History of Guyana facts for kids

The history of Guyana started about 35,000 years ago when people first arrived from Eurasia. These early travelers became the Carib and Arawak tribes. They met the first Spanish explorers led by Alonso de Ojeda in 1499 at the Essequibo River. During the time of colonization, Guyana was ruled by the Spanish, French, Dutch, and British.

In the colonial period, Guyana's economy relied on large farms called plantations. These farms first used enslaved people for labor. There were big slave rebellions in 1763 and again in 1823. Great Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which ended slavery in most British colonies. This law freed over 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa. Slavery officially ended in British Guiana on August 1, 1834.

After slavery ended, plantations needed new workers. They brought in workers from India who signed contracts to work for a certain time. These Indian workers later joined with the descendants of enslaved Africans to demand equal rights. The Ruimveldt Riots in 1905 showed how strong these demands were. After World War II, the British Empire decided to let its colonies become independent. British Guiana gained its independence on May 26, 1966.

After independence, Forbes Burnham became the leader. He quickly became an authoritarian leader who wanted to bring socialism to Guyana. His power started to weaken after the Jonestown massacres in 1978, which brought international attention to Guyana. When he died unexpectedly in 1985, power was peacefully given to Desmond Hoyte. Hoyte made some democratic changes before he was voted out of office in 1992.

Contents

Early People and First Meetings

The first people in Guyana came from Siberia, possibly as long as 20,000 years ago. These early people were nomads, meaning they moved around a lot. They slowly traveled south into Central and South America. When Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas, Guyana's people were split into two main groups. The Arawak lived along the coast, and the Carib lived further inland.

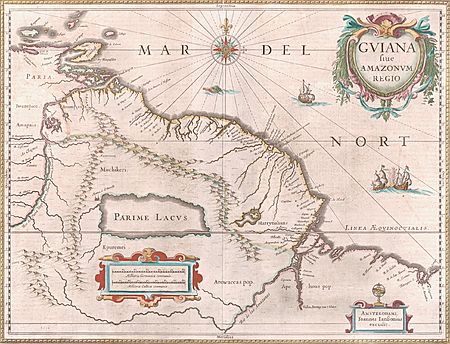

One important thing we got from these native peoples is the word "Guiana." This word is often used to describe the area that includes modern Guyana, Suriname (which used to be Dutch Guiana), and French Guiana. The word "Guiana" means "land of waters." This name fits well because the area has many rivers and streams.

Historians believe that the Arawaks and Caribs first lived in the South American hinterland (the remote inland areas). They then moved north, first to the Guianas and then to the Caribbean islands. The Arawak people were mostly farmers, hunters, and fishermen. They moved to the Caribbean islands before the Carib people and settled across the region.

The peaceful Arawak society changed when the warlike Carib people arrived from inland South America. The Carib were known for fighting, and their move north had a big impact. By the late 1400s, the Carib had pushed the Arawak out of the islands of the Lesser Antilles.

The Carib settlement in the Lesser Antilles also affected Guyana's future. When Spanish explorers and settlers came after Columbus, they found the Arawak easier to conquer than the Carib. The Carib fought hard to stay independent. Because of this strong resistance and the lack of gold in the Lesser Antilles, the Spanish focused on conquering and settling the Greater Antilles and the mainland. Spain made only a small effort to control the Lesser Antilles (except for Trinidad) and the Guianas.

Colonial Guyana

Early European Settlements

The Dutch were the first Europeans to settle in what is now Guyana. The Netherlands had gained independence from Spain in the late 1500s. By the early 1600s, they became a major trading power. They traded with the new English and French colonies in the Lesser Antilles.

In 1616, the Dutch set up the first European settlement in Guyana. It was a trading post about twenty-five kilometers up the Essequibo River. Other settlements followed, usually a few kilometers inland along larger rivers. At first, the Dutch settlements were for trading with the native people. But soon, the Dutch wanted to claim land as other European countries started colonies in the Caribbean.

Even though Spain claimed Guyana, the Dutch took control of the region in the early 1600s. Dutch control was officially recognized when the Treaty of Munster was signed in 1648.

In 1621, the Dutch government gave the new Dutch West India Company full control over the trading post on the Essequibo. This Dutch company managed the colony, known as Essequibo, for over 170 years. The company started a second colony, on the Berbice River southeast of Essequibo, in 1627. This settlement, called Berbice, was governed separately. Demerara, located between Essequibo and Berbice, was settled in 1741. It became a separate colony under the Dutch West India Company in 1773.

The Dutch colonizers first came for trade. But their colonies soon became important for growing crops. In 1623, Essequibo exported 15,000 kilograms of tobacco. As farming grew, there was a shortage of workers. The native people were not suited for plantation work, and many died from diseases brought by Europeans.

The Dutch West India Company then started bringing in enslaved Africans. These enslaved people quickly became a key part of the colonial economy. By the 1660s, there were about 2,500 enslaved people. The number of native people was estimated at 50,000, most of whom had moved into the vast inland areas.

Enslaved Africans were vital to the economy, but their working conditions were very harsh. Many died, and the terrible conditions led to more than half a dozen rebellions by enslaved Africans.

The most famous uprising of enslaved Africans was the Berbice Slave Uprising, which began in February 1763. Enslaved people on two plantations on the Canje River in Berbice rebelled and took control of the region. As more plantations fell to the enslaved Africans, the European population fled. Eventually, only half of the white people who lived in the colony remained.

Led by Coffy (now a national hero of Guyana), the escaped enslaved Africans grew to about 3,000. They threatened European control over the Guianas. The rebels were defeated with help from troops from nearby European colonies like the British, French, Sint Eustatius, and from the Dutch Republic. The 1763 Monument in Georgetown, Guyana, remembers this uprising.

Becoming a British Colony

The Dutch wanted more settlers, so in 1746, they opened the area near the Demerara River to British immigrants. British plantation owners in the Lesser Antilles had problems with poor soil. Many were drawn to the Dutch colonies by richer soils and the chance to own land. So many British citizens came that by 1760, the English were the majority of the European population in Demerara. By 1786, British people effectively controlled the internal affairs of this Dutch colony.

As the economies of Demerara and Essequibo grew, problems appeared between the plantation owners and the Dutch West India Company. Changes in how the government was run in the early 1770s greatly increased costs. The company often tried to raise taxes to cover these costs, which made the plantation owners angry.

In 1781, a war broke out between the Netherlands and Britain. This led to the British taking over Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara. A few months later, France, who was allied with the Netherlands, took control of the colonies. The French ruled for two years. During this time, they built a new town, Longchamps, at the mouth of the Demerara River. When the Dutch regained power in 1784, they moved their colonial capital to Longchamps. They renamed it Stabroek. In 1812, the British renamed the capital Georgetown.

When the Dutch returned to power, conflicts between the plantation owners of Essequibo and Demerara and the Dutch West India Company started again. The colonists were worried about plans to increase the slave tax and reduce their say in the colony's government. They asked the Dutch government to listen to their complaints. In response, a special committee was formed. This committee wrote a report called the Concept Plan of Redress. This document suggested big changes to the government. It later became the basis for the British government structure.

The plan suggested a decision-making body called the Court of Policy. There would also be two courts of justice, one for Demerara and one for Essequibo. The members of these courts would include company officials and plantation owners who owned more than twenty-five enslaved people. The Dutch group sent to set up this new system reported very bad things about the Dutch West India Company's management. So, the company's charter was allowed to end in 1792. The Concept Plan of Redress was then put into action in Demerara and Essequibo. The area was renamed the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo. It then came under the direct control of the Dutch government. Berbice remained a separate colony.

The main reason for Britain to formally take over was the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars that followed. In 1795, the French took over the Netherlands. The British declared war on France. In 1796, they sent troops from Barbados to take over the Dutch colonies. The British takeover was peaceful. The local Dutch government in the colony was mostly left alone under the rules of the Concept Plan of Redress.

Both Berbice and the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo were under British control from 1796 to 1802. Through the Treaty of Amiens, both were given back to Dutch control. However, peace did not last long. The war between Britain and France started again in less than a year. In 1803, British troops seized the United Colony and Berbice once more. At the London Convention of 1814, both colonies were officially given to Britain. In 1831, Berbice and the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo were joined together as British Guiana. The colony remained under British control until it became independent in 1966.

Border Dispute with Venezuela

When Britain officially took control of what is now Guyana in 1814, it also became involved in a long-lasting border dispute. At the London Convention of 1814, the Dutch gave the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo and Berbice to the British. This colony had the Essequibo River as its western border with the Spanish colony of Venezuela. Even though Spain still claimed the region, they did not argue against the treaty. This was because they were busy with their own colonies fighting for independence.

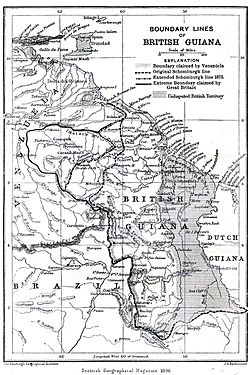

In 1835, the British government asked a German explorer named Robert Hermann Schomburgk to map British Guiana and mark its borders. As the British told him, Schomburgk started British Guiana's western border with Venezuela at the mouth of the Orinoco River. However, all Venezuelan maps showed the Essequibo River as the eastern border of their country. A map of the British colony was published in 1840. Venezuela protested, claiming the entire area west of the Essequibo River. Talks between Britain and Venezuela about the border began, but they could not agree. In 1850, both agreed not to occupy the disputed area.

The discovery of gold in the disputed area in the late 1850s restarted the argument. British settlers moved into the region, and the British Guiana Mining Company was formed to mine the gold. Over the years, Venezuela protested many times and suggested that an independent group decide the border. But the British government was not interested. Venezuela finally broke off diplomatic relations with Britain in 1887 and asked the United States for help.

At first, the British refused the United States government's suggestion for arbitration. But when President Grover Cleveland threatened to get involved based on the Monroe Doctrine, Britain agreed to let an international group decide the border in 1897.

For two years, the group, made up of two Britons, two Americans, and a Russian, studied the case in Paris, France. Their decision, given in 1899, gave 94 percent of the disputed land to British Guiana. Venezuela only received the mouths of the Orinoco River and a short part of the Atlantic coastline just to the east. Even though Venezuela was unhappy with the decision, a group surveyed a new border based on the award. Both sides accepted the border in 1905. The issue was considered settled for the next fifty years.

Early British Colony and Labor Issues

In the 1800s, a group of European plantation owners controlled political, economic, and social life. Even though they were the smallest group in number, these owners had connections to British businesses in London. They often had close ties to the governor, who was chosen by the British monarch. The plantation owners also controlled exports and the working conditions for most of the people.

The next social group was a small number of freed slaves. Many of these had mixed African and European backgrounds. There were also some Portuguese merchants. At the lowest level of society were most people: the African slaves who lived and worked in the countryside on the plantations. Small groups of Amerindians lived in the inland areas, not connected to colonial life.

Life in the colony changed greatly when slavery ended. Even though the international slave trade was banned in the British Empire in 1807, slavery itself continued. In what is known as the Demerara rebellion of 1823, between 10,000 and 13,000 enslaved people in Demerara-Essequibo rose up against their oppressors. Although the rebellion was easily stopped, the push for ending slavery continued. By 1838, all enslaved people were freed.

The end of slavery had several effects. Most importantly, many former slaves quickly left the plantations. Some moved to towns and villages, feeling that farm work was beneath them. Others combined their money to buy the abandoned estates of their former masters and created their own village communities. Setting up small settlements gave the new Afro-Guyanese communities a chance to grow and sell food. This was an extension of a practice where enslaved people were allowed to keep money from selling extra produce. However, the rise of independent Afro-Guyanese farmers threatened the plantation owners' political power. This was because the owners no longer had almost complete control over the colony's economy.

Ending slavery also brought new ethnic and cultural groups to British Guiana. The departure of Afro-Guyanese from the sugar plantations soon led to a shortage of workers. After failed attempts in the 1800s to attract Portuguese workers from Madeira, the estate owners still did not have enough labor. Portuguese Guyanese did not like plantation work and soon moved into other parts of the economy, especially retail business. There, they competed with the new Afro-Guyanese middle class. About 14,000 Chinese people came to the colony between 1853 and 1912. Like the Portuguese before them, the Chinese Guyanese left the plantations for retail jobs and soon became part of Guyanese society.

Worried about the shrinking number of workers on plantations and a possible decline in the sugar industry, British authorities, like those in Dutch Guiana, began to hire poorly paid indentured workers from India. These East Indians, as they were known locally, signed contracts to work for a certain number of years. In theory, they would then return to India with their savings from working in the sugar fields. Bringing in indentured East Indian workers helped with the labor shortage and added another group to Guyana's mix of people. Most of the Indo-Guyanese workers came from eastern Uttar Pradesh, with a smaller number from Tamil and Telugu-speaking areas in southern India. A small number also came from other areas like Bengal, Punjab, and Gujarat.

Political and Social Changes

British Guiana in the 1800s

The government of the British colony favored white and South Asian plantation owners. The political power of these owners came from the Court of Policy and the two courts of justice. These were set up in the late 1700s under Dutch rule. The Court of Policy made laws and managed the government. It included the governor, three colonial officials, and four colonists, with the governor in charge. The courts of justice handled legal matters, such as giving out licenses and appointing civil servants.

The Court of Policy and the courts of justice, controlled by the plantation owners, were the main centers of power in British Guiana. The colonists who served on these courts were chosen by the governor from a list of names. These names were suggested by two electoral colleges. In turn, the seven members of each College of Electors were elected for life by plantation owners who had twenty-five or more enslaved people. Even though their power was limited to suggesting colonists for the three main government councils, these electoral colleges were a place for plantation owners to push for their political goals.

Raising and spending money was the job of the Combined Court. This court included members of the Court of Policy and six extra financial representatives chosen by the College of Electors. In 1855, the Combined Court also became responsible for setting the salaries of all government officials. This duty made the Combined Court a place of arguments, leading to regular clashes between the governor and the plantation owners.

Other Guyanese people started to demand a government that better represented them in the 1800s. By the late 1880s, the new Afro-Guyanese middle class was pushing for changes to the government. In particular, they wanted to change the Court of Policy into an assembly with ten elected members. They also wanted to make it easier for people to vote and to get rid of the College of Electors. The plantation owners, led by Henry K. Davson, who owned a large plantation, resisted these changes. In London, the plantation owners had allies in the West India Committee and the West India Association of Glasgow. Both of these groups were led by owners with big interests in British Guiana.

Changes to the government in 1891 included some of the things the reformers wanted. The plantation owners lost political influence when the College of Electors was abolished and voting rules were made easier. At the same time, the Court of Policy was made larger, with sixteen members. Eight of these were elected members, whose power would be balanced by eight appointed members. The Combined Court also continued, made up of the Court of Policy and six financial representatives who were now elected. To make sure elected officials did not gain too much power, the governor remained the head of the Court of Policy. The daily duties of the Court of Policy were moved to a new Executive Council, which the governor and plantation owners controlled. The 1891 changes were a big disappointment to the colony's reformers. After the 1892 elections, the members of the new Combined Court were almost the same as before.

Over the next thirty years, there were more, but smaller, political changes. In 1897, the secret ballot was introduced. A reform in 1909 expanded the limited number of voters in British Guiana. For the first time, Afro-Guyanese people made up most of the eligible voters.

Political changes came with social changes. Different ethnic groups competed for more power. The British and Dutch plantation owners did not accept the Portuguese as equals. They tried to keep them as foreigners with no rights in the colony, especially no voting rights. These political tensions led the Portuguese to create the Reform Association. After the anti-Portuguese riots of 1898, the Portuguese realized they needed to work with other groups in Guyanese society who also lacked rights, especially the Afro-Guyanese. Around the start of the 1900s, groups like the Reform Association and the Reform Club began to demand more involvement in the colony's affairs. These groups were mostly made up of a small but vocal new middle class. Even though the new middle class felt for the working class, these political groups did not truly represent a national political or social movement. In fact, workers' complaints usually came out as riots.

Political and Social Changes in the Early 1900s

The Ruimveldt Riots in 1905 shook British Guiana. The seriousness of these outbreaks showed how unhappy workers were with their living conditions. The uprising began in late November 1905 when Georgetown stevedores (dockworkers) went on strike, demanding higher wages. The strike became violent, and other workers joined in sympathy. This created the country's first alliance between urban and rural workers. On November 30, crowds of people filled the streets of Georgetown. By December 1, 1905, known as Black Friday, the situation was out of control. At Plantation Ruimveldt, near Georgetown, a large crowd of porters refused to leave when ordered by police and soldiers. The colonial authorities opened fire, and four workers were seriously injured.

News of the shootings spread quickly through Georgetown. Angry crowds started moving through the city, taking over several buildings. By the end of the day, seven people were dead and seventeen badly injured. In a panic, the British government asked for help. Britain sent troops, who finally stopped the uprising. Even though the stevedores' strike failed, the riots planted the seeds for what would become an organized trade union movement.

Even though World War I was fought far from British Guiana, the war changed Guyanese society. Afro-Guyanese people who joined the British military became the core of an important Afro-Guyanese community when they returned. World War I also led to the end of indentured service for East Indians.

In the last years of World War I, the colony's first trade union was formed. The British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) was created in 1917 under the leadership of H.N. Critchlow and led by Alfred A. Thorne. Formed despite strong opposition from businesses, the BGLU at first mostly represented Afro-Guyanese dockworkers. Its membership reached about 13,000 by 1920. It was given legal status in 1921 under the Trades Union Ordinance. Although other unions would not be recognized until 1939, the BGLU showed that the working class was becoming more politically aware and concerned about their rights.

The second trade union, the British Guiana Workers' League, was started in 1931 by Alfred A. Thorne. He led the League for 22 years. The League aimed to improve working conditions for people of all ethnic backgrounds in the colony. Most workers were of West African, East Indian, Chinese, and Portuguese descent. They had been brought to the country under systems of forced or indentured labor.

After World War I, new economic groups started to clash with the Combined Court. The country's economy had become less dependent on sugar and more on rice and bauxite. Producers of these new goods were unhappy that sugar planters still controlled the Combined Court. Meanwhile, the planters were feeling the effects of lower sugar prices. They wanted the Combined Court to provide money for new drainage and irrigation projects.

To stop the arguments and the resulting halt in lawmaking, the Colonial Office announced a new government system in 1928. This system would make British Guiana a crown colony under the strict control of a governor chosen by the Colonial Office. The Combined Court and the Court of Policy were replaced by a Legislative Council with mostly appointed members. For middle-class and working-class political activists, this new system was a step backward and a win for the planters. Influencing the governor, rather than promoting specific public policies, became the most important goal in any political campaign.

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought economic hardship to everyone in Guyanese society. All of the colony's main exports—sugar, rice, and bauxite—were affected by low prices, and unemployment rose sharply. As in the past, the working class found itself without a political voice during a time of worsening economic conditions. By the mid-1930s, British Guiana and the entire British Caribbean experienced labor unrest and violent protests. After riots across the British West Indies, a royal commission led by Lord Moyne was set up to find out why the riots happened and to suggest solutions.

In British Guiana, the Moyne Commission questioned many different people. These included trade unionists, Afro-Guyanese professionals, and representatives of the Indo-Guyanese community. The commission pointed out the deep division between the country's two largest ethnic groups: the Afro-Guyanese and the Indo-Guyanese. The largest group, the Indo-Guyanese, were mainly rural rice farmers or merchants. They had kept the country's traditional culture and did not take part in national politics. The Afro-Guyanese were mostly urban workers or bauxite miners. They had adopted European culture and controlled national politics. To increase the representation of most of the population in British Guiana, the Moyne Commission called for more democratic government and economic and social reforms.

The Moyne Commission report in 1939 was a turning point for British Guiana. It urged giving voting rights to women and people who did not own land. It also encouraged the growing trade union movement. However, none of the Moyne Commission's suggestions were put into action right away because World War II started.

With the fighting far away, the period of World War II in British Guiana saw continued political reform and improvements to the country's infrastructure. The governor, Sir Gordon Lethem, created the country's first Ten-Year Development Plan. He also lowered the property requirements for holding office and voting. In 1943, he made elected members the majority on the Legislative Council. Under the Lend-Lease Act of 1941, a modern air base (now Timehri Airport) was built by United States troops. By the end of World War II, British Guiana's political system had expanded to include more parts of society. The economy's foundations had also been strengthened by increased demand for bauxite.

Road to Independence

Growth of Political Parties

After World War II, people from all parts of society became more politically aware and demanded independence. The years right after the war saw the creation of Guyana's main political parties. The People's Progressive Party (PPP) was founded on January 1, 1950. Later, conflicts within the PPP led to the creation of the People's National Congress (PNC) in 1957. These years also marked the beginning of a long and bitter rivalry between the country's two most important political figures—Cheddi Jagan and Linden Forbes Burnham.

Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Jagan was born in Guyana in 1918. His parents were immigrants from India. His father was a driver, which was considered a lower-middle-class job in Guyanese society. Jagan's childhood gave him a lasting understanding of poverty in rural areas. Despite their poor background, Jagan's father sent his son to Queen's College in Georgetown. After studying there, Jagan went to the United States to study dentistry. He graduated from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois in 1942.

Jagan returned to British Guiana in October 1943. Soon after, his American wife, Janet Rosenberg, joined him. She would play a big role in her new country's political growth. Although Jagan opened his own dentistry clinic, he quickly became involved in politics. After several attempts to get involved in Guyana's political life, Jagan became treasurer of the Manpower Citizens' Association (MPCA) in 1945. The MPCA represented the colony's sugar workers, many of whom were Indo-Guyanese. Jagan's time there was short, as he often disagreed with the more moderate union leaders about policies. Even though he left the MPCA a year after joining, the position allowed Jagan to meet other union leaders in British Guiana and across the English-speaking Caribbean.

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham

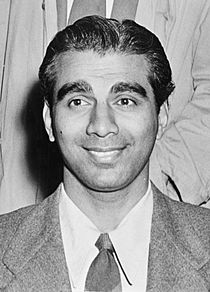

Born in 1923, Forbes Burnham was the only son in a family with three children. His father was the headmaster of Kitty Methodist Primary School, located just outside Georgetown. As part of the colony's educated class, young Burnham was exposed to political ideas early in life. He did very well in school and went to London to get a law degree. Although he did not experience childhood poverty like Jagan, Burnham was very aware of racial discrimination.

The social groups within the urban Afro-Guyanese community in the 1930s and 1940s included a mixed-race or "colored" elite, a black professional middle class, and, at the bottom, the black working class. Unemployment in the 1930s was high. When war broke out in 1939, many Afro-Guyanese joined the military. They hoped to gain new job skills and escape poverty. However, when they returned home from the war, jobs were still hard to find, and discrimination was still a part of life.

Starting the PAC and PPP

The start of Jagan's political career was the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), formed in 1946 as a discussion group. This new group published the PAC Bulletin to share its Marxist ideas and thoughts on freedom and ending colonial rule. The PAC's strong criticism of the colony's poor living standards attracted both supporters and critics.

In the November 1947 general elections, the PAC put forward several members as independent candidates. The PAC's main competitor was the new British Guiana Labour Party. This party, led by J.B. Singh, won six of the fourteen seats. Jagan won a seat and briefly joined the Labour Party. But he had trouble with his new party's moderate ideas and soon left. The Labour Party supported the British governor's policies and could not build support among ordinary people. This slowly made them lose liberal supporters across the country.

The Labour Party's lack of clear plans for reform left a gap, which Jagan quickly filled. Problems on the colony's sugar plantations gave him a chance to become well-known nationally. After the police shootings of five Indo-Guyanese workers on June 16, 1948, at Enmore, near Georgetown, the PAC and the Guiana Industrial Workers' Union (GIWU) organized a large and peaceful protest. This clearly improved Jagan's standing with the Indo-Guyanese population.

After the PAC, Jagan's next big step was founding the People's Progressive Party (PPP) in January 1950. Using the PAC as a base, Jagan created a new party that gained support from both the Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese communities. To get more support among the Afro-Guyanese, Forbes Burnham was brought into the party.

The PPP's first leaders were from different ethnic groups and were left-leaning, but not revolutionary. Jagan became the leader of the PPP's group in parliament, and Burnham took on the role of party chairman. Other key party members included Janet Jagan, Brindley Benn, and Ashton Chase, both PAC veterans. The new party's first win came in the 1950 local elections, where Janet Jagan won a seat. Cheddi Jagan and Burnham did not win seats, but Burnham's campaign made a good impression on many Afro-Guyanese citizens.

From its first victory in the 1950 local election, the PPP gained strength. However, the party's strong anticapitalist and socialist message made the British government uneasy. Colonial officials showed their disapproval of the PPP in 1952. During a regional tour, the Jagans were banned from entering Trinidad and Grenada.

A British commission in 1950 suggested that all adults should be allowed to vote and that British Guiana should adopt a ministerial system of government. The commission also recommended that power should be concentrated in the executive branch, meaning the governor's office. These reforms gave British Guiana's parties a chance to take part in national elections and form a government. However, power remained in the hands of the British-appointed chief executive. This arrangement bothered the PPP, which saw it as an attempt to limit the party's political power.

The First PPP Government

Once the new government system was adopted, elections were set for 1953. The PPP's mix of lower-class Afro-Guyanese and rural Indo-Guyanese workers, along with parts of both ethnic groups' middle classes, formed a strong voting group. Conservatives called the PPP "communist," but the party campaigned on a moderate left platform and appealed to a growing sense of national pride.

The other main party in the election, the National Democratic Party (NDP), was a group that split off from the League of Coloured Peoples. It was mostly an Afro-Guyanese middle-class organization, with some middle-class Portuguese and Indo-Guyanese members. The NDP, along with the poorly organized United Farmers and Workers Party and the United National Party, was soundly defeated by the PPP. The final results gave the PPP eighteen of twenty-four seats, compared to the NDP's two seats and four seats for independent candidates.

The PPP's first government was short-lived. The legislature opened on May 30, 1953. Conservative business groups were already suspicious of Jagan and the PPP's radical ideas. They became even more worried by the new government's plan to expand the government's role in the economy and society. The PPP also tried to put its reform program into action very quickly. This led to conflicts with the governor and high-ranking civil servants who preferred slower change. The issue of civil service appointments also caused problems for the PPP, this time from within. After the 1953 victory, these appointments became a point of disagreement between Jagan's mostly Indo-Guyanese supporters and Burnham's largely Afro-Guyanese supporters. Burnham threatened to split the party if he was not made the sole leader of the PPP. A compromise was reached where members of what had become Burnham's group received government appointments.

The PPP's introduction of the Labour Relations Act caused a conflict with the British. This law was supposedly meant to reduce rivalries between unions. However, it would have favored the GIWU, which was closely linked to the ruling party. The opposition argued that the PPP was trying to control the colony's economic and social life and silence opposition. The day the act was introduced to the legislature, the GIWU went on strike to support the proposed law. The British government saw this mixing of party politics and labor unionism as a direct challenge to the government and the governor's authority. The day after the act was passed, on October 9, 1953, London suspended the colony's constitution. Under the excuse of stopping disturbances, they sent in troops.

The Interim Government

After the constitution was suspended, British Guiana was governed by a temporary administration. This group consisted of a small number of conservative politicians, businessmen, and civil servants. This interim government lasted until 1957. While there was order in the colonial government, a growing split was happening within the country's main political party. The personal conflict between the PPP's Jagan and Burnham grew into a bitter dispute. In 1955, Jagan and Burnham formed rival parts of the PPP. Support for each leader was mostly, but not completely, along ethnic lines. J. P. Lachmansingh, a leading Indo-Guyanese and head of the GIWU, supported Burnham. Jagan kept the loyalty of several important Afro-Guyanese radicals, such as Sydney King. Burnham's part of the PPP moved to the right, leaving Jagan's part on the left. Western governments and the colony's conservative business groups viewed Jagan with considerable concern.

The Second PPP Government

The 1957 elections, held under a new constitution, showed how much ethnic division had grown among Guyanese voters. The updated constitution allowed for limited self-government, mainly through the Legislative Council. Of the council's twenty-four members, fifteen were elected, six were nominated, and the remaining three were to be ex officio members from the interim government. The two parts of the PPP ran strong campaigns, each trying to prove it was the true heir to the original party. Despite denying such intentions, both groups strongly appealed to their own ethnic supporters.

The 1957 elections were clearly won by Jagan's PPP group. Although his group had a strong majority in parliament, its support came more and more from the Indo-Guyanese community. The group's main goals were increasingly seen as Indo-Guyanese: more land for rice, better union representation in the sugar industry, and more business opportunities and government jobs for Indo-Guyanese people.

Jagan's decision to stop British Guiana from joining the West Indies Federation caused him to completely lose Afro-Guyanese support. In the late 1950s, the British Caribbean colonies were actively discussing forming a West Indies Federation. The PPP had promised to work for British Guiana to eventually join a political union with the Caribbean territories. However, the Indo-Guyanese, who were the majority in Guyana, were worried about becoming part of a federation where people of African descent would outnumber them. Jagan's veto of the federation caused his party to lose all significant Afro-Guyanese support.

Burnham learned an important lesson from the 1957 elections. He could not win if he was only supported by the lower-class, urban Afro-Guyanese. He needed middle-class allies, especially those Afro-Guyanese who supported the moderate United Democratic Party. From 1957 onward, Burnham worked to balance keeping the support of the more radical Afro-Guyanese lower classes and gaining the support of the more capitalist middle class. Clearly, Burnham's stated preference for socialism would not unite these two groups against Jagan, who openly supported Marxist ideas. The answer was something simpler: race. Burnham's appeals to race were very successful in bridging the gap that divided the Afro-Guyanese along class lines. This strategy convinced the powerful Afro-Guyanese middle class to accept a leader who was more radical than they would have preferred. At the same time, it lessened the objections of the black working class to joining an alliance with those representing the more moderate interests of the middle classes. Burnham's shift to the right was achieved when his PPP group merged with the United Democratic Party to form a new organization, the People's National Congress (PNC).

After the 1957 elections, Jagan quickly strengthened his hold on the Indo-Guyanese community. Although he openly admired Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and later, Fidel Castro Ruz, Jagan, once in power, stated that the PPP's Marxist-Leninist principles must be adjusted to Guyana's unique situation. Jagan supported the nationalization of foreign-owned businesses, especially in the sugar industry. However, British fears of a communist takeover caused the British governor to limit Jagan's more radical policy plans.

PPP Re-election and Problems

The 1961 elections were a tough competition between the PPP, the PNC, and the United Force (UF). The UF was a conservative party representing big businesses, the Roman Catholic Church, and Amerindian, Chinese, and Portuguese voters. These elections were held under another new government system. This system brought back the level of self-government that briefly existed in 1953. It introduced a bicameral system, meaning two legislative chambers. One was a fully elected thirty-five-member Legislative Assembly, and the other was a thirteen-member Senate appointed by the governor. The position of prime minister was created and was to be filled by the party with the most seats in the Legislative Assembly. With strong support from the Indo-Guyanese population, the PPP won again by a large margin. They gained twenty seats in the Legislative Assembly, compared to eleven seats for the PNC and four for the UF. Jagan was named prime minister.

Jagan's government became increasingly friendly with communist and leftist countries. For example, Jagan refused to follow the United States' ban on trade with communist Cuba. After talks between Jagan and Cuban revolutionary Ernesto "Che" Guevara in 1960 and 1961, Cuba offered British Guiana loans and equipment. In addition, the Jagan government signed trade agreements with Hungary and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

From 1961 to 1964, Jagan faced a campaign to destabilize his government, carried out by the PNC and UF. Besides Jagan's local opponents, the American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD) played an important role. This organization was said to be a front for the CIA. Various reports claim that AIFLD, with a budget of US$800,000, paid anti-Jagan labor leaders. It also had an AIFLD-trained staff of 11 activists who were assigned to organize riots and destabilize Jagan's government. Riots and protests against the PPP government were frequent. During disturbances in 1962 and 1963, angry crowds destroyed parts of Georgetown, causing $40 million in damage.

To counter the MPCA, which was linked to Burnham, the PPP formed the Guiana Agricultural Workers Union. This new union's goal was to organize the Indo-Guyanese sugarcane field-workers. The MPCA immediately responded with a one-day strike to show its continued control over the sugar workers.

The PPP government responded to the strike in March 1964 by publishing a new Labour Relations Bill. This bill was almost the same as the 1953 law that had led to British intervention. Seen as a power play to control a key labor sector, the introduction of the proposed law caused protests and rallies throughout the capital. Riots broke out on April 5. These were followed on April 18 by a general strike. By May 9, the governor had to declare a state of emergency. Nevertheless, the strike continued until July 7, when the Labour Relations Bill was allowed to expire without becoming law. To end the disorder, the government agreed to talk with union representatives before introducing similar bills. These disturbances made the tension and dislike between the two major ethnic communities worse. They made it impossible for Jagan and Burnham to reconcile.

Jagan's term had not yet ended when another wave of labor unrest hit the colony. The pro-PPP GIWU, which had become a large group of all labor organizations, called on sugar workers to strike in January 1964. To make their point, Jagan led a march of sugar workers from the interior to Georgetown. This demonstration sparked outbreaks of violence that quickly grew beyond the authorities' control. On May 22, the governor finally declared another state of emergency. The situation continued to worsen, and in June, the governor took full control. He quickly brought in British troops to restore order and announced a temporary ban on all political activity. By the end of the chaos, 160 people were dead, and over 1,000 homes had been destroyed.

To try and stop the chaos, the country's political parties asked the British government to change the constitution. They wanted a system with more proportional representation. The colonial secretary suggested a fifty-three-member single-chamber legislature. Despite opposition from the ruling PPP, all reforms were put into place, and new elections were set for October 1964.

As Jagan feared, the PPP lost the general elections of 1964. The politics of apan jhaat, a Hindi phrase meaning "vote for your own kind," became deeply rooted in Guyana. The PPP won 46 percent of the vote and twenty-four seats. This made it the largest single party, but it did not have an overall majority. However, the PNC, which won 40 percent of the vote and twenty-two seats, and the UF, which won 11 percent of the vote and seven seats, formed a coalition. The socialist PNC and the openly capitalist UF had joined forces to keep the PPP out of office for another term. Jagan called the election fraudulent and refused to resign as prime minister. The constitution was changed to allow the governor to remove Jagan from office. Burnham became prime minister on December 14, 1964.

Independence and the Burnham Era

Burnham Takes Power

In the first year under Forbes Burnham, conditions in the colony started to become stable. The new coalition government ended diplomatic ties with Cuba. It also put in place policies that favored local investors and foreign businesses. The colony used the renewed flow of Western aid to further develop its infrastructure. A conference to discuss the constitution was held in London. This conference set May 26, 1966, as the date for the colony's independence. By the time independence was achieved, the country was experiencing economic growth and relative peace at home.

The newly independent Guyana first tried to improve relations with its neighbors. For example, in December 1965, the country became a founding member of the Caribbean Free Trade Association (Carifta). However, relations with Venezuela were not peaceful. In 1962, Venezuela announced that it was rejecting the 1899 border agreement. It would renew its claim to all of Guyana west of the Essequibo River. In 1966, Venezuela seized the Guyanese half of Ankoko Island, in the Cuyuni River. Two years later, it claimed a strip of sea along Guyana's western coast.

Another challenge to the new independent government came in early January 1969, with the Rupununi Uprising. In the Rupununi region in southwest Guyana, along the Venezuelan border, white settlers and Amerindians rebelled against the central government. Several Guyanese policemen in the area were killed. Spokesmen for the rebels declared the area independent and asked for Venezuelan help. Troops arrived from Georgetown within days, and the rebellion was quickly put down. Although the rebellion was not a large event, it showed hidden tensions in the new state and the Amerindians' limited role in the country's political and social life.

The Cooperative Republic

The 1968 elections allowed the PNC to rule without the UF. The PNC won thirty seats, the PPP won nineteen seats, and the UF won four seats. However, many observers said the elections were unfair due to manipulation and pressure by the PNC. The PPP and UF were part of Guyana's political scene but were ignored as Burnham began to turn the government into a tool of the PNC.

After the 1968 elections, Burnham's policies became more left-leaning. He announced he would lead Guyana to socialism. He strengthened his control over domestic policies by changing voting districts unfairly (gerrymandering), manipulating the voting process, and making the civil service political. A few Indo-Guyanese were brought into the PNC, but the ruling party clearly represented the Afro-Guyanese political will. Although the Afro-Guyanese middle class was uneasy with Burnham's left-leaning ideas, the PNC remained a shield against Indo-Guyanese dominance. The support of the Afro-Guyanese community allowed the PNC to take control of the economy and start organizing the country into cooperatives.

On February 23, 1970, Guyana declared itself a "cooperative republic." It cut all ties to the British monarchy. The governor general was replaced as head of state by a ceremonial president. Relations with Cuba improved, and Guyana became a strong voice in the Nonaligned Movement. In August 1972, Burnham hosted the Conference of Foreign Ministers of Nonaligned Countries in Georgetown. He used this chance to speak about the problems of imperialism and the need to support African liberation movements in southern Africa. Burnham also allowed Cuban troops to use Guyana as a stopping point on their way to the war in Angola in the mid-1970s.

In the early 1970s, election fraud became very obvious in Guyana. PNC victories always included votes from overseas, who consistently and overwhelmingly voted for the ruling party. The police and military intimidated the Indo-Guyanese. The army was accused of tampering with ballot boxes.

The 1973 elections were seen as a low point for democracy. After these elections, the constitution was changed to stop legal appeals to the Privy Council in London. After gaining power legally and through elections, Burnham focused on getting people to support what he called Guyana's cultural revolution. A program of national service was introduced. It focused on self-reliance, meaning Guyana's people would feed, clothe, and house themselves without outside help.

Government authoritarianism increased in 1974 when Burnham issued the Declaration of Sophia. In it, he stated that "the Party should unapologetically have supreme power over the Government, which is merely one of its executive arms." All parts of the state would be seen as agencies of the ruling PNC and under its control. The state and the PNC became interchangeable; PNC goals were now public policy. The Declaration also called for a move to a socialist state and the nationalization of its economy.

Burnham's control in Guyana was not complete; opposition groups were allowed within limits. For example, in 1973, the Working People's Alliance (WPA) was founded. Opposed to Burnham's authoritarian rule, the WPA was a multi-ethnic group of politicians and thinkers. They supported racial harmony, free elections, and democratic socialism. Although the WPA did not become an official political party until 1979, it grew as an alternative to Burnham's PNC and Jagan's PPP.

Jagan's political career continued to decline in the 1970s. Outmaneuvered in parliament, the PPP leader tried another approach. In April 1975, the PPP ended its boycott of parliament. Jagan stated that the PPP's policy would change from non-cooperation and civil resistance to critical support of the Burnham government. Soon after, Jagan appeared on the same platform with Prime Minister Burnham at the celebration of ten years of Guyanese independence, on May 26, 1976.

Despite Jagan's attempt to be friendly, Burnham had no intention of sharing power. He continued to secure his position. When suggestions for new elections and PPP involvement in the government were ignored, the mostly Indo-Guyanese sugar workers went on a bitter strike. The strike was broken, and sugar production dropped sharply from 1976 to 1977. The PNC postponed the 1978 elections. Instead, they chose to hold a referendum in July 1978, proposing to keep the current assembly in power.

The July 1978 national referendum was not well received. Although the PNC government proudly announced that 71 percent of eligible voters participated and that 97 percent approved the referendum, other estimates put voter turnout at 10 to 14 percent. The low turnout was largely due to a boycott led by the PPP, WPA, and other opposition groups.

Burnham's Last Years

Guyanese politics saw a violent year in 1979. Some of this violence was aimed at the WPA, which had become a strong critic of the state and of Burnham in particular. One of the party's leaders, Walter Rodney, and several professors at the University of Guyana were arrested on arson charges. The professors were soon released, and Rodney was granted bail. WPA leaders then organized the alliance into Guyana's most vocal opposition party.

A new constitution was announced in 1980. The old ceremonial position of president was removed. The head of government became the executive president, chosen, like the former prime minister, by the majority party in the National Assembly. Burnham automatically became Guyana's first executive president and promised elections later that year. In elections held on December 15, 1980, the PNC claimed 77 percent of the vote and forty-one of the fifty-three directly elected seats, plus the ten chosen by the regional councils. The PPP and UF won ten and two seats, respectively. The WPA refused to participate in an election it considered unfair. Opposition claims of election fraud were supported by a team of international observers led by Britain's Lord Avebury.

The economic crisis in Guyana in the early 1980s got much worse. This was accompanied by a rapid decline in public services, infrastructure, and overall quality of life. Power outages happened almost daily, and water services were increasingly poor. Guyana's decline included shortages of rice and sugar (both produced in the country), cooking oil, and kerosene. While the official economy struggled, the black market economy in Guyana thrived.

In the middle of this difficult time, Burnham had surgery for a throat problem. On August 6, 1985, while being cared for by Cuban doctors, Guyana's first and only leader since independence died unexpectedly.

From Hoyte to Today

Despite worries that the country would become politically unstable, the transfer of power went smoothly. Vice President Desmond Hoyte became the new executive president and leader of the PNC. His first tasks were three-fold: to secure his authority within the PNC and national government, to lead the PNC through the December 1985 elections, and to restart the struggling economy.

Hoyte's first two goals were easily achieved. The new leader used disagreements within the PNC to quietly strengthen his power. The December 1985 elections gave the PNC 79 percent of the vote and forty-two of the fifty-three directly elected seats. Eight of the remaining eleven seats went to the PPP, two went to the UF, and one to the WPA. Claiming fraud, the opposition boycotted the December 1986 local elections. With no opponents, the PNC won all ninety-one seats in local government.

Restarting the economy proved harder. As a first step, Hoyte slowly began to support the private sector. He recognized that government control of the economy had failed. Hoyte's government removed all limits on foreign business activity and ownership in 1988.

Although the Hoyte government did not completely abandon the strict rule of the Burnham era, it did make some political reforms. Hoyte ended overseas voting and the rules for widespread proxy and postal voting. Independent newspapers were given more freedom, and political harassment decreased a lot.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter visited Guyana to push for free elections to start again. On October 5, 1992, a new National Assembly and regional councils were elected. This was the first Guyanese election since 1964 to be recognized internationally as free and fair. Cheddi Jagan of the PPP was elected and sworn in as President on October 9, 1992. This reversed the control Afro-Guyanese had traditionally held over Guyanese politics. A new International Monetary Fund Structural Adjustment program was introduced. This led to an increase in the country's economic output (GDP) but also reduced real incomes and hit the middle classes hard.

When President Jagan died of a heart attack in March 1997, Prime Minister Samuel Hinds replaced him, as allowed by the constitution. Jagan's widow, Janet Jagan, became Prime Minister. She was then elected President on December 15, 1997, for the PPP. However, Desmond Hoyte's PNC challenged the results. This led to strikes, riots, and one death before a Caricom mediating committee was brought in. Janet Jagan's PPP government was sworn in on December 24. They agreed to review the constitution and hold elections within three years, though Hoyte refused to recognize her government.

Jagan resigned in August 1999 due to poor health. She was succeeded by Finance Minister Bharrat Jagdeo, who had been named Prime Minister a day earlier. National elections were held on March 19, 2001, three months later than planned because the election committees said they were not ready. In March, incumbent President Jagdeo won the election with a voter turnout of over 90%.

Meanwhile, tensions with Suriname became very strained due to a dispute over their shared maritime border. This happened after Guyana allowed oil-prospectors to explore the areas.

In December 2002, Hoyte died. Robert Corbin replaced him as leader of the PNC. He agreed to engage in 'constructive engagement' with Jagdeo and the PPP.

Severe flooding from heavy rainfall caused great damage in Guyana starting in January 2005. The downpour, which lasted about six weeks, flooded the coastal area. It caused the deaths of 34 people and destroyed large parts of the rice and sugarcane crops. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated in March that the country would need $415 million for recovery and rebuilding. About 275,000 people—37% of the population—were affected in some way by the floods. In 2013, the Hope Canal was completed to help with flooding.

In May 2008, President Bharrat Jagdeo signed The UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations. On February 12, 2010, Guyana officially joined the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR).

In December 2011, President Bharrat Jagdeo was succeeded by Donald Ramotar of the ruling People's Progressive Party (PPP/C). However, the ruling party, mainly supported by Guyana's ethnic-Indians, lost its majority in parliament for the first time in 19 years.

In May 2015, David Granger of A Partnership for National Unity and Alliance for Change (APNU+AFC) narrowly won the elections. He represented the alliance of Afro-Guyanese parties. In May 2015, David Granger was sworn in as the new President of Guyana.

In August 2020, the 75-year-old incumbent David Granger narrowly lost and did not accept the result. Irfaan Ali of the People's Progressive Party/Civic was sworn in as the new president five months after the election. This delay was due to claims of fraud and irregularities.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Guyana para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Guyana para niños

- British colonization of the Americas

- French colonization of the Americas

- History of the Americas

- History of the British West Indies

- History of South America

- History of the Caribbean

- Politics of Guyana

- List of governors of British Guiana

- List of governors-general of Guyana

- List of presidents of Guyana

- List of prime ministers of Guyana

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |