History of Somalia facts for kids

Somalia (Soomaaliya) is a country in the Horn of Africa. Long ago, it was a very important place for trade with ancient civilizations. Many scholars believe it might be the famous ancient Land of Punt. During the Middle Ages, powerful Somali states and port cities like Mogadishu, Barawe, and Merca controlled trade in the region.

In the late 1800s, the Italian colonial empire took control of parts of the coast through agreements with local kingdoms. Italy fought a long war, called the Banadir Resistance, with Somalis in the southern parts, especially around Merca. Italy gained full control of the northeastern, central, and southern areas after fighting against the Majeerteen Sultanate and the Sultanate of Hobyo. This Italian rule lasted until 1941, when the British took over with a military government.

In 1950, the United Nations created the Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration. It was promised independence after 10 years. British Somaliland, which was independent for four days as the State of Somaliland, joined with the trust territory in 1960. Together, they formed the independent Somali Republic. This new country had a civilian government led by Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf. In 1969, the Supreme Revolutionary Council, led by Mohamed Siad Barre, took power without violence. They renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic. In 1991, the Somali Civil War divided the country. Even with new governments forming, Somalia remains divided, with Somaliland acting as an independent state.

Contents

- Ancient History of Somalia

- Medieval Somali States

- Early Modern Somalia

- 19th Century Changes

- 20th Century and Italian Rule

- "Italian Somalia" and World War II

- Path to Independence

- Somali Democratic Republic

- Somali Civil War

- Decentralization and Governance

- Recent History

- Important Dates in Somali History

- See also

Ancient History of Somalia

People have lived in Somalia for a very long time, since at least the Stone Age. The oldest signs of burial customs in the Horn of Africa are from cemeteries in Somalia, dating back to 4000 BC. Ancient tools found in the north show that people lived there during the Paleolithic period.

Experts believe the first people who spoke Afro-Asiatic languages arrived in the region during the Neolithic period. They might have come from the Nile Valley or the Near East. Other scholars think these languages developed right here in the Horn of Africa.

The Laas Geel cave complex near Hargeisa has amazing rock art that is about 5,000 years old. It shows wild animals and decorated cows. Other cave paintings in the northern Dhambalin region show one of the earliest pictures of a hunter on horseback. These paintings are in a special style and are from 1000 to 3000 BCE. There are also many cave paintings of real and mythical animals in Karinhegane, between Las Khorey and El Ayo. Each painting has writing below it, and they are thought to be about 2,500 years old.

The Land of Punt

Ancient structures like pyramids, tombs, ruined cities, and stone walls found in Somalia show that a smart civilization once lived on the Somali peninsula. Discoveries from digs in Somalia prove that this civilization traded a lot with Ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece starting around 2000 BCE. This supports the idea that Somalia and nearby areas were the ancient Land of Punt.

The people of Punt traded valuable goods like myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, ivory, and frankincense. They traded with Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese, and Romans through their ports. An Egyptian trip to Punt, sent by Queen Hatshepsut, is recorded on temple walls.

Somali Trading Cities

During the classical period, Somali city-states like Mosylon, Opone, and Malao had a busy trade network. They connected with merchants from Phoenicia, Egypt, Greece, Persia, and the Roman Empire. They used special Somali ships called beden to carry their goods.

After the Romans took over the Nabataean Empire, Somali and Arab merchants agreed to stop Indian ships from trading in Arabian ports. This protected their very profitable trade in the Red Sea and Mediterranean Sea. However, Indian merchants continued to trade in Somali ports, which were free from Roman control.

For centuries, Indian merchants brought large amounts of cinnamon from Sri Lanka and Indonesia to Somalia and Arabia. This was a secret kept by Somali and Arab merchants. Romans and Greeks thought cinnamon came from Somalia, but it was actually brought there by Indian ships. Somali and Arab traders then sold this cinnamon for much higher prices to North Africa, the Near East, and Europe. This made the cinnamon trade very profitable for Somali merchants.

Medieval Somali States

Islam arrived on the northern Somali coast very early, soon after the Hijra (the migration of Prophet Muhammad). The Masjid al-Qiblatayn mosque in Zeila dates back to the 7th century, making it the oldest mosque in Africa. In the late 800s, a historian wrote that Muslims lived along the northern Somali coast. He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in Zeila, suggesting the Adal Sultanate started around the 9th or 10th century. Adal often fought with its neighbor, Abyssinia.

During the Middle Ages, Arab immigrants came to Somaliland. This led to stories about Muslim sheikhs like Daarood and Ishaaq bin Ahmed, who are said to be the ancestors of the Darod and Isaaq clans. They supposedly traveled from Arabia to Somalia and married into local clans.

The first ruling family of the Sultanate of Mogadishu was started by Abubakr bin Fakhr ad-Din. Mogadishu became a powerful trading city-state. It was the first to use gold from mines in Sofala. For many years, Mogadishu was the most important city in the "Land of the Berbers," which was the Arab name for the Somali coast. A 12th-century historian wrote that Mogadishu was home to "Berbers," who were the ancestors of modern Somalis.

The conquest of Shoa led to a rivalry between the Christian Solomonids and the Muslim Ifatites. This caused many wars. Parts of northwestern Somalia came under Solomonic rule, especially during the reign of Amda Seyon I. Later, Emperor Dawit I or Yeshaq I captured and executed King Sa'ad ad-Din II of the Walashma dynasty in Zeila. After this war, a song was made praising the victory, which has the first written mention of the word "Somali." Sa'ad ad-Din II's family found safety in Yemen and planned their revenge.

His oldest son, Sabr ad-Din II, built a new capital called Dakkar and called himself the King of Adal. He continued the war against the Solomonic Empire. Even with a smaller army, he defeated the Solomonids and looted nearby areas. Many battles were fought, and Sultan Sabr ad-Din II successfully pushed the Solomonic army out of Adal. He died naturally and was followed by his brother Mansur ad-Din. Mansur invaded the Solomonic Empire's capital and, according to reports, killed the Emperor. He then faced a large Solomonic army and forced them to agree to a truce in his favor.

Later, Sultan Mansur and his brother Muhammad were captured by the Solomonids. Mansur was replaced by his youngest brother, Jamal ad-Din II. Sultan Jamal reorganized the army and defeated the Solomonic armies in several battles. Emperor Yeshaq I gathered a large army and invaded cities, but Jamal's soldiers pushed them back. Jamal then launched a successful attack, causing heavy losses to the Solomonids. Yeshaq was forced to retreat, and Jamal's forces pursued them, taking much gold.

Jamal sent his brother Ahmad to attack another province. Even with losses, Emperor Yeshaq continued to fight. Sultan Jamal advanced further into Abyssinia. However, when he heard of Yeshaq's plan to attack Adal, he returned and fought the Solomonic forces. It is said that Emperor Yeshaq died in this battle. Sultan Jamal ad-Din II became the most successful ruler of Adal. But he was assassinated around 1432 or 1433 and was replaced by his brother Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din. Sultan Badlay continued the campaigns and planned a major attack into the Ethiopian Highlands. He got money from other Muslim kingdoms, including Mogadishu. However, King Badlay died during an invasion. His son, Muhammad ibn Badlay, became sultan and sought support from the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt. Muhammad and the Solomonic ruler Baeda Maryam agreed to a truce, leading to a time of peace.

Early Modern Somalia

Sultan Muhammad was followed by his son Shams ad Din, and Emperor Baeda Maryam by his son Eskender. War broke out again. Emperor Eskender invaded Dakkar but was stopped by a large Adalite army. Adal continued to raid Christian lands under General Mahfuz, who invaded Christian territories every year. Emperor Na'od tried to defend his people but was also killed in battle by the Adalite army.

Around 1527, under the leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (also known as Gurey or Gragn, meaning "left-handed"), Adal invaded Abyssinia. Adalite armies, with weapons and help from the Ottomans, caused much damage in Ethiopia. Many churches and old writings were looted and burned. Adal's use of firearms, which were rare in Ethiopia, allowed them to conquer more than half of Ethiopia.

Ethiopia was saved by a Portuguese expedition led by Cristóvão da Gama. The Portuguese had been in the area looking for the legendary priest-king Prester John. They responded to Ethiopia's pleas for help and sent soldiers. A Portuguese fleet arrived in 1541. A force of 400 musketeers, led by Cristóvão da Gama, marched inland. They were successful at first but were later defeated, and their commander was captured and killed. However, on February 21, 1543, a combined Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Muslim army, and Ahmed Gurey was killed. Ahmed Gurey's widow married his nephew Nur ibn Mujahid, who promised to avenge Ahmed's death. Nur continued fighting and later killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia.

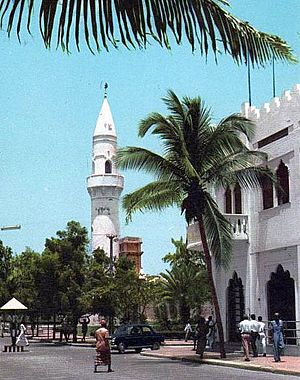

During the Ajuran period, the sultanates and cities of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, and Hobyo thrived. They had profitable trade with ships from Arabia, India, Venice, Persia, Egypt, Portugal, and even China. Vasco da Gama, who visited Mogadishu in the 1400s, noted it was a large city with tall houses and many mosques. In the 1500s, Duarte Barbosa wrote that many ships from India came to Mogadishu with cloth and spices. In return, they received gold, wax, and ivory. He also mentioned the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit, which made merchants very rich.

Mogadishu was a center for weaving special cloth called toob benadir, sold in Egypt and Syria. It also served as a stop for Swahili merchants and for the gold trade. Jewish merchants brought Indian textiles and fruit to the Somali coast for grain and wood. Trade with Malacca started in the 1400s, with cloth, ambergris, and porcelain as main goods. Giraffes, zebras, and incense were sent to China, making Somali merchants leaders in trade between Asia and Africa. Hindu merchants and Southeast African merchants used Somali ports like Merca and Barawa to trade safely, avoiding Portuguese and Omani interference.

In the 1500s, wars between Somalis and Portuguese in East Africa caused high tensions. The Portuguese were worried about Somali sailors working with Ottoman pirates. They sent many attacks against the Ajuran Empire to control Somali port cities. For example, the city of Barawa was attacked by a Portuguese fleet in 1507. In 1542, a Portuguese commander attacked Mogadishu, capturing an Ottoman ship and firing on the city. This made the sultan of Mogadishu sign a peace treaty with the Portuguese. He then sacked Barawa again and secured another peace agreement.

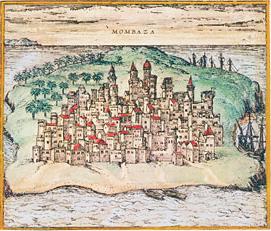

Ottoman-Somali cooperation against the Portuguese grew in the 1580s. Somali cities under Ajuran rule sympathized with Arabs and Swahilis under Portuguese rule. They sent a message to the Turkish pirate Mir Ali Bey for a joint attack against the Portuguese. He agreed and joined a Somali fleet, attacking Portuguese colonies in Southeast Africa. The Somali-Ottoman attack drove the Portuguese out of cities like Pate, Mombasa, and Kilwa. However, the Portuguese governor asked for a large fleet from India. This fleet arrived and turned the tide, retaking most lost cities and punishing their leaders. They did not attack Mogadishu.

Berbera, the main port of the Isaaq Sultanate, was the most important port in the Horn of Africa between the 1700s and 1800s. It had strong trade ties with ports in the Arabian Peninsula. The Somali and Ethiopian interiors relied heavily on Berbera for trade. In 1833, the port town grew to over 70,000 people, and more than 6,000 camels carrying goods arrived from inland in a single day. Berbera was the main market for goods like livestock, coffee, frankincense, myrrh, and gold.

A trade journal from 1856 described Berbera as "the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf." It noted that from November to April, a large fair took place, with caravans bringing goods like coffee, gum, ivory, and hides. Historically, the port of Berbera was controlled by the Reer Ahmed Nuh and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the Habar Awal.

19th Century Changes

In 1841, Haji Sharmarke Ali Saleh, a successful Somali merchant, took over Zeila using cannons and Somali soldiers. He removed the Arab ruler and became the leader of Zeila. Sharmarke quickly tried to control as much regional trade as possible, even looking towards Harar and the Ogaden. In 1845, he sent soldiers to take control of nearby Berbera from the local Somali leaders who were fighting among themselves.

Sharmarke's influence reached beyond the coast. He had many allies inland in Somalia and even in Abyssinia. Among his allies were the Sultans of Shewa. When the ruler of Harar arrested one of Sharmarke's agents, tensions rose. Sharmarke convinced the son of the Shewa ruler to imprison about 300 Harar citizens living in Shewa for two years.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started a golden age for his dynasty. In 1843, his army won a battle that brought stability to the region and boosted the East African ivory trade. He also had good relationships with leaders of nearby and distant kingdoms, such as the Omani and Yemeni sultans.

Sultan Ibrahim's son, Ahmed Yusuf, became sultan and was a very important person in 19th-century East Africa. He gathered 20,000 Somali troops, invaded, and captured the island of Zanzibar, defeating enemy troops and freeing enslaved people. Because of his strong military, Sultan Yusuf was able to collect payments from the Omani king in the coastal town of Lamu.

In northern and southern Somalia, the Gerad Dynasty traded with Yemen and Persia and competed with the Bari Dynasty. The Gerads and Bari Sultans built impressive palaces, castles, and forts. They had close ties with many empires in the Near East.

In the late 1800s, after the Berlin Conference, European powers started to divide Africa. This inspired leaders like Mohammed Abdullah Hassan and Sultan Nur Ahmed Aman in the north to gather support for resistance. Also, Sheikh Abikar Gafle started a resistance around Merca called the Banadir Resistance. Both the Banadir Resistance and the Dervish Movement began some of the longest fights against colonial rule in Africa.

The Mohammed Abdullah Hassan's Dervish movement spread into Somalia. They successfully pushed back the British Empire four times, forcing them to retreat to the coast. However, the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 by British air power.

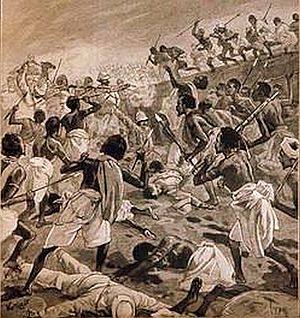

Banadir Resistance

In the 1890s, the Italian takeover of Marka angered the Bimal clan. Many joined the Bimal resistance against Italy. An Italian resident of the city was killed in 1904. In response, Italy occupied the port town of Jazira, south of Mogadishu. Bimal leaders then called for a large meeting, bringing together the Banadiri clans. This resistance became known as the Banadir Resistance. It was led by Sheikh Abdi Gafle and Ma’alin Mursal Abdi Yusuf, two important local Islamic teachers from the Bimal clan. The resistance started with clans but grew into a religious movement, mainly involving the Bimal, and later other clans.

Dervish Movement

News of an incident that sparked the Dervish rebellion was spread by Sultan Nur of the Habr Yunis. This incident involved a group of Somali children who were converted to Christianity by the French Catholic Mission in Berbera in 1899. Sultan Nur spread this news, leading to a religious rebellion that became the Somali Dervish movement. In a letter, Hassan said the British "have destroyed our religion and made our children their children." The Dervish movement opposed Christian activities, defending their version of Islam.

In his speeches, Hassan said that the British and Ethiopians were trying to take away the political and religious freedom of the Somali nation. He became a "champion of his country's political and religious freedom." Hassan declared that any Somali who did not support Somali unity and fight under his leadership would be considered an unbeliever. He got weapons from the Ottoman Empire and other Muslim countries. He also appointed ministers to manage different areas of Somalia. Hassan called for Somali unity and independence, organizing his followers into a military-style movement. It had a strict structure and was centralized. Hassan threatened to drive the Christians into the sea. He launched his first major attack with 1,500 Dervish soldiers and 20 modern rifles against British soldiers.

He pushed back the British in four expeditions and had good diplomatic relations with the Ottoman and German Empires.

20th Century and Italian Rule

In 1920, the Dervish movement ended after heavy British air attacks. Dervish territories became a protectorate. In the early 1920s, Italy's new fascist government changed its strategy. It planned to bring the northeastern sultanates into a "Greater Somalia." When Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi arrived on December 15, 1923, things began to change. Italy had agreements that protected these areas, but it did not rule them directly. The Fascist government only had direct rule over the Benadir territory. After the Dervish movement was defeated and fascism rose in Europe, Benito Mussolini gave De Vecchi permission to take over the northeastern sultanates on July 10, 1925. All old agreements were to be canceled.

Governor De Vecchi's first plan was to disarm the sultanates. But first, there needed to be enough Italian troops in both sultanates. To make his plan work, he started rebuilding the old Somali police force, the Corpo Zaptié, as a colonial force.

To prepare for the invasion, the Alula Commissioner was ordered in April 1924 to explore the territories. Even after 40 years of Italian presence, Italy did not know the geography well. A geological survey was planned, so the commissioner joined it.

The survey found that the Ismaan Sultanate (Majeerteen) relied on sea trade. If this trade was blocked, any resistance after the invasion would be small. As the first step, Governor De Vecchi ordered the two Sultanates to disarm. Both sultanates refused, saying it broke their protection agreements. This pressure made the two rival sultanates settle their differences and unite against their common enemy.

The Sultanate of Hobyo was different in its geography. It was founded by Yusuf Ali Kenadid in the mid-1800s in central Somalia. Its area stretched from Ceeldheer (El Dher) to Dhusamareb in the southwest, and from Galladi to Galkayo in the west.

By October 1, De Vecchi's plan was put into action. The invasion of Hobyo began in October 1925. Columns of the new Zaptié moved towards the sultanate. Hobyo, Ceelbuur (El Buur), Galkayo, and the surrounding area were taken over within a month. Hobyo became an administrative region. Sultan Yusuf Ali surrendered. However, suspicions arose when the Hobyo commissioner reported armed men moving towards the sultanate's borders. Before the Italians could focus on the Majeerteen, they faced new problems. On November 9, a rebellion, led by Omar Samatar, one of Sultan Ali Yusuf's military chiefs, recaptured El Buur. The rebellion quickly spread to the local people. The region revolted, and El-Dheere also came under Omar Samatar's control. The Italian forces tried to retake El Buur but were pushed back. On November 15, the Italians retreated and were ambushed, suffering many casualties.

While a third attempt was being prepared, the commander of the operation was ambushed and killed. Because of this, and two failed attempts to stop the El Buur rebellion, the Italian troops lost morale. The Governor took the situation seriously and asked for two battalions from Eritrea to help. He took charge of the operations. Meanwhile, the rebellion gained support across the country.

The fascist government was surprised by the problems in Hobyo. The whole plan of conquest was failing. The El-Buur incident changed Italy's strategy, reminding them of their defeat by Abyssinia. Also, officials in Rome doubted the Governor's ability. Rome told De Vecchi that he would get reinforcements from Eritrea, but the commander of those battalions would lead the military operations. De Vecchi was to stay in Mogadishu and handle other colonial matters.

While the situation was confusing, De Vecchi moved the deposed sultan to Mogadishu. Fascist Italy was determined to retake the sultanate. To weaken the resistance, and before the Eritrean reinforcements arrived, De Vecchi started to create distrust among the local people by buying their loyalty. This tactic worked better than military campaigns, and the resistance slowly weakened.

On the military front, Italian troops finally took El Buur on December 26, 1925. Omar Samatar's forces had to retreat.

With Hobyo under control, the fascists focused on the Majeerteen. In early October 1924, the new Alula commissioner gave King Osman Mahamuud an ultimatum to disarm and surrender. Italian troops began to enter the sultanate. When they landed at Haafuun and Alula, the sultanate's troops fired on them. Fierce fighting followed. To avoid more conflict, King Osman tried to talk to the Italians, but he failed. Fighting broke out again. On October 7, the Governor ordered the Sultan to surrender and seized all merchant boats in the Alula area to scare the people. At Hafun, all boats were destroyed.

On October 13, the commissioner was to meet King Osman to demand his surrender. King Osman was trying to buy time. However, on October 23, King Osman sent an angry reply, refusing the order. A full attack was ordered in November. Baargaal was bombed and destroyed. This region was united and far from the direct control of the Mogadishu government. The Italians faced strong resistance. In December 1925, led by Hersi Boqor, King Osman's son, the sultanate forces drove the Italians out of Hurdia and Hafun, two important coastal towns. Another group attacked and destroyed an Italian communication center at Cape Guardafui. In response, Italian warships bombed all major coastal towns of the Majeerteen. After a violent fight, Italian forces captured Eyl (Eil), which had been held by Hersi Boqor.

Italy called for more troops from its other colonies, especially Eritrea. When they arrived in late 1926, the Italians moved inland, where they had not been able to go before. Their attempt to capture Dharoor Valley was resisted and failed.

De Vecchi had to rethink his plans because he was facing humiliation. After a year of full effort, he still could not control the sultanate. Even though the Italian navy blocked the sultanate's main coastal entrance, they could not stop weapons from coming in. It was only in early 1927 that they finally closed the northern coast, cutting off arms and ammunition for the Majeerteen. By this time, the Italians had the upper hand. In January 1927, they attacked with a large force, capturing Iskushuban, in the heart of the Majeerteen. Hersi Boqor unsuccessfully attacked the Italians at Iskushuban. To discourage the resistance, ships were ordered to bomb the sultanate's coastal towns and villages. Inland, Italian troops took livestock. By the end of 1927, the Italians had full control of the sultanate. Hersi Boqor and his troops retreated to Ethiopia to rebuild their forces, but they could not retake their lands. This effectively ended the Campaign of the Sultanates.

"Italian Somalia" and World War II

On May 9, 1936, Mussolini announced the creation of the Italian Empire, calling it the Africa Orientale Italiana (A.O.I.). It included Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland (officially "Somalia italiana"). The Italians added the Ogaden region (taken from Ethiopia) to Somalia.

In the 1930s, the Italians invested a lot in building new roads and railways, like the "imperial road" between Addis Ababa and Mogadishu.

Many Somali soldiers fought in the Italian colonial army. These soldiers were part of the Italian Army's Infantry Division during World War II. The Zaptié police force provided security and acted as territorial police. By 1941, over 2,000 Zaptié soldiers, along with Italian Carabinieri, defended Culqualber in Ethiopia for three months until they were defeated by the Allies. After heavy fighting, the Somali troops and Italian Carabinieri received full military honors from the British.

In early 1940, 22,000 Italians lived in Somalia. The colony was one of the most developed in East Africa, especially in urban areas. More than 10,000 Italians lived in Mogadishu, the capital. New buildings were built in the Italian style. By 1940, Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi (now Jowhar) had 12,000 people, including nearly 3,000 Italian Somalis. It had factories for agriculture, like sugar mills.

In late 1940, Italian troops invaded British Somaliland and forced the British out. The Italians also took parts of British East Africa near Jubaland. Mussolini boasted that he had created "Greater Somalia" by uniting British Somaliland with his Somalia Governorate.

Path to Independence

During World War II, Britain regained control of British Somaliland and conquered Italian Somaliland. They governed both as protectorates. In November 1945, the United Nations gave Italy control of Italian Somaliland as a trust territory. This came with a promise that Somalia would become independent within ten years. This idea was first suggested by Somali political groups like the Somali Youth League (SYL). British Somaliland remained a British protectorate until 1960.

Because Italy held the territory under a UN plan, Somalis had the chance to learn about politics and self-government. British Somaliland, which would join the new Somali state, did not have these advantages. Even though British officials tried to improve the protectorate in the 1950s, it lagged behind. The differences in development and political experience between the two territories would cause problems when they united.

Britain also said that Somali nomads would keep their independence. But Ethiopia immediately claimed control over them. This led to Britain's unsuccessful attempt in 1956 to buy back the Somali lands it had given away. Britain also gave control of the mostly Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District (NFD) to Kenyan nationalists. This happened even though a vote showed that most people in the region wanted to join the new Somali Republic.

A vote was held in neighboring Djibouti (then called French Somaliland) in 1958, just before Somalia's independence in 1960. People voted on whether to join the Somali Republic or stay with France. The vote favored staying with France, mainly because of votes from the large Afar ethnic group and European residents. There were also claims of widespread cheating in the vote, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the vote. Most of those who voted "no" were Somalis who strongly wanted to join a united Somalia, as proposed by Mahmoud Harbi. Harbi died in a plane crash two years later. Djibouti finally became independent from France in 1977. Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali who had supported staying with France in 1958, became Djibouti's first president.

On July 1, 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic. The new country's borders were drawn by Italy and Britain. A government was formed with Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal. Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf became President of the Somali National Assembly. Aden Abdullah Osman Daar became the first President of the Somali Republic, and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke became Prime Minister (he later became president from 1967 to 1969). On July 20, 1961, the people of Somalia approved a new constitution through a vote. In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister. He later became the President of the self-governing Somaliland region in northwestern Somalia.

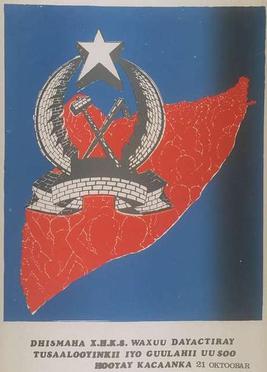

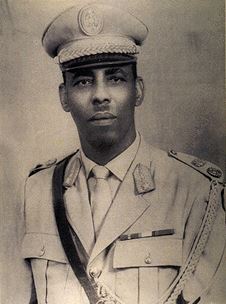

On October 15, 1969, while visiting the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot and killed by a policeman. His assassination was quickly followed by a military takeover on October 21, 1969 (the day after his funeral). The Somali Army took power without armed resistance. This takeover was led by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who was then the army commander.

Somali Democratic Republic

Supreme Revolutionary Council

After President Shermarke's assassination, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) took power. It was led by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye, and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye was called the "Father of the Revolution," and Barre soon became the head of the SRC. The SRC then renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic. They closed the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.

The new government started large public works projects. They also successfully ran campaigns to teach people to read and write, which greatly increased the number of people who could read. The new government also took control of industries and land. In foreign policy, they focused on Somalia's traditional and religious ties with the Arab world. Somalia joined the Arab League (AL) in 1974. That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which later became the African Union (AU).

In July 1976, Barre's SRC ended itself and created the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP). This was a one-party government based on scientific socialism and Islamic beliefs. The SRSP tried to combine the official state ideas with the official state religion. They focused on Muslim ideas of social progress, equality, and justice, which they said were at the heart of scientific socialism. The government also emphasized self-sufficiency, public participation, and direct ownership of production. While the SRSP allowed some private investment, the government's overall direction was mostly communist.

Ogaden War

In July 1977, the Ogaden War began. Barre's government wanted to include the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, which was mostly inhabited by Somalis, into a larger "Greater Somalia." In the first week of the war, Somali armed forces took control of the southern and central parts of the Ogaden. For most of the war, the Somali army won battles against the Ethiopian army. By September 1977, Somalia controlled 90% of the Ogaden and captured important cities. They also put pressure on Dire Dawa, threatening the train route to Djibouti.

After the siege of Harar, the Soviet Union sent a large and unexpected intervention. About 20,000 Cuban forces and thousands of Soviet experts came to help Ethiopia's communist government. By 1978, the Somali troops were pushed out of the Ogaden. This change in support from the Soviet Union made Barre's government look for new allies. They eventually turned to the United States, which had been interested in Somalia for some time. Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States allowed it to build the largest army in Africa.

Conflict and Displacement

During the late 1980s, Somalia experienced severe conflict and widespread violence, particularly affecting the Isaaq clan. This period led to significant destruction in cities like Hargeisa (90% destroyed) and Burao (70% destroyed). As a result, hundreds of thousands of Somalis, mainly from the Isaaq clan, were forced to leave their homes. About 500,000 people fled across the border to Ethiopia as refugees, creating one of the largest and fastest movements of people in Africa at the time. Another 400,000 people were displaced within Somalia. The scale of destruction in Hargeisa was so immense that it was compared to Dresden after World War II. These events happened during the Somali Civil War.

Rebellion

A new constitution was introduced in 1979, and elections for a People's Assembly were held. However, Barre's Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party still held power. In October 1980, the party was dissolved, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was brought back.

In May 1986, President Barre was seriously injured in a car accident near Mogadishu. He was treated in a hospital in Saudi Arabia for about a month. Lieutenant General Mohamed Ali Samatar, then Vice President, temporarily became the head of state. Although Barre recovered enough to run for re-election in December 1986, his poor health and age led to questions about who would take his place. Possible successors included his son-in-law, General Ahmed Suleiman Abdille, and Vice President Lt. Gen. Samatar.

By this time, Barre's government was becoming very unpopular. Many Somalis were unhappy with living under a military dictatorship. The government became more controlling. Resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia, started across the country. This eventually led to the Somali Civil War. These groups included the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), United Somali Congress (USC), Somali National Movement (SNM), and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM). There were also peaceful political opposition groups.

Somali Civil War

As the political situation worsened, Barre's long-standing government finally collapsed in 1991. The national army soon broke apart.

On December 3, 1992, the United Nations Security Council Resolution 794 was passed. It approved a group of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States. This force, called the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), was sent to ensure safety until humanitarian efforts could stabilize the situation. In 1993, the UN peacekeeping group started the two-year United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) mainly in the south to provide help.

Some armed groups that took power after Barre's government fell saw the UN troops as a threat. As a result, several gun battles took place in Mogadishu between local armed groups and peacekeepers. One of these was the Battle of Mogadishu, where US troops tried to capture a faction leader but were unsuccessful. The UN soldiers eventually left the country on March 3, 1995, after suffering many casualties.

Decentralization and Governance

After the civil war began and the central government collapsed, people in Somalia went back to local ways of solving problems. These included traditional customs or Islamic law. The legal system in Somalia now has three parts: civil law, religious law, and customary law.

Civil Law

Somalia's formal court system was mostly destroyed after the fall of the Siad Barre government. However, it was slowly rebuilt and managed by different regional governments, like the self-governing regions of Puntland and Somaliland. Later, for the Transitional Federal Government, a new temporary court system was created through international meetings.

Even with some political differences, these governments share similar legal structures. Many of these are based on the court systems of earlier Somali governments. These similarities in civil law include:

- A document that states Islamic shari'a (religious law) is most important, though in practice, shari'a is mainly used for things like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and family matters. The document also promises human rights for everyone. It ensures that judges are independent and protected by a special committee.

- A three-level court system: a supreme court, a court of appeals, and local courts (either divided into district and regional courts, or one court per region).

- The laws of the civilian government that were in place before the military takeover by the Barre government remain in effect until they are changed.

Shari'a Law

Islamic shari'a has always been a big part of Somali society. In theory, it has been the basis for all national laws in every Somali constitution. In practice, however, it only applied to common civil cases like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and family matters. This changed after the civil war started, when many new shari'a courts appeared in different cities and towns. These new courts do three things: they make decisions in criminal and civil cases, they organize a police force to arrest criminals, and they keep convicted prisoners locked up.

The shari'a courts are simple but have a typical structure: a chairman, vice-chairman, and four judges. A police force that reports to the court makes sure the judges' decisions are followed. They also help solve community problems and catch suspected criminals. The courts also manage prisons. An independent finance committee collects and manages taxes from local merchants.

Xeer (Customary Law)

For centuries, Somalis have used a form of traditional law called Xeer (pronounced "heer"). Xeer is a legal system where no single group or person decides what the law should be or how it should be understood.

The Xeer legal system is believed to have developed only in the Horn of Africa since about the 7th century. There is no sign that it developed elsewhere or was greatly influenced by any foreign legal system. Its legal words are almost all native, meaning they didn't come from other languages.

The Xeer legal system also requires different people to have special roles. So, you can find odayaal (judges), xeerbogeyaal (legal experts), guurtiyaal (detectives), garxajiyaal (lawyers), markhaatiyal (witnesses), and waranle (police officers) to make sure the law is followed.

Xeer has a few basic rules that never change. These rules include:

- Paying "blood money" for things like lying, stealing, hurting someone, or causing death. It also means helping relatives.

- Making sure different clans get along by treating women fairly, talking honestly with "peace messengers," and protecting certain groups like children, women, religious people, poets, messengers, sheikhs, and guests.

- Family duties, such as paying a dowry and rules for running away to get married.

- Rules about managing resources like pasture land, water, and other natural resources.

- Providing money to married female relatives and newly married couples.

- Giving livestock and other things to the poor.

Recent History

Transitional National Government

In 2000, Abdiqasim Salad Hassan was chosen as the President of the new Transitional National Government (TNG). This was a temporary government meant to lead Somalia to its third permanent government.

On October 10, 2004, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed was elected President of the next government, the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). He had helped create this temporary federal government earlier that year. He received 189 votes from the TFG Parliament. The previous President, Abdiqasim Salad Hassan, peacefully stepped down. Ahmed was sworn in a few days later on October 14, 2004.

Transitional Federal Institutions

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was the internationally recognized government of Somalia until August 20, 2012. It was set up as one of the temporary government bodies defined in the Transitional Federal Charter adopted in November 2004.

The TFG included the executive branch (the President and Cabinet), and the Transitional Federal Parliament was the law-making branch. The government was led by the President of Somalia, and the Cabinet reported to him through the Prime Minister. However, "TFG" was also used to refer to all three branches together.

Islamic Courts Union and Ethiopian Intervention

In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an Islamist group, took control of much of southern Somalia and quickly put Shari'a law into effect. The Transitional Federal Government wanted to regain its power. With help from Ethiopian troops, African Union peacekeepers, and air support from the United States, they managed to push out the ICU and strengthen their rule.

On January 8, 2007, TFG President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed entered Mogadishu for the first time since being elected. The government then moved its base to the capital from its temporary location in Baidoa. This was the first time since the fall of the Siad Barre government in 1991 that the federal government controlled most of the country.

After this defeat, the Islamic Courts Union split into different groups. Some more radical parts, including Al-Shabaab, regrouped to continue fighting against the TFG and the Ethiopian military in Somalia. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab won battles, taking control of important towns and ports in central and southern Somalia. By the end of 2008, the group had captured Baidoa. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other groups had forced the Ethiopian troops to leave. They left behind an African Union peacekeeping force to help the Transitional Federal Government.

Because of a lack of money and people, and an arms embargo that made it hard to rebuild a national security force, President Yusuf had to send thousands of troops from Puntland to Mogadishu to fight the armed groups in the south. The Puntland government provided money for this effort. This left little money for Puntland's own security forces and public workers, making the region vulnerable to piracy and attacks.

On December 29, 2008, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed announced his resignation as President of Somalia. He said he regretted failing to end the country's long conflict. He also blamed the international community for not supporting the government. He said the speaker of parliament would take over as president.

Coalition Government

Between May 31 and June 9, 2008, representatives from Somalia's federal government and a moderate Islamist group called the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) held peace talks in Djibouti. The talks ended with an agreement for Ethiopian troops to leave in exchange for an end to fighting. The Parliament was then expanded to 550 seats to include ARS members. They then elected Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, the former ARS chairman, as President. President Sharif soon appointed Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, the son of the assassinated former President, as the new Prime Minister.

With help from a small team of African Union troops, the coalition government started a counterattack in February 2009 to take full control of the southern half of the country. To strengthen its rule, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other ARS members, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi group. Also, Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam, the two main opposing Islamist groups, began fighting each other in mid-2009.

As a peace gesture, in March 2009, Somalia's coalition government announced it would bring back Shari'a as the nation's official legal system. However, fighting continued in the southern and central parts of the country. Within months, the coalition government lost control of over 80% of the disputed territory to the Islamist groups.

On October 14, 2010, diplomat Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed (Farmajo) was appointed the new Prime Minister of Somalia. The previous Prime Minister had resigned after a disagreement with President Sharif over a proposed constitution.

According to the Transitional Federal Government's (TFG) Charter, Prime Minister Mohamed named a new Cabinet on November 12, 2010. This new Cabinet was praised by the international community. The number of ministerial positions was greatly reduced from 39 to just 18. Only two ministers from the previous Cabinet were reappointed. Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi group and an important ally of the TFG, was given the key Interior and Labor ministries. The other positions were mostly given to experts new to Somali politics.

In its first 50 days, Prime Minister Mohamed's new government paid its first monthly salaries to government soldiers. They also started a system to register all security forces using fingerprints within four months. More members were appointed to the Independent Constitutional Commission to work with Somali legal experts, religious scholars, and cultural experts on the nation's new constitution. This was a key part of the government's plans. High-level federal groups were also sent to calm tensions between clans in several regions. To improve transparency, Cabinet ministers fully shared their assets and signed a code of ethics.

An Anti-Corruption Commission was also set up. It had the power to investigate and review government decisions to monitor public officials more closely. Also, unnecessary trips abroad by government members were stopped, and all travel by ministers now needed the Prime Minister's approval. A budget for 2011's federal spending was approved by parliament, with paying civil service employees as a top priority. A full check of government property and vehicles is also being done. In the war, the new government and its allies also managed to gain control of 60% of Mogadishu, where most of the capital's population now lives. With more troops, the pace of gaining territory is expected to speed up.

On June 19, 2011, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed resigned as Prime Minister of Somalia. This was part of the Kampala Accord, an agreement that also extended the terms of the President, Parliament Speaker, and Deputies until August 2012, when new elections would be held. Abdiweli Mohamed Ali, Mohamed's former Minister of Planning, was later named permanent Prime Minister.

Federal Government

As part of the "Roadmap for the End of Transition," a plan to create lasting democratic institutions in Somalia, the Transitional Federal Government's temporary term ended on August 20, 2012. The Federal Parliament of Somalia was then officially started, bringing in the Federal Government of Somalia. This was the first permanent central government in the country since the civil war began.

On September 10, 2012, parliament elected Hassan Sheikh Mohamud as the new President of Somalia. President Mohamud later appointed Abdi Farah Shirdon as the new Prime Minister on October 6, 2012. He was then replaced by Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed on December 21, 2013.

In April 2013, Hassan restarted national reconciliation talks between the central government in Mogadishu and the self-declared independent Somaliland authorities. The meeting, organized by the government of Turkey in Ankara, ended with an agreement between Hassan and Ahmed Mahamoud Silanyo, President of Somaliland. They agreed to fairly share development aid meant for Somalia and to work together on security.

In August 2013, the Somali federal government signed a national reconciliation agreement in Addis Ababa with the self-governing Jubaland administration in southern Somalia. This agreement was brokered by Ethiopia's Foreign Ministry after long talks. Under the agreement, Jubaland would be managed for two years by a temporary administration led by its current president. The regional president would lead a new Executive Council and appoint three deputies. Control of Kismayo's seaport and airport would be transferred to the Federal Government after six months. Money from these facilities would be used for Jubaland's services, security, and local development. Also, Jubaland's military forces would join the central command of the Somali National Army (SNA), and the temporary administration would command the regional police. The UN Special Envoy to Somalia called the agreement "a breakthrough that unlocks the door for a better future for Somalia."

In August 2014, the Somali government launched Operation Indian Ocean against the Al-Shabaab group to clear out remaining areas held by them.

On December 17, 2014, former Prime Minister Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke was reappointed Prime Minister.

In February 2015, Hassan led a three-day meeting in Mogadishu with the presidents of the Puntland, Jubaland, and South West State regional governments. Under the "New Deal for Somalia," Hassan held more national reconciliation talks with the regional leaders in Garowe in April and May. They signed a seven-point agreement in Garowe, allowing 3,000 troops from Puntland to immediately join the Somali National Army. They also agreed to include soldiers from other regional states into the SNA.

On February 8, 2017, Somali MPs elected former Prime Minister Mohamed Abdullahi "Farmajo" Mohamed in a surprising result. On February 23, 2017, President Mohamed appointed former humanitarian worker and businessman Hassan Khaire as his Prime Minister.

When President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed's term ended in February 2021, election dates for a successor had not been set. Fighting then broke out in Mogadishu. This fighting continued until May 2021, when the government and opposition agreed to hold elections within 60 days. After more talks, the presidential election was set for October 10.

In December 2021, Mohamed took away the Prime Minister's authority to organize elections and suggested a new committee should oversee them. This led the Prime Minister to accuse Mohamed of trying to stop the election process. On December 27, Mohamed announced he was suspending the Prime Minister over claims of obstructing corruption investigations.

On May 15, 2022, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud was again elected as President of Somalia.

Important Dates in Somali History

Ancient Times

- c. 2350 BC: The Land of Punt starts trading with the Ancient Egyptians.

- 1st century AD: City-states on the Somali coast actively trade with Greek and later Roman merchants.

Muslim Era

- 630s–900: Somalis adopt Islam.

- 9th century – 13th century: The Adal Kingdom exists.

- 10th century – 16th century: The Sultanate of Mogadishu is powerful.

- 1285–1415: The rise and fall of the Sultanate of Ifat.

- 1200s – late 1600s: The rise and fall of the Ajuran Sultanate.

- 1300–1400: Mogadishu, Zeila, and Barawe are visited by famous travelers like Ibn Battuta and Zheng He.

- 1415–1559: The rise and fall of the Adal Sultanate.

- 1528–1535: A holy war against Ethiopia is led by Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (also called Ahmed Gurey).

- late 17th – late 19th century: Berbera dominates trade in the Gulf of Aden. Haji Sharmarke Ali Saleh governs Zeila, Berbera, and Tadjourah. The Sultanate of the Geledi is also strong.

- mid-18th century – 1929: The Majeerteen Sultanate exists.

- 1878–1927: The Sultanate of Hobyo exists.

Modern Era

- July 20, 1887: British Somaliland becomes a protectorate (in the north).

- August 3, 1889: The Benadir Coast becomes an Italian Protectorate (in the northeast).

- 1895–1920: The Darawiish resistance takes place.

- March 16, 1905: Italian Somaliland becomes a colony (in the northeast, central, and south).

- July 1910: Italian Somaliland becomes a crown colony.

- 1920: The Dervish leader Mohammed Abdullah Hassan dies, ending a long colonial resistance war.

- January 15, 1935: Italian Somaliland becomes part of Italian East Africa, along with Italian Eritrea (and from 1936, Ethiopia).

- June 1, 1936: The Somalia Governorate is created as one of six parts of Italian East Africa.

World War II

- August 18, 1940: Italy occupies British Somaliland.

- February 1941: British administration takes over Italian Somaliland.

Independence and Cold War

- April 1, 1950: Italian Somaliland becomes a United Nations trust territory, promised independence within 10 years.

- June 26, 1960: British Somaliland gains independence as the State of Somaliland, planning to reunite with Italian Somaliland.

- July 1, 1960: British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland unite to form the Somali Republic.

- July 1, 1960: Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf becomes the first president of the Somali National Assembly.

- July 1, 1960 – 1967: Aden Abdullah Osman Daar is President.

- 1967–1969: Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke is President; he is assassinated.

- October 21, 1969: The Somali Democratic Republic is established.

- 1969–1991: Siad Barre, leader of the Supreme Revolutionary Council, rises to power.

- July 23, 1977 – March 15, 1978: The Ogaden War takes place.

- 1982: The 1982 Ethiopian–Somali Border War occurs.

- 1986: Barre's government begins to fall.

- 1991: Somaliland declares independence from Somalia.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Somalia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Somalia para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |