Florida mangroves facts for kids

The Florida mangroves are a special ecosystem found along the coasts of the Florida peninsula and the Florida Keys. Four main types of mangrove trees live here: red, black, white, and buttonwood. These trees grow in the warmer, southern parts of Florida because they don't like cold weather or frost. Mangroves are super important! They act like nurseries for young fish and provide homes for many birds and other animals that live near the coast.

Even though climate change might allow mangroves to grow further north, rising sea levels and strong storms could put existing mangrove forests in danger. Human activities like building new developments also threaten these important areas.

Quick facts for kids Florida mangroves |

|

|---|---|

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Neotropical |

| Biome | mangroves |

| Borders | Everglades and Southeastern conifer forests |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| States | Florida |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Critical/endangered |

Contents

Meet Florida's Mangrove Trees

Florida's mangrove areas are home to three main types of mangrove trees, plus one close relative.

Red Mangrove

Red mangroves are easy to spot because of their many roots that grow out of the trunk and branches, reaching down into the soil. These roots help the tree breathe in muddy areas where there isn't much oxygen. Red mangroves can grow very tall, sometimes over 100 feet in river deltas, or about 25-30 feet along shorelines. Their bark is gray on the outside but red inside. They have small white flowers and long, pencil-shaped seeds.

Black Mangrove

- Avicennia germinans

Black mangroves can grow up to 130 feet tall, but they usually average around 65 feet. They have special roots called pneumatophores that stick straight up out of the mud, helping them get air. Their bark is dark and scaly. You might see salt crystals on the underside of their leaves, which the plant pushes out. Black mangroves have white flowers that bees pollinate, and these flowers are a source of mangrove honey. Their seeds look like small lima beans when they start to grow.

White Mangrove

White mangroves typically grow up to 45 feet tall. They often grow straight up. If they are in very muddy areas, they might also have small, blunt roots sticking up for air. Their bark is smooth and white, and their leaves are oval-shaped. They have small yellowish flowers at the ends of their branches.

Buttonwood

The buttonwood is often found with mangroves, but it's sometimes called a "mangrove associate" rather than a true mangrove. Buttonwoods can grow up to 45 feet tall. They have tiny brownish flowers that form a seed cluster that looks like a button. These trees can grow in areas that are not always covered by tidal water, even on dry land. They have special glands on their leaf stalks that release extra salt and a sweet liquid called nectar.

Where Mangroves Grow (Zonation)

All three main mangrove species flower in the spring and early summer. Their seeds, called propagules, fall from late summer to early autumn. These plants have different ways of adapting to coastal conditions. Because of this, they usually grow in slightly overlapping bands or zones, almost like stripes, along the shoreline.

The red mangrove grows closest to the open water. Its many prop roots help hold the soil in place around its base. Further inland, you'll find the black mangrove. It doesn't have prop roots, but it has pneumatophores that grow up from its roots above the water. The white mangrove grows even further inland. It might have prop roots or pneumatophores depending on where it's growing. The buttonwood grows in shallow, brackish water (a mix of fresh and salt water), Florida swamps, or even on dry land, making it the furthest inland.

How Mangroves Reproduce

Mangroves have a very special way of reproducing. Unlike most plants that drop dormant seeds, mangroves are "viviparous." This means their seeds start to grow into young plants, called propagules, while they are still attached to the parent tree.

The propagules only drop into the water when they are ready. Once they leave the tree, they float for a certain amount of time (from 5 to 40 days, depending on the species). During this time, they continue to develop. When a propagule finds a good spot to land, it needs a little more time to settle before it starts to grow into a new tree.

Where Florida Mangroves Are Found

In 1981, Florida's mangrove forests covered about 430,000 to 540,000 acres. A huge 90% of these mangroves are in southern Florida, mainly in Collier, Lee, Miami-Dade, and Monroe Counties.

About 280,000 acres of mangrove forests are protected by federal, state, and local governments, as well as private groups. Most of these protected areas are in Everglades National Park. You can see a wide band of mangroves all along the southern end of the Florida peninsula, from Key Largo to Flamingo, and then inland behind the beaches of Cape Sable. A large area of mangroves also stretches up the Gulf coast to Marco Island, including the Ten Thousand Islands.

Mangroves are also found throughout the Florida Keys, though some areas have been lost due to development. Biscayne Bay also has many mangroves, but urban growth has cleared some northern parts of the bay. Smaller mangrove areas exist elsewhere, like in the Indian River Lagoon on the east coast, and along the Caloosahatchee River, Pine Island Sound, Charlotte Harbor, and Tampa Bay on the west coast.

Ideal Climate for Mangroves

Mangroves are tropical plants, meaning they can be killed by freezing temperatures. This is why they mostly grow in the warmer, southern parts of Florida. The warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf Stream help keep the coasts mild.

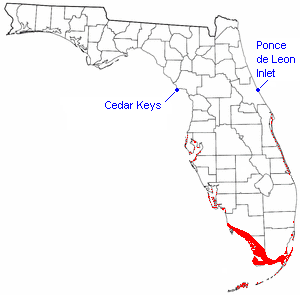

Florida's mangrove communities reach as far north as Cedar Key on the Gulf coast and Ponce de Leon Inlet on the Atlantic coast. Black mangroves are a bit tougher; they can regrow from their roots after a freeze and are found a little further north, even to Jacksonville on the east coast. Most of Florida is sub-tropical, not fully tropical, so the mangroves there tend to be shorter with smaller leaves than those in truly tropical areas. In deep south Florida and the Florida Keys, the tropical climate means mangroves can grow much larger because there are no frosts.

Loss of Mangrove Habitat

Human activities have affected Florida's mangrove areas. While the total amount of mangroves decreased by only about 5% over a century, some local areas have lost a lot. For example, the Lake Worth Lagoon lost 87% of its mangroves in the last half of the 20th century. Tampa Bay lost over 44% of its wetlands, including mangroves, during the 20th century. Three-quarters of the wetlands along the Indian River Lagoon, including mangroves, were changed for mosquito control. Efforts are now being made to restore natural water flow to some of these areas.

Animals and Plants in Mangrove Forests

The Florida mangrove system is a vital home for many species. It acts as a nursery for young fish, crustaceans, and mollusks, which are important for both sport and commercial fishing.

Fish and Shellfish

Many fish feed in the mangrove forests, including snook, mangrove snapper, schoolmaster snapper, tarpon, jack, sheepshead, red drum, hardhead silverside, young blue angelfish, young porkfish, lined seahorse, great barracuda, scrawled cowfish, and permit. Shrimp and clams also thrive here. It's estimated that 75% of the game fish and 90% of the commercial fish in south Florida rely on the mangrove system.

Birds

The branches of mangroves are perfect places for coastal and wading birds to rest and build their nests. Some birds you might see include the brown pelican, roseate spoonbill, frigatebird, double-crested cormorant, belted kingfisher, brown noddy, great white heron, Wurdemann's heron, osprey, snowy egret, green heron, reddish egret, and greater yellowlegs.

Endangered Species

Florida mangroves are also home to several endangered species:

- Smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata)

- American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus)

- Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

- Atlantic ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

- Eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon corais)

- Atlantic saltmarsh snake (Nerodia clarkii taeniata)

- Southern bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus leucocephalus)

- Peregrine falcon (Falco columbarius)

- Barbados yellow warbler (Dendroica petechia petechia)

- Key deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium)

- West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus)

Other Animals

Above the water, mangroves provide shelter for snails, crabs, and spiders. Below the water's surface, on the mangrove roots, you can find sponges, anemones, corals, oysters, tunicates, mussels, starfish, crabs, and Florida spiny lobsters.

Other Plants

Various epiphytes (plants that grow on other plants) can be found on mangrove branches and trunks. Under the water, the protected spaces created by the mangrove roots can shelter seagrasses.

How Climate Change Affects Mangroves

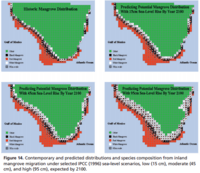

Climate change is a big and complicated issue. Scientists believe that mangroves are very sensitive to climate change. This ecosystem will be affected in three main ways: rising sea levels, fewer cold weather events, and stronger storms.

Rising Sea Levels

Since the 1940s, mangroves in southern Florida have moved about 2 miles further inland. This often happens as they take over freshwater marsh and swamp habitats. This could be bad for animals that rely on freshwater areas, like those in the Everglades.

Scientists predict that sea levels could rise significantly by the year 2100. While mangroves have kept up with past sea level rise, if the water rises too quickly, these forests could be in trouble. Mangroves on low-lying islands are especially at risk of being completely covered by water. However, mangroves on continental coasts have a better chance of finding new places to grow.

Warmer Temperatures

Florida's southern mangroves are tropical plants that don't like cold weather. Because winters are becoming less harsh, satellite images from the last 28 years show that mangroves are now growing further north in Florida. This is different from sea level rise, but both are caused by climate change.

Stronger Storms

With climate change, hurricanes in southern Florida are expected to become more severe. This could make mangrove populations shorter, with smaller trunks, and more red mangrove species. If big storms happen too often, mangroves might not have enough time to grow back. Mangroves also help protect coastlines by slowing down water surges from tsunamis and hurricanes. Losing mangroves could therefore be very bad for coastal communities facing stronger storms.

Helping Mangroves Survive

Even though local managers can't stop big changes like sea level rise, there are ways to help mangroves be stronger and survive. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and The Nature Conservancy suggest these strategies:

- Protect different types of mangrove habitats: This helps ensure that if one area is damaged, others can help replenish it.

- Identify and protect critical areas: Focus on places that are naturally strong enough to survive climate change.

- Reduce human impacts: Control pollution, sediment, and nutrient runoff from cities and developments.

- Create buffer zones: Set aside areas where mangroves can move inland as sea levels rise, and reduce negative effects from nearby land use.

- Restore damaged areas: Help mangroves grow back in places that have shown they can recover from climate change impacts.

- Keep connections strong: Make sure mangroves stay connected to freshwater sources, sediment, and other habitats like coral reefs and seagrasses.

- Monitor changes: Collect data and watch how mangroves respond to climate change over time.

- Be flexible with plans: Have adaptive strategies to deal with changes in where species live and environmental conditions.

- Support other ways of making a living: Help communities that depend on mangroves find other jobs (like making charcoal from coconut shells instead of mangroves, or producing mangrove honey) to reduce harm to the forests.

- Build partnerships: Work with different groups to get the money and support needed to deal with climate change impacts.