Catholic Church in England and Wales facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Catholic Church in England and Wales |

|

|---|---|

Westminster Cathedral, the mother church for Catholics in England

|

|

| Classification | Catholic |

| Orientation | Latin |

| Scripture | Bible |

| Theology | Catholic theology |

| Polity | Episcopal |

| Governance | CBCEW |

| Pope | Francis |

| President | Vincent Cardinal Nichols |

| Apostolic Nuncio | Miguel Maury Buendía |

| Region | England and Wales |

| Language | English, Welsh, Latin |

| Headquarters | London, England |

| Founder | Augustine of Canterbury |

| Origin | c. 200s: Christianity in Roman Britain c. 500s: Anglo-Saxon Christianity Britain, Roman Empire |

| Separations | Church of England (1534/1559) |

| Members | 5.2 million (baptised, 2009) |

The Catholic Church in England and Wales is part of the worldwide Catholic Church. It is connected to the Holy See (the Pope and his main offices in Rome). Its story began in the 6th century. Pope Gregory I sent a missionary named Augustine to England in 597 AD. Augustine, later known as Augustine of Canterbury, helped spread Christianity in the Kingdom of Kent. This linked the church in England to Rome.

This connection with the Pope lasted for many centuries. But in 1534, King Henry VIII ended it. Later, Queen Mary I brought the connection back in 1555. However, Elizabeth I finally broke it again in 1559. This led to a long period where Catholics faced many challenges.

For about 250 years, the government made it hard for Catholics to practice their faith openly. They were called recusants if they refused to attend Church of England services. Many had to practice their religion in secret. Some went to Catholic countries in Europe for education. Laws against Catholics continued into the 20th century. Open Catholic worship was banned until 1791.

In 2001, about 4.2 million Catholics lived in England and Wales. This was about 8% of the population. By 2009, this number grew to 5.2 million people. This increase was partly due to many people from Central Europe moving to England. Many of these new arrivals were Catholic. In North West England, about one in five people are Catholic. This is because many Irish people moved there in the 1800s. Also, many English Catholics lived in Lancashire during the difficult times.

Contents

- The Catholic Church in England and Wales: A Journey Through Time

- How the Catholic Church is Organized

- Images for kids

- See also

The Catholic Church in England and Wales: A Journey Through Time

How Christianity Began in Britain

Christianity first arrived in the British Isles a very long time ago. This was in the 1st or 2nd centuries. We know that British bishops attended important meetings in Europe. For example, Restitutus went to the Council of Arles in 314.

When the Romans left Britain, and Germanic groups invaded, contact with Europe decreased. But Christianity continued to thrive in the Brittonic parts of Great Britain. During this time, some unique practices developed. These are known as Celtic Christianity. But historians agree it was still part of the wider Western Christian Church.

In 597, Pope Gregory I sent Augustine of Canterbury and 40 missionaries. They came from Rome to teach the Anglo-Saxons about Christianity. This mission was very important for the Catholic Church. Augustine became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. He linked the new church directly to Rome.

The missionaries also brought the Rule of Benedict to English monasteries. This rule helped bring English churches closer to Europe and Rome. Popes often helped settle arguments and confirm kings. For example, Pope Leo IV confirmed Alfred the Great as king in 859.

Catholic Life in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, England and Wales were fully part of Western Christianity. Monasteries and convents were very important. They offered places to stay, hospitals, and education. Famous schools like Oxford and Cambridge were also important. Religious groups like the Dominicans and Franciscans had houses for students there.

Going on a Pilgrimage was a big part of Catholic life. England and Wales had many popular pilgrimage sites. Walsingham, Norfolk, became famous after a noblewoman had a vision of the Virgin Mary in 1061. She was asked to build a replica of the Holy House in Nazareth.

In 1170, Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was killed. He was quickly made a saint. This made Canterbury a major pilgrimage site. It even inspired Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Other shrines were at Holywell in Wales and Westminster Abbey.

An Englishman named Nicholas Breakspear became Pope Adrian IV (1154-1159). Later, Cardinal Stephen Langton became Archbishop of Canterbury. He played a key role in the dispute between King John and Pope Innocent III. This led to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215.

The Tudor Era: Big Changes for the Church

England was a Catholic country until 1534. That's when King Henry VIII officially separated from Rome. The Pope would not let Henry divorce his wife, Catherine of Aragon. So, Parliament said the King was the head of the Church in England. They also closed down monasteries and religious groups.

Henry himself did not change Catholic beliefs much. But he allowed some Protestant ideas to spread. People who refused to accept the King as head of the Church faced serious consequences. For example, Thomas More and John Fisher were executed. Protests against these changes, like the 'Pilgrimage of Grace', were put down.

From 1536 to 1541, Henry VIII closed down nearly 900 religious houses. These included monasteries, priories, convents, and friaries. He took their money and land. He sold these properties, mostly to pay for wars. This was a huge change for England. About one in fifty adult men were in religious orders at that time.

After Henry VIII, his young son King Edward VI ruled from 1547 to 1553. The Church of England became more Protestant. The Latin Mass was replaced by the English Book of Common Prayer. Statues and religious art in churches were destroyed. Many Catholic practices were stopped.

When Queen Mary I became queen in 1553, she brought Catholicism back. Many people, especially in rural areas, still held Catholic views. Mary wanted England to be fully Catholic again. However, her executions of about 300 Protestants were very unpopular. This earned her the nickname Bloody Mary.

When Elizabeth I became queen in 1558, England's religious situation was confusing. Elizabeth quickly reversed Mary's Catholic changes. The Act of Supremacy 1558 made it a crime to say the Pope had authority in England. People in public office had to swear loyalty to the Queen as head of the Church of England. Refusing to do so was a crime.

At first, Elizabeth was somewhat lenient with Catholics who kept their faith private. But in 1570, Pope Pius V said Elizabeth was not a rightful queen. He told Catholics to try and overthrow her. This made Catholics seem like traitors to many English people.

Laws against Catholics became much stricter. It became treason to become Catholic or to help someone become Catholic. Celebrating Mass was banned. Not attending Anglican services meant heavy fines. The "Act against Jesuits, Seminary priests and other such like disobedient persons" in 1585 made it treason for Catholic priests to even be in England. Many English Catholics were executed under this law.

Because of this persecution, Catholic priests were trained abroad. They went to colleges in Rome, Douai, and Spain. These places were in countries that were enemies of England. This made Catholics seem even more like traitors. By the end of Elizabeth's reign, England was clearly a Protestant country. Catholics were a minority, though still a significant part of the population.

The Stuart Era: Ups and Downs for Catholics

The reign of James I (1603–1625) brought some tolerance for Catholics. But this changed after the Gunpowder Plot. This was a plan by a small group of Catholics to kill the King and Parliament. Even so, James allowed some Catholics at court.

Under Charles I (1625–1649), Catholicism saw a small revival. His wife, Henrietta Maria, was Catholic. She had her own chapel and chaplain. This made Catholicism somewhat fashionable at court. Some anti-Catholic laws were not strictly enforced.

Religious tensions grew between Charles and Parliament. Parliament had many Puritans, who were strongly anti-Catholic. This was a major cause of the English Civil War. Almost all Catholics supported the King. When Parliament won, a strong anti-Catholic government took over.

When Charles II became king (1660–1685), his court also had Catholic influences. Charles himself leaned towards Catholicism. But he knew most English people were anti-Catholic. So, he agreed to laws like the Test Act. This law required public officials to deny Catholic beliefs.

Charles's brother, James, became Catholic in 1668–1669. When James became king in 1685, he was the first openly Catholic monarch since Mary I. He promised religious tolerance for all. But Protestants worried about a Catholic king. James put Catholics in important army positions. He also replaced Protestant leaders with Catholics.

The birth of a Catholic heir in 1688 caused even more fear. This led to the Glorious Revolution. Parliament decided James had left the throne. His Protestant daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III, became rulers. James fled into exile. The Act of Settlement 1701 still says that no Catholic can be monarch of England.

The 18th Century: A Quiet Time for Catholics

From 1688 to the early 1800s, Catholicism in England was at a low point. Catholics lost many rights. They couldn't own much property or inherit land easily. They paid special taxes. They couldn't send their children abroad for Catholic education. They couldn't vote. Priests could be imprisoned.

There were few Catholics in public life or the military. Many Catholic nobles left England or pretended to be Anglican. This meant fewer Catholic communities survived. A Catholic bishop during this time was called a Vicar apostolic. This was a special type of bishop who worked directly for the Pope.

Most Catholics lived quietly, away from the public eye. Alexander Pope, a famous poet, was a notable English Catholic of this time. He wrote the Iliad translation, which Samuel Johnson called the greatest ever. The Duke of Norfolk, a leading Catholic noble, also remained at court.

Later in the century, some laws against Catholics were relaxed. The Catholic Relief Act allowed Catholics to own property and join the army. But this led to the Gordon Riots in 1780. Protestant mobs attacked Catholic buildings in London. Still, reforms allowed priests to work more openly. This helped set up Catholic missions in towns.

The 19th Century: A Catholic Revival

A new beginning for Catholicism started in the 19th century. Thousands of French Catholics came to England during the French Revolution. England was seen as a safe place from the anti-Catholic violence in France. Also, in 1801, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was formed. This added many Irish Catholics to the new state.

Pressure grew to remove anti-Catholic laws. This was especially true because Catholic soldiers were needed for the Napoleonic Wars. In 1829, the Catholic Emancipation Act was passed. This gave Catholics almost equal civil rights. They could now vote and hold most public offices.

In the 1840s and 1850s, many Irish people moved to England and Scotland. This was especially true during the Great Irish Famine. They settled in cities like London, Liverpool, and Manchester. This greatly increased the number of Catholics in England.

At the same time, the Oxford Movement began within the Church of England. Some Anglicans wanted to bring back Catholic ideas and rituals. Many of them eventually converted to Catholicism. One famous convert was John Henry Newman in 1845. Many important thinkers and artists also became Catholic. These included writers like G. K. Chesterton and J. R. R. Tolkien, and the composer Edward Elgar.

Because of this growth, the Pope decided to bring back the Catholic hierarchy in England in 1850. He created 12 new Catholic dioceses. These were led by diocesan bishops, like in other Catholic countries. The new dioceses avoided using the same names as existing Church of England dioceses. This was to avoid conflict.

The 20th Century and Today

Catholicism in England continued to grow for much of the 20th century. It was linked to Irish immigrants and some English intellectuals. Many Catholics regularly attended Mass. The number of priests also grew.

However, later in the 20th century, fewer people became priests. Also, as Irish Catholics became more integrated into English society, some lost their distinct Catholic identity. The Second Vatican Council (Vatican II) brought changes to the Church. This led to some differences between traditional and more modern Catholic views.

Despite these changes, many people still join the Church. Public figures, including descendants of old Catholic families, openly share their faith. For example, former Prime Minister Tony Blair became Catholic in 2007.

Since Vatican II, the Church in England has focused on working with the Anglican Church. This is called ecumenism. They work together on many projects. For example, memorials have been put up for Catholic martyrs with Anglican support.

The Church also works for social justice. They help people facing poverty and homelessness. The Cardinal Hume Centre, for example, helps young homeless people. The Church also supports migrant workers.

New Groups for Anglicans

In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI offered a special way for Anglicans to join the Catholic Church. This was called Anglicanorum coetibus. It allowed them to keep some of their Anglican traditions and worship styles. By 2012, about 1200 people had joined this group, called the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham. This group helps show that the Catholic Church can have different ways of worship.

Diverse Catholic Communities

Many Cultures, One Faith

Many Catholics in England and Wales have come from other countries. In the 19th and 20th centuries, many Irish people arrived. More recently, many people from Eastern Europe have moved here. This has greatly increased the number of Catholics.

In 2008, about 74.6% of Catholics in the UK were White British. White Eastern Europeans made up 9.5%. White Irish were 4.4%. The Eastern European Catholics are mostly from Poland, but also from Lithuania, Latvia, and Slovakia.

Polish Catholic Immigration

Polish Catholics first came to England in the 1800s. After World War II, many Polish soldiers could not return home. Their country was under communist rule. So, about 250,000 Poles settled in Britain. Many joined existing Catholic churches.

The Polish Catholic Mission was set up to help them. It has many churches and centres across England and Wales. These places offer Mass and other services in Polish. This helps new arrivals feel at home and keep their faith.

Some Catholic leaders have encouraged Poles to join local English parishes. But the Polish Catholic Mission believes that integration is a long process. They work closely with the English Catholic leaders. Studies show that many Eastern European Catholics choose churches where Mass is offered in their native language.

How the Catholic Church is Organized

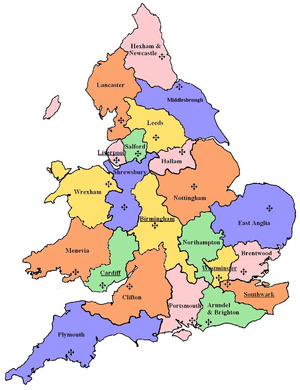

The Catholic Church in England and Wales is divided into five main areas called provinces. These are Birmingham, Cardiff, Liverpool, Southwark, and Westminster. These provinces contain 22 dioceses. Each diocese is then divided into smaller areas called parishes.

There are also special dioceses for specific groups. These include the Bishopric of the Forces for military personnel. There are also dioceses for Ukrainians and Syro-Malabar Catholics. The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham is for former Anglicans.

The Catholic bishops in England and Wales work together. They form the Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales. The Archbishop of Westminster, Vincent Gerard Nichols, leads this group. He is seen as the main leader for Catholics in England.

Historically, the Catholic Church in England avoided using the same names for its dioceses as the Church of England. This was to prevent conflict. But the Archdiocese of Westminster sees itself as continuing the line of the Archbishops of Canterbury from before the Reformation. They show this by listing all Catholic Archbishops of Canterbury and Westminster in one line.

Catholic Education and Youth Services

The Catholic Church runs a large network of schools in England and Wales. As of June 2024, there are over 2,100 Catholic nurseries, schools, colleges, and universities. The Church operates the largest group of academies in England.

Many dioceses also have special youth services. These teams help young people with their faith and personal development. They offer activities and support for Catholic youth.

Images for kids

-

Westminster Cathedral, the mother church for Catholics in England

-

Our Lady of Walsingham was a popular pilgrimage site.

-

Statue of Cardinal Newman outside the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, London.

-

Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, Liverpool.

-

Oratory Church of St Aloysius Gonzaga, Oxford, with the Vatican flag flying at half-mast after the death of Pope John Paul II.

-

A Ukrainian Greek Catholic parish church in Wolverhampton, England.

-

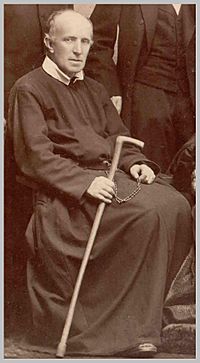

The Venerable Bernard Łubieński, a Polish Redemptorist missionary in Britain.

-

Blessed Frances Siedliska, founder of the Congregation of the Holy Family of Nazareth.

-

St Andrew Bobola Church, Hammersmith is regarded as the Polish "garrison" church.

See also

In Spanish: Iglesia católica en Inglaterra y Gales para niños

In Spanish: Iglesia católica en Inglaterra y Gales para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |