History of Qatar facts for kids

The history of Qatar tells the story of this land, from when people first lived here to when it became a modern country. Humans have lived in Qatar for about 50,000 years. Old tools and camps from the Stone Age have been found. The first major civilization to have a presence here was Mesopotamia during the Neolithic period, shown by pottery pieces found near the coast.

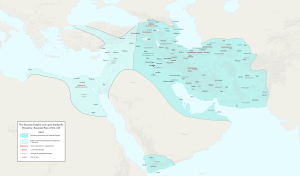

Over many centuries, different empires ruled Qatar, including the Seleucids, Parthians, and Sasanians. In 628 AD, the people learned about Islam after Muhammad sent a messenger to the Sasanid governor. By the 700s, Qatar was a busy place for trading pearls. Many towns grew during the Abbasid era. Later, the Al Khalifa family took control of Bahrain and Qatar in 1783. For a long time, Qatar was a battleground between the Wahhabi from Najd and the Al Khalifa. The Ottomans took over Eastern Arabia in 1871 but left in 1915 because of World War I.

In 1916, Qatar became a British protectorate. This meant that Abdullah Al Thani, the ruler, signed a deal for British protection from sea attacks and support for land attacks. In return, he could only give land to the British. A new treaty in 1934 offered even more protection. In 1935, a company called QatarEnergy got a 75-year deal to search for oil, and high-quality oil was found in Dukhan in 1940.

The 1950s and 1960s were a time of big changes. More oil money meant more wealth, many people moving to Qatar, and great improvements in society. This was the start of modern Qatar. In 1968, Britain said it would end its protection agreements in the Persian Gulf. Qatar planned to join other states to form a federation. But by mid-1971, they still hadn't agreed on how to unite. So, Qatar declared its independence on September 3, 1971. In June 1995, Hamad bin Khalifa became the new ruler in a peaceful change of power from his father, Khalifa bin Hamad. The new ruler allowed more freedom for the press and local elections, leading to a new constitution approved in 2003. It started being used in June 2004.

Contents

Early History of Qatar

Ancient Stone Age Discoveries

In 1961, a Danish team found about 30,000 stone tools from 122 different sites in Qatar. Most of these sites were along the coast. The tools included large scrapers, arrowheads, and hand axes from the early and middle Stone Age.

Around 8,000 years ago, the Persian Gulf flooded. This caused people to move and led to the formation of the Qatari Peninsula. People then started living in Qatar to use its coastal resources. From then on, nomadic tribes from Saudi Arabia often used Qatar as grazing land for their animals. They built seasonal camps near water sources.

Life in the Neolithic Period (8000–3800 BC)

Al Da'asa, on Qatar's western coast, is the largest site from the Ubaid period. The Danish team also explored it in 1961. It's believed to have been a small, seasonal camp for groups who hunted, fished, and gathered food. They found nearly sixty fire pits, possibly used to dry fish, along with flint tools like scrapers and arrowheads. Many painted Ubaid pottery pieces and a carnelian bead were also found, suggesting trade with other places.

In 1977–78, several Ubaid-period graves were found in Al Khor. This is the oldest known burial site in Qatar. One grave held the ashes of a young woman. Eight other graves had items like beads made of shell, carnelian, and obsidian. The obsidian likely came from Najran in southwest Arabia.

Bronze Age Trade and Settlements (2100–1155 BC)

The Dilmun civilization in Bahrain had a strong influence on the Qatari Peninsula. Pottery from Dilmun was found at two sites in Qatar, showing that Qatar was part of Dilmun's trade network. Around 2100 to 1700 BC, people in Qatar started diving for pearls in the Persian Gulf. They also traded pearls and date palms.

Some believe that the Dilmun settlements in Qatar were not for long-term living. Qatar was mostly empty during this time, as nomadic Arab tribes moved around looking for food and water. Settlements from the Dilmun period, especially on Al Khor Island, might have been stops for trade trips between Bahrain and other important places. They could also have been camps for visiting fishermen or pearl divers from Dilmun.

Materials from the Kassite people of Babylonia, dating back to the second millennium BC, were found on Al Khor Island. This shows trade links between Qatar and the Kassites. They found 3 million crushed snail shells and Kassite pottery pieces. It's thought that Qatar was the first place to produce shellfish dye. A purple dye industry run by the Kassites existed on the island. The dye came from the Murex snail and was called "Tyrian purple".

Ancient Times

Iron Age and Persian Rule (680–325 BC)

Around 680 BC, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon successfully attacked Bazu, which included Dilmun and Qatar. So far, no ancient Iron Age settlements have been found in Qatar. This might be because the climate made Qatar harder to live in during that time.

In the 400s BC, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote the first known description of Qatar's people. He called them 'sea-faring Canaanites'.

Greek Influence (325–250 BC)

Around 325 BC, Alexander the Great sent his admiral, Androsthenes of Thasos, to explore the Persian Gulf. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, Seleucus I Nicator took control of the eastern part of the Greek Empire. He expanded his Seleucid Empire east of Babylon, possibly including parts of Eastern Arabia. Greek-style items have been found in Qatar. Pottery pieces with Seleucid features were found north of Dukhan. Also, a group of 100 burial mounds from this time was found in Ras Abrouq. The large number of graves suggests a significant community of sea travelers lived there.

By about 250 BC, the Seleucids lost most of their lands in the Persian Gulf, and their influence in the area ended.

Persian Control (250 BC–642 AD)

After the Parthian Empire took over from the Seleucids around 250 BC, they controlled the Persian Gulf and Arabian Coast. Since the Parthians relied on trade routes through the Persian Gulf, they set up military posts along the coast. Pottery found in Qatar shows connections to the Parthian Empire.

Ras Abrouq, a coastal town north of Dukhan, had a fishing station used by foreign ships to dry fish around 140 BC. Many stone structures and large amounts of fish bones were found there.

Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer, described the people of the peninsula around the mid-first century AD. He called them the "Catharrei" and said they were nomads always looking for water and food. Around the second century, Ptolemy created the first known map to show the land, calling it "Catura".

In 224 AD, the Sasanian Empire took control of the lands around the Persian Gulf. Qatar was important for Sasanid trade, providing precious pearls and purple dye. Sasanid pottery and glass were found in Mezru'ah, northwest of Doha, and in Umm al-Ma'a.

Under Sasanid rule, many people in Eastern Arabia became Christians. Monasteries were built in Qatar during this time, and more settlements were founded. In the later Christian era, Qatar was known by the Syriac name 'Beth Qatraye' (meaning "region of the Qataris"). This area included Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, and Al-Hasa.

In 628 AD, Muhammad sent a Muslim messenger to Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi, a Persian ruler in Eastern Arabia. He asked Munzir and his people to accept Islam. Munzir agreed, and most Arab tribes in Qatar became Muslims. Some historians believe Munzir ibn Sawa's government was in the Murwab or Umm al-Ma'a area of Qatar. This idea is supported by the discovery of about 100 small stone houses and forts in Murwab from the early Islamic period. After becoming Muslim, the Arabs led the Muslim conquest of Persia, which led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire.

It's likely that some settled people in Qatar didn't become Muslim right away. Isaac of Nineveh, a Christian bishop from the 600s, was born in Beth Qatraye. Other important Christian scholars from this time also came from Beth Qatraye.

Caliphate Rule

Umayyad Period (661–750)

During the Umayyad period, Qatar was known as a place for raising horses and camels. In the 700s, it became an important center for pearl trading because of its good location in the Persian Gulf.

During a time of conflict called the Second Fitna, a famous Khariji leader named Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a led many battles. He was known as a very popular and powerful leader and ruled the Azariqa movement for over 10 years. Born in Al Khuwayr in Qatar, he also made the first Kharijite coins, with the earliest dating to 688 or 689.

The Umayyad Caliphate brought many political and religious changes to western Asia. This led to many revolts against the Umayyads in the late 600s, especially in Qatar and Bahrain. Ibn al-Fuja'a led an uprising for more than twenty years.

By 750, people were very unhappy with the Umayyad Caliphate, especially how non-Arab citizens were treated. The Abbasid Revolution overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate, starting the Abbasid period.

Abbasid Period (750–1253)

Many towns, including Murwab, grew during the Abbasid period. Over 100 stone houses, two mosques, and an Abbasid fort were built in Murwab. Murwab fort is the oldest complete fort in Qatar. It was built on the ruins of an older fort that was destroyed by fire. This town was the first large settlement built away from Qatar's coast. A similar site, with pottery from the Tang dynasty, was found in Al Naman (north of Zubarah), dating to the 800s and 900s.

The pearl industry around the Qatari Peninsula grew a lot during the Abbasid era. Ships from Basra going to India and China would stop at Qatar's port. Chinese porcelain, West African coins, and items from Thailand have been found in Qatar. Old findings from the 800s suggest that Qatar's people used their increased wealth, perhaps from pearl trade, to build better homes and public buildings. However, when the caliphate in Iraq became less wealthy, so did Qatar.

Most of Eastern Arabia, especially Bahrain and Qatar, saw revolts against the Abbasid Caliphate around 868. Mohammed ibn Ali, a revolutionary, led people in Bahrain and Qatar in a rebellion. It failed, and he moved to Basra. He later successfully started the Zanj Rebellion.

A group called the Qarmatians created a special republic in Eastern Arabia in 899. They thought the pilgrimage to Mecca was just a superstition. Once they controlled Bahrain, they attacked pilgrim routes across the Arabian Peninsula. In 906, they attacked a pilgrim caravan returning from Mecca and killed 20,000 pilgrims.

Qatar is mentioned in a book from the 1200s by the Muslim scholar Yaqut al-Hamawi. He wrote about the Qataris' fine striped woven cloaks and their skill in making and finishing spears, known as khattiyah spears. These spears were named after the Al-Khatt region, which included modern-day Qatif, Uqair, and Qatar.

After the Islamic Golden Age

Usfurids and Ormus Control (1253–1515)

The Usfurids controlled much of Eastern Arabia in 1253. But later, in 1320, the prince of Ormus took control of the region. Qatar's pearls were a major source of money for the Ormus kingdom. The Portuguese defeated the Ormus in 1507 after destroying their fleet. However, the Portuguese captain's forces rebelled, and he had to leave the Ormus island. Finally, in 1515, King Manuel I killed the Sultan's chief minister, forcing the Sultan to become a subject of King Manuel.

Portuguese and Ottoman Control (1521–1670)

The Portuguese took over Bahrain and mainland Qatar in 1521. They built many forts along the Arabian Coast. However, no major Portuguese ruins have been found in Qatar. The Portuguese focused on building a trading empire in Eastern Arabia, exporting gold, silver, silks, and pearls. In 1550, the people of Al-Hasa willingly accepted the rule of the Ottomans, preferring them to the Portuguese.

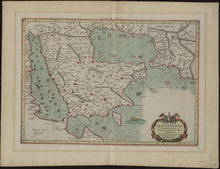

Gasparo Balbi, a Venetian merchant, was the first to mention Qatar in a printed book in the West. His book, Viaggio dell’Indie Orientali Balbi, described his travels to the Far East from 1579 to 1588. In it, he mentions a place called 'Barechator', which is thought to be a changed version of Bar Qatar, meaning mainland Qatar.

After the Portuguese were forced out of the area in 1602 by the Dutch and British, the Ottomans didn't see a need to keep many soldiers in the Al-Hasa region. As a result, the Bani Khalid tribe expelled the Ottomans in 1670.

Rule of Bani Khalid (1670–1783)

After expelling the Ottomans, the Bani Khalid tribe ruled Qatar from 1670. In 1766, the Utub clans of Al Jalahma and Al Khalifa moved from Kuwait to Zubarah in Qatar. When they arrived, the Bani Khalid had weak control over Qatar. After the Persian takeover of Basra in 1777, many merchants and families moved from Basra and Kuwait to Zubarah. This made the town a busy center for trade and pearling in the Persian Gulf.

By 1783, the Al Khalifa claimed Qatar and Bahrain. The Bani Khalid's control of nearby Al-Hasa officially ended in 1795.

Al Khalifa and Saudi Control (1783–1868)

After Persian attacks on Zubarah, the Utub and other Arab tribes drove the Persians out of Bahrain in 1783. The Al Jalahma tribe separated from the Utub alliance before Bahrain was taken. This left the Al Khalifa tribe in charge of Bahrain. They moved their main base from Zubarah to Manama. They still controlled the mainland and paid money to the Wahhabi to protect Qatar. However, Qatar didn't develop a strong central government because the Al Khalifa focused on Bahrain. So, Qatar had many 'temporary sheikhs', like Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah. By 1790, Zubarah was known as a safe place for merchants with full protection and no taxes.

From 1780, the town was threatened by the Wahhabi due to their attacks on Bani Khalid strongholds in Al-Hasa. The Wahhabi thought Zubarah's people might work against them with the Bani Khalid. They also believed the town's residents practiced beliefs different from Wahhabi teachings and saw Zubarah as an important way into the Persian Gulf. In 1787, Saudi general Sulaiman ibn Ufaysan led an attack on the town. Five years later, a large Wahhabi force conquered Al Hasa, sending many refugees to Zubarah. Wahhabi forces attacked Zubarah and nearby settlements in 1794 for helping these refugees. Local leaders could still manage things but had to pay taxes.

After defeating the Bani Khalid in 1795, the Wahhabi were attacked from two sides. The Ottomans and Egyptians attacked from the west, while the Al Khalifa in Bahrain and the Omanis attacked from the east. The Wahhabi teamed up with the Al Jalahmah tribe in Qatar, who then fought the Al Khalifa and Omanis.

In 1811, the Wahhabi leader moved his soldiers from Bahrain and Zubarah to fight the Egyptians in the west. Said bin Sultan of Muscat took this chance to attack the Wahhabi soldiers in Bahrain and Zubarah. The fort in Zubarah was burned, and the Al Khalifa family regained power.

British Involvement in the Gulf

Britain wanted safe passage for its East India Company ships, so it started to control the Persian Gulf. In 1820, the East India Company and the local rulers signed the General Maritime Treaty. This agreement recognized British authority and aimed to stop piracy and the slave trade. Bahrain signed the treaty, and it was assumed that Qatar, as a dependent area, was also included.

A report from 1820 by Major Colebrook gave the first descriptions of Qatar's main towns. All the coastal cities mentioned were near the Persian Gulf pearl beds and had been pearling for thousands of years. Until the late 1700s, all major towns like Al Huwaila, Fuwayrit, Al Bidda, and Doha were on the east coast. Doha grew around Al Bidda, the largest of these towns. The people included nomadic and settled Arabs, and many slaves from East Africa. In 1821, an East India Company ship attacked Doha because its people were involved in piracy. They destroyed the town, forcing 300 to 400 people to flee.

A British survey in 1825 noted that Qatar had no central government and was ruled by local leaders. Doha was ruled by the Al-Buainain tribe. In 1828, an Al-Buainain member killed a Bahraini, leading the Bahraini ruler to imprison the killer. The Al-Buainain tribe rebelled, causing the Al Khalifa to destroy their fort and force them out of Doha. This gave the Al Khalifa more control over Doha.

Conflicts Between Bahrain and Saudi Arabia

To keep an eye on the Wahhabi, Bahrain sent a government official, Abdullah bin Ahmad Al-Khalifa, to Qatar's coast in 1833. He turned against the Bahrainis and encouraged the people of Al Huwailah to rebel against the Al Khalifa and talk with the Wahhabi in 1835. Soon after, a peace deal was signed, and Al Huwailah was destroyed, its residents moved to Bahrain. However, Abdullah bin Ahmed's nephews quickly broke the deal by encouraging the Al Kuwari tribe to attack Al Huwailah.

The people of Qatar were caught in fights between the Bahraini ruler's forces and the Egyptian military commander of Al-Hasa. In late 1839 or early 1840, the governor of Al-Hasa sent troops to destroy Qatar because the Al Nuaim tribe of Zubarah refused to pay taxes. But the expedition ended early when a governor in Hofuf was killed.

In 1847, Abdullah bin Ahmed Al Khalifa and a Qatari chief named Isa bin Tarif teamed up against Mohammed bin Khalifa, the ruler of Bahrain. In November, bin Khalifa landed in Al Khor with 500 soldiers and help from Qatif and Al-Hasa. The opposing forces had 600 soldiers, led by bin Tarif. On November 17, a big battle, known as the Battle of Fuwayrit, happened. Bin Tarif and eighty of his men were killed, and his forces were defeated. After winning, bin Khalifa destroyed Al Bidda and moved its people to Bahrain. He sent his brother, Ali bin Khalifa, to Al Bidda. However, Ali had no real power, and local tribal leaders still managed Qatar's internal affairs.

In February 1851, the Wahhabi leader Faisal bin Turki left his base in Najd with soldiers, planning to invade Bahrain. Mohammed bin Khalifa offered peace, but Faisal refused. Ali bin Khalifa went to Qatar to get military help, but Mohammed bin Thani was convinced to support Faisal's forces when they reached Al Bidda in May. On June 8, forces loyal to Al Thani took an important tower near Ali bin Khalifa's home in Al Bidda Fort. This made Bahrain start talks with the British for a protection treaty to stop Faisal. They failed at first, but the British changed their mind after a report on the conflict and quickly sent a naval blockade to Manama. A peace treaty was signed on July 25, 1851. The Bahraini ruler agreed to pay 4,000 German krones to get back the Al Bidda Fort and for the Wahhabi to leave Qatar's people alone.

Economic Problems and British Influence

In 1852, Faisal bin Turki angered Mohammed bin Khalifa by giving safe haven to Abdullah bin Ahmed's sons in Dammam. Because of this, the Bahrainis tried to force out residents of Al Bidda and Doha who they thought were loyal to the Wahhabi. They did this by stopping them from pearl hunting. This blockade lasted until the end of the year. In February 1853, the Wahhabi started marching from Al-Hasa to Al Khor. After Qatar promised not to help the Wahhabi, Bahrain sent Ali bin Khalifa to the mainland to work with the local resistance. A peace agreement was reached in 1853 with British help.

Fights started again in 1859 when the Bahraini ruler stopped paying taxes to the Wahhabi leader. This was because the Wahhabi were helping Bahraini fugitives in Dammam. The Bahraini ruler also encouraged Qatari tribes to attack Wahhabi subjects. When Abdullah bin Faisal threatened to attack Bahrain, the British navy sent a ship to Dammam to stop any attacks. The situation got worse in May 1860 when Abdullah threatened to take over Qatar's coast until the yearly tax was paid. In May 1861, Bahrain signed a treaty with the British government. Britain agreed to protect Bahrain and recognized Qatar as dependent on Bahrain. In February 1862, the treaty was approved by the Indian government.

After Britain got involved, the Al Khalifa tribe's power over Qatar began to weaken. In 1863, Gifford Palgrave described Mohammed bin Thani as the recognized ruler of the Qatar Peninsula. In April 1863, the Bahraini ruler forced some people from Al Wakrah to leave because they were thought to be linked to the Wahhabi. The town's chief was also arrested for a similar reason. In 1866, a British report showed that Qatar was paying a yearly tax of 4,000 German krones to the Wahhabi, which went against the 1861 British treaty. The report also said that the Al Khalifa were taxing the people of Qatar for the same payment.

Qatari–Bahraini War

In June 1867, a representative of Mohammed Al Khalifa arrested a Bedouin from Al Wakrah and sent him to Bahrain. Mohammed bin Thani demanded his release, but the representative refused. This led Mohammed bin Thani to expel him from Al Wakrah. When Mohammed Al Khalifa heard this, he released the Bedouin and said he wanted peace talks. Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, Mohammed bin Thani's son, went to Bahrain to negotiate. He was imprisoned upon arrival. Soon, many ships and troops were sent to punish the people of Al Wakrah and Al Bidda. Abu Dhabi joined Bahrain because they thought Al Wakrah was a hiding place for people fleeing Oman. Later that year, the combined forces attacked the two Qatari cities with 2,000 men. This became known as the Qatari–Bahraini War. A British record later said that "the towns of Doha and Wakrah were, at the end of 1867, temporarily wiped out, with houses taken apart and people moved away." In June 1868, Qatari tribes fought back against Bahrain. A battle happened where 60 boats were sunk and 1000 men were killed. Afterward, the Bahraini ruler agreed to free Jassim bin Mohammed in exchange for captured Bahraini prisoners.

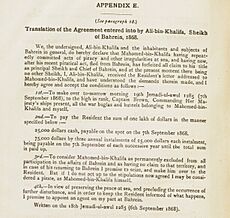

The joint attack by Bahrain and Abu Dhabi, and Qatar's counterattack, led the British political agent, Colonel Lewis Pelly, to make a peace agreement in 1868. Pelly's visit to Bahrain and Qatar and the resulting treaty were very important for Qatar's history. It quietly recognized that Qatar was separate from Bahrain and clearly acknowledged Mohammed bin Thani as an important leader of Qatar's tribes.

Ottoman Control (1871–1913)

The Ottoman Empire expanded into Eastern Arabia in 1871. After settling on the Al-Hasa coast, they moved towards Qatar. Al Bidda soon became a base for Bedouins bothering the Ottomans in the south. Abdullah II Al-Sabah of Kuwait was sent to the town to help Ottoman troops land. He brought four Ottoman flags for the most important people in Qatar. Mohammed bin Thani received and accepted one flag, but he sent it to Al Wakrah and kept his local flag flying over his house. Jassim bin Mohammed accepted a flag and flew it over his house. A third flag was given to Ali bin Abdul Aziz, the ruler of Al Khor.

The British didn't like the Ottoman advances because they felt their interests were at risk. When their objections were ignored, the British gunboat Hugh Rose arrived in Qatar on July 19, 1871. Sidney Smith, the assistant British official in the Persian Gulf, found that Qatar flew the flags willingly. To make things worse for the British, Jassim bin Mohammed, who had taken over his father's role, allowed the Ottomans to send 100 troops and equipment to Al Bidda in December 1871. By January 1872, the Ottomans included Qatar in their territory. It became a province in Najd. Jassim bin Mohammed was made the local governor, and most other Qataris kept their positions in the new government.

Charles Grant, the assistant British official, wrongly reported that the Ottomans sent 100 troops from Qatif to Zubarah in August 1873. The ruler of Bahrain was unhappy because the Al Nuaim tribe in Zubarah had signed a treaty to be his subjects. When the ruler confronted Grant, Grant told him to talk to Edward Ross, another British official. Ross told the ruler he didn't think he had the right to protect tribes in Qatar. In September, the ruler repeated his claim over the town and tribe. Grant argued that no treaties with Bahrain specifically mentioned the Al Nuaim or Zubarah. A British government official agreed, saying the ruler of Bahrain "should, as much as possible, avoid getting involved in problems on the mainland."

Another chance for the Al Khalifa to claim Zubarah came in 1874 after an opposition leader named Nasir bin Mubarak moved to Qatar. They believed Mubarak, with Jassim bin Mohammed's help, would target the Al Nuaim in Zubarah as a step towards an invasion. So, Bahrain sent more soldiers to Zubarah. The British disapproved, saying the ruler was getting involved in problems. Edward Ross made it clear that a government decision advised the ruler not to interfere in Qatar's affairs. The Al Khalifa stayed in touch with the Al Nuaim, taking 100 members of the tribe into their army and offering money. Jassim bin Mohammed expelled some members of the tribe after they attacked ships near Al Bidda in 1878.

Even though many important Qatari tribes were against it, Jassim bin Mohammed continued to support the Ottomans. However, their partnership didn't improve. Relations got worse when the Ottomans refused to help Jassim in his expedition to Abu Dhabi-controlled Khawr al Udayd in 1882. Also, the Ottomans supported Mohammed bin Abdul Wahab, an Ottoman subject, who tried to replace Jassim bin Mohammed in 1888.

Battle of Al Wajbah

In February 1893, Mehmed Hafiz Pasha arrived in Qatar to collect unpaid taxes and address Jassim bin Mohammed's opposition to Ottoman government changes. Fearing he would be killed or imprisoned, Jassim bin Mohammed moved to Al Wajbah (10 miles west of Doha) with several tribe members. Mehmed demanded that he dismiss his troops and promise loyalty to the Ottomans. However, Jassim bin Mohammed refused to obey Ottoman authority. In March 1893, Mehmed imprisoned Jassim's brother, Ahmed bin Mohammed Al Thani, and 13 important Qatari tribal leaders on an Ottoman ship. After Mehmed refused an offer to release the captives for ten thousand liras, he ordered about 200 Ottoman troops to advance towards Jassim bin Mohammed's fort in Al Wajbah.

Soon after arriving at Al Wajbah, the Ottoman troops were heavily attacked by Qatari soldiers on foot and horseback, who numbered 3,000 to 4,000 men. They retreated to Shebaka fortress, where they again suffered losses from a Qatari attack. After they retreated to the Al Bidda fortress, Jassim bin Mohammed's advancing forces surrounded the fortress and cut off its water supply. The Ottomans gave up and agreed to release the Qatari captives in exchange for safe passage for Mehmed Pasha's cavalry to Hofuf by land. Although Qatar did not gain full independence from the Ottoman Empire, this battle led to a treaty that later helped Qatar become an independent country within the empire.

British Protectorate (1916–1971)

The Ottomans officially gave up their claim over Qatar in 1913. In 1916, the new ruler, Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani, signed a treaty with Britain. This made Qatar part of the trucial system. Qatar gave up control of its foreign affairs, like giving away land, in exchange for Britain's military protection from outside threats. The treaty also aimed to stop slavery, piracy, and gunrunning, but the British didn't strictly enforce these rules.

Even with British protection, Abdullah bin Jassim's position was not secure. Rebellious tribes refused to pay taxes. Unhappy family members plotted against him. He also felt vulnerable to Bahrain and the Wahhabi. The Al Thani family were merchant rulers, relying on trade, especially pearls. They depended on other tribes, mainly the Bani Hajer who were loyal to Ibn Saud, the ruler of Najd and Al-Hasa, to fight for them. Despite many requests from Abdullah bin Jassim for strong military support, weapons, and a loan, the British didn't want to get involved in inland affairs. This changed in the 1930s when the search for oil deals in the region became more intense.

Oil Discovery and Its Impact

The rush for oil made regional land disputes more serious and highlighted the need to set clear borders. The first step happened in 1922 at a border meeting in Uqair. A prospector named Major Frank Holmes tried to include Qatar in an oil deal he was discussing with Ibn Saud. Sir Percy Cox, the British representative, saw through this plan and drew a line on the map separating the Qatar Peninsula from the mainland. The first oil survey in Qatar took place in 1926, led by George Martin Lees, a geologist for the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, but no oil was found. The oil issue came up again in 1933 after oil was found in Bahrain. Lees had already noted that if this happened, Qatar should be checked again. After long talks, on May 17, 1935, Abdullah bin Jassim signed a 75-year oil deal with Anglo-Persian. He received 400,000 rupees when he signed and 150,000 rupees each year, plus royalties. As part of the deal, Great Britain made more specific promises of help than in earlier treaties. Anglo-Persian transferred the deal to Petroleum Development (Qatar) Ltd., a company under IPC.

In 1936, Bahrain claimed control over a group of islands between the two countries. The largest island was Hawar Islands, off Qatar's west coast, where Bahrain had a small military post. Britain accepted Bahrain's claim, despite Abdullah bin Jassim's objections. This was largely because the Bahraini ruler's British adviser could present their case in a legal way that British officials understood. In 1937, Bahrain again claimed the deserted town of Zubarah after a dispute involving the Al Nuaim tribe. Abdullah bin Jassim sent a large, well-armed force and defeated the Al Nuaim. The British official in Bahrain supported Qatar's claim and warned Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa, the ruler of Bahrain, not to use military force. Angry about losing Zubarah, Hamad ibn Isa placed a harsh ban on trade and travel to Qatar.

Drilling for the first oil well began in Dukhan in October 1938. Over a year later, oil was found in the limestone. Unlike the oil found in Bahrain, this was similar to Saudi Arabia's oil field discovered three years earlier. Oil production stopped between 1942 and 1947 because of World War II. The war caused food shortages, making Qatar's economic problems worse. These problems had started in the 1920s when the pearl trade collapsed and got worse in the early 1930s with the Great Depression and the Bahraini trade ban. As in past hard times, entire families and tribes moved to other parts of the Persian Gulf, leaving many Qatari villages empty. Abdullah bin Jassim went into debt and prepared his favorite second son, Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani, to take over when he retired. However, Hamad bin Abdullah died in 1948, leading to a problem over who would rule next. The main candidates were Abdullah bin Jassim's oldest son, Ali bin Abdullah Al Thani, and Hamad bin Abdullah's teenage son, Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani.

Oil exports and payments for offshore oil rights began in 1949. This was a turning point for Qatar. The oil money would completely change the economy and society. It would also become the focus of local disputes and foreign relations. Abdullah bin Jassim realized this when several relatives threatened armed opposition if they didn't get more money. Old and worried, Abdullah bin Jassim turned to the British. He promised to step down and agreed to an official British presence in Qatar in exchange for recognition and support for Ali bin Abdullah as ruler in 1949.

Under British guidance, the 1950s saw the development of government structures and public services. Ali bin Abdullah was at first unwilling to share power, which had been centered in his household, with a new government run mostly by outsiders. Ali bin Abdullah's growing money problems and his inability to control striking oil workers and difficult sheikhs made him give in to British pressure. The first official budget was created by a British adviser in 1953. By 1954, there were forty-two Qatari government employees.

Protests and Changes

Many protests against the British and the ruling family happened in the 1950s. One of the biggest protests was in 1956. It had 2,000 participants, mostly high-ranking Qataris who supported Arab nationalists and unhappy oil workers. During another protest in August 1956, people waved Egyptian flags and shouted anti-colonial slogans. In October 1956, protesters tried to damage oil pipelines in the Persian Gulf using a bulldozer. These events were major reasons for the British to set up a police force in 1949. The protests led Ali bin Abdullah to give the police his personal authority and support. This was a big change from his earlier reliance on his personal guards and Bedouin fighters.

Public services grew slowly in the 1950s. The first telephone exchange opened in 1953, the first water desalination plant in 1954, and the first power plant in 1957. A dock, a customs warehouse, an airstrip, and a police headquarters were also built. In the 1950s, 150 adult men from the ruling family received money from the government. Sheikhs also received land and government jobs. This kept them happy as long as oil money increased. However, when revenues dropped in the late 1950s, Ali bin Abdullah couldn't handle the family pressures. Unhappiness grew because he lived in Switzerland, spent a lot of money, and went on hunting trips in Pakistan. This was especially true among those who didn't get government money (non-Al Thani Qataris) and other branches of the Al Thani family who wanted more privileges. The amount of money received depended on age and closeness to the ruler.

Due to family pressures and poor health, Ali bin Abdullah stepped down in 1960. Instead of giving power to Khalifa bin Hamad, who had been named heir in 1948, he made his son, Ahmad bin Ali, the ruler. However, Khalifa bin Hamad gained a lot of power as the heir and deputy ruler, largely because Ahmad bin Ali spent much time outside the country. One of Khalifa's first actions was to increase funding for the sheikhs, reducing money for development projects and social services. In addition to allowances, adult male Al Thani members were given government jobs. This added to the unhappiness already felt by oil workers, lower-ranking Al Thani, and some government officials. These people formed the National Unity Front after a protester was fatally shot on April 19, 1963, by one of Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali's nephews. While the Saudi king was at the ruler's palace on April 20, 1963, a protest happened in front of the building. Police fired and killed three protesters, leading the National Unity Front to organize a general strike on April 21. The strike lasted about two weeks, affecting most public services.

The group made a statement that week with 35 demands for the government. These included less power for the ruling family, protection for oil workers, recognition of trade unions, voting rights for citizens, and more Arabs in leadership roles. Ahmed bin Ali rejected most of these demands and arrested about fifty of the most important National Unity Front members and supporters without trial in early May. The government also made some changes in response to the protests. These included giving land and loans to poor farmers, giving preference to Qatari citizens for jobs, and electing a municipal council.

The country's infrastructure, foreign workers, and government offices continued to grow in the 1960s, mostly under Khalifa bin Hamad's direction. There were also early attempts to make Qatar's economy more diverse, especially with a cement factory, a national fishing company, and small-scale farming. An official newspaper was first published in 1961, and in 1962, a nationality law was introduced. No cabinets existed during this time, but British and Egyptian advisers helped set up government departments, like the Department of Agriculture and a Department of Labor and Social Affairs.

Plans for a Federation

In 1968, Britain announced it would remove its military forces from east of Suez (including those in Qatar) within three years. Because the Persian Gulf states were small and vulnerable, the rulers of Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial Coast thought about forming a federation after the British left. The idea was first suggested in February 1968, when the rulers of Abu Dhabi and Dubai announced their plan to form a group and invited other Gulf states to join. Later that month, at a meeting with the rulers of Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial Coast, Qatar's government proposed forming a federation of Arab Emirates. It would be led by a higher council of nine rulers. This idea was accepted, and a declaration of union was approved. However, there were disagreements among the rulers about things like where the capital would be, how to write the constitution, and how to divide government ministries.

The rulers remained divided on many issues, even after Khalifa bin Hamad was elected chairman of the Temporary Federal Council in July 1968 and many ministries were set up. Two opposing groups quickly appeared. Qatar and Dubai teamed up against Bahrain and Abu Dhabi. Bahrain, supported by Abu Dhabi, tried to reduce the roles of other rulers in the union to gain leadership and power over their long-standing land disputes with Iran. The last meeting was in October 1969, when Zayed Al Nahyan and Khalifa bin Hamad were elected the first president and prime minister of the federation. Many issues were not resolved during the meeting, including the vice-president's position, the federation's defense, and whether a constitution was needed. Soon after the meeting, the British official in Abu Dhabi revealed Britain's interest in the meeting's outcome. This led Qatar and Ras al-Khaimah to withdraw from the federation because they felt there was foreign interference in their internal affairs. The federation then broke apart, despite efforts by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Britain to restart discussions.

Ahmad bin Ali then announced a temporary constitution in April 1970. It declared Qatar an independent Arab Islamic state with Sharia (Islamic law) as its main law. Khalifa bin Hamad was appointed prime minister in May. The first Council of Ministers was sworn in on January 1, 1970, and seven of its ten members were from the Al Thani family. Khalifa bin Hamad's ideas about the federation proposal won out.

Independence (1971–Present)

Qatar declared its independence on September 1, 1971, and became an independent state on September 3. When Ahmad bin Ali made the official announcement from his villa in Switzerland instead of his palace in Doha, many Qataris felt it was time for a change in leadership. On February 22, 1972, Khalifa bin Hamad removed Ahmad bin Ali from power while he was on a hunting trip in Iran. Khalifa bin Hamad had the quiet support of the Al Thani family and Britain, as well as political, financial, and military support from Saudi Arabia.

Unlike his predecessor, Khalifa bin Hamad reduced family allowances and increased spending on social programs, including housing, health, education, and pensions. He also filled many top government jobs with close relatives. In 1993, Khalifa bin Hamad was still the Emir, but his son, Hamad bin Khalifa, who was the heir and defense minister, had taken over much of the daily running of the country. The two consulted with each other on all important matters.

In 1991, Qatar played a big part in the Gulf War, especially during the Battle of Khafji. Qatari tanks drove through the town and provided support for Saudi Arabian troops fighting Iraqi soldiers. Qatar allowed Canadian coalition troops to use the country as an airbase for aircraft patrols. It also allowed air forces from the United States and France to operate in its territory.

On June 27, 1995, the deputy emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa, peacefully removed his father Khalifa from power. An unsuccessful attempt to overthrow him was made in 1996. The emir and his father are now reconciled, though some supporters of the counter-coup remain in prison. The emir announced his plan for Qatar to move towards democracy. He allowed more freedom for the press and local elections as a step towards future parliamentary elections. A new constitution was approved by public vote in April 2003 and became effective in June 2005. Economic, social, and democratic changes happened in the following years. In 2003, a woman was appointed to the cabinet as minister of education.

Qatar and Bahrain had disputes over who owned Hawar Islands since the mid-1900s. In 2001, the International Court of Justice decided that Bahrain owned Hawar Islands, while Qatar received control over smaller disputed islands and the Zubarah region on mainland Qatar. During the trial, Qatar provided the court with 82 fake documents to support its claims. These claims were later withdrawn after Bahrain discovered the forgeries.

In 2003, Qatar served as the US Central Command headquarters and one of the main starting points for the invasion of Iraq. In June 2013, Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa stepped down as emir and passed leadership to his son and heir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.

To manage the money from selling natural gas, the Qatar Investment Authority was created in 2005. In 2008, the government launched Qatar National Vision 2030. This plan provides a guide for Qatar's long-term development and identifies challenges and solutions.

Arab Spring and Military Actions (2010–Present)

Qatar played a role in the wave of protests and civil wars in the Arab world known as the Arab Spring. Moving away from its usual role as a mediator, Qatar supported several changing states and uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa.

During the first months of the Arab Spring, Qatar's largest media network, Al Jazeera, helped gather Arab support and shaped the stories of the protests. Qatar sent hundreds of ground troops to support the National Transitional Council during the 2011 Libyan Civil War. These troops were mainly military advisers and were sometimes called "mercenaries" by the media. Qatar also took part in the air campaign with other countries.

Qatar has been very active in the Syrian Civil War, which started in spring 2011. In 2012, Qatar announced it would start arming and funding the opposition. It was also reported that Qatar had funded the Syrian rebellion with "as much as $3 billion" over the first two years of the civil war.

Starting in 2015, Qatar has participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was removed from power after the Arab Spring uprisings.

Diplomatic Crises (2014–2021)

In March 2014, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Bahrain recalled their ambassadors from Qatar. This was a protest against Qatar's alleged involvement in funding groups and political parties in ongoing Middle Eastern conflicts. The three countries returned their ambassadors in November of that year after an agreement was reached.

On June 5, 2017, several countries led by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt (known as the 'Quartet') cut ties with Qatar. They also took several actions, like closing air, land, and sea borders to Qatar. Saudi Arabia also stopped Qatar's involvement in the war in Yemen. The Quartet said they took these actions because of alleged Qatari ties to 'terrorist groups' in the region. On January 5, 2021, almost four years after the start of the incident, it was announced that the two sides reached an agreement in a deal arranged by Kuwait and the United States.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Catar para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Catar para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |