Nipmuc facts for kids

portrait of Hepsibeth Hemenway, a Nipmuc woman from Worcester, Massachusetts, 1830

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Contemporary people claiming Nipmuc descent: 354 Chaubunagungamaug, (2002) 526 Hassanamisco Nipmuc (2004). Possible total 1,400 (2008) |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central Massachusetts ( |

|

| Languages | |

| English, possibly formerly Nipmuc and Massachusett, | |

| Religion | |

| Traditionally Animism (Manito), Christianity. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Narragansett, Shawomet, Pawtuxet, Eastern Niantic peoples |

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous group from the Northeastern Woodlands. They used to speak an Eastern Algonquian language. Their traditional homeland, called Nippenet, means "the freshwater pond place." It is located in central Massachusetts and parts of Connecticut and Rhode Island.

The Nipmuc people had some contact with European traders and fishermen before Europeans started settling the Americas. The first known meeting with Europeans happened in 1630. A Nipmuc man named John Acquittamaug sold corn to the hungry colonists in Boston, Massachusetts. The colonists brought diseases like smallpox, which Native Americans had no protection against. Many tribes in New England suffered greatly and died from these illnesses.

As colonists moved onto their land, made unfair land deals, and created laws to encourage more European settlement, many Nipmuc joined Metacomet's war. This war, known as King Philip's War, started in 1675 against colonial expansion. However, they could not defeat the colonists. Many Nipmuc were forced to live on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. There, many died from sickness and not enough food. Others were killed or sold into slavery in the West Indies.

A Christian missionary named John Eliot arrived in Boston in 1631. He learned the Massachusett language, which was widely understood in New England. He converted many Native Americans to Christianity. He also published a Bible translated into Massachusett and a Massachusett grammar book. With support from the colonial government, he set up several "Indian plantations" or praying towns. In these towns, Native Americans were encouraged to settle. They were taught European customs and converted to Christianity.

Today, the state of Massachusetts officially recognizes the Nipmuc Nation. However, the United States federal government does not.

Contents

Who are the Nipmuc People?

The Nipmuc tribe was first mentioned in a letter in 1631. Deputy Governor Thomas Dudley called them the Nipnet. This name means 'people of the freshwater pond' because they lived inland. Other versions of the name include Neipnett, Neepnet, and Nipneet.

In 1637, Roger Williams recorded the tribe as the Neepmuck. This comes from Nipamaug, meaning 'people of the freshwater fishing place'. Other spellings include Neetmock and Nipmaug. Colonists and Native Americans used this term often after the praying towns grew. French people called most New England Native Americans Loup, meaning 'the Wolf People'. But Nipmuc people who moved to French Colonial Canada and lived among the Abenaki called themselves ȣmiskanȣakȣiak. This means the 'beaver tail-hill people'.

Nipmuc Language and Culture

The Nipmuc people most likely spoke Loup A. This is a Southern New England Algonquian language. Today, efforts are being made to bring the language back. Several people are learning it as a second language. Ohketeau is a local group working on language revival.

Nipmuc Tribal Groups

Daniel Gookin, who helped Native Americans and worked with Eliot, carefully separated the Nipmuc (proper) from the Wabquasset, Quaboag, and Nashaway tribes. Native American groups were very independent. People who were unhappy with their leaders could join other groups. Also, alliances often changed based on family ties, military needs, and relationships with other tribes.

The creation of the praying towns changed some tribal divisions. Native Americans from different areas settled together. Four groups linked to the Nipmuc people exist today:

- Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck, also known as Dudley Indians.

- These are descendants of the Praying town of Chaunbunagungamaug. This area is now part of Webster. Their lands were returned by the town of Dudley, Massachusetts. The tribe's reservation is 2.5 acres in Dudley. Their office is there, and it also crosses into Thompson, Connecticut.

- Hassanamisco Nipmuc, also known as Grafton Indians.

- These are descendants of the Praying town of Hassanamessit. This area is now part of Grafton, Massachusetts. The Cisco (Scisco, Ciscoe) family kept their four acres from the last Hassamessit land sales. This land serves as their current reservation.

- Natick Massachusett, also known as Natick Nipmuc.

- The descendants of the Praying town of Natick, Massachusetts do not have any of their original lands left. The Natick people are mainly descended from the Massachusett tribe, but they also have Nipmuc ancestors. They can receive state services as Nipmuc.

- Connecticut Nipmuc.

- These are descendants of various Nipmuc people who survived or moved to Connecticut. The Nipmuc of Connecticut are not recognized by the state.

Legal Status of the Nipmuc People

State Recognition in Massachusetts

In 1976, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued Executive Order #126. This order stated that 'State agencies shall deal directly with ... [the] Nipmuc ... on matters affecting the Nipmuc Tribe'. It also called for a state 'Commission on Indian Affairs'. This all-Indian Commission was created. It provided state support for education, health care, cultural preservation, and protection of remaining lands for the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Massachusett tribes.

The state also requires that all human remains found during construction or other projects be examined. The Commission must be notified. After investigation by the State Archaeologist, they decide what to do.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts also recognized the Nipmuc(k) tribe's connection to the historic tribe. It praised their efforts to keep their culture and traditions alive. The state also officially canceled the General Court Act of 1675. This law had banned Native Americans from Boston during King Philip's War. The tribe also works closely with the state on archaeological digs and preservation projects. The tribe, along with the National Congress of American Indians, opposed building a sewage treatment plant on Deer Island in Boston Harbor. Many burial sites were disturbed by its construction. Each year, the tribe holds a remembrance service for members lost during the winter on Deer Island during King Philip's War. They also protest against the destruction of Native American burial sites.

Efforts for Federal Recognition

On April 22, 1980, Zara Cisco Brough, who owned land in Hassanamessit, sent a letter. She wanted to officially ask for federal recognition as a Native American tribe.

On July 20, 1984, the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) received the official request. It was from the 'Nipmuc Tribal Council Federal Recognition Committee'. Zara Cisco Brough and her successor, Walter A. Vickers, from Hassanamisco, signed it. Edwin 'Wise Owl' W. Morse, Sr. from Chaubunagungamaug also signed. In January 2001, the BIA made a first decision in favor of the Nipmuc Nation of Sutton, Massachusetts. Most of its members lived in Massachusetts. However, a negative first decision was made for the Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck Band of Dudley, Massachusetts. Its members were split almost evenly between Massachusetts and Connecticut. In 2004, the BIA told the Nipmuc Nation that their request for federal recognition was denied.

Nipmuc History in Colonial Times

The 17th Century

Sailors, fishermen, and adventurers from Europe started visiting New England in the early modern period. The first permanent settlements in the area began after Plymouth Colony was founded in 1620. These early visitors brought several infectious diseases. Native Americans had never been exposed to these diseases before. This led to epidemics where up to 90 percent of the population died. Smallpox killed many Native Americans in 1617–1619, 1633, 1648–1649, and 1666. Also, influenza, typhus, and measles affected Native Americans throughout this time. In 2010, researchers suggested a new idea. The epidemics between 1616 and 1619 might have been caused by leptospirosis, a serious bacterial disease.

Writings from people like Increase Mather show that colonists believed God was helping them. They thought God was clearing the new lands for settlement by causing the Native American population to shrink. At the time of contact, the Nipmuc were a fairly large group. They were under the protection of stronger neighbors. These neighbors protected them, especially from raiding tribes like the Pequot, Mohawk, and Abenaki.

At first, the colonists relied on Native Americans to survive in the New World. Native Americans quickly began trading their food, furs, and wampum. In return, they received copper kettles, weapons, and metal tools from the colonists. Many Puritan settlers arrived from 1620–1640 during the 'Great Migration'. This increased their need for more land. Since the colonists had different land grants from the colony and the king, they needed Native American names on land deeds to make them seem legal. This process had problems. For example, John Wompas signed over many lands to the colonists to gain favor, even lands that weren't his.

Indian Plantations (Praying Towns)

The royal charter for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 called for converting Native Americans to Christianity. The colonists did not seriously start this work until after the Pequot War. This war showed their military strength. They gained official support in 1644.

Many Native Americans responded to the call. The Reverend John Eliot learned the Massachusett language from tribal interpreters. He created an Indian Bible and a grammar book for the language. This language was well understood from Cape Ann to Connecticut. Colonial authorities also supported settling Native Americans in 'Indian plantations' or Praying towns. In these towns, Native Americans were taught European farming methods, culture, and language. Indian preachers and councilors, often from important native families, managed these towns. Native Americans blended their own culture with European culture. However, they were mistrusted by both the colonists and their non-converted relatives. The colonists and later state governments slowly sold off these plantations. By the late 1800s, only the Cisco family home in Grafton was still owned by direct descendants of Nipmuc landowners.

Here is a list of Indian Plantations (Praying towns) connected to the Nipmuc:

- Chaubunagungamaug, Chabanakongkomuk, Chaubunakongkomun, or Chaubunakongamaug

- Meaning: 'The boundary fishing place,' or 'at the boundary.'

- Location: Webster, Massachusetts (on lands given from Dudley).

- Hassanamesit, Hassannamessit, Hassanameset, or Hassanemasset

- Meaning: 'Place where there is [much] gravel,' or 'at a place of small stones.'

- Location: Grafton, Massachusetts.

- Makunkokoag, Magunkahquog, Magunkook, Maggukaquog, or Mawonkkomuk

- Meaning: 'Place of great trees,' or 'place that is a gift.'

- Location: Hopkinton, Massachusetts.

- Manchaug, Manchauge, Mauchage, Mauchaug, or Mônuhchogok

- Meaning: 'Place of departure,' or 'island of rushes.'

- Location: Sutton, Massachusetts.

- Manexit, Maanexit, Mayanexit

- Meaning: 'Where the road lies,' or 'near the path.'

- Location: Thompson, Connecticut.

- Nashoba

- Meaning: 'The place between' or 'between waters.'

- Location: Littleton, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Pennacook.

- Natick

- Meaning: 'Place of hills.'

- Location: Natick, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Massachusett.

- Okommakamesitt, Agoganquameset, Ockoocangansett, Ogkoonhquonkames, Ognonikongquamesit, or Okkomkonimset

- Meaning: 'Plowed field place' or 'at the plantation.'

- Location: Marlborough, Massachusetts.

- Packachoag, Packachoog, Packachaug, Pakachog, or Packachooge

- Meaning: 'At the turning place,' or 'bare mountain place.'

- Location: Auburn, Massachusetts.

- Quabaug, Quaboag, Squaboag

- Meaning: 'Red pond,' or 'pond before.'

- Location: Brookfield, Massachusetts.

- Quinnetusset, Quanatusset, Quantiske, Quantisset, or Quatiske, Quattissick

- Meaning: 'Long brook' or 'little long river.'

- Location: Thompson, Connecticut.

- Wabaquasset, Wabaquassit, Wabaquassuck, Wabasquassuck, Wabquisset or Wahbuquoshish

- Meaning: 'Mats for covering a lodge,' or 'place of white stones.'

- Location: Woodstock, Connecticut.

- Wacuntuc, Wacantuck, Wacumtaug, Wacumtung, Waentg, or Wayunkeke

- Meaning: 'A bend in the river.'

- Location: Uxbridge, Massachusetts. Originally Mendon, Massachusetts, sold by Nipmuck as "Squnshepauk" Plantation.

- Washacum or Washakim

- Meaning: 'Surface of the sea.'

- Location: Sterling, Massachusetts.

- Also settled by the Pennacook.

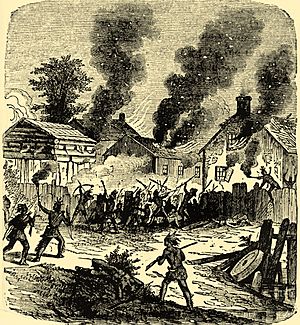

King Philip's War (1675-1676)

The Massachusetts Bay Colony passed many laws against Native American culture and religion. New laws limited the influence of powwows, or 'shamans'. They also restricted non-converted Native Americans from entering colonial towns on the Sabbath. The Nipmuc were also told that any undeveloped lands could be taken by the growing colony. These harsh rules and the increasing loss of land led many Nipmuc to join the Wampanoag chief Metacomet. His war against colonial expansion, known as King Philip's War, affected New England from 1675 to 1676.

Native Americans who had already settled in the Praying towns were forced to live on Deer Island in Boston Harbor during the winter. Many died there from starvation and cold. Although many Native Americans fled to join the uprising, others joined the colonists. The Praying Indians were especially at risk. The war made all Native Americans seem suspicious. But the Praying towns were also attacked by the 'wild' Native Americans who joined Metacomet's fight. The Nipmuc were major participants in the sieges of Lancaster, Brookfield, Sudbury, and Bloody Brook, all in Massachusetts. The tribe prepared well for conflict by forming alliances. They even had "an experienced gunsmith, a lame man, who kept their weapons in good working order." The siege of Lancaster also led to the capture of Mary Rowlandson. She was held captive until she was ransomed for £20. She later wrote a book about her experience. The Native Americans lost the war. Survivors were hunted down, killed, sold into slavery in the West Indies, or forced to leave the area.

The 18th Century

The Nipmuc regrouped around their former Praying towns. They managed to keep some independence. They used their remaining lands for farming or selling timber. The tribe's population decreased due to several smallpox outbreaks in 1702, 1721, 1730, 1752, 1764, 1776, and 1792. Land sales continued steadily. Much of the money from these sales went to legal fees, personal expenses, and improvements to the reserve lands. By 1727, Hassanamisset was reduced to 500 acres from its original 7,500 acres. That land became part of Grafton, Massachusetts. In 1797, the Chaubunagungamaug Reserve was reduced to 26 acres from 200.

The shift to raising cattle also hurt the native economy. The colonists' cattle ate the unfenced lands of the Nipmuc. Courts did not always side with the Native Americans. However, Native Americans quickly started raising swine (pigs). This was because changes in the economy and loss of untouched lands reduced their ability to hunt and fish. Since Native Americans had few assets besides land, much of it was sold to pay for medical, legal, and personal costs. This increased the number of Native Americans without land. With fewer people and less land, Native American independence slowly disappeared by the time of the Revolutionary War. The remaining reserve lands were overseen by guardians appointed by the colony and later the state. These guardians were supposed to act on behalf of the Native Americans. However, the Hassanamisco guardian Stephen Maynard, appointed in 1776, stole funds and was never punished.

Wars and Emigration

New England quickly became involved in a series of wars between the French and British and their Native American allies. Many Native Americans from New England who had left the region joined the Abenaki, who were allied with the French. However, local Native Americans were often forced to serve as guides or scouts for the colonists. Wars took up much of the century. These included King William's War (1689–1699), Queen Anne's War (1704–1713), Dummer's War (1722–1724), King George's War (1744–1748), and the French and Indian War (1754–1760). Many Native Americans also died serving in the Revolutionary War.

The chaos of the Indian Wars and growing mistrust of Native Americans by colonists led to a steady movement of people. Sometimes, entire villages fled to mixed-tribe groups. They went north to the Pennacook and Abenaki, who were protected by the French. Or they went west to join the Mahican at growing mixed settlements like Schagticoke or Stockbridge. The Stockbridge group eventually moved as far west as Wisconsin. This further reduced the Native American presence in New England, though not all Native Americans left. Those Nipmuc who fled eventually blended into the main host tribe or the new mixed groups that formed.

Modern Nipmuc History

The 19th Century

Native Americans became wards of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. This meant they were represented by non-Native guardians appointed by the state. Fast cultural blending and intermarriage made many people believe the Nipmuc had simply disappeared. This was partly due to old ideas about Native Americans and to justify colonial expansion. Native Americans continued to exist, but fewer and fewer could live on the shrinking reserve lands. Most left to find work as house servants or laborers in white homes. Some went to sea as whalers or sailors. Others moved to growing cities to work as laborers or barbers.

Growing cultural blending, intermarriage, and shrinking populations led to the loss of the Natick Dialect of the Massachusett language. By 1798, only one speaker could be found. One cultural practice that survived was selling handmade, square-edged splint baskets and traditional medicines. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts investigated the condition of Native Americans. It decided to grant them citizenship with the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869. This law eventually led to the sale of any remaining lands. Hassanamessit was divided among a few families. In 1897, the last of the Dudley lands were sold. The remaining Native Americans were housed in the poor house on Lake Street in Webster, Massachusetts.

Intermarriage and Censuses

Intermarriage between White, Black (or Chikitis), and Native American people began early in colonial times. Africans and Native Americans had a similar imbalance in gender. Slave traders brought few enslaved African women to New England. Many Native American men died in war or joined the whaling industry. So, many Native American women married African men. Marriage with white people was uncommon due to colonial laws against marriage between different races. The children of these marriages were accepted into the tribe as Native Americans. This was because Nipmuc culture focused on the mother's side of the family. However, to their skeptical white neighbors, their increasingly Black appearance made some people doubt their Native American identity. By the 1800s, only a few "pure-blood" Native Americans remained. Native Americans disappeared from state and federal census records. Instead, they were listed as 'Black', 'mulatto', 'colored', or 'miscellaneous' depending on their appearance.

In 1848, the Massachusetts Senate Joint Committee on Claims asked for a report on several tribes receiving state aid. Three reports were made: The 1848 'Denney Report'; the 1849 'Briggs Report'; and the 1859 'Earle Report'. Each report was more detailed than the last. To be recognized as Nipmuc, people needed to have an ancestor listed on these reports or on lists of funds from Nipmuc land sales. These lists did not count all Native Americans. Many Native Americans may have been well-integrated into other racial communities. Also, Native Americans moved frequently.

| Massachusetts 'Indian Censuses' | Dudley Indians | Dudley Surnames | Grafton Indians | Grafton Surnames |

| 1848, Denney Report | 51 | 2 | ||

| 1849, Briggs Report | 46 | Belden, Bowman, Daly, Freeman, Hall, Humphrey, Jaha, Kile (Kyle), Newton, Nichols, Pichens (Pegan), Robins, Shelby, Sprague and Willard. | 26 | Arnold, Cisco, Gimba (Gimby), Heeter (Hector) and Walker. |

| 1861, Earle Report | 77 | Bakeman, Beaumont, Belden, Cady, Corbin, Daley, Dorus, Esau, Fiske, Freeman, Henry, Hull, Humphrey, Jaha, Kyle, Nichols, Oliver, Pegan, Robinson, Shelley, Sprague, White, Willard and Williard. | 66 | Arnold, Brown, Cisco, Gigger, Hazard, Hector, Hemenway, Howard, Johnson, Murdock, Stebbins, Walker and Wheeler. |

- Some ancestors were recorded as 'colored'. This included people from the Brown, Cisco, Freeman, Gigger, Hemenway, Hull, Humphrey, Walker, and Willard families.

- Some Gigger family members were called 'miscellaneous Indians.'

- Some individuals were recorded as 'mixed'. This included people in the Bakeman, Belden, Brown, Kyle, and Hector families.

- Some people from the Hall, Hector, and Hemenway families had no label.

The 20th and 21st Centuries

Local views on Native American culture and history changed. This was due to collectors of old items, anthropologists, groups like the Boy Scouts of America, and the 1907 appearance of Buffalo Bill Cody. He brought many Native Americans in feathered headdresses to pay respects to Uncas, a chief of the Mohegan tribe. Despite almost 400 years of cultural blending and the loss of economic and community support, some Native American families kept a distinct identity.

The turn of the century also saw active cultural and family history research. James L. Cisco and his daughter Sara Cisco Sullivan from the Grafton homestead worked on this. They worked closely with members of other related tribes. These included Gladys Tantaquidgeon and the Fielding families of the Mohegan Tribe, Atwood L. Williams of the Pequot, and William L. Wilcox of the Narragansett. Together, various tribal members began sharing cultural memories. The idea of pan-Indianism (unity among Native American tribes) took hold in the 1920s. Indian gatherings like the Algonquin Indian Council of New England met in Providence, Rhode Island. Dances or powwows were held, such as those at Hassanamessit in 1924. Plains Indian clothing was often worn to show Native American identity. It also proved their continued presence in the area, as much of the original culture had been lost. Other Nipmuc individuals appeared at town events and fairs. This included the 1938 appearance at the Sturbridge, Massachusetts bicentennial fair of many ancestors of today's Chaubunagungamaug Nipmuck.

By the 1970s, the Nipmuc had made great progress. Many local tribe members were asked to help develop the Native American exhibit at Old Sturbridge Village. This is a 19th-century living museum built in the heart of former Nipmuc territory. State recognition was also achieved by the end of the same decade. This re-established the Nipmuc people's relationship with the state and provided some social services. The Nipmuc sought federal recognition in the 1980s.

Tension between the Nipmuc Nation and the rest of the Chaubunagungamaug tribe caused a split in the mid-1990s. The Nipmuc Nation included the Hassanamisco and many descendants of the Chaubunagungamaug, based in Sutton, Massachusetts. The other part of the Chaubunagungamaug was based in Webster, Massachusetts. The split was caused by frustration with the slow pace of recognition and disagreements about gambling.

Land, 190 acres, in the Hassanamessit Woods in Grafton, was planned for development with over 100 homes. This property is believed to contain the remains of the old praying village. It has great cultural importance to the Nipmuc Tribal Nation. However, The Trust for Public Land, the town of Grafton, the Grafton Land Trust, the Nipmuc Nation, and the state of Massachusetts stepped in. The Trust for Public Land bought the property and kept it off the market until 2004. This was after enough money was raised to protect the property permanently. The property is also important for its environment. It is next to 187 acres of Grafton-owned land and 63 acres owned by the Grafton Land Trust. These properties will offer many recreational benefits to the public. They will also help protect the water quality of local rivers and streams.

In July 2013, the Hassanamisco band chose a new chief, Cheryll Toney Holley. She took over after Walter Vickers resigned.

See also

In Spanish: Nipmuck para niños

In Spanish: Nipmuck para niños