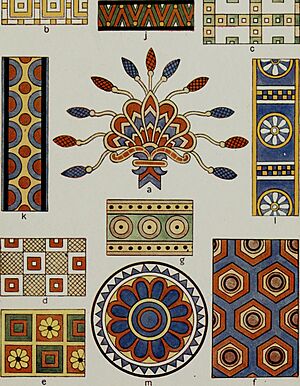

Many statues and figures from the Early Assyrian period were found in Assur temples. Much of this early art was influenced by foreign styles. For example, alabaster figures of worshippers from Assur look like Sumerian figures. Early Assyrian art varied greatly, from very stylized to very realistic.

A unique find is a woman's head with inlaid eyes and eyebrows. This piece shows the naturalistic style of the Akkadian period. Another special item is an ivory figurine of a woman. The ivory might have come from Indian elephants, suggesting early trade with Iran. Other early artworks include large stone statues of rulers and animals.

Art from the Old Assyrian period is mostly found on seals and seal impressions. Royal seals from the Puzur-Ashur dynasty were similar to those of the Third Dynasty of Ur. In the Middle Assyrian period, seals changed. They began to show royal power more than religious ideas. Non-royal seals had many designs, including religious scenes and peaceful images of animals and trees. Later, seals sometimes showed fights between humans, animals, and mythical creatures.

The Middle Assyrian period also saw new art forms. Four decorated altars were found in the Ishtar temple in Assur. These altars showed the king and protective figures. One relief on an altar is the earliest known story-telling image in Assyrian art. It shows prisoners before the king.

The first Assyrian wall paintings are from King Tukulti-Ninurta I's palace. They featured plant patterns, trees, and bird-headed spirits. Colors included black, red, blue, and white. A unique limestone statue of a woman was found in Nineveh. In the 11th century BC, obelisks became a new type of monument. These were four-sided stone pillars with images and text.

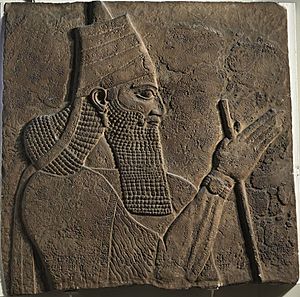

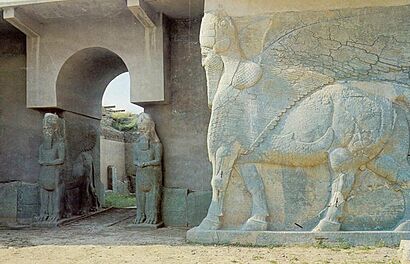

More art survives from the Neo-Assyrian period, especially large art made for kings. Famous examples are wall reliefs, carved stone art that decorated palace and temple walls. Another well-known art form is the colossi, giant human-headed lions or bulls called lamassu. These guarded gates of temples, palaces, and cities. The earliest examples of these are from King Ashurnasirpal II's reign. He may have been inspired by Hittite art.

Wall paintings also continued to be used. Interior walls were painted with mud plaster. Exterior walls sometimes had glazed and painted tiles. King Sennacherib's reign produced many wall reliefs. Scholars especially admire the reliefs from King Ashurbanipal's time. They are known for their "epic quality."

-

A wall relief likely showing Ashur, 21st–16th century BC.

-

Temple altar of Tukulti-Ninurta I, 13th century BC.

-

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, 9th century BC.

-

A statue of Shalmaneser III, 9th century BC.

-

An ivory head from the 8th–7th century BC. The ivory likely came from African elephants. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Books and Learning

Ancient Assyrian literature was greatly influenced by Babylonian stories. Not many literary texts survive from the Old and Middle Assyrian periods. A key Old Assyrian work is Sargon, Lord of Lies. This story tells about the reign of Sargon of Akkad, the founder of the Akkadian Empire.

A distinct Assyrian scholarly tradition began around the Middle Assyrian period. Kings started to see knowledge as a way to strengthen their power. Middle Assyrian works include the Tukulti-Ninurta Epic, other royal stories, and poems.

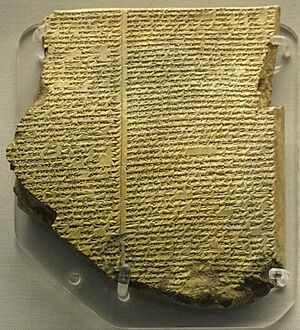

Most surviving ancient Assyrian literature is from the Neo-Assyrian period. Kings like Ashurbanipal believed it was their duty to preserve knowledge. The Library of Ashurbanipal had over 30,000 documents. Libraries were built to save past knowledge and scribal culture. Neo-Assyrian texts covered many topics. These included predictions, medical treatments, rituals, prayers, and school texts.

A new type of text in the Neo-Assyrian period was the annals. These recorded a king's reign, especially military victories. Annals were spread throughout the empire to support the king's rule.

Many literary works are known from this period. These include the Underworld Vision of an Assyrian Crown Prince and the Sin of Sargon. Assyrians also copied and saved older Mesopotamian literature. Texts like the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Enûma Eliš (the Babylonian creation myth) survived because of the Library of Ashurbanipal.

Religion in Ancient Assyria

Worshipping Ancient Gods

The ancient Assyrians believed in many gods, a system called polytheism. Their religion is sometimes called "Ashurism." They worshipped the same gods as the Babylonians. The most important Assyrian god was Ashur, who was also the name of their capital city. In early times, the god Ashur might have been seen as the city itself, made into a god.

Below Ashur, other Mesopotamian gods had specific roles. For example, the sun-god Shamash was a god of justice. Ishtar was a goddess of love and war. Each god had main places of worship. Babylonian gods like Enlil and Marduk were also worshipped in Assyria. Assyrians even adopted some Babylonian rituals, like the akitu festival.

Ashur's role changed over time. In the Old Assyrian period, he was a god of death and new life, linked to farming. In the Middle and Neo-Assyrian Empires, Ashur became a god of war. He gave kings divine power and commanded them to expand Assyria through military conquest. This idea might have come from a time when Assyria was under the control of the Mittani kingdom. Ashur was also called "king of the gods," a title previously given to Enlil.

Assyrian religion centered around temples. These large buildings had a main shrine for the god's statue and smaller chapels for other gods. Temples had their own resources, like land, and their own staff. Later, temples relied more on royal gifts and taxes. The head of a temple was responsible to the Assyrian king. Records show that predicting the future through astrology and studying animal insides was important. People believed gods communicated through these methods.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire did not force its religion on conquered lands. Few temples for Ashur were built outside northern Mesopotamia. After the empire fell, Assyrians continued to worship Ashur and other gods. But religious beliefs changed in different areas. Under Seleucid rule, Greek gods influenced Mesopotamian deities. There was also some influence from Judaism.

By the 1st century BC, Assyria was a diverse religious region. Under Parthian rule, both old and new gods were worshipped in Assur. Ashur remained the most important god until the city's capture in the 3rd century AD. His worship continued in the same way as it had 800 years earlier. The ancient Mesopotamian religion lasted in some places for centuries more, even until the 18th century in Mardin.

The Spread of Christianity

The Church of the East developed early in Christian history. We don't know exactly when Assyrians first became Christians. Tradition says Thomas the Apostle brought Christianity to Mesopotamia. The city of Arbela was an important early Christian center. Some traditions say Christianity took hold when Saint Thaddeus of Edessa converted King Abgar V in the 1st century AD. By the 3rd century AD, Christianity was clearly the main religion in the region.

Early Christian scholars often called themselves Arameans. This was because Aramaic was central to their language and culture. However, they also knew about their Assyrian heritage. This heritage came from biblical and cultural traditions. Syriac Christians saw themselves as Arameans due to their language and shared customs. This is similar to how Arabic speakers today might identify as Arabs.

For example, Ephrem the Syrian (around 306–373 CE) was an important Syriac Christian writer. He often criticized ancient Assyrians for their imperial violence. This reflected a common Christian view of pre-Christian empires. His writings showed a broad awareness of the region's history. This history was reinterpreted through a Christian viewpoint. So, Syriac Christians had a dual identity: Aramean in language and Assyrian in heritage.

It is likely that some Syriac Christians identified as "Assuraye" (Assyrians) before "Suryoyo" became common. Their Assyrian identity showed the lasting impact of the Assyrian Empire. The term "Suryoyo" came from the Greek word Syrios. It was adopted by Syriac Christians to show their language and religious identity. Both Arameans and Assyrians used this term. Over time, it became a shared religious and cultural identity.

Today, Christianity is a key part of Assyrian identity. But Assyrian Christians have divided into different Christian denominations. The main church is the Assyrian Church of the East. Other important churches include the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, and the Syriac Catholic Church. There are also Assyrians who follow different types of Protestantism.

These churches have been separate for centuries. But they share many of the same religious practices and beliefs. Efforts have been made to bring them closer together. In 1994, Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Dinkha IV signed an agreement. This was a step towards unity between the Catholic Church and the Assyrian Church of the East.

A historical challenge to unity was the ancient text Liturgy of Addai and Mari. This text, used in Assyrian churches, did not include certain words seen as essential by the Catholic Church. In 2001, the Catholic Church decided this text could still be considered valid. Efforts have also been made to reunite the Assyrian and Chaldean churches. In 1996, Dinkha IV and Patriarch Raphael I Bidawid signed proposals for unity.

See Also

In Spanish: Asiria para niños

In Spanish: Asiria para niños

- Beth Nahrain

- Beth Garmai

- Assyrian nationalism

- List of Assyrian settlements

- List of Assyrian tribes

- Assyrian cuisine