Domestication of the sheep facts for kids

The history of domestic sheep began a very long time ago, between 11,000 and 9,000 BC. This is when wild mouflon sheep were first tamed in ancient Mesopotamia. Sheep were among the very first animals that humans learned to live with and control. Early on, people raised these sheep mainly for their meat, milk, and skins. Later, around 6000 BC, people started to develop sheep with woolly coats. These woolly sheep were then brought to Africa and Europe through trading.

Contents

Where Did Sheep Come From?

It's a bit tricky to know the exact family tree of today's sheep and their wild ancestors. Most scientists think that our domestic sheep (called Ovis aries) came from the Asiatic mouflon (O. orientalis). Some sheep breeds, like the Castlemilk Moorit from Scotland, were even created by mixing domestic sheep with wild European mouflon.

Long ago, people thought the urial (O. vignei) might also be an ancestor of domestic sheep. This was because urials sometimes bred with mouflon in Iran. However, urials, argali (O. ammon), and snow sheep (O. nivicola) have a different number of chromosomes than other sheep. This means they probably aren't direct relatives. Studies comparing European and Asian sheep breeds show big genetic differences between them. This could mean there's an unknown wild sheep that helped create domestic sheep. Or, it could mean that humans tamed wild mouflon multiple times, leading to different types of sheep.

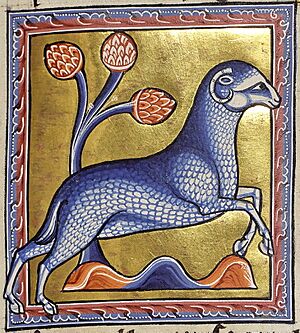

One big difference between ancient sheep and modern ones is how their wool was collected. Old sheep could be shorn (cut), but many could also have their wool pulled off by hand. This process is called "rooing." Rooing helped leave behind coarse fibers called kemps, which are longer than the soft fleece. Sometimes, the fleece was just collected from the ground after it fell off naturally. This "rooing" trait still exists in some old breeds today, like the Soay and many Shetland sheep. These Northern European breeds are small, have short tails, and often have horns on both males and females. They are very similar to ancient sheep.

At first, weaving and spinning wool was a home craft, not a big industry. People in Babylonia, Sumer, and Persia all relied on sheep. Even though linen was the first fabric for clothes, wool quickly became very valuable. Raising sheep for their fleece was one of the earliest industries. Flocks of sheep were even used as a way to trade goods in barter economies. Many important people in the biblical stories owned large flocks. People in the kingdom of Judea were even taxed based on how many rams they owned.

Sheep in Asia

How Sheep Were Tamed

Sheep were among the first animals tamed by humans. This happened between 11,000 and 8,000 BCE in Mesopotamia. They might have also been tamed separately in Mehrgarh, South Asia (now Pakistan), around 7,000 BCE. Wild sheep were good for taming because they weren't aggressive, were a manageable size, matured quickly, liked being in groups, and had many babies. Today, Ovis aries is a fully tame animal that mostly relies on humans to stay healthy and alive. Some feral (wild) sheep do exist, but only in places without big predators, usually on islands.

People started raising sheep for other things besides meat, milk, and skins in southwest Asia or western Europe. At first, sheep were only kept for these basic needs. But statues found in Iran suggest that people started choosing sheep for their woolly coats around 6000 BCE. The oldest woven wool clothes found are from two to three thousand years after that. Before woolly sheep, when a sheep was killed for meat, its hide was tanned and worn as a tunic (a simple garment). Researchers think that having such clothing helped humans live in much colder places than the Fertile Crescent, where it was usually warm. Sheep teeth and bones found at Çatalhöyük suggest that tame sheep lived there. By the Bronze Age, sheep with all the main features of modern breeds were common across Western Asia.

The people of an ancient village called Jeitun, from 6000 BCE, kept sheep and goats as their main farm animals. We also find signs of Nomadic pastoralism (people moving with their animals) at old sites. These sites have many sheep and goat bones, but not much grain or farming tools. They also have simple buildings and are located outside farming areas. This is similar to how modern nomadic herders live.

Modern Sheep Farming in Asia

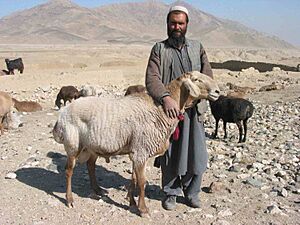

Middle East and Central Asia

A small but shrinking number of people in countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Afghanistan are nomadic or semi-nomadic herders. They move with their sheep and other animals.

India

In India, people are trying to improve their local desi sheep breed. They are mixing them with Merino and other sheep that produce high-quality wool. The goal is to create a desi sheep that gives both good wool and mutton (sheep meat).

China

Sheep are not a huge part of China's farming economy. Most of China doesn't have the large open fields needed for sheep farming. It's more common in the northwestern provinces where there are big open lands. China has its own sheep breed called the zhan. But its numbers have been going down since 1985, even though the government has tried to promote it.

Japan

The Japanese government encouraged farmers to raise sheep in the 1800s. They brought in sheep breeds like Yorkshire, Berkshire, Spanish merino, and many Chinese and Mongolian sheep. However, farmers didn't know enough about how to keep sheep successfully, and the government didn't give them enough information. So, the project failed and was stopped in 1888.

Mongolia

Sheep herding has been a main way of life and economy for Mongolians for thousands of years. Mongolian traditions and modern science for sheep herding are very advanced. Mongolians classify their sheep by wool length, thinness, and softness. They also look at how well sheep can survive at different heights, their looks, tail shape, size, and other things. The most common sheep breeds are Mongol Khalha, Gov-altai, Baidrag, Bayad, Uzenchin, and Sumber. All of these are fat-tailed breeds.

Every year, a count of all domestic animals in Mongolia is done. At the end of 2017, there were over 30 million sheep. This made up 45.5 percent of all the country's farm animals. Each year before the Lunar New Year, the government gives out a special award called "Best Herder" to chosen herders.

Sheep in Africa

Sheep arrived in Africa soon after they were tamed in western Asia. Some historians once thought sheep might have first come from Africa. This idea was based on old rock art and bones from Barbary sheep. The first sheep came to North Africa through the Sinai Peninsula. They were part of ancient Egyptian society between eight and seven thousand years ago. Sheep have always been important for farming in Africa. But today, the only country that keeps a lot of sheep for business is South Africa, with 28.8 million sheep.

In Ethiopia, there are many different types of sheep. People have tried to group them by tail shape and wool type. One person, H. Epstein, tried to classify them into 14 types based on these two things. However, in 2002, new genetic studies showed there are only four main types of Ethiopian sheep: short-fat-tailed, long-fat-tailed, fat-rumped, and thin-tailed.

Sheep in Europe

Sheep farming spread quickly in Europe. Digs show that around 6000 BCE, during the Neolithic period (New Stone Age), people called the Castelnovien, living near Marseille in France, were among the first in Europe to keep tame sheep. From its very beginning, ancient Greek civilization relied on sheep as their main farm animals. They even gave names to individual sheep. Sheep in Scandinavia, like those we see today with short tails and multi-colored wool, were also present early on.

Later, the Roman Empire kept sheep on a large scale. The Romans helped spread sheep raising across much of Europe. Pliny the Elder, in his book Natural History, wrote a lot about sheep and wool. He said, "Many thanks, too, do we owe to the sheep, both for pleasing the gods, and for giving us the use of its fleece." He then described the types of ancient sheep and the many colors, lengths, and qualities of their wool. Romans also started the practice of covering sheep with coats (today usually made of nylon) to keep their wool clean and shiny.

During the Roman rule of the British Isles, a large wool factory was built in Winchester, England, around 50 CE. By 1000 CE, England and Spain were known as the two main centers for sheep production in the Western world. Spain became very rich because they were the first to breed the fine-wooled merino sheep, which were very important in the wool trade. Money from wool largely paid for Spanish rulers and their trips to the New World by conquistadors.

The powerful Mesta was a group of sheep owners in Spain. It was made up mostly of wealthy merchants, Catholic clergy (church leaders), and nobility (rich families). This group controlled the merino sheep flocks. By the 1600s, the Mesta owned over two million merino sheep.

Mesta flocks moved seasonally across Spain. In spring, they left their winter pastures in Extremadura and Andalusia to graze on summer pastures in Castile, returning in autumn. Spanish rulers wanted to earn more from wool, so they gave the Mesta many legal rights. This often caused problems for local farmers. The huge merino flocks had a legal right to use their migration paths (cañadas). Towns and villages had to let the flocks graze on their common land. The Mesta even had its own sheriffs and courts.

It was also a crime to export merinos without the king's permission. This gave Spain a near-complete control over the breed until the mid-1700s. After the ban was lifted, fine wool sheep began to be sent all over the world. When Louis XVI sent merinos to Rambouillet in 1786, it led to the creation of the modern Rambouillet (or French Merino) breed. After the Napoleonic Wars and the spread of Spanish Merinos worldwide, sheep farming in Spain went back to hardy, coarse-wooled breeds like the Churra. It was no longer as important in the international economy.

The sheep industry in Spain involved large, similar flocks moving across the whole country. In England, the way sheep were managed was different but just as important to the country's economy. Until the early 1900s, owling (smuggling sheep or wool out of the country) was a crime. Even today, the Lord Speaker of the House of Lords sits on a cushion called the Woolsack, which is filled with wool.

In the UK, sheep farming was more focused and settled. This allowed sheep to be bred specifically for their purpose and region. This led to a huge variety of breeds in relation to the country's size. This greater variety also produced different types of wool to compete with Spain's super-fine wool. By the time of Elizabeth I's rule, sheep and wool trade was the main source of tax money for the English Crown. England became a major influence in developing and spreading sheep farming.

An important event for all farm animals was the work of Robert Bakewell in the 1700s. Before him, breeding animals for good traits was often by chance. Bakewell set up the rules for selective breeding (choosing animals with good traits to have babies). He worked with sheep, horses, and cattle. His work later influenced famous scientists like Gregor Mendel and Charles Darwin. His most important contribution to sheep was creating the Leicester Longwool. This breed grew quickly and had a strong body shape. It became the basis for many important modern breeds. Today, the sheep industry in the UK is much smaller. However, special rams (male sheep) can still sell for around 100,000 Pounds sterling at auctions.

Sheep in the Americas

No wild sheep species native to the Americas have ever been tamed, even though they are genetically closer to domestic sheep than many Asian and European species. The first domestic sheep in North America, probably of the Churra breed, arrived with Christopher Columbus's second trip in 1493. The next shipment to cross the Atlantic arrived with Hernán Cortés in 1519, landing in Mexico. No wool or animals are known to have been sent back from these groups. But flocks did spread throughout what is now Mexico and the Southwest United States with Spanish settlers. Churra sheep were also given to the Navajo tribe of Native Americans. They became a key part of their way of life and culture. The Navajo-Churro breed we see today is a result of this history.

North America

The next sheep transport to North America wasn't until 1607, with the ship Susan Constant to Virginia. However, those sheep were all eaten because of a famine. A permanent flock didn't reach the colony until two years later in 1609. In 20 years, the settlers had grown their flock to 400 sheep. By the 1640s, there were about 100,000 sheep in the 13 colonies. In 1662, a wool mill was built in Watertown, Massachusetts. Especially during times of political trouble and civil war in Britain in the 1640s and 1650s, which stopped sea trade, the colonists felt it was important to produce wool for clothing. Many islands off the coast were cleared of predators and used for sheep. Nantucket, Long Island, Martha's Vineyard, and small islands in Boston Harbor are good examples. Some rare American sheep breeds, like the Hog Island sheep, came from these island flocks. Putting semi-wild sheep and goats on islands was a common practice during this time of colonization. Early on, the British government banned sending more sheep to the Americas, or wool from there. This was to stop any threat to the wool trade in the British Isles. This was one of many trade rules that led to the American Revolution. The sheep industry in the Northeast grew despite these bans.

Slowly, starting in the 1800s, sheep production in the U.S. moved westward. Today, most flocks are on Western range lands. During this move, competition between sheep (sometimes called "range maggots" by cattlemen) and cattle farms grew stronger. This sometimes led to range wars. Besides just competing for grazing land and water rights, cattlemen believed that the liquid from sheep's foot glands made cattle not want to graze where sheep had walked. As sheep production focused on the U.S. western ranges, it became linked to other parts of Western culture, like the rodeo. In modern America, a small rodeo event is mutton busting. In this event, children try to stay on a sheep for as long as possible before falling off. Another effect of sheep flocks moving west in North America was the decline of wild species like Bighorn sheep (O. canadensis). Most diseases of domestic sheep can spread to wild sheep. These diseases, along with too much grazing and loss of habitat, are major reasons for the falling numbers of wild sheep. Sheep production in North America reached its highest point in the 1940s and 1950s, with over 55 million sheep. By 2013, the number of sheep in the United States was only 10 percent of what it was in the early 1940s.

In the 1970s, Roy McBride, a farmer from Alpine, Texas, invented a collar filled with a special poison to protect his animals from coyotes, which often attacked their throats. This device is called the livestock protection collar and is widely used in Texas and South Africa.

South America

In South America, especially in Patagonia, there is an active modern sheep industry. Sheep keeping was mostly brought by Spanish and British people who moved to the continent. For them, sheep were a major industry. South America has many sheep, but the country that produces the most (Brazil) had just over 15 million sheep in 2004. This is fewer than most major sheep farming areas. The main challenges for the sheep industry in South America are the huge drop in wool prices in the late 1900s and the loss of land due to logging and too much grazing. The most important region internationally is Patagonia. It was the first to recover from the fall in wool prices. With few predators and almost no competition for grazing (the only large native grazing animal is the guanaco), the region is excellent land for raising sheep. The best production area is around the La Plata river in the Pampas region. Sheep production in Patagonia reached its peak in 1952 with over 21 million sheep, but it has steadily fallen to fewer than ten million today. Most farms focus on producing wool for export from Merino and Corriedale sheep. The economic success of wool flocks has dropped with the fall in prices, while the cattle industry continues to grow.

Sheep in Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand are very important in today's sheep industry. Sheep are a well-known part of both countries' culture and economy. In 1980, New Zealand had the most sheep per person – sheep outnumbered people 12 to 1 (now it's closer to 5 to 1). Australia is definitely the world's largest exporter of sheep (and cattle). In 2007, New Zealand even made February 15 their official National Lamb Day to celebrate their history of sheep production.

The First Fleet brought the first 70 sheep from the Cape of Good Hope to Australia in 1788. The next shipment was 30 sheep from Calcutta and Ireland in 1793. All the early sheep brought to Australia were only used for food for the prison colonies. The start of the Australian wool industry was thanks to Captain John Macarthur. Because Macarthur pushed for it, 16 Spanish merinos were brought in in 1797. This truly began the Australian sheep industry. By 1801, Macarthur had 1,000 sheep. In 1803, he sent 111 kilograms (245 pounds) of wool to England. Today, Macarthur is generally seen as the father of the Australian sheep industry.

The sheep industry in Australia grew incredibly fast. In 1820, the continent had 100,000 sheep. Ten years later, it had one million. By 1840, New South Wales alone had 4 million sheep. Flock numbers grew to 13 million in another decade. Much of this growth in both nations was because Britain actively supported it, wanting wool. However, both countries also worked on their own to develop new breeds that produced a lot of wool. The Corriedale, Coolalee, Coopworth, Perendale, Polwarth, Booroola Merino, Peppin Merino, and Poll Merino were all created in New Zealand or Australia. Wool production was a good industry for colonies far from their home countries. Before fast air and sea shipping, wool was one of the few valuable products that wouldn't spoil on the long journey back to British ports. The large amount of new land and milder winter weather in the region also helped the Australian and New Zealand sheep industries grow.

Flocks in Australia have always been large groups of sheep on fenced land. They are raised to produce medium to super-fine wool for clothing and other products, as well as meat. New Zealand flocks are kept in a similar way to English ones, in fenced areas without shepherds. Wool was once the main source of income for New Zealand sheep owners (especially during the New Zealand wool boom). But today, it has shifted to producing meat for export.

Looking After Sheep: Animal Welfare

The Australian sheep industry has received some international attention regarding certain practices. Groups interested in animal welfare have raised concerns about some methods. For example, a practice called mulesing involves removing skin from a sheep's rear area to help prevent a serious condition called flystrike. While this helps protect the sheep from a painful and often fatal problem, some groups believe it causes unnecessary pain. In response, there are efforts to gradually stop mulesing, and some operations are now done using pain relief. The Animal Welfare Advisory Committee in New Zealand considers mulesing a "special technique" used on some Merino sheep on a small number of farms.

Most of the sheep meat exported from Australia is either frozen carcasses sent to the UK or live export to the Middle East for halal slaughter (a specific way of preparing meat). Some groups have expressed concerns that sheep exported alive to countries outside Australia's animal welfare laws might not be treated humanely. They also point out that halal meat processing facilities exist in Australia, suggesting that live animal export might not always be necessary.

In Spanish: Historia de la oveja doméstica para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la oveja doméstica para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |