History of Hawaii facts for kids

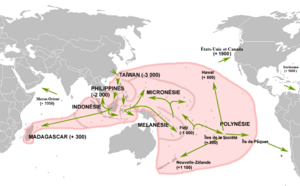

The history of Hawaii tells the story of people living on the Hawaiian Islands. The first people to settle here were Polynesians, arriving sometime between 124 and 1120 AD. For at least 500 years, Hawaiian civilization grew on its own, separate from the rest of the world.

In 1778, James Cook, a British explorer, led the first group of Europeans to arrive in Hawaii. However, some historians believe Spanish captain Ruy López de Villalobos saw the islands earlier in 1542. Just five years after Cook's arrival, European tools and weapons helped Kamehameha I, the ruler of Hawaii Island, conquer and unite all the islands. He created the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1795. This kingdom became important because of its farming and its key location in the Pacific Ocean.

Soon after Cook's visit, Americans, especially Protestant missionaries, started moving to Hawaii. Many Native Hawaiians also left, often on whaling ships. Americans began setting up large farms called plantations to grow sugar. These farms needed many workers. So, many people came from Japan, China, and the Philippines to work in the fields. By 1896, about 25% of Hawaii's population was from Japan. The Hawaiian monarchy welcomed this mix of cultures. In 1840, they set up a government that aimed for equal voting rights for everyone, no matter their race, gender, or wealth.

The number of Native Hawaiians living in Hawaii dropped significantly after 1778. From an estimated 300,000, it fell to about 142,000 by the 1820s. By 1900, after Hawaii joined the United States, the population was around 37,656. However, since Hawaii became part of the U.S., the Native Hawaiian population has grown with each census, reaching 289,970 in 2010.

Later, Americans working in the Hawaiian government changed the constitution. This greatly reduced the power of King Kalākaua and took away voting rights from most Native Hawaiians and Asian citizens. They did this by making property and income requirements very high, which mostly helped plantation owners. In 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani tried to bring back the king's power. But businessmen, with help from the U.S. military, put her under house arrest. Against the Queen's wishes, the Republic of Hawaii was formed for a short time. This government agreed for Hawaii to join the United States in 1898 as the Territory of Hawaii. Finally, in 1959, the islands became the 50th state of Hawaii.

Contents

Ancient Hawaii

First Settlements

The exact date when the Hawaiian Islands were first settled is still debated. Archaeology suggests people might have arrived as early as 124 AD. Some experts like Patrick Vinton Kirch believe the first Polynesian settlements were around 300 AD, or even as late as 600 AD. Other ideas suggest dates between 700 and 800 AD. Newer studies using advanced dating methods suggest settlements might have started after 1120 AD.

The history of the ancient Polynesians was passed down through special chants. These chants told the stories of their family lines and were recited at important events. The highest chiefs, called pua aliʻi, were thought to be like living gods.

By about 1000 AD, people living along the coasts of the islands began to grow food in gardens.

Around 1200 AD, a priest from Tahiti named Pā‘ao is said to have brought new rules to the islands. This new system created different social classes. The aliʻi nui was the king, with his ʻaha kuhina just below him. The aliʻi were the royal nobles, followed by the kahuna (high priest). Next were the makaʻāinana (common people), and the kauā were the lowest class.

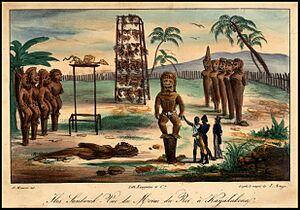

The rulers of Hawaii, called noho aliʻi o ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻAina, were Native Hawaiians who ruled different parts of the islands. Their family history goes back to Hānalaʻanui. The aliʻi nui made sure people followed a strict kapu system. This was a code of conduct with rules about many things, like fishing rights and even where women could eat. After Kamehameha I died, the kapu system was ended, and the Hawaiian religion soon changed as the old gods were no longer worshipped.

By 1500, Hawaiians started moving inland and their religion became even more important.

Hawaiian Religion

Hawaiian religion is similar to other Polynesian cultures, with its own beliefs, ceremonies, and rules. There are many gods and heroes. Wākea, the Sky Father, married Papahānaumoku, the Earth Mother. From them came all other beings, including the other gods.

Hawaiian religion was polytheistic, meaning people worshipped many gods. Four main gods were most important: Kāne, Kū, Lono, and Kanaloa. Other well-known gods include Laka, Kihawahine, Haumea, Papahānaumoku, and the famous volcano goddess, Pele. Also, each family had one or more guardian spirits or family gods called ʻaumakua to protect them. Iolani was one such god, protecting aliʻi families.

The Hawaiian pantheon (group of gods) can be divided into different groups:

- Four major gods (ka hā) – Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa.

- Forty male gods or aspects of Kāne (ke kanahā).

- Four hundred gods and goddesses (ka lau).

- Many other gods and goddesses (ke kini akua).

- Spirits (na ʻunihipili).

- Guardians (na ʻaumākua).

Another way to group them is:

- Four main gods, or akua: Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa.

- Many smaller gods, or kupua, each linked to certain jobs.

- Guardian spirits, ʻaumākua, linked to specific families.

Liloa, Hākau and ʻUmi a Līloa

Liloa's Rule

Līloa was a famous ruler of Hawaii Island in the late 1400s. His royal home was in Waipiʻo Valley. His family line was traced back to the very beginning of Hawaiian history.

Līloa had two sons. His first son, Hākau, was from his wife Pinea. His second son, ʻUmi a Līloa, was from his second wife, Akahi a Kuleana, who was of a lower rank. When Līloa died, he made Hākau the ruler and gave ʻUmi religious authority. Akahi a Kuleana was a chiefess of a lower family line. Līloa fell in love with her when he saw her bathing in a river while visiting Hamakua. He claimed her as his right as King, and she accepted.

Līloa's sacred feathered sash, called Liloa's Kāʻei, is now kept at the Bishop Museum.

Līloa was the first son of Kiha nui lulu moku, one of the ruling elite. He came from the family of Hāna laʻa nui. Līloa's mother, Waioloa, and his grandmothers were from the ʻEwa aliʻi families of Oahu. Līloa's father ruled Hawaii as aliʻi nui and made Līloa the next ruler when he died.

Hākau's Reign

Before he died, Līloa made Hākau the next chief. He told ʻUmi to serve as Hākau's "man" (like a Prime Minister) and that they should respect each other. At first, Hākau was a good king, but he soon became mean. To avoid his brother's anger, ʻUmi went to live in another district.

Hākau refused to help Nunu and Ka-hohe, two of his father's favorite priests, who were sick and asked for food. This was a great insult. These priests served the god Lono. They were angry and planned to put someone else on the throne. Hākau did not believe the priests had any power and disrespected them because ʻUmi was the spiritual leader. At that time, no king could defy a priest. Many priests had royal blood, owned land, and could even be warriors, but they always kept their spiritual duties. The two priests contacted ʻUmi's supporters through a messenger. They then traveled to Waipunalei to support ʻUmi's plan to overthrow Hākau.

When Hākau heard that his brother was preparing for war, he sent his main forces to gather feathers for their war clothes. While his men were away and Hākau was unprotected, ʻUmi's men came forward. They pretended to bring bundles of offerings for the king. But when they dropped the bundles, they were full of rocks, which they used to stone Hākau to death.

ʻUmi-a-Līloa's Rule

ʻUmi-a-Līloa became the ruling chief of Hawaii Island after Hākau's death. He was known as a fair and religious ruler. He was the first to unite almost all of the Big Island. The story of ʻUmi-a-Līloa is one of the most popular hero stories in Hawaiian history.

ʻUmi-a-Līloa's wife was Princess Piʻikea, the daughter of Piʻilani. They had a son named Kumalae and a daughter named Aihākōkō.

Līloa had told Akahi that if she had a son, she should bring the boy to him with special royal gifts he had given her. These gifts would prove the boy was the king's son. Akahi hid the gifts from her husband. Later, she gave birth to a son. When the boy was about 15 or 16, his stepfather was punishing him. His mother stepped in and told the man not to touch him, saying the boy was his lord and chief. She showed the gifts to her husband to prove he was committing a serious offense. Akahi gave her son the royal malo (loincloth) and lei niho palaoa (necklace) that Līloa had given her. Only high chiefs wore these items. She sent ʻUmi to Waipiʻo Valley to present himself to the king as his son.

Līloa's palace was guarded by several Kahuna (priests). The entire area was sacred, and entering without permission meant death. But ʻUmi entered with his attendants, who were afraid to stop someone wearing royal symbols. He walked straight to Līloa's sleeping area and woke him. When Līloa asked who he was, ʻUmi said, "It is I, ʻUmi your son." He then placed the royal gifts at his father's feet, and Līloa declared him his son. Hākau became upset when he learned about ʻUmi. Līloa assured his first son that he would be king after his death and that his brother would serve him. ʻUmi was brought to court and treated as equal to Hākau. Living in Līloa's court, ʻUmi gained much favor from his father, which made Hākau dislike him even more.

While in exile, ʻUmi married and began to gather supporters. Chiefs started to believe he was a true high chief because of signs they saw. He gave food to people and became known for caring for everyone.

After Hākau's death, other chiefs on the island claimed their districts for themselves. ʻUmi followed the advice of the two priests. He married many high-ranking noblewomen, including his half-sister Kapukini and the daughter of the ruler of Hilo, where he had found safety during Hākau's rule. Eventually, ʻUmi conquered the entire island.

After uniting Hawaii Island, ʻUmi was loyal to those who had supported him. He allowed his three most trusted companions and the two priests who helped him to govern with him.

Land Division System

Land was divided strictly according to the wishes of the Ali‘i Nui (high chiefs). The traditional land system had four main levels:

- mokupuni (island)

- moku (smaller parts of an island)

- ahupuaʻa (parts of a moku)

- ʻili (two or three per ahupuaʻa)

Some stories say that ʻUmi a Līloa created the ahupuaʻa system. This system used the fact that communities were already organized along stream systems. The way they managed water, called Kānāwai, is also linked to shared water use.

The Hawaiian farming system had two main types: irrigated (watered) and rain-fed (dryland) systems. Irrigated systems mainly grew taro (kalo). Rain-fed systems were called mala. There, they grew uala (sweet potatoes), yams, and dryland taro. They also grew coconuts (niu), breadfruit (ʻulu), bananas (maiʻa), and sugarcane (ko). The kukui tree (Aleurites moluccanus) was sometimes used to shade the mala from the sun. Each crop was planted in the best place for it to grow.

Hawaiians raised dogs, chickens, and pigs. They also grew small gardens at home. Water was very important for Hawaiian life. It was used for fishing, bathing, drinking, and gardening. They also had aquaculture systems in rivers and along the shore for raising fish.

An ahupuaʻa was usually a section of an island that stretched from the top of a mountain down to the coast. It often followed the path of a stream. Each ahupuaʻa included lowland farms and an upland forest area. The size of ahupuaʻa varied depending on the area's resources and political divisions. Hawaiians believed that the land, sea, clouds, and all of nature were connected. They used all resources around them to achieve a good balance, or pono. This balance was kept by the konohiki (land managers) and kahuna (priests). They would limit fishing for certain species during specific seasons and control plant gathering.

The word "ahupuaʻa" comes from Hawaiian words: ahu meaning "heap" or "cairn," and puaʻa meaning "pig". The boundary markers for ahupuaʻa were traditionally piles of stones. These stones were used to hold offerings for the island chief, often a pig.

Each ahupuaʻa was divided into smaller parts called ʻili, and ʻili were divided into kuleana. These were individual plots of land farmed by commoners. They paid labor taxes to the land overseer each week, which supported the chief. Two reasons for this division are:

- Travel: In many parts of Hawaii, it was easier to travel up and down streams than across different stream valleys.

- Economy: Having all climate and resource zones in each land division meant that each area could provide most of its own needs.

Governance Structure

The Kingdom was managed by an ali'i chief. Smaller areas were controlled by other chiefs and managed by a steward. The leader of a land division or ahupua`a was called a konohiki. Mokus were ruled by an aliʻi ʻaimoku. Ahupua'as were run by a headman or chief called a Konohiki.

Konohiki's Role

A konohiki was like a Land Agent. When a chief appointed someone to manage land, they were called konohiki. The term could also refer to a private land area, different from government land. A chief of lands kept his right to the land for life, even if he was removed from his position. But a headman overseeing the same land did not have this protection.

Often, ali'i (nobles) and konohiki were seen as the same. However, while most konohiki were ali'i nobility, not all ali'i were konohiki. The Hawaiian dictionary defines konohiki as a headman of a land division, and also describes their fishing rights. The word kono means to invite or prompt, and hiki means something that can be done. The konohiki was a relative of the ali'i and looked after the property. They managed water rights, land distribution, agricultural use, and any upkeep. The konohiki also made sure that the right gifts and tributes were given at the correct times.

As capitalism became part of the kingdom, the konohiki became tax collectors, landlords, and fishery wardens.

Contact with Europeans

Captain James Cook led three journeys to map unknown parts of the world for the British Empire. On his third journey, he found Hawaii. He first saw the islands on January 18, 1778. He anchored off the coast of Kauai and met the local people to trade and get water and food. On February 2, 1778, Cook continued to North America and Alaska, looking for a Northwest Passage. About nine months later, he returned to Hawaii to resupply. He explored the coasts of Maui and Hawaii Island, trading with locals. He anchored in Kealakekua Bay in January 1779. After leaving Kealakekua, he returned in February 1779 because a ship's mast broke in bad weather.

On the night of February 13, while anchored in the bay, one of his two longboats (small boats used to go between ship and shore) was stolen by Hawaiians. To get it back, Cook tried to take the aliʻi nui (high chief) of Hawaii Island, Kalaniʻōpuʻu. On February 14, 1779, Cook faced an angry crowd. Kanaʻina approached Cook, who hit the royal attendant with the flat side of his sword. Kanaʻina then picked up Cook and dropped him. Another attendant, Nuaa, killed Cook with a knife.

Kingdom of Hawaii

The Kingdom of Hawaii existed from 1795 until it was overthrown in 1893.

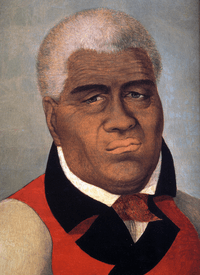

The Kamehameha Family

The House of Kamehameha (Hale O Kamehameha), also known as the Kamehameha dynasty, was the royal family that ruled the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. It began when Kamehameha I founded the kingdom in 1795. It ended with the deaths of Kamehameha V in 1872 and William Charles Lunalilo in 1874.

The Kamehameha family started with two half-brothers, Kalaniʻōpuʻu and Keōua. They shared a mother, Kamakaʻīmoku. Both brothers served Alapaʻinui, the ruling King of Hawaii Island. Some Hawaiian family histories suggest that Keōua might not have been Kamehameha's biological father, and that Kahekili II might have been. However, Kamehameha I's connection to the royal family through his mother, Kekuʻiapoiwa II, is clear. Keōua accepted him as his son, and this is recognized in official family records.

An old chant says that Kamehameha I was born in the winter month of ikuwā, around November. Alapai gave the young Kamehameha to his wife Keaka and her sister Hākau to care for after he found out the boy had lived. Some historians say he was born between 1736 and 1740. He was first named Paiea but later took the name Kamehameha, which means "The very lonely one" or "The one set alone."

Kamehameha's uncle, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, raised him after Keōua's death. Kalaniʻōpuʻu ruled Hawaii, just like his grandfather Keawe. He had advisors and priests. When he heard that chiefs were planning to kill the boy, he told Kamehameha:

"My child, I have heard the secret complaints of the chiefs and their mutterings that they will take you and kill you, perhaps soon. While I am alive they are afraid, but when I die they will take you and kill you. I advise you to go back to Kohala." "I have left you the god; there is your wealth."

After Kalaniʻōpuʻu died, Kīwalaʻō took his father's place as ruler of the island. Kamehameha became the religious leader. Some chiefs supported Kamehameha, and war soon broke out to overthrow Kīwalaʻō. After several battles, the king was killed. Messengers were sent for the last two brothers to meet with Kamehameha. Keōua and Kaōleiokū arrived in separate canoes. Keōua came ashore first, where a fight started, and he and everyone with him were killed. Before the same could happen to the second canoe, Kamehameha stepped in. By 1795, Kamehameha had conquered all but one of the main islands.

For his first royal home, the new King built the first Western-style building in Hawaii, called the "Brick Palace". This place became the center of government for the Hawaiian Kingdom until 1845. The king ordered the building to be built at Keawa'iki point in Lahaina, Maui. Two former prisoners from Australia's Botany Bay built the home. It was started in 1798 and finished four years later in 1802. The house was meant for Kaʻahumanu, but she chose to live in a traditional Hawaiian-style home next to it.

Kamehameha I had many wives, but he respected two the most. Keōpūolani was the highest-ranking chiefess of her time and the mother of his sons, Liholiho and Kauikeaouli. Kaʻahumanu was his favorite. Kamehameha I died in 1819, and Liholiho became king.

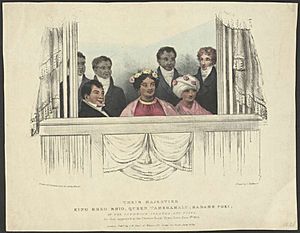

Kamehameha II

After Kamehameha I died, Liholiho left Kailua for a week. When he returned, he was crowned king. At the grand ceremony, attended by commoners and nobles, he approached the chiefs. Kaʻahumanu, the Dowager Queen, told him, "Hear me O Divine one, for I make known to you the will of your father. Behold these chiefs and the men of your father, and these your guns, and this your land, but you and I shall share the realm together." Liholiho officially agreed. This started a unique system of shared rule between a King and a co-ruler, similar to a regent. Kamehameha II shared his rule with his stepmother, Kaʻahumanu. She broke Hawaiian kapu (sacred rules) by eating with the young king, which was forbidden for men and women. This led to the end of the Hawaiian religion. Kamehameha II died, along with his wife, Queen Kamāmalu, in 1824 during a visit to England. They both died from measles. He was King for five years.

The couple's bodies were brought back to Hawaii by Boki. On the ship The Blond, Boki's wife Liliha and Kekūanāoʻa were baptized as Christians. Kaʻahumanu also became Christian and had a strong influence on Hawaiian society until she died in 1832. Since the new king was only 12 years old, Kaʻahumanu was now the senior ruler and named Boki as her Kuhina Nui (co-ruler).

Boki left Hawaii on a trip to find sandalwood to pay off a debt and was lost at sea. His wife, Liliha, became the governor of Maui. She tried to start a rebellion against Kaʻahumanu, but it failed. Kaʻahumanu had already made Kīnaʻu a co-governor after Boki left.

Kaʻahumanu's Influence

Kaʻahumanu was born on Maui around 1777. Her parents were aliʻi of a lower rank. She became Kamehameha's wife when she was fourteen. One visitor, George Vancouver, said she was "one of the finest woman we had yet seen on any of the islands." To marry her, Kamehameha had to agree that her children would be his heirs, even though she had no children of her own.

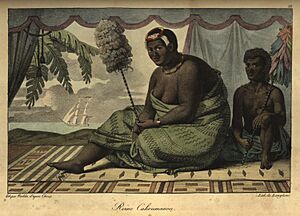

Before he died, Kamehameha chose Kaʻahumanu to rule alongside his son. Kaʻahumanu had also adopted the boy. She had the most political power in the islands. A portrait artist described her: "This Old Dame is the most proud, unbending Lady in the whole island. As the widow of [Kamehameha], she possesses unbound authority and respect, not any of which she is inclined to lay aside on any occasion whatsoever." She was one of Hawaii's most important leaders.

Sugar and Trade Agreements

Sugarcane became a big export from Hawaii soon after Cook arrived. The first permanent plantation started in Kauai in 1835. William Northey Hooper rented land from Kamehameha III and began growing sugarcane. Within 30 years, plantations were operating on the four main islands. Sugar completely changed Hawaii's economy.

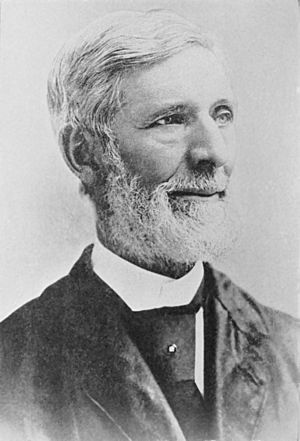

American influence in the Hawaiian government began when U.S. plantation owners demanded a say in the Kingdom's politics. This was driven by missionary beliefs and the sugar business. These plantation owners pressured the King and chiefs for land ownership. After the British took over briefly in 1843, Kamehameha III responded by creating the Great Māhele, which gave land to all Hawaiians, as suggested by missionaries like Gerrit P. Judd.

In the 1850s, the U.S. charged much higher taxes on sugar imported from Hawaii than Hawaiians charged the U.S. So, Kamehameha III wanted a trade agreement. The king wanted to lower U.S. taxes to make Hawaiian sugar competitive with sugar from other countries. In 1854, Kamehameha III suggested a trade agreement between the two countries, but the idea did not pass in the U.S. Senate.

The U.S. thought controlling Hawaii was very important for protecting its west coast. The military was especially interested in Pu'uloa, also known as Pearl Harbor. Charles Reed Bishop, a foreigner who had married into the Kamehameha family, suggested selling one of the harbors. He had become Hawaii's Minister of Foreign Affairs and owned a home near Pu'uloa. He showed two U.S. officers around the area, even though his wife, Bernice Pauahi Bishop, did not approve of selling Hawaiian lands. As king, William Charles Lunalilo was happy to let Bishop handle most business. But giving up land became unpopular with Hawaiians. Many islanders feared that all the islands, not just Pearl Harbor, might be lost. By November 1873, Lunalilo stopped the talks. His health quickly worsened, and he died on February 3, 1874.

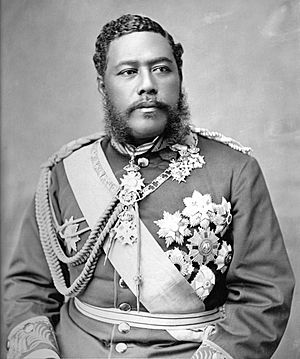

Lunalilo had no children to take his place. The constitution allowed the legislature to choose the next king. They chose David Kalākaua as Lunalilo's successor. The new ruler was pressured by the U.S. government to give Pearl Harbor to the Navy. Kalākaua worried this would lead to the U.S. taking over Hawaii and would go against Hawaiian traditions. Hawaiians believed the land ('Āina) was sacred and not for sale. From 1874 to 1875, Kalākaua visited Washington D.C. to get support for a new treaty. Congress agreed to the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 for seven years, in exchange for Ford Island. After the treaty, sugar production grew greatly. When the seven-year term ended, the United States was not very interested in renewing it.

Rebellion of 1887 and the Bayonet Constitution

On January 20, 1887, the United States began leasing Pearl Harbor. Soon after, a group of mostly non-Hawaiians called the Hawaiian Patriotic League started the Rebellion of 1887. They wrote their own constitution on July 6, 1887.

This new constitution was written by Lorrin A. Thurston, who was Hawaii's Minister of the Interior. He used the Hawaiian military to threaten Kalākaua. Kalākaua was forced to fire his government ministers and sign a new constitution that greatly reduced his power. It became known as the "Bayonet Constitution" because it was forced upon the king.

The Bayonet Constitution allowed the king to appoint government ministers, but he could not fire them without the Legislature's approval. The rules for voting for the House of Nobles changed. Now, both candidates and voters had to own property worth at least $3,000 or have an annual income of $600 or more. This meant two-thirds of Native Hawaiians and other ethnic groups who could vote before, could no longer vote. This constitution helped the foreign plantation owners. With the legislature now in charge of making foreigners citizens, Americans and Europeans could keep their home country citizenship and still vote as citizens of the kingdom. Americans could also hold office and keep their American citizenship, which was not allowed in other countries. Asian immigrants could no longer become citizens or vote.

Wilcox Rebellion of 1888

The Wilcox Rebellion of 1888 was a plan to overthrow King David Kalākaua and replace him with his sister in a takeover. This happened because of growing political tension between the legislature and the king under the 1887 constitution. Kalākaua's sister, Princess Liliʻuokalani, and his wife, Queen Kapiolani, returned from Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in Great Britain as soon as they heard the news.

Kalākaua's distant cousin, Robert William Wilcox, a Native Hawaiian officer and veteran of the Italian military, returned to Hawaii around the same time as Liliʻuokalani in October 1887. This was because funding for his studies stopped. Wilcox, Charles B. Wilson, Princess Liliʻuokalani, and Sam Nowlein planned to overthrow King Kalākaua and replace him with Liliʻuokalani. Three hundred Hawaiian plotters hid in Iolani Barracks. They also formed an alliance with the Royal Guard. But the plot was accidentally discovered in January 1888, less than 48 hours before the revolt. No one was punished, but Wilcox was exiled. On February 11, 1888, Wilcox left Hawaii for San Francisco, planning to return to Italy with his wife.

The Reform Party of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which had forced the Bayonet Constitution on her brother, offered Princess Liliʻuokalani the throne several times. But she believed she would become a powerless figurehead like her brother and refused the offers. In January 1891, Kalākaua traveled to San Francisco for his health and died there on January 20. She then became Queen. Queen Liliʻuokalani called her brother's reign "a golden age materially for Hawaii."

Liliʻuokalani's Attempt to Change the Constitution

Liliʻuokalani became Queen during a time of economic trouble. The McKinley Act had hurt the Hawaiian sugar industry. This law removed taxes on sugar imports from other countries into the U.S., which took away Hawaii's advantage from the 1875 Reciprocity Treaty. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens lost money. In response, Liliʻuokalani suggested a lottery system to raise money for her government. She also controversially proposed allowing opium licensing. Her ministers and closest friends were against these plans. They tried to stop her, but failed. Both ideas were later used against her during the growing constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani's main goal was to bring back power to the monarch by getting rid of the 1887 Bayonet Constitution and creating a new one. This idea seemed to be widely supported by the Hawaiian people. The 1893 Constitution would have given more people the right to vote by lowering some property requirements. It would have also taken away voting rights from many non-citizen Europeans and Americans. The Queen rode horses around several islands, talking to people about her ideas. She received huge support, including a long petition asking for a new constitution. However, when the Queen told her cabinet about her plans, they did not support her. They were worried about how her opponents would react.

Threats to Hawaii's independence appeared throughout the Kingdom's history. But only with the Bayonet Constitution was its independence truly weakened. The event that led to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893, was Liliʻuokalani's attempt to create a new constitution. The plotters wanted to remove the queen, end the monarchy, and have Hawaii join the U.S. The plotters included five Americans, one English person, and one German person.

Overthrow of the Monarchy

The overthrow was led by Thurston, who was the grandson of American missionaries. He got most of his support from American and European businessmen and others who supported the Reform Party of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Most of the leaders of the Committee of Safety who removed the queen were American and European citizens who were subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom. They included lawmakers, government officials, and a Supreme Court Justice of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

On January 16, the Marshal of the Kingdom, Charles B. Wilson, was told by detectives about the planned takeover. Wilson asked for warrants to arrest the 13 Council members and put the Kingdom under martial law (military rule). But because the members had strong political connections with U.S. Government Minister John L. Stevens, the requests were repeatedly denied by Attorney General Arthur P. Peterson and the Queen's cabinet. They feared that if the arrests were approved, it would make the situation worse. After a failed talk with Lorrin A. Thurston, Wilson began to gather his men for the confrontation. Wilson and Captain of the Royal Household Guard Samuel Nowlein gathered 496 men who were ready to protect the Queen.

The overthrow began on January 17, 1893. The Committee of Safety started the takeover by organizing the Honolulu Rifles, a group of about 1,500 armed local (non-native) men. The Rifles took positions at Aliʻiōlani Hale across the street from ʻIolani Palace and waited for the Queen's response.

As these events happened, the Committee of Safety said they were worried about the safety and property of American residents in Honolulu.

United States Military Support

The efforts to overthrow the Queen were supported by U.S. Government Minister John L. Stevens. The takeover left the queen under house arrest at ʻIolani Palace. The Kingdom briefly became the Republic of Hawaii before the United States took it over in 1898. Stevens was told about supposed threats to American lives and property by the Committee of Safety.

So, Stevens called for uniformed U.S. Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of U.S. sailors. They took positions at the U.S. Legation, Consulate, and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. One hundred sixty-two armed sailors and Marines from the USS Boston in Honolulu Harbor came ashore. They were ordered to remain neutral. The sailors and Marines did not enter the Palace grounds or take over any buildings, and they never fired a shot. However, their presence scared the royalist defenders. Historian William Russ states, "the order to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself."

United States Territory

Annexation by the U.S.

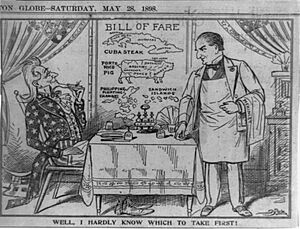

In March 1897, William McKinley, a Republican who wanted the U.S. to expand, became U.S. President after Democrat Grover Cleveland. McKinley prepared a treaty to annex Hawaii, but it did not get the needed two-thirds majority in the Senate because Democrats opposed it. A joint resolution written by Republican Congressman Francis G. Newlands to annex Hawaii passed both the House and Senate. This only needed a simple majority. The Spanish–American War had started, and many leaders wanted control of Pearl Harbor to help the United States become a strong power in the Pacific and protect the West Coast. In 1897, Japan sent warships to Hawaii to oppose annexation. The chance of invasion by Japan made the decision even more urgent.

McKinley signed the Newlands Resolution annexing Hawaii on July 7, 1898, creating the Territory of Hawaii. On February 22, 1900, the Hawaiian Organic Act set up a territorial government. Those against annexation said this was illegal, claiming the Queen was the only rightful ruler. McKinley appointed Sanford B. Dole as territorial governor. The territorial legislature met for the first time on February 20, 1901. Hawaiians formed the Hawaiian Independent Party, led by Robert Wilcox, who became Hawaii's first congressional delegate.

Plantations Grow

Sugarcane plantations in Hawaii grew a lot during the time it was a U.S. territory. Some companies expanded and came to control related businesses like transportation, banking, and real estate. Economic and political power was held by a few large companies, known as the "Big Five".

World War II in Hawaii

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, by the Imperial Japanese Navy. This attack sank the main American battleship fleet. The four Pacific aircraft carriers were not in port and were not damaged. Hawaii was placed under military rule until 1945. The large Japanese American population was not put into camps, but hundreds of pro-Japan leaders were arrested. Pearl Harbor became the U.S.' main base for the Pacific War. The Japanese tried to invade in 1942 but were defeated at the Battle of Midway. Hundreds of thousands of American soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen passed through Hawaii on their way to the fighting.

Many Hawaiians served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. This U.S. Army infantry regiment was made almost entirely of American soldiers of Japanese ancestry. The regiment fought mainly in Italy, southern France, and Germany. The 442nd Regiment was the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in American history. Its 4,000 members had to be replaced almost 2.5 times because of injuries and deaths. In total, about 14,000 men served, earning 9,486 Purple Hearts. The unit received eight Presidential Unit Citations. Twenty-one of its members, including Hawaii U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye, were awarded Medals of Honor. Its motto was "Go for Broke."

Democratic Party Rises

In 1954, there were many non-violent strikes, protests, and other acts of civil disobedience across industries. In the territorial elections of 1954, the Hawaii Republican Party suddenly lost its power in the legislature. It was replaced by the Democratic Party of Hawaii. Democrats pushed for Hawaii to become a state and held the governorship from 1962 to 2002. These events also led to workers forming unions, which sped up the decline of the plantations.

Statehood

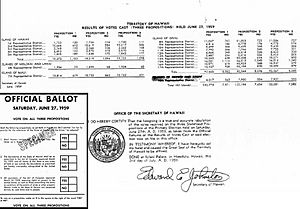

President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the Hawaii Admission Act on March 18, 1959, which allowed Hawaii to become a state. After a public vote where over 93% voted for statehood, Hawaii was admitted as the 50th state on August 21, 1959.

Annexation's Impact

For many Native Hawaiians, the way Hawaii became a U.S. territory was seen as illegal. Hawaii Territory governors and judges were chosen directly by the U.S. President. Native Hawaiians created the Home Rule Party to seek more self-government. Hawaii faced cultural and social pressure during the territorial period and the first ten years of statehood. The Hawaiian Renaissance in the 1960s led to new interest in the Hawaiian language, culture, and identity.

With support from Hawaii Senators Daniel Inouye and Daniel Akaka, Congress passed a joint resolution called the "Apology Resolution" (US Public Law 103-150). President Bill Clinton signed it on November 23, 1993. This resolution apologized "to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893... and the deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination." The meaning of this resolution has been widely discussed.

Akaka proposed what was called the Akaka Bill. This bill aimed to give federal recognition to people of Native Hawaiian ancestry as a self-governing group, similar to Native American tribes. The bill did not pass before his retirement.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Hawái para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Hawái para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |