Clarence Thomas Supreme Court nomination facts for kids

In 1991, President George H. W. Bush chose Clarence Thomas to join the Supreme Court of the United States. This important court is the highest court in the country. Thomas was picked to replace Justice Thurgood Marshall, who was retiring. Marshall was a very important figure in civil rights and the first African American justice on the Supreme Court.

At the time, Clarence Thomas was a judge on a lower court called the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. President Bush had appointed him to that job just a year before. The process of approving Thomas for the Supreme Court was quite difficult and caused a lot of discussion. Many groups, including those supporting women's rights and civil rights, did not agree with Thomas's conservative views.

Despite the debates, the Senate voted on October 15, 1991. Clarence Thomas was approved by a close vote of 52 to 48. He officially became a Supreme Court Justice on October 23, 1991.

Contents

Choosing a New Justice

When Justice William Brennan retired from the Supreme Court in 1990, President Bush needed to choose someone new. Clarence Thomas was one of the top people President Bush considered. However, some of Bush's advisors felt Thomas wasn't quite ready because he had only been a judge for a short time. So, President Bush first nominated another judge, David Souter, who was easily approved.

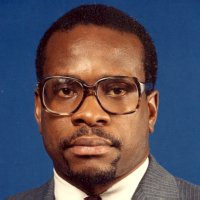

Later, when Justice Thurgood Marshall announced his retirement, President Bush again looked to Clarence Thomas. On July 1, 1991, President Bush nominated Thomas, who was 43 years old and an African American judge with conservative views. President Bush said Thomas was "the best person" to take Marshall's place. Some experts, however, felt that Thomas's experience was limited at the time.

First Hearings

Public hearings to discuss Thomas's nomination began on September 10, 1991. These hearings lasted for ten days. During this time, senators questioned Thomas and other people who spoke for or against his nomination. The senators mainly focused on Thomas's legal ideas. They asked about his past speeches, writings, and decisions he made as a judge.

For example, Senator Joe Biden, who led the Senate Judiciary Committee, asked Thomas about his views on property rights. Thomas was asked if he believed the Constitution gave individuals certain rights over their property, as discussed in a book called Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain. Thomas had to explain his thoughts on these complex legal topics.

Senate Votes

Committee Vote

After many discussions, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted on September 27, 1991. They decided to send Thomas's nomination to the full Senate without a specific recommendation. This meant they weren't saying "yes" or "no" to his approval. Earlier that day, a vote to recommend him positively had failed with a tie.

Full Senate Vote

The entire Senate voted on October 15, 1991. Clarence Thomas was confirmed as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court with a vote of 52 in favor and 48 against. This was a very close vote. He received support from 41 Republican senators and 11 Democratic senators. On the other hand, 46 Democratic senators and 2 Republican senators voted against him.

The process of confirming Thomas took 99 days from when his name was first given to the Senate until the final vote. This was one of the longest confirmation processes for a Supreme Court nominee in recent history. Also, the number of senators who voted against him (48 out of 100) was the highest for a successful nominee since 1881.

Eight days after being confirmed, on October 23, Thomas officially took his oaths of office. He became the 106th member of the Supreme Court. Justice Byron White swore him in during a ceremony at the White House.

Cultural Impact

The public discussion around the Thomas nomination had a big impact. Some people believe it helped raise awareness about important social issues in the United States. It is also linked to what some call the "Year of the Woman" in 1992. During that year, many women were elected to Congress, and some even called them the "Anita Hill Class."

Books and Films About the Nomination

Many books and films have been made about the Clarence Thomas nomination. These works explore the events and discussions that took place during the confirmation process.

Books Discussing the Nomination

Some authors have written books sharing their perspectives on the events. For example, David Brock wrote a book called The Real Anita Hill in 1993. However, he later changed his mind about his views in a 2003 book.

Ken Foskett, a reporter, wrote a book about Justice Thomas in 2004. He suggested that while some events might have happened, the way they were described might not be entirely accurate. He wondered if it was fair to use private actions as a political tool.

Scott Douglas Gerber wrote a book in 1998 about Justice Thomas's legal ideas. He said he wasn't sure whom to believe regarding the different accounts of the events.

Other authors, like Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson, wrote an investigative book called Strange Justice. They concluded that the evidence suggested Thomas had not been truthful during the hearings. Their book was very popular and received a lot of media attention.

Autobiographies

Both Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas have written books about their lives, where they discuss the nomination process.

In 1997, Anita Hill wrote her autobiography, Speaking Truth To Power. In it, she explained why she did not file a formal complaint at the time of the alleged events. She wrote that it was her choice, and that society needs to be more accepting of such claims.

Clarence Thomas published his memoirs in 2007. He also talked about the controversy. He described Anita Hill as someone who might overreact. He also said that the person described in the news was very different from the person he knew.

Films About the Hearings

The confirmation hearings have also been turned into movies:

- Strange Justice was a TV movie released in 1999 by Showtime. It starred Delroy Lindo as Thomas and Regina Taylor as Hill.

- Confirmation was a 2016 film by HBO. It starred Kerry Washington as Hill and Wendell Pierce as Thomas.

- Clarence Thomas also discussed his confirmation hearings in the 2020 documentary Created Equal: Clarence Thomas In His Own Words.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |