Massachusett facts for kids

|

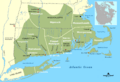

Location of the Massachusett and related peoples of southern New England.

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Massachusett language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Puritanism), Indigenous religion , traditionally Algonquian traditional religion. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nipmuc, Wampanoag, Narraganasett, Mohegan, Pequot, Pocomtuc, Montaukett and other Algonquian peoples |

The Massachusett were a Native American tribe who lived in the area around what is now Greater Boston in Massachusetts. Their name comes from the Massachusett language and means "At the Great Hill." This refers to the Blue Hills, which are hills overlooking Boston Harbor from the south.

The Massachusett people were among the first Native Americans in New England to meet European explorers. Sadly, many of them died from diseases like leptospirosis around 1619. This disease killed up to 90 percent of the people in coastal areas. More diseases like smallpox and influenza followed, which Native people had no natural protection against. Because so many Massachusett people died, they were too few to stop English colonists from taking over their fertile coastal lands.

A missionary named John Eliot helped many Massachusett people become Christians. He created special communities called praying towns. In these towns, Native Americans were expected to follow colonial laws and adopt European customs, but they could still use their own language. Eliot learned the Massachusett language and even translated the Bible into it. However, the Massachusett language slowly disappeared and was no longer the main language by the 1750s. It likely died out completely by the early 1800s.

By the early 1800s, the last of the Massachusett's shared lands were sold. This weakened the community ties that held Massachusett families together. Most Massachusett people had to live among their European American neighbors. They often settled in poorer parts of towns, living separately with Black Americans, new immigrants, and other Native Americans. The Massachusett people who survived eventually blended into the surrounding communities.

Contents

- What's in a Name?

- Where Did They Live?

- How Were They Organized?

- Massachusett Language

- How They Lived and Ate

- Massachusett History

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name?

Massachusett: The Tribe's Own Name

The Massachusett people called themselves Massachuseuck. This name means "at the great hill." It refers to the Great Blue Hill, which is located in Ponkapoag.

How Others Called Them

English settlers started using the name Massachusett for the people, their language, and eventually for their colony, which became the state of Massachusetts. John Smith first wrote about the term Massachusett in 1616. The Narragansett people called the tribe Massachêuck.

Where Did They Live?

The Massachusett people historically lived on the hilly, forested, and fertile coastal plain along the southern side of Massachusetts Bay. This area is now eastern Massachusetts. Important rivers in their territory included the Charles River and the Neponset River.

The Pennacook tribe lived north of the Massachusett. The Nipmuc were to the west, the Narragansett to the southwest in Rhode Island, and the Wampanoag (formerly Pokanoket) to the south. One expert, John R. Swanton, believed their land stretched as far north as Salem, Massachusetts, and south to Marshfield and Brockton.

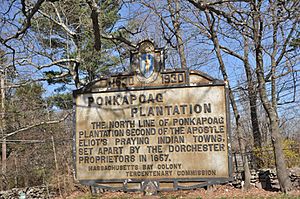

By the 1660s, many Massachusett people moved into praying towns like Natick and Ponkapoag (Canton).

Here are some places where Massachusett settlements were located:

- Conohasset, Cohasset

- Cowate, praying town, Charles River falls

- Magaehnak, six miles from Sudbury

- Massachuset, Blue Hills Reservation, on the border of Milton, Canton, Randolph and Quincy

- Mishawum, Charlestown, Boston

- Mystic, Medford

- Nahapassumkeck, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Natick, Praying town

- Neponset, on Neponset River near Stoughton

- Nonantum, Newton

- Pequimmit, praying town, Stoughton

- Pocapawmet, South Shore

- Punkapog, praying town, Canton

- Saugus, near Lynn

- Seccasaw, northern part of Plymouth County

- Titicut, praying town, possibly Wampanoag, Middleborough

- Topeent, northern coast of Plymouth County

- Toant, in or near Boston

- Unquatiquisset, Milton and Lower Mills

- Wessagusset, near Weymouth

- Winnisimmet, Chelsea

- Wonasquam, near Annisquam

How Were They Organized?

The Massachusett people lived in villages, which were part of larger groups called bands. These bands were often named after their sachems or leaders.

Some of the major bands and their leaders included:

- Chickatawbut: His territory was south of the Charles River. His son Wompatuck later led this band.

- Nanepashemet: His land was divided among his three sons:

* Winnepurkit: Around Deer Island and Boston Harbor. * Wonohaquaham: In Winnisimmet and Saugus. * Montowampate: In Massebequash and Lynn.

- Manatahqua: Lived around Nahant and Swampscott.

- Cato: Lived east of the Concord River.

- Nahaton: Lived around Natick.

- Cutshamekin: Lived around Dorchester, Sudbury, and Milton.

By 1743, guardians were appointed to manage the affairs of the Praying Indians. This ended the power of the local chiefs and the traditional way the Massachusett tribe was organized.

Massachusett Language

The Massachusett language was very important in New England. It was also spoken by the Wampanoag, Nauset, Cowesset, and Pawtucket people. Because it was similar to other languages in the area, a simpler version, a pidgin, was used for trade and talking between different tribes.

By the 1750s, Massachusett was no longer the main language in the community. By 1798, only one very old Massachusett person in Natick still spoke it. Many things caused the language to disappear. People married non-Native speakers, they needed English for jobs, and the language was not seen as important. Also, Native communities broke apart, and people moved away, making it harder for speakers to connect. The Wampanoag on Noepe kept the language longer, until the 1890s, because they had more secure land and a larger population.

How They Lived and Ate

The Massachusett people lived on fertile, flat lands. Men and women worked together to clear fields for farming. Women grew food crops like northern flint corn, different kinds of beans, squashes, and pumpkins. They planted corn in mounds, then planted beans to grow up the cornstalks. Finally, they planted squash plants, which protected the roots and kept weeds away. This method is called the Three Sisters.

They also gathered other plants like grapes, strawberries, blackberries, and different kinds of nuts.

Massachusett people lived in villages along rivers for part of the year. Families lived in dome-shaped houses called wétu. These houses had curved wooden frames covered with woven mats in winter or bark in summer. Inside, they stored their belongings in bags and baskets. Men carved wooden bowls and spoons for eating.

For water travel, they used both carved dugout canoes and birchbark canoes.

Massachusett History

Early European Encounters

The first known meeting with Europeans might have been in 1605. French explorer Samuel de Champlain arrived in Boston Harbor. Champlain met Massachusett leaders on some of the Boston Harbor Islands and traded with them. He had an Algonquin guide and his Massachusett-speaking wife to help translate. Champlain mapped the area, but the large Native population and their resistance made the French less interested in settling there. Later, John Smith mapped the region as "New England." He also landed at Wessagusset and Conohasset, where he traded and met chiefs, which encouraged more English settlement.

Diseases and Their Impact

As more European fishermen, explorers, and traders came, the Massachusett and nearby tribes suffered greatly from diseases. Native peoples had not been exposed to many diseases carried by Europeans and their animals, so they had no protection. These new diseases quickly caused many virgin soil epidemics that wiped out large numbers of people.

A deadly epidemic from 1616 to 1619, possibly leptospirosis, killed between 33 and 90 percent of the Native American population in New England. The Massachusetts smallpox epidemic of 1633 further reduced Native populations. Smallpox outbreaks continued almost every decade. These diseases and the arrival of Europeans changed the power balance among New England tribes.

Relations with Plymouth Colony (1620–1626)

English settlers, known as Pilgrims, started their first permanent settlement in New England at Plymouth Colony in 1620. This was near a former Wampanoag village, just south of Massachusett land. In 1621, the Pilgrims met Obbatinewat, a local Wampanoag leader. They signed a peace treaty with him, and he introduced them to the Squaw Sachem of Mistick, a Massachusett leader.

The Wampanoag war chief Massasoit decided to become friends with the Pilgrims. The Pilgrims also met Chickatawbut, the most powerful Massachusett leader at the time. Unlike Massasoit, who wanted to work with the English against other tribes, Chickatawbut and other Massachusett leaders were careful about the new settlers.

Chickatawbut's worries came true when the Plymouth Colony expanded into Massachusett territory at Wessagusset. The new settlers were not prepared and soon started raiding Massachusett villages for food. To stop a bigger conflict, Pilgrim leader Myles Standish attacked in 1624. This led to the deaths of Massachusett warriors like Pecksuot and Wituwamat, who were tricked into meeting the Pilgrims under the promise of peace. Standish also angered the Massachusett when he broke up a settlement of English settlers at Merrymount, where they were drinking and gambling with Massachusett women. These events caused the Massachusett to stop trading with the Pilgrims for many years.

Relations with Massachusetts Bay Colony (1629-1676)

The Massachusett people could not avoid the English settlers. Even after stopping relations with the Pilgrims, more English settlers, mostly Puritans, began to arrive. They first settled in Wonnisquam in 1623 and later expanded to Naumkeag. In 1628, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was officially created, claiming land north of Plymouth Colony. The border between the two colonies was similar to the traditional border between the Massachusett and Wampanoag.

Massachusett leaders sometimes gave land deeds to English settlers. Often, this was because the land was already empty due to disease. The leaders would sell land, sometimes with rules allowing Native people to still gather food or fish. However, the English settlers rarely honored these agreements. The settlers also thought they were buying land permanently, while Native people often saw it as leasing. Because of this fast loss of land, Massachusett leaders went to Boston in 1644 to sign the Acts of Submission. This put Native people under the control of the colonial government and its laws, and opened them to Christian missionaries. By this time, the Massachusett, who lived by the coast, had lost access to their shellfish gathering sites.

Population Changes

Native peoples in New England faced growing pressure as English settlers arrived. In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony grew a lot with the arrival of the Winthrop Fleet, bringing almost a thousand colonists. This started the "Great Migration." By 1640, the colonial population had more than doubled to almost twenty thousand.

The settlers were worried about the Native presence, as Native people were still the majority when all groups were counted. Native populations continued to drop due to diseases like scarlet fever, typhus, measles, mumps, influenza, and smallpox. A smallpox epidemic in 1633 and 1634 was especially bad, affecting people far inland. The Massachusett population fell to fewer than two thousand people. Other epidemics happened in 1648 and 1666. With so many areas empty, English settlers believed that God had cleared the land for them. By the 1630s, Native people in New England were already a minority in their own lands.

The Massachusett offered little armed resistance to colonial settlement. Other Native peoples were defeated after the Pequot War ended in 1638. This war led to massacres of Pequot non-fighters, like the Mystic Massacre, and many Native people were sold into slavery. The war destroyed the Pequot as a tribe, opening up more land in New England for colonial settlement.

Becoming Christian

The original plan for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628 was to "win and invite the Natives of Country, to the Knowledge and Obedience of the only true God." At first, the colonists were focused on surviving. But when missionary John Eliot, known as the "Apostle to the Indians," arrived and had success, colonial leaders started to support the effort more. Eliot learned the Massachusett language with the help of two Native servants who spoke English. Once he felt ready, Eliot tried to preach to the Neponset tribe in 1646 but was turned away. Later, he had better success with the Nonantum tribe led by Waban, and Waban and most of his tribe became Christians.

Native people had mixed reactions to Christianity. Many leaders were still wary of English settlers and wanted their people to keep their traditions. But many others fully accepted the new religion. Those who converted often did so because their traditional healers, called powwow (pawâwak), could not protect them from settlers taking their land or from new diseases. These Native people hoped the settlers' God would protect them. Others likely converted because they felt they had to. The colonial government had forced tribal leaders to sign the 1644 Acts of Submission, which made them accept colonial authority and missionary work. Many leaders were probably still afraid after the Pequot War. Some converted hoping to improve relations with settlers. However, Puritans often still mistreated Native people and doubted their sincerity, calling the new believers "Praying Indians."

Praying Towns (1651–1675)

Eliot encouraged the newly converted Massachusett people to settle near the Quinobequin River. However, they were immediately sued by settlers from Dorchester who claimed the land. By the time Eliot started his mission, the Massachusett had lost access to their coastal shellfishing areas and were losing most of their hunting and foraging lands. Eliot asked the General Court to set aside land grants for Native people "forever." Natick was founded in 1651, followed by Ponkapoag in 1654. Thirteen more settlements were created, mostly in Nipmuc areas. These communities, settled by Praying Indians, became known as "Praying towns." Ponkapoag had 60 residents, including Massachusett people, in 1674.

Praying towns helped with Christianization and adopting European customs. It was easier to give out Eliot's Massachusett-language Bibles and other books. Residents had to follow rules that forbid Native customs like cracking lice between teeth and encouraged farming by men, Puritan modesty, and hairstyles. For the colonial government, these towns brought Native people fully under the control of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Traditional Native leaders kept some power by becoming administrators, teachers, and tax collectors.

The Massachusett benefited from having clear ownership of common land where they could farm, hunt, and gather. This likely attracted more converts, as Praying towns were safe zones away from constant land demands and harassment. The Massachusett also regained some of their earlier importance. Many Praying towns were started by Native missionaries from Natick's powerful families, which earned them respect. The Massachusett language spread and became the language of reading, prayer, and government. This was helped by its historical use as a regional trade language and its use in the Bible translation.

Life in Praying towns was a mix of European and Native customs. Native people had to adopt Puritan habits of modesty, hairstyle, and dress. They were encouraged to learn European skills like woodworking, carpentry, and farming. Natick had its own Christian church, but services were held in Massachusett with Native preachers and drumming. Praying Indians kept many parts of their culture, like their traditional food and hunting, but blended them with the European culture and Christian religion they were forced to adopt. These towns were in many ways an early form of the Indian Reservations that came later.

Hard Times for Native People

The peace between English settlers and local Native peoples was tested. When Native chiefs accepted colonial rule and Christianity, it allowed them to use the colonial legal system. The Praying Indians of Natick were sued several times by English settlers claiming their land, but with Eliot's help, most of these attempts failed. However, Native people often lost in court. Some Native interpreters and chiefs gave up land to gain favor with settlers, even if they didn't have the right to sell it. For example, the Pawtucket leader Wenepoykin tried many times to get back lands lost during the 1633 epidemic, but his cases were dismissed.

King Philip's War (1675-1676)

King Philip's War, from 1675 to 1676, was terrible for both Native people and English colonists. By the early 1670s, leaders like Waban and Cutshamekin warned of growing anger among inland tribes like the Nipmuc. However, the war began with the Wampanoag leader Metacomet, also known as King Philip. He was the son of Massasoit, who had been friends with the Pilgrims. Metacomet tried to keep the peace, but he became angry after endless demands for land. The execution of his brother Wamsutta for selling land was a turning point. Metacomet then killed his interpreter, the Massachusett John Sassamon, and gathered support from other unhappy tribes. The war began with a raid on Swansea in June 1675. Metacomet united the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and other peoples. They attacked many English settlements, causing settlers to flee. The settlers quickly fought back, leading to more conflict.

The Massachusett, who were all Praying Indians living in Praying towns, stayed neutral during the war but suffered greatly. They were attacked in their fields and harassed by panicked English settlers who had strong anti-Native feelings. Metacomet's forces also targeted Praying towns, raiding for supplies and forcing or persuading people to join the fight. To calm the settlers, the Praying Indians agreed to stay in their towns, follow curfews, accept more supervision, and give up their weapons.

As the war continued, settlers decided to use some Praying Indians as scouts and guides in the colonial army. A group of Praying Indians, including many Massachusett, fought against Metacomet's warriors. Metacomet was eventually killed.

Guardianship of Native People

Instead of Native people simply becoming part of the mostly European region, the colony appointed officials called commissioners to oversee them. This started with the Natick in 1743 and later included all remaining tribes. At first, commissioners managed timber resources on Native lands, which were valuable. Soon, the guardian of Natick controlled land sales and any money from selling Native products, mostly land. As guardians gained more power and were rarely watched, there were many cases of questionable land sales and misuse of funds. The appointment of guardians made Native people like colonial "wards," meaning they could no longer directly go to court or vote in town elections. It also took away the power of Native chiefs.

The loss of land continued. As forests were cut down, Native people could no longer move seasonally or make a living from the land, forcing many into poverty. Land was their only valuable possession. Guardians often sold land to pay for medical care, orphans, or debts Native people owed. Native people were also victims of unfair credit schemes that often took their land. Without land to farm or gather food, Native people had to find jobs and settle in separate parts of cities.

The 1800s

Most of the lands set aside "forever" for Native peoples had been taken. What was left was a mix of a few common lands, individual plots, leased lands, and many colonial landowners living among Native families.

Even after tribal lands were gone, the restrictions of the guardians remained. As wards of the colonial and later state government, Native people could not vote in local elections or go to court on their own. Some Native people received yearly payments from funds created by land sales or by guardians for their support. However, guardians no longer had to keep careful lists of Native people, which had been used to separate them from non-Native people, especially as intermarriage increased.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts ordered reports on the condition of Native people. The Briggs Report (1849) did not mention the Massachusett or the Praying Town of Natick, where Massachusett people had joined.

John Milton Earle wrote a much more detailed report in 1859, published in 1861. Earle wrote that the Natick Tribe was almost gone, with only two families left, totaling twelve people. He noted they had no common lands left and suggested their remaining money be divided among these two families. Earle also observed that some Natick descendants had joined the Nipmuc people.

The 1900s and 2000s

For 105 years, between 1869 and 1974, there are very few records about the Massachusett people. In 1928, anthropologist Frank G. Speck published a book that included 17th-century Massachusett history. At Ponkapoag, Speck met Mrs. Chapelle (who died in 1919), who identified as a Massachusett Indian. Speck estimated that in 1921, about a dozen Massachusett and Narragansett descendants of the Ponkapoag praying town lived in what is now Canton.

Today, several groups claim to be descended from the historical Massachusett peoples. However, these groups are unrecognized, meaning they are not officially recognized by the federal or state governments.

Images for kids

-

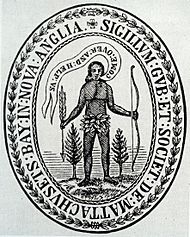

Original seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony depicting a Massachusett Indian proclaiming "Come over and help us"—a plea for conversion—inspired from Acts 16:19. Many contemporary Massachusett support initiatives to replace the Great Seal of Massachusetts which preserves most elements of the colonial original and has long been held offensive to many of the Native groups of the region.

See also

In Spanish: Massachusett (tribu) para niños

In Spanish: Massachusett (tribu) para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |