History of Washington, D.C. facts for kids

The story of Washington, D.C. is closely linked to its role as the capital of the United States. Long ago, the area along the Potomac River was home to the Algonquian-speaking Nacotchtank people. Later, President George Washington chose this spot for the new capital city.

During the War of 1812, British troops attacked the city in an event called the Burning of Washington. After the government returned, many public buildings, like the White House and the United States Capitol, had to be rebuilt. The McMillan Plan in 1901 helped make the downtown area beautiful, creating the National Mall with its many monuments and museums.

Washington, D.C., has always had a large Black population. Because of this, it became a major center for African-American culture and the Civil Rights Movement. For a long time, the city was managed by the U.S. federal government. This meant that Black and White school teachers were paid the same, like other federal workers. However, in 1913, during the time of President Woodrow Wilson, federal offices and workplaces became segregated, meaning Black and White people were kept separate. This separation continued for many decades.

Today, D.C. shows many differences. Some areas, especially east of the Anacostia River, have more people with lower incomes. After World War II, many middle-income White families moved to newer, more affordable homes in the suburbs. This move was made easier by new highways. In 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., there were major riots in mostly Black neighborhoods. Large parts of the city remained damaged for many years.

In contrast, areas west of Rock Creek Park, like Georgetown and Chevy Chase, are some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the country. In the early 1900s, the U Street Corridor was a very important place for African American culture. The Washington Metro subway system opened in 1976. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a growing economy and gentrification (when wealthier people move into an area) helped many downtown neighborhoods become lively again.

According to the U.S. Constitution, Congress has special control over the District of Columbia, which is not a state. Because of this, people living in Washington, D.C., have historically lacked voting representation in Congress. In 1961, the Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution gave the District three electoral votes, allowing its residents to vote for president and vice president. The District of Columbia Home Rule Act in 1973 gave the local government more power, including allowing residents to directly elect their city council and mayor.

Contents

Early History of the Area

Archaeologists believe that Native American groups lived in this area at least 4,000 years ago, especially around the Anacostia River. European explorers, like Captain John Smith, arrived in the early 1600s. At that time, the Patawomeck and Doeg tribes lived on the Virginia side of the Potomac River. The Piscataway tribe, also known as Conoy, lived on the Maryland side. The Nacotchtank people, connected to the Conoy, lived within what is now Washington, D.C.

The first European landowners in the area received land grants in the 1660s. As more European settlers arrived, they often had conflicts with Native Americans over land. In 1697, Maryland authorities built a fort in the area. The Conoy tribe moved west in 1697 and again in 1699.

Georgetown was founded in 1751 when the Maryland General Assembly bought land for the town. Alexandria, Virginia was founded in 1749. Georgetown was important because it was the farthest point up the Potomac River that large ships could reach. This made it a busy port for trading goods like tobacco. The Old Stone House, built in Georgetown in 1765, is the oldest building still standing in the District. Georgetown University was founded in 1789, attracting students from far away.

Founding the Capital City

Choosing the Location

The United States capital was first in Philadelphia. In 1783, a group of angry soldiers demanded payment for their service in the American Revolutionary War. When the governor of Pennsylvania refused to protect Congress from the protesters, Congress had to leave Philadelphia. This event showed that the national capital needed to be safe and separate from any single state.

So, the U.S. Constitution gave Congress the power to create a special district, "not exceeding ten Miles square" (100 square miles), to be the seat of the government. This district would be under Congress's direct control.

Northern states wanted the capital in a northern city, while Southern states wanted it closer to their agricultural areas. A deal was made between James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton. Southern states agreed to help the federal government take on the debts from the Revolutionary War. In return, the capital would be located in the South, along the Potomac River, which was the border between Maryland and Virginia, both slave states.

Maryland and Virginia agreed to give up land for the new capital. On July 16, 1790, the Residence Act was signed. It said the capital would be on the Potomac River, between the "Eastern-Branch" (now the Anacostia River) and the Conococheague Creek. President George Washington wanted to include Alexandria, Virginia, in the district. So, the Residence Act was changed in 1791 to allow this. However, it also said that all public buildings had to be built on the Maryland side of the river.

The chosen site was just below the "fall line" on the Potomac, the farthest point inland that boats could travel. It included the ports of Georgetown and Alexandria. Landowners in the area, like David Burns, eventually agreed to sell their land for the new city.

In September 1791, the three commissioners appointed by President Washington decided to name the federal district the Territory of Columbia and the federal city the City of Washington.

Major Andrew Ellicott, with the help of his team including Benjamin Banneker, surveyed the boundaries of the 100-square-mile district in 1791 and 1792. They placed forty sandstone boundary markers around the square. Thirty-six of these markers can still be seen today.

Designing the City

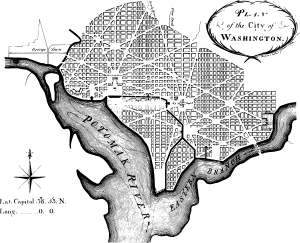

In early 1791, President Washington chose Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant to design the new city. L'Enfant created a plan with a grid of north-south and east-west streets. Wide, diagonal "grand avenues," named after the states, crossed this grid. Where these avenues met, L'Enfant planned open spaces like circles and plazas, which were later named after famous Americans.

L'Enfant's plan centered on the United States Capitol, which would sit on a hill called Jenkins Hill (now Capitol Hill). He also planned a very wide, garden-lined esplanade (now the National Mall) and a narrower avenue (Pennsylvania Avenue) connecting the Capitol to the "President's house" (the White House).

L'Enfant also included a system of canals, using water from Tiber Creek and James Creek, to run through the city.

However, L'Enfant had disagreements with the commissioners. In February 1792, Andrew Ellicott revised L'Enfant's plan, making some minor changes. Soon after, President Washington dismissed L'Enfant. Ellicott's revised plan was then published and became the guide for the city's development.

In 1800, the government officially moved to the new city. In 1801, Congress took full control over the District. In 1802, the City of Washington got its own local government with a mayor appointed by the President.

19th Century Growth and Challenges

Early Development and the War of 1812

The District of Columbia needed money from Congress for improvements, but Congress was often slow to provide it. The Washington City Canal was built in 1810, connecting the Anacostia River to Tiber Creek. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O) also began construction in Georgetown in 1828, helping with trade.

During the War of 1812, British troops attacked Washington, D.C., in August 1814. After winning the Battle of Bladensburg, the British entered the city. They burned many important public buildings, including the White House, the U.S. Capitol, and the Treasury Building. President James Madison and the government had to flee. First Lady Dolley Madison famously helped save a painting of George Washington from the White House.

After the war, some people in the North wanted to move the capital back to Philadelphia, but Congress voted against it, and Washington, D.C., remained the capital.

Changes and the Civil War

The B&O opened a rail line to Washington in 1835, improving transportation. Later, Union Station opened in 1907 as the city's main train terminal.

Almost as soon as the city was founded, some residents in Alexandria County, south of the Potomac, wanted to rejoin Virginia. They had several reasons:

- Alexandria was a center for the slave trade, and people worried that slavery might be outlawed in the capital.

- Alexandria's economy was struggling compared to Georgetown.

- Federal offices were not allowed in Virginia.

After a vote, Congress agreed in 1846 to return the land south of the Potomac to Virginia. This area became Alexandria County, Virginia, which today includes parts of Alexandria city and all of Arlington County.

Washington, D.C., was a small city until the American Civil War began in 1861. President Abraham Lincoln created the Army of the Potomac to protect the capital, and thousands of soldiers came to the area. The federal government grew a lot to manage the war, causing the city's population to jump from 75,000 in 1860 to 132,000 in 1870.

Slavery was ended in the District on April 16, 1862, before Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation. This made Washington a popular place for freed slaves to gather.

The city was protected by many Union Army forts, which mostly kept the Confederate army away. One exception was the Battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864, where Union soldiers fought off Confederate troops. President Lincoln visited the fort during the battle, making it only the second time a U.S. President was under enemy fire.

On April 14, 1865, just after the war ended, President Lincoln was shot at Ford's Theatre by John Wilkes Booth. He died the next morning, the first American president to be assassinated.

Modernizing the City

By 1870, Washington had grown, but it still had dirt roads and poor sanitation. Some in Congress even suggested moving the capital again, but President Ulysses S. Grant refused.

To fix these problems, Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871. This act combined the cities of Washington and Georgetown into one District of Columbia and created a new territorial government. Alexander Robey Shepherd became governor in 1873 and started many large projects to modernize the city. However, he spent too much money, leading the city into debt. In 1874, Congress replaced the territorial government with a three-member Board of Commissioners, who would directly rule the District for nearly a century.

Motorized streetcars began service in 1888, helping the city grow beyond its original boundaries. In 1895, Georgetown was formally absorbed into Washington, D.C., and its streets were renamed. Eventually, the entire area became known as Washington, D.C.

In the early 1880s, the Washington City Canal, which had become a dirty sewer, was covered over. Some parts of the canal's history can still be seen today, like the lock keeper's house near Constitution Avenue.

Many important buildings were constructed during this time by architect Adolf Cluss, including the National Museum and the Agriculture Department. The Washington Monument, a tall tribute to George Washington, was finished in 1884.

20th Century: New Plans and Civil Rights

The McMillan Plan and Urban Changes

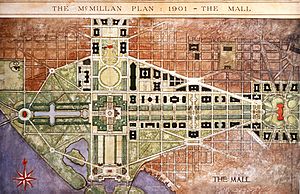

In 1901, the McMillan Commission created a new architectural plan for the National Mall. They were inspired by L'Enfant's original design and wanted to make Washington as grand as European capitals like Paris. This plan was part of the City Beautiful movement, which aimed to improve cities with beautiful, large buildings.

The McMillan Plan helped clear slums around the Capitol and replaced them with new monuments and government buildings. It also led to the construction of Union Station. Although World War I slowed things down, the plan was mostly completed with the building of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922.

Despite these improvements, many people in the early 1900s lived in poor housing. The Alley Dwelling Authority was created in 1934 to tear down slums and build affordable, modern homes.

President Woodrow Wilson, starting in 1913, brought segregation back to some federal departments. This meant Black and White employees were separated in workplaces, lunchrooms, and restrooms. This policy continued for decades. However, public school teachers, considered federal workers, were paid equally regardless of race. This attracted highly skilled teachers, especially to schools like Dunbar High School for African Americans.

In July 1919, during a period of violence across the country called Red Summer, White mobs attacked Black people in Washington. When police did not stop the attacks, the Black community fought back. Fifteen people were killed, and many more were injured.

In 1922, the Knickerbocker Storm brought heavy snow, causing the roof of the Knickerbocker Theater to collapse. Ninety-eight people died, making it the city's deadliest natural disaster.

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover ordered the United States Army to remove the "Bonus Army"—World War I veterans who had gathered in D.C. to ask for early benefits.

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, the city's population grew quickly as new federal agencies were created under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs. Many Federal Triangle buildings were built then.

World War II brought even more people to Washington, D.C., with over 300,000 new residents between 1940 and 1943. This led to a big housing shortage. The city's services struggled to keep up with the population growth. The The Pentagon was built nearby in Arlington to bring many federal defense offices together.

The Civil Rights Era

In 1944, Senator Theodore G. Bilbo tried to strengthen segregation in D.C.'s workplaces and parks. However, President Harry S. Truman ended racial discrimination in the Armed Forces and federal workplaces in 1948. Parks and recreation facilities in Washington remained segregated until 1954. Public schools were desegregated soon after.

A group of parents from the Anacostia neighborhood sued to have the John Philip Sousa Junior High admit both Black and White students. The Supreme Court ruled in Bolling v. Sharpe that all D.C. public schools had to be integrated. The Eisenhower administration made D.C. schools the first to integrate as an example for the rest of the country.

By 1957, Washington became the first major U.S. city with a majority African-American population. Many Black people had moved from the South during the Great Migration for jobs. In the years after the war, many White residents moved to the suburbs, helped by new highways.

On August 28, 1963, Washington was the center of the Civil Rights Movement with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech at the Lincoln Memorial. After King's assassination in 1968, riots broke out in Washington's Black neighborhoods. These events caused many White and middle-class Black residents to leave the city. Some neighborhoods showed the scars of these riots for decades.

Gaining Home Rule

The District of Columbia elects a delegate to the House of Representatives who can participate in committees but cannot formally vote. In 1961, the Twenty-third Amendment to the United States Constitution gave D.C. three electoral votes in presidential elections.

In 1973, Congress passed the District of Columbia Home Rule Act. This law gave the city more control over its own affairs, allowing residents to elect their own city council and mayor. Walter Washington became the first elected mayor of Washington, D.C.

The Washington Metro subway system opened its first section in 1976. New Metro stations helped bring new businesses and development to areas like Friendship Heights and Columbia Heights. The Kennedy Center also opened, along with new museums and monuments on the National Mall.

In 1978, Congress proposed an amendment to give D.C. full voting representation in Congress, like a state. However, not enough states approved it within the time limit.

The city's local government faced challenges, especially during the time of Mayor Marion Barry. In 1995, Congress created the District of Columbia Financial Control Board to oversee the city's spending and help it recover from financial problems. Mayor Anthony Williams, elected in 1998, led a period of economic growth and urban renewal. The District regained control of its finances in 2001.

21st Century: Recent Events and Changes

Statehood Movement

On November 8, 2016, Washington voters strongly supported a proposal to ask Congress to make the District the 51st State. Over 86% of voters approved this idea. However, challenges, including opposition in Congress, continue to make statehood difficult.

2021 Capitol Attack

In 2021, a group of demonstrators gathered in support of President Donald Trump. They later stormed and occupied the United States Capitol. Their goal was to stop Congress from officially counting the Electoral College votes and confirming Joe Biden's victory in the 2020 presidential election.

Changing Population

Washington, D.C., is seeing new population trends. The city's Black population has been decreasing as many African Americans move to the suburbs. At the same time, the city's White and Hispanic populations have been growing. Since 2000, there has been a 7.3% decrease in the African-American population and a 17.8% increase in the White population. Many African Americans are also moving to the South in a "New Great Migration" for family reasons, more opportunities, and lower living costs.