History of Dedham, Massachusetts, 1635–1699 facts for kids

The history of Dedham, Massachusetts, from 1635 to 1699, tells the story of its first settlers. These early pioneers arrived in 1635 and built their village on land the native people called Tiot. The town was officially recognized in 1636.

The settlers wanted to create a community where everyone lived by Christian values. For a while, they succeeded, but this perfect vision didn't last forever. Their government was unique, a mix of a "peculiar oligarchy" (rule by a few) and a "most peculiar democracy" (rule by many). Most free men could join the Town Meeting, but they soon created a group called the Board of Selectmen. Power often shifted between these two groups.

Establishing a church was another big challenge. They had to decide on its beliefs and choose a minister. At first, almost everyone in Dedham was a church member. However, as they sought a church only for "visible saints" (people who showed clear signs of strong faith), membership slowly dropped. A new idea called the "Half-Way Covenant" was suggested in 1657 and supported by the minister, but the church members voted against it.

Dedham's population grew from about 200 people in the early days to around 700 by 1700. Land was given out based on a person's social standing and family size. While land was generally given out carefully, it was also awarded to people who served the church and the community. In its early years, Dedham was quite isolated. With a small population, a simple farming economy, and free land, there wasn't much difference in wealth among the people.

As Dedham grew, new towns started to form from its original land, beginning with Medfield in 1651. Because so many towns originated from Dedham, it's often called the "Mother of Towns." Dedham is special because it has kept many detailed records from its early years. These records helped historians discover that the Fairbanks House is the oldest timber-frame house in America. They also confirmed that Mother Brook was America's first man-made canal and that the Dedham Public Schools was the country's first public school.

Contents

Founding Dedham: A New Beginning

Why Dedham Was Established

In 1635, there were rumors of war with local native people in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. People worried that the small towns along the coast were in danger. Also, these towns were built too close together. Because of this, the Massachusetts General Court decided to create two new towns further inland.

On May 6, 1635, the General Court allowed people from Watertown to start new towns. One group, led by Rev. Thomas Hooker, founded Hartford, Connecticut. Another group, led by Simon Willard, founded Concord, Massachusetts. Dedham and Concord helped ease the growing population pressure. They also created a buffer between the larger coastal towns and the native people further west.

Mapping the New Town

It wasn't until March 1636 that the General Court ordered the boundaries of Dedham to be mapped. A committee reported back in April, but the exact date the land was given to the first owners is unknown. The first grant was for about 3.5 square miles (9.1 km²) on the northeast side of the Charles River. This included parts of what is now Newton. It also included land on the other side of the river, which makes up about half of today's Dedham, Needham, Westwood, and Dover. This order came after twelve men asked the General Court for land south of the Charles River.

These twelve men, plus seven others, made a second request on August 29, 1636, for more land on both sides of the river. One of the new men was Robert Feake, whose wife was Elizabeth Fones, the widow of John Winthrop's son, Henry. Feake only attended three meetings, all in Watertown, and likely never visited Dedham. He was probably included for his political influence and received a farm lot and a house lot.

Naming the Town

The settlers asked the General Court to name their new town "Contentment." However, on September 7, 1636, the Court decided the "towne shall beare the name of Dedham." This name came from the English hometown of John Rogers or John Dwight, who were among the first to ask for the town's establishment. "Contentment" later became the town's motto. Many other settlers came from Suffolk, in eastern England.

The original land grant stretched from the southwestern border of what is now Boston (then Roxbury and Dorchester) to the borders of Rhode Island and Plymouth Colony. To the west were lands not yet granted. The fewer than 100 native people living on the land sold it for a small amount. Early settlers gave places names like Dismal Swamp and Devil's Oven.

Life in Early Dedham

First Settlers Arrive

The Algonquians called the area Tiot, meaning "land surrounded by water." Dedham was settled in the summer of 1636 by about thirty families. Most of these families were from the English middle class, mainly from Yorkshire and East Anglia. Only five of the people who signed the town agreement had gone to university. Many more would later serve the town, the church, and the colony. As Puritans, they came to Massachusetts to live and worship freely.

They traveled up the Charles River from Roxbury and Watertown in simple canoes. These first settlers, including Edward Alleyn and John Gay, paddled through the winding river. They were looking for the best land. The river twisted so much that it was hard to make progress.

They first landed near what is now Ames Street, close to the Dedham Community House and the Allin Congregational Church. This spot is known as "the Keye." In 1927, a stone bench and a memorial plaque were placed there. By March 1637, with homes built and fields planted, the settlers moved to their new village. The first town meeting in Dedham was held on March 23, 1637, with 15 men attending.

A Dream Community: The Utopia Idea

Dedham's early culture was similar to the English villages its settlers came from. However, as a settlement of English Puritans escaping hardship, Dedham was also very unique. It was meant to be a perfect society, like later communities such as the Amana Colonies. In its first years, Dedham was more than just a place to live; it was a spiritual community. It was called a "Christian Utopian Closed Corporate Community."

This meant it was Christian because they believed Christian love would unite them. It was Utopian because they tried to build the most perfect community possible. It was closed because new members were carefully chosen, and outsiders were often viewed with suspicion. And it was corporate because the community demanded loyalty from its members. In return, members received benefits like peace and good order.

Each original settler promised to live out Christian love every day. They expected everyone to be united in this love to bring peace to the whole community. People could even check on the private lives of townsmen. If someone's life wasn't seen as virtuous, changes could be ordered.

Only those committed to this ideal were allowed to join the town. If needed, people could be expelled. This commitment meant that church records show no arguments, no expulsions of Quakers or Baptists, and no witchcraft trials. The town agreement was meant to last forever, binding all future residents.

Poor residents of Dedham would be helped, but non-residents would be sent away. Besides paying taxes, each man was expected to work on community projects several days a month. Six days a year were set aside for road work, and each man had to work four of them. Townsmen also took turns serving in small jobs, like constable or fence viewer.

This wasn't communism. Puritans believed in natural differences among people, seeing it as God's plan. Still, the similar economic status kept social differences small and helped maintain harmony. Men could live their entire lives among their equals on their own land. This was similar to the larger plan John Winthrop hoped to build in Massachusetts.

Changes Over Time

The dream of a perfect society didn't last. Fifty years after the town was founded, the "policies of perfection" were no longer in charge. By the 1640s, the town allowed residents to fence their land in the common field. This meant they could grow whatever crops they wanted. Reducing the common field system meant farmers had fewer interactions with neighbors and fewer shared decisions.

Around 1660, not every newcomer was asked to sign the town agreement. This made them "second-class citizens." Laws restricting strangers were rarely enforced after 1675. Eventually, as some men became richer, they could hire others to do their community work or serve in office for them.

Also, around this time, the "loving spirit" promised in the agreement started to disappear. Records show open disagreements, first about where people sat in the meetinghouse. In 1674, people began sitting wherever they wanted. This growing sense of equality didn't please everyone. A committee was formed to deal with those who didn't sit in their assigned seats.

Some people refused to meet with the committee, and others didn't like its decisions. With unhappiness continuing, Ruling Elder John Hunting was asked to talk to those involved. Hunting wasn't successful either. So, the selectmen fined those who didn't sit in their assigned seats five shillings. One-third of the fine went to the person who reported the offender, and the rest went to the town. After Nathanial Bullard reported many townsmen, he seemed so annoying and greedy that the fine was removed.

The number of "yes" and "no" votes also began to be recorded. Before, decisions were made by everyone agreeing. As the century went on, residents were more likely to use the court system to solve problems. This was unheard of before, as the town agreement had a way to settle disputes.

Dedham was quite isolated in its early years. But as time passed, it became more connected to the outside world. This meant less focus was placed on the local community. In 1661, Richard Ellis refused to serve as Town Clerk, which would have been unthinkable a decade earlier. In 1663, a committee that evaluated land given to "praying Indians" asked to be paid for their expenses. This showed that the days of doing community service without expecting money were over.

By 1686, much of the founders' perfect vision was gone. By the end of the century, public disagreements were common, and decisions were made by majority vote, not by everyone agreeing. The town agreement was no longer followed as a guide for every decision by Dedham's 50th anniversary. That it lasted into the second generation was surprising. Still, the town remained small and grew slowly, with few changes to its government or old ways.

By 1675, taxpayers paid more to the county and colony than to the town. This showed the growing importance of regional governments and the cost of the colony expanding westward. After 1691, as the county became more powerful, the town started following laws more closely to avoid fines.

How Dedham Was Governed

The colonial settlers first met on August 18, 1636, in Watertown. By September 5, 1636, their group grew from 18 to 25 people ready to move to the new community. However, by November 25, so few people had actually moved to Dedham. So, the group voted that every man must move to Dedham permanently by the next November 1st, or they would lose their land. A few young, single men went to spend the winter there, including Nicholas Phillips and Ezekiel Holliman.

The first town meeting in Dedham was on March 23, 1637. Most of the landowners were there, suggesting most were living in Dedham by then. For the first fifty years, Dedham had a stable and peaceful government. The town elected wealthy, experienced friends as Selectmen and trusted their decisions. The town agreement also required mediation for disputes, which helped keep society stable. There wasn't a system of checks and balances as much as people simply chose to limit themselves.

Because of its unique features, Dedham was both a "peculiar oligarchy" (rule by a small group) and a "most peculiar democracy" (rule by the people). This is because voting rules changed often, sometimes limiting who could vote, and sometimes expanding it.

The Dedham Covenant

While the first settlers had to follow the General Court, they had a lot of freedom to set up their local government. The first public meeting was on August 18, 1636. Eighteen men were there, and they signed the town agreement, called the covenant. It was a diverse group, including farmers, wool-combers, and butchers.

The covenant described the perfect society they hoped to build and how they would achieve it. They promised to "mutually and severally promise amongst ourselves and each to profess and practice one truth according to that most perfect rule, the foundation whereof is ever lasting love." This agreement was meant to last forever and bind future generations. It kept out those who disagreed or didn't share their religious beliefs, but it wasn't a government ruled by religion. Before a man could join, he had to answer questions publicly to see if he was suitable.

They worked hard to solve disagreements before they became big problems. The covenant also said that differences would be settled by one to four other town members. This way of solving problems was so good that they didn't need courts. Once a decision was made, everyone was expected to follow it without further argument. For Dedham's first fifty years, there were no long disputes, which were common in other towns.

Town Meetings

The town meeting was the main way local decisions were made. Dedham's founders met to discuss their new community even before the General Court defined town government. Early meetings were informal, with all men likely taking part. Attending meetings was seen as very important for the community. Decisions were made by everyone agreeing. The town meeting had almost unlimited power, even when it didn't fully use it.

Wealthier voters were more likely to attend meetings. However, even though only 58 men could vote and make decisions, and even though everyone had to live within one mile of the meeting place, and even though missing a meeting meant a fine, only 74% of eligible voters actually showed up between 1636 and 1644.

A colony law required all voters to be church members until 1647, though it might not have been enforced. Even if it was, 70% of the men in town would have been able to vote. The law changed in 1647, and in Dedham, all men over 24 could vote. The colony changed the rules sometimes, but sometimes old rules still applied to certain people. In colony-wide elections, only church members could vote. Regardless of whether they could vote, records show that all men could attend and speak.

The Selectmen

The whole town used to gather regularly to handle public business. But they found that "the general meeting of so many men... has wasted much time." So, on May 3, 1639, seven selectmen were chosen "by general consent." They were given "full power to contrive, execute and perform all the business and affairs of this whole town." The leaders chosen were skilled men who shared the same values and goals as their neighbors. They were given great authority. If a man served three terms and the community was happy with him, he often stayed on the board for many years.

Soon, the selectmen had almost complete control over local administration. Almost all townsmen would have to appear before them at some point during the year. They might ask to swap land, remove firewood from common lands, or for other reasons. The selectmen wrote most of the town's laws and collected taxes. They could also approve spending. They also acted as a court, deciding who broke rules and issuing fines. As the selectmen became more active, the Town Meeting became less involved.

Selectmen were the most powerful men in town. They were few in number, older, and relatively wealthy. They were also often church members. While wealth wasn't required to serve, it helped get elected. Men who weren't church members could still hold town office. The work of being a selectman could take up to a third of their time during busy seasons. They served without pay and moved up from lower offices. In return, they gained great respect and were often chosen for other important positions.

Town Meeting and Selectmen: A Shifting Balance

After the Board of Selectmen was created, Town Meetings were usually held only twice a year. They generally stuck to the agenda prepared by the selectmen. In fact, the Meeting often sent issues to the Selectmen to handle or to "prepare and ripen the answer" to a difficult question. Town Meeting usually handled only routine business, like electing officers or setting the minister's salary, leaving other matters to the selectmen.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, the Town Meeting started to take back more power. Fewer decisions were left to the selectmen. Over 30-40 years, small changes brought the power back to the meeting and away from the board. This restored a balance of power between the two groups, which, in theory, had always existed but had been tilted towards the selectmen.

One main way they did this was by calling more meetings. In the first 50 years, town meetings were held about twice a year. But by 1700, they were held four or five times a year. The agenda also grew longer and included an open item that allowed them to discuss anything they liked, not just topics the selectmen put on the warrant.

Building the Church and Faith

On July 18, 1637, the Town voted to accept a group of very religious men. This group would greatly change the town's future. Led by John Allin, they included Michael Metcalf and Eleazer Lusher. One man, Ezekiel Holliman, realized that as a religious liberal, he wouldn't be welcome. So, he moved to Rhode Island with Roger Williams.

Establishing the Church

Founding a church was even harder than founding a town. Meetings were held in late 1637 and were open to "all the inhabitants who affected church communion." They would meet in different homes every fifth day to discuss questions that would help establish a peaceful society and prepare for spiritual life. Everyone was expected to speak "humbly and with a teachable heart."

After getting to know each other, they wondered if they, as a group of Christians in the wilderness, had the right to form a church. Their understanding of the Bible led them to believe they did. So, they continued to establish a church based on Christian love, but one that also had rules for membership.

It took months of talks to agree on and write a church covenant. The group set up thirteen principles, written as questions and answers, that formed the church's beliefs. Once the beliefs were agreed upon, 10 men were chosen by John Allin, with help from Ralph Wheelock. Their job was to find the "pillars" or "living stones" on which the church would be built.

These chosen men met separately. They decided that six of their own—Allin, Wheelock, John Luson, John Frary, Eleazer Lusher, and Robert Hinsdale—were suitable to form the church. These worthy men then presented themselves to the entire community for approval.

Finally, on November 8, 1638, two years after the town was founded and one year after the first church meetings, the covenant was signed, and the church was officially formed. Guests from other towns were invited to the event. They sought the "advice and counsel of the churches" and the "countenance and encouragement of the magistrates."

Church Membership

Only "visible saints" were considered pure enough to become members. This meant they had to publicly declare their faith and live a holy life. Just being baptized wasn't enough, because then "papists, heretics, and many visible atheists that are baptized must be received." A group of the most religious men interviewed everyone who wanted to join the church. To become a member, a person had to "pour out heart and soul in public confession" and let their deepest desires be examined by others. All others had to attend sermons at the meetinghouse but couldn't join the church, receive communion, be baptized, or become a church officer.

Once the church was established, residents, whether members or not, gathered several times a week to hear sermons and lectures on practical faith. Between 1644 and 1653, 80% of children born in town were baptized. This shows that at least one parent was a church member. Servants and masters, young and old, rich and poor, all joined the church. Non-members were not treated unfairly. For example, several men were elected Selectmen before they became church members.

By 1663, almost half the men in town were not members. This number grew as more second-generation Dedhamites grew up. This decline was clear across the colony by 1660. It was worried that the third generation, if born without a single parent who was a member, couldn't even be baptized.

To solve this, an assembly of ministers from Massachusetts supported a "Half-Way Covenant" in 1657 and again in 1662. This allowed parents who were baptized but not full church members to have their children baptized. However, these parents were denied other church privileges, like communion. Allin supported this idea, but the church members rejected it, wanting a pure church of saints.

Church Leaders

Even though John Allin's salary was given freely by members and non-members, he was always paid on time. This shows how much the community respected him. In the 1670s, as the town's perfect vision faded, a tax was needed to make sure the minister was paid.

Just before Allin's death, they decided to continue paying the salary through voluntary assessed amounts. Several other votes followed in the next 16 months when it was clear the system wasn't working. No solution was found, and the church was constantly behind in paying William Adams' salary.

| Minister | Years of service |

|---|---|

| John Allin | 1638–1639 |

| John Phillips | 1639-1641 |

| John Allin | 1641–1671 |

| Vacant | 1671–1673 |

| William Adams | 1673–1685 |

| Vacant | 1685–1693 |

| Joseph Belcher | 1693–1723 |

John Allin and John Phillips

John Phillips was respected and learned, but he couldn't become the church's first minister. He refused offers to settle in Dedham twice. Instead, he went to the Cambridge church, where Harvard College had recently been founded. The search for a minister took several more months. Finally, John Allin, the leader of the small group of church members, was chosen as pastor. John Hunting was selected as Ruling Elder over Ralph Wheelock, who also wanted the position. They were officially appointed on April 24, 1639.

Phillips left Cambridge at the end of 1639 and decided to come to Dedham after all. However, he quickly became unhappy in his new role and returned to his old church in England in October 1641. Like in England, Puritan ministers in the American colonies were usually appointed for life. Allin served for 32 years. He received a salary of between 60 and 80 pounds a year. When land was divided, his name was always at the top of the list, and he received the largest plot.

William Adams

After Allin's death, the church was without a permanent minister for a long time. William Adams, who graduated from Harvard College two weeks before Allin's death in August 1671, had connections to Dedham and attended Allin's funeral. By December, he had already been asked several times to preach in Dedham.

He finally accepted an offer to preach in Dedham and did so on February 17, 1672. He rejected the full offer several times before agreeing to preach on a trial basis in September 1673. He moved to Dedham on May 27, 1673, and was officially appointed on December 3, 1673. Adams served until his death in 1685. Aside from a few small disagreements, his time in Dedham was mostly peaceful. Given the church's rejection of the Half-Way Covenant, which the colony's clergy supported, Adams may have been a last choice. Eventually, the church would change its mind and accept the Half-Way Covenant.

Joseph Belcher

After Adams died, the church was without a minister from 1685 to 1692. Following his death, the church again rejected the Half-Way Covenant. As a result, even though many preachers visited, and several young men were offered the position, the church couldn't find a minister to stay permanently.

At the end of 1691, the church voted again to accept the half-way covenant. They declared that Allin was right to have tried to get them to accept it earlier. A new minister, Joseph Belcher, began preaching in March 1692 and was officially appointed on November 29, 1693. He remained in the position until the autumn of 1721 when illness prevented him from preaching.

Meetinghouses

Almost immediately after arriving, the settlers began holding prayer meetings and worship services under various trees. On January 1, 1638, the Town voted to build a meetinghouse. It was first planned for High Street, near today's border with Westwood. But those living on East Street argued it should be more central. It's unclear when the building was finished, but probably not before November 1638. An addition was ordered in 1646, but the plastering wasn't done until 1657.

A vote to buy a bell was made in 1648, but a bell wasn't hung until February 1652. With the bell, the Town no longer needed to pay Ralph Day to beat a drum to announce meetings. The bell was rung not only for public meetings but also to warn of fire, announce a death, and signal the start of church services.

Until a separate schoolhouse was built, the meetinghouse also served as a classroom. The roof of the east gallery also stored the town's gunpowder after a 1653 vote.

A vote to build a new meetinghouse, held on February 3, 1673, used white corn for "yes" and red corn for "no." The vote was almost entirely in favor. The new meetinghouse was built on June 16, 1673.

Dedham's Growing Population

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1637 | 31 men, plus their families |

| 1640 | >200 |

| 1648 | ~400 |

| 1651 | ~100 families |

| Late 1650s | 150+ men, plus others |

| 1686 | >600 |

| 1700 | 700–<750 |

On June 3, 1637, Ruth Morse was the first child born to white parents, John and Annis, in Dedham. The average population during the 1600s was about 500 people. This was slightly larger than the average English village at the time. With people moving in or out, almost all growth came from births, and declines from deaths. The average age for first marriages was 25 for men and 23 for women. This was younger than the European average of 27 for men and 25 for women. Younger marriages led to more births. There were also fewer deaths, partly because Dedham was spared from diseases, famine, and extreme weather that affected parts of Europe.

By the 1650s, many different types of men lived in Dedham. These included single men, family men, the wealthy, and servants. Some bought land but never settled there. Some left soon after arriving, either for other towns or back to England. A few died before they could do much.

Daily Life of Early Settlers

Each man received small house lots in the village. They also got extra strips of land for farming, meadows, and woods. Each strip was in a common field. The community decided what crops to grow and how to care for and harvest them. This common field system brought people into regular contact and kept farms close to the village center. There are no records of land clearing, so it was likely used by native people before. Each man also got a plot within the field to farm. Residents grew corn, beans, peas, and pumpkin. Later, those with larger plots planted wheat, rye, barley, and oats.

Land was given out carefully. No family received more land than they could currently use. Married men received 12 acres, with four acres being swamp. Single men received eight acres, with three acres being swamp. Land was also given for service to the church and community. This was a practice already set by the General Court.

Land was given based on several things. First, the number of people in the household mattered. Servants were counted as part of a free man's property. Land was also given based on the "rank, quality, desert and usefulness" of the owner, whether in church or government. Finally, it was thought that men who had a trade other than farming should have the materials they needed. Also, those who could improve more land should have that considered.

Dedham's Isolation

Most of the first settlers and early arrivals stayed in Dedham for the rest of their lives. Less than two percent of men moved into town each year, and less than one percent left. Because people didn't move much, the town became a "self-contained social unit," almost completely separate from the rest of the world. This stability was a very important part of Dedham's history. A century after it was settled, moving in and out was still rare. Of every 10 men born in Dedham between 1680 and 1700, eight would die there.

From its earliest days, Dedham was closed to outsiders unless current residents specifically welcomed them. Soon after the town was founded, in November 1636, the Town Meeting voted not to allow any land sales unless the buyer already lived in town or was approved by most voters. On August 11, 1637, 46 house lots had been marked out, and they voted to stop accepting new residents.

Twenty years after the settlement began, those who had worked hard to settle the land worried that as the population grew, their land shares would become smaller. On January 23, 1657, town growth was further limited to descendants of those living there at the time. Newcomers could settle there if they shared the same beliefs, but they would have to buy their way into the community. Land was no longer freely available for those who wanted to join.

Wealth and Work

With a small population, a simple farming economy, and free land, there wasn't much difference in wealth. In the early days, anyone considered poor was likely a sick widow, an orphan, or someone who couldn't manage their money well. In 1690, the poorest 20% of the population owned about 10% of the property.

At least 85% of the people were farmers, or "yeoman" or "husbandman" as they called themselves. There were also people who served the farmers, like millers, blacksmiths, or shoemakers. Like in the English countryside, they were mostly subsistence farmers. This means they grew enough food for their families but didn't specialize in any cash crops or particular animals. The first homes were all quite similar, built with boards, stone fireplaces, and chimneys. The roofs were covered with thatch. The first floor had a living room and kitchen, and sleeping areas were in the attic above, reached by a ladder.

Each person might own two changes of clothes plus a good suit or cloak. A family might have a little silver or pewter. They typically owned a Bible, pots, pans, bowls, and storage bins. Outside the house, in the barn or lean-to, would be farming tools and a few bushels of crops. For animals, one or two horses, along with several cattle, pigs, and sheep, were common.

Labor and Servants

Single people, including adult children of residents, were not allowed to live alone unless they had enough money to set up their own household with servants. Each year, one day was set aside to assign young adults to other households as subordinates. This practice helped keep the family labor system going, which was the basis of the local economy. It also aimed to prevent "sin and iniquity" that they believed came from living alone. Selectmen also had the power to take children out of homes and put them to work in other households. If a household didn't pay their full taxes, or if it wasn't seen as efficient enough, children could be removed and placed in the homes of richer men.

In 1681, there were 28 servants in 22 of the 112 households in town. All but four were children, and 20 of the servants were white. There were ten boys, eight girls, two "Negro boys," two "Indian boys," one "lad," and one "English girl." There was also one man, one "Negro man," and two "maids." Servants were in 20% of households but made up only 5% of the population. Most of them soon became independent farmers. Many children who lived as servants in Dedham may have been taken in partly out of kindness. After King Philip's War, there were many orphaned children. Dedham had strong ties to Deerfield, so it's thought that some of the children—both white and Native American—were affected by the war.

Relations with Native Peoples

In April 1637, the Town voted to start keeping watch to prevent attacks from native people. By May, however, they complained about the time and money spent on patrols. A group was sent to Watertown to ask Thomas Cakebread to move to Dedham because of his "knowledge of martial affairs." Just a year later, the new town of Sudbury convinced him to move there by giving him control over the milling business in town.

New settlements, which later became separate towns, were created for several reasons. One was to act as a buffer between native peoples and the village of Dedham. Medfield and Wrentham, which separated from Dedham, each experienced at least one attack during the 17th century. These attacks would have otherwise hit Dedham itself. Dedham had also served as a buffer between native peoples and the coastal towns, as well as against the free-thinking followers of Roger Williams.

In the 1680s, the Town leaders sought out and bought the rights to the land from every native person who claimed to own land or hold title.

King Philip's War

During King Philip's War, men from Dedham went to fight, and several died. More former Dedhamites who had moved to other towns died than men still living in Dedham. These included Robert Hinsdale, his four sons, and Jonathan Plympton, who died at the Battle of Bloody Brook. John Plympton was killed after being marched to Canada with Quentin Stockwell.

Zachariah Smith was passing through Dedham on April 12, 1671. He stopped at Caleb Church's home in the "sawmill settlement" on the Neponset River. The next morning, he was found dead. A group of praying Indians found him, and suspicion fell on a group of non-Christian Nipmucs who were also heading south. This was seen as the "first actual outrage of King Phillip's War." One of the Nipmucs, a son of Matoonas, was found guilty and executed on Boston Common. Dedham then prepared its cannon, which the colony had given them in 1650, for an attack that never came.

After the attack on Swansea, the colony ordered the militias of several towns, including Dedham, to have 100 soldiers ready to march within an hour. Captain Daniel Henchmen took command of the men and left Boston on June 26, 1675. They arrived in Dedham by nightfall. The troops became worried by an eclipse of the moon, which they saw as a bad sign. Dedham was mostly spared from the fighting and was not attacked. However, they did build a fortification and offered tax cuts to men who joined the cavalry.

Plymouth Colony governor Josiah Winslow and Captain Benjamin Church rode from Boston to Dedham. They took charge of the 465 soldiers and 275 cavalry gathering there. Together, they left on December 8, 1675, for the Great Swamp Fight. When the commanders arrived, they also found many teamsters, volunteers, servants, and other people. Dedham's John Bacon died in the battle.

During the battle in Lancaster in February 1676, Jonas Fairbanks and his son Joshua both died. Richard Wheeler, whose son Joseph was killed in battle the previous August, also died that day. When Medfield was attacked, they fired a cannon to warn Dedham. Residents of nearby Wrentham left their community and fled to the safety of Dedham and Boston.

Pumham, one of Phillip's main advisors, was captured in Dedham on July 25, 1676. Several Christian Native Americans had seen his group in the woods, almost starving. Captain Samuel Hunting led 36 men from Dedham and Medfield and joined 90 Native Americans to find them. Fifteen of the enemy were killed, and 35 were captured. Pumham, though badly wounded, grabbed an English soldier and would have killed him if another settler hadn't helped.

John Plympton and Quentin Stockwell were captured in Deerfield in September 1677 and marched to Canada. Stockwell was eventually rescued and wrote about his experience, but Plympton was killed.

Praying Indians

In the mid-17th century, Reverend John Eliot converted many native people in the area to Christianity. He taught them how to live a stable, farming life. He converted so many that the group needed a large piece of land to grow their own crops. John Allin helped Eliot. It was likely through his influence that Dedham agreed to give up 2,000 acres (8.1 km²) of what is now Natick to the "praying Indians" in 1650.

In return, Dedham expected the Native Americans to settle only on the northern bank of the Charles River. They were not to set any traps outside their land grant and give up all claims to any other land in Dedham. The native people, who didn't have the same ideas about private property as the English, settled on the south side of the river and set traps within Dedham's boundaries. Disputes began in 1653, and they tried compromise, arbitration, and negotiation.

In 1661, Dedham stopped trying friendly solutions and took their native neighbors to court. They sued for ownership of the land the Native Americans were living on. The case was about the Native Americans' use of land along the Charles River. The native people claimed they had an agreement with the Town Fathers to use the land for farming, but Dedham officials disagreed. While the law was on the town's side, Eliot argued that the group needed their own land.

The case eventually went before the General Court. The Court granted the land in question to the Native Americans. To make up for the lost land, Dedham settlers were given another 8,000 acres (32 km²) in what is now Deerfield, Massachusetts. Dedham's actions in this case were marked by "deceptions, retaliations, and lasting bitterness." They bothered their native neighbors with small accusations even after the matter was settled.

New Towns Form from Dedham

As Dedham's population grew, residents began moving further from the town center. Within 25 years of the first settlement, Dedham had a philosophy of expansion. In the 1670s, with each new land division, farmers started taking shares close to their existing plots. This, along with special "convenience grants" near their fields, allowed townsmen to combine their land. A market for buying and selling land also appeared. Farmers would sell land far from their main plots and buy land closer to them.

When this started happening, residents first moved their barns closer to their fields, and then their homes too. By 1686, homes gathered in several outlying areas, pulling their owners away from the daily life of the village center. As the numbers in these outer areas grew, they began to break off and form new towns. This started with Medfield in 1651.

Until 1682, all Dedhamites had lived within 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of the meetinghouse. After Walpole left, Dedham had only 25% of its original land area. Many Dedham residents also became early settlers of Lancaster, Hadley, and Sherborn, Massachusetts.

| Community | Year incorporated as a town | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Medfield | 1651 | The first town to leave Dedham. |

| Natick | 1659 | Established as a community for Christian Native Americans. |

| Wrentham | 1673 | Southeast corner of town was part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. |

| Deerfield | 1673 | Land was granted to Dedham in return for giving up Natick. |

| Needham | 1711 | |

| Medway | 1713 | Separated from Medfield. The land was granted to Dedham in 1649. |

| Bellingham | 1719 | |

| Walpole | 1724 | |

| Stoughton | 1726 | Part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. Separated from Dorchester. |

| Sharon | 1775 | Part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. Separated from Stoughton. |

| Foxborough | 1778 | Part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. |

| Franklin | 1778 | Separated from Wrentham. |

| Canton | 1797 | Part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. Separated from Stoughton. |

| Dover | 1836 | Then known as Springfield, it became a precinct of Dedham by vote of Town Meeting in 1729; relegated to a parish the same year by the General Court. Created the Fourth Precinct by the General Court in 1748. |

| Hyde Park | 1868 | 800 acres taken from Dedham, along with land from Dorchester and Milton. |

| Norfolk | 1870 | Separated from Wrentham. |

| Norwood | 1872 | Created a precinct with Clapboard Trees (Westwood) in 1729. Became its own precinct in 1734. |

| Wellesley | 1881 | Separated from Needham |

| Millis | 1885 | Separated from Medfield. |

| Avon | 1888 | Part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. Separated from Stoughton. |

| Westwood | 1897 | Joined with South Dedham (Norwood) to create Second Precinct in 1729. Returned to First Precinct in 1734. In 1737 became Third Precinct. Last community to break away directly from Dedham. |

| Plainville | 1905 | Eastern section of town was part of the Dorchester New Grant of 1637. Separated from Wrentham. |

Medfield: The First to Leave

Most of today's Medfield had been granted to Dedham in 1636. However, lands on the western bank of the Charles River had been given out by the General Court to individuals. For example, Edward Alleyn received 300 acres in 1642. Dedham asked the General Court for some of those lands. On October 23, 1649, the Court agreed, as long as Dedham established a separate village there within one year.

Dedham sent Eleazer Lusher, Joshua Fisher, and others to map out an area three miles by four miles. The colony sent representatives to set the boundaries on the opposite side of the river. The land Dedham contributed became Medfield. The land the colony contributed eventually became Medway.

These separations were not easy. When Medfield left, there were disagreements about who was responsible for public debts and about land use. Some residents who didn't move to the new village wanted rights to the meadows. Others thought the land should be given freely to those who would settle there. A compromise was reached: those moving to the new village would pay £100 to those who remained, instead of giving them rights to the meadows. This was later reduced to £60 if paid over three years, or £50 if paid in one year.

Tax records show that those who moved to the new village came from Dedham's middle class. Among the first 20 men to move were Ralph Wheelock and Robert Hinsdale. By 1664, several of their sons joined them, as did Joshua Fisher and his son John. Those who moved often did so with family members. Many would later move from Medfield to other inland communities. It's also possible that those who left Dedham for Medfield were unhappy with the political or social situation in Dedham.

The Town Meeting voted to release Medfield on January 11, 1651, and the General Court agreed the following May.

Wrentham: A New Settlement

In 1660, after the Medfield separation, five men were sent to explore the lakes near George Indian's wigwam. They were to report back to the selectmen. The report from these men, including Daniel Fisher and Joshua Fisher, was so exciting that in March 1661, they voted to start a new settlement there. The Town then voted to send Ellis and Timothy Dwight to negotiate with King Phillip to buy the title to the area known as Wollomonopoag.

They bought 600 acres of land for £24, 6s. The money was paid by Captain Thomas Willett, who went with Ellis and Dwight. The Town voted to tax the cow commons to repay him. But some thought the money should be paid by those moving to the new village. This disagreement meant Willett wasn't paid back for several years.

After the new community's boundaries were set, the Town voted to give up all rights to the land. In return, the new landowners would pay Dedham £160 over four years, starting in 1661. By January 1663, however, little progress had been made toward establishing a new village. A meeting was called, and the 10 men who volunteered raised concerns about their ability to move forward.

After much discussion, they decided not to give the 600 acres to the pre-selected men. Instead, they would mark out lots and award them by lottery. Those who had already started improving their lots could keep them. Land for a church, burial ground, training ground, roads, and officer lots were not included. Everyone was free to buy and sell their lots.

Not much happened at Wollomonopoag until 1668. At that time, a report came that native people were planting corn and cutting trees on the land Dedham had bought. Eleazer Lusher was asked to send the native people a letter warning them to "depart from that place and trespass no further." Samuel Fisher read it aloud to them. They replied that they intended to stay on the land. Although they still hadn't paid him back for the land, the Town then asked Willett to speak with King Phillip and ask him to help.

There's no record of Phillip's response. But in August 1669, the Town Fathers received a strange letter from him. He offered to negotiate for more land if they would quickly send him a "holland shirt." Dwight and four others were appointed to negotiate with him again, if Phillip could prove he, and not another sachem, had the rights to the land. In November, they agreed to clear the title for £17 0s 8d. There's no record of whether a shirt was traded.

Samuel Sheares lived alone at Wollomonopoag for some time before a new settlement attempt began in 1671. Five men, John Thurston, Thomas Thurston, Robert Weare, John Weare, and Joseph Cheeney, moved there with him. The next year, Rev. Samuel Man, a former teacher in the Dedham Public Schools, followed. Robert Crossman was hired at the same time to build a corn mill. Man was chosen by the new village residents to be their minister. His decision was approved by a committee including John Allin and Eleazer Lusher.

Those who moved there were from Dedham's middle class. They were mainly people from outside Dedham who had bought land there, and second-generation Dedhamites who moved without their parents. Without these outsiders, it's questionable whether the new community would have survived.

Soon, however, the Wollomonopoag settlers complained that those in the village center were keeping them dependent. They were upset about landowners who didn't live there but whose land value increased because of the inhabitants' work. These landowners refused to pay taxes to support the community. They also complained that the town government was so far away that they felt left out and lacked money. Constables refused to travel to Wollomonopoag to collect taxes or make social judgments.

With Dedham's Board of Selectmen's approval, the General Court separated the new town of Wrentham, Massachusetts on October 16, 1673.

Deerfield: Land for Compensation

After the "Praying Indians" were given 8,000 acres (32 km²) in what is now Natick, the General Court gave Dedham's landowners 8,000 acres (32 km²) as compensation. The question of how to handle this extra land puzzled the town for some time. Some wanted to sell the rights to the land and take the money. Others wanted to find a suitable location and claim it.

The Town sent Anthony Fisher, Jr., Nathaniel Fisher, and Sgt. Fuller to explore an area called "Chestnut Country" in 1663. Two weeks later, they reported that the area was hilly, with few meadows, and generally unsuitable. After another potential location was claimed by others before Dedham could, a report came about land at a place called Pocomtuck, about 12 or 14 miles from Hadley. They decided to claim this land before others could.

Joshua Fisher, Ensign John Euerard, and Jonathan Danforth were assigned by the selectmen to map the land. In return, they would receive 150 acres. Two weeks later, Fisher asked for 300 acres instead. The selectmen agreed, if he provided a map of the land. Fisher's map and report were given to the General Court. They agreed to give the land to Dedham, provided they settled the land and "maintain the ordinances of Christ there" within five years. Fisher was the first in the region to use a compass for surveying.

Daniel Fisher and Eleazer Lusher were sent to buy the land from the Pocomtuc Native Americans living there. They worked with John Pynchon, who had a relationship with the native people. He obtained a deed from them. Pynchon submitted a bill for £40 in 1666. But a tax on the cow commons to pay it wasn't put in place until 1669. By then, the bill had risen to over £96, and he wasn't paid in full until 1674.

The drawing of lots took place on May 23, 1670. By this time, many rights had been sold to people from outside Dedham or its daughter towns. Even before that, Robert Hinsdale's son Samuel moved into the area and began living on the land without permission. He was eventually joined by his father and brothers.

Hard feelings arose because of the new settlement's distance from Dedham and the fact that the landowners were not strictly "a Dedham company." On May 7, 1673, the General Court separated the town of Deerfield, with additional lands. This was on the condition that they establish a church and settle a minister within three years.

Natural Resources and Early Innovations

Mother Brook: America's First Canal

Both the Charles River and the Neponset River ran through Dedham and close to each other. However, both were slow-moving and couldn't power a mill. But there was a 40-foot (12 m) elevation difference between the two. This meant a canal connecting them would be fast-moving. In 1639, the town ordered a 4,000-foot (1,200 m) ditch to be dug between the two rivers. This would allow one-third of the Charles' water to flow down what would become known as Mother Brook and into the Neponset. Abraham Shaw began building the first dam and mill on the Brook in 1641. It was completed by John Elderkin, who later built the first church in New London, Connecticut. A fulling mill (for processing cloth) was established in 1682.

Trees: Early Conservation Efforts

It's estimated that each family would burn enough wood in a year to clear four acres of land. Remembering the social problems in Boston when almost every tree was cut down within three years of its founding, Dedham strictly enforced rules against cutting trees on public and unallotted lands. Preserving these trees became "one of the first conservation projects in New England."

The Old Avery Oak Tree, named for Dr. William Avery, stood on East Street for centuries. The builders of the USS Constitution once offered $70 to buy the tree, but the owner wouldn't sell. The Avery Oak, which was over 16 feet (4.9 m) around, survived the 1938 New England hurricane but was toppled by a violent thunderstorm in 1973. The Town Meeting Moderator's gavel was carved from its wood.

Swamps, Bogs, and Meadows

Owners of swampland were required to drain them. This served several purposes. First, it removed habitats for dangerous wild animals. Second, it made it easier to cut down trees on the land when lumber was in high demand for building and burning. Clearing a swamp turns it into a bog, and draining a bog turns it into a meadow. Meadowland was in high demand for raising cattle. The rich meadows along the Charles River were a major reason for choosing Dedham's location.

The General Court had given 300 acres to Samuel Dudley along the town's northeast border, between East Street (an old Native American trail) and the river. Four men, Samuel Morse, Philemon Dalton, Lambert Genere, and John Dwight, bought the meadowland from Dudley for £20. Needing more meadows immediately, the Town bought it from them for £40, doubling their initial investment. This land became known as Purchase Meadows and was divided into herdwalks for use by residents of different districts.

A road, now known as Needham Street, was laid out along the banks of the Charles River in 1645. But it was often washed out or flooded. The road brought farmers from their homes in the village to the planting field at Great Plain, in what is now Needham. Besides washing out the road, the waters often flooded the "broad meadow," further limiting needed pasture.

It was discovered that the river, which runs east for many miles, suddenly turned southeast, then north, and then northwest. At this point, it flowed close to where it originally turned. Despite a run of seven or eight miles, it only fell three feet, causing much of the flooding. In January 1652, the Town Meeting voted to dig a 4,000-foot (1,200 m) ditch connecting the Charles River at either end of its great loop. It wasn't finished for nearly two years. But once it was, it channeled water directly from the high side to the low side. This also created an island, now the Riverdale neighborhood.

Animals and Wildlife

Wild animals were a problem, and the town offered rewards for killing several of them. If someone brought in an inch and a half of a rattlesnake, plus the rattle, they received six pence. A ten-shilling reward was placed on wolves, and it was often paid. There was also a reward for wildcats. Between 1650 and 1672, more than 70 wolves were killed in Dedham.

For a short time, the Town hired professional hunters and a pack of dogs. Dogs could also be a problem, though. In 1651, the Town authorized Joshua Fisher to keep them from bothering people in the meetinghouse. On May 27, 1647, Daniel Fisher gave a piece of land to the Town for use as an animal pound, but he kept the right to cut trees on it.

A large black boar, eight feet long, walked into town in November 1677. Almost every man in town gathered around it with his musket before they could capture it.

Mines and Minerals

By 1647, residents had found "plenty of iron and some lead" in the wilderness. Everyone was encouraged to look for more. The following year, John Dwight and Francis Chickering thought they had found a mine in what is now Wrentham. A decade later, in 1658, a committee was appointed to look into setting up an ironworks within the town. Neither the mine nor the ironwork turned out to be successful.

Other Notable Facts

Old Village Cemetery

The first part of the Old Village Cemetery was set aside at the first recorded meeting of Dedham's settlers on August 18, 1636. Land was taken from Nicholas Phillips and Joseph Kingsbury. It remained the only cemetery in Dedham for nearly 250 years until Brookdale Cemetery was established.

Early Records: A Town's Memory

Dedham is one of the few colonial towns that has kept extensive records from its earliest years. These records have been described as "very full and perfect." They are so detailed that a map of the first settlers' home lots can be drawn using only the descriptions in the book of grants. Many records come from Timothy Dwight, who served as town clerk for 10 years and selectman for 25.

In 1681, the town voted to collect all deeds and other writings and store them in a box kept by Deacon John Aldis to preserve them better. The records included four deeds from Native Americans at Petumtuck, one from Chief Nehoiden, one from Magus, and one deed and one receipt from King Phillip.

Jonathan Fairbanks and His House

In 1637, Jonathan Fairbanks signed the town Covenant. He was given 12 acres (4.9 ha) of land to build his home, which is now the oldest house in North America. In 1640, "the selectmen provided that Jonathan Fairbanks 'may have one cedar tree set out unto him to dispose of where he will: In consideration of some special service he hath done for the towne.'" He had hesitated to join the church due to some doubts about public faith. But after many friendly talks, he declared his faith and was gladly accepted by the whole church.

The house is still owned by the Fairbanks family and stands at 511 East Street. Jonathan Fairbanks has many notable descendants, including Presidents William H. Taft, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks. He is also an ancestor of the father and son Governors of Vermont, Erastus Fairbanks and Horace Fairbanks, the poet Emily Dickinson, and the anthropologist Margaret Mead.

Early Laws and Rules

In early years, each resident was told to keep a ladder handy. This was in case they needed to put out a fire on their thatched roof or climb to safety during an attack from Native Americans. It was also decided that if anyone tied their horse to the ladder against the meetinghouse, they would be fined sixpence. The Town sometimes had to fine people caught borrowing another's canoe without permission or cutting down trees on common land. A one-shilling fine was put in place in 1651 for taking a canoe without permission.

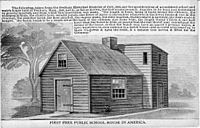

America's First Public School

On January 1, 1644, by a unanimous vote, Dedham authorized the first U.S. taxpayer-funded public school. It was called "the seed of American education." Its first teacher, Rev. Ralph Wheelock, was paid 20 pounds a year to teach the community's youth. Descendants of these students would become presidents of Dartmouth College, Yale University, and Harvard University. Another early teacher, Michael Metcalf, was one of the town's first residents and a signer of the Covenant. At age 70, he began teaching reading in the school.

John Thurston was hired by the town to build the first schoolhouse in 1648. He received a partial payment of £11.0.3 on December 2, 1650. The contract required him to build floorboards, doors, and fit the inside with "featheredged and rabbited" boarding, similar to what's found in the Fairbanks House.

Dedham's early residents were so dedicated to education that they donated £4.6.6 to Harvard College during its first eight years. This was more than many other towns, including Cambridge itself. By the later part of the century, however, a feeling against intellectualism spread through the town. Residents were content to let the minister be the local intellectual. They did not establish a grammar school as required by law. As a result, the town was called into court in 1675 and again in 1691.

Colonial Politics and Dedham's Role

When King Charles II threatened to take away the charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Dedham strongly opposed it. The Town Meeting asked Governor Simon Bradstreet to protect the colonists' rights and interests. In a unanimous vote, they also rejected a motion to completely submit to the king and accept his decision to revoke the charter.

Daniel Fisher and his sister Lydia helped hide William Goffe and Edward Whalley after they sought safety in America. During the 1689 Boston revolt, Fisher grabbed Governor Edmund Andros by the collar and arrested him. This was both to protect him from a mob and to ensure he faced trial.

A group of important clergy from around the colony, including Dedham's John Allin, wrote a petition to the General Court in 1671. They complained that lawmakers were causing anti-clerical feelings. They asked the General Court to support the clergy's authority in spiritual matters, which included the Half-Way Covenant. The General Court agreed, but 15 members, including Joshua Fisher and Daniel Fisher, disagreed.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |