Lorenzo Magalotti facts for kids

Lorenzo Magalotti (born October 24, 1637 – died March 2, 1712) was an Italian thinker, writer, diplomat, and poet. He came from a noble family in Rome. His father was in charge of the Pope's mail, and his uncle was a cardinal.

Lorenzo started as a big fan of the famous scientist Galileo Galilei. He became the secretary of a science group called the Accademia del cimento. This group focused on doing experiments and observing nature. However, Lorenzo became unhappy with the arguments between the scientists in the group. He slowly lost interest in science. Instead, he became a traveler and an ambassador for his country. Later in life, he became a poet. He even translated famous English poems like Paradise Lost by John Milton into Italian.

Contents

Life and Early Science

Lorenzo Magalotti studied for seven years, first at the Collegio Romano and then at the University of Pisa. He learned about law and medicine, but then switched to studying mathematics.

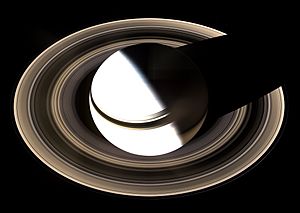

In 1657, the Accademia del Cimento was started by students of Galileo. This group believed in learning through careful observation. They studied the ideas of ancient thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, and also newer scientists like Robert Boyle. The astronomers in the Cimento were the first to confirm Christiaan Huygens's amazing discovery of Saturn's rings.

In 1660, Lorenzo Magalotti became the secretary of the Accademia del Cimento. A few years later, he wrote the only book published by the group, called Saggi di naturali Esperienze (which means "Essays on Natural Experiments"). Many important scientists and thinkers attended the meetings, including Marcello Malpighi (who studied the body), Francesco Redi (who studied tiny living things), and Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (a physicist). They often met at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence.

The members did many experiments. They studied how thermometers and barometers worked, and how air behaved. They also looked into the speed of sound and light, and how things glowed in the dark. They even experimented with magnetism and how water freezes.

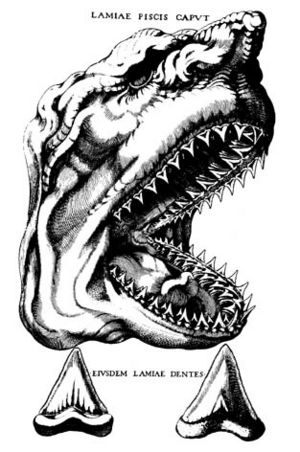

Medicine was a very popular topic back then. A young Danish scientist named Niels Stensen (also known as Steno) came to Florence in 1666. He was an expert in anatomy, which is the study of the body's structure.

Magalotti knew that understanding the comet that appeared in 1664 could help explain the whole Solar System. But instead of trying to explain it scientifically, he joked that the comet's tail was just an optical illusion. Later, when he saw a much better explanation, he admitted he didn't care much about comets. By 1664, he was also helping to decorate the Palazzo Pitti. He made sure to meet all the artists in the city. In 1667, Magalotti visited Ravenna to see the tomb of the famous poet Dante. He also met some English friends, Sir John Finch and Henry Neville, which helped him improve his English. With his childhood friend, Paolo Falconieri, an architect, he planned a trip to Northern Europe.

Travels in the Netherlands

In mid-July, Lorenzo and Paolo left Italy. They crossed the Alps and arrived in Augsburg, Germany, in August. By mid-October, they were in the Hague, Netherlands. There, they visited famous scholars like Isaac Vossius. On November 12, 1667, Magalotti went to Utrecht to see Johann Georg Graevius.

Around the same time, Cosimo III de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, was also on a long trip called a "grand tour." He traveled with a large group of 18 people and 14 carriages, including six cooks! On December 19, they arrived in Amsterdam. On his first day, Cosimo saw the Admiralty of Amsterdam and the huge warehouses of the Dutch East India Company. Cosimo was interested in starting his own East India Company from Livorno, Italy.

Cosimo, who loved art, visited fifteen painters in four months. These included famous Dutch artists like Gerard Dou, Frans van Mieris the Elder, Ludolf Bakhuizen, and Gabriel Metsu. He bought four paintings from Caspar Netscher. Cosimo liked small paintings because they were easier to carry. Around Christmas, he visited some hidden churches and social places, like a madhouse, which was a popular place to visit. He also met with Johannes van Neercassel, a religious leader.

On December 30, 1667, Cosimo went to the Schouwburg of Van Campen, a theater that looked like the Teatro Olimpico in Italy. He probably saw a play called "Medea." Even though they didn't understand the words, it was exciting to watch. On January 12, Cosimo attended a ballet where William III of Orange, who was only 17, performed. Cosimo also met John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen, who had spent a long time in Dutch Brazil.

Many people visited Holland in the 17th century to see art collections. Cosimo visited Gerrit van Uylenburgh, who owned part of a collection by Gerard Reynst. Dutch scientists like Frederik Ruysch and Jan Swammerdam showed them their amazing collections of rare and interesting objects, called "cabinets of curiosities." At Swammerdam's house, who studied insects and knew a lot about bees, Cosimo was with Melchisédech Thévenot.

Cosimo, who was advised by the scientist Niels Stensen, chose not to meet the philosopher Baruch Spinoza. Cosimo bought a painting by Jan van der Heyden. On his last day in Amsterdam, he ordered a self-portrait from the famous painter Rembrandt. He then visited the Plantin House in Antwerp, Belgium, and went to Mechelen and Brussels to order some tapestries. After that, they returned to the Netherlands.

Around Ash-Wednesday, Cosimo traveled to Hamburg, Germany. The journey was difficult because of marshes and mud. Magalotti did not go with him on this part of the trip; he went to London instead.

Travels in England

In London, Magalotti was surprised by how much money the English spent on cock fights. He also saw how much damage was still left from the Great Fire of London. He and his companions were invited to the weekly meetings of the Royal Society, a famous scientific group. They were impressed by a demonstration from Robert Hooke and a warm welcome from the secretary, Henry Oldenburg.

Magalotti was a bit disappointed with his meeting with the King. He and his friends took a seven-day trip to Windsor, Hampton Court, and Oxford, where they visited the famous scientist Robert Boyle. When Magalotti became sick, Boyle visited him every day for hours. Magalotti felt that meeting wise and learned people was worth all the trouble and money spent on traveling. He had met many important scholars and even a king!

They ended their trip in Paris, France, toward the end of April. There, he met Henri Louis Habert de Montmor, who ran a famous science salon, and other important writers and scientists.

Travels to Spain and Portugal

In September, Cosimo went on another trip, this time to Spain. His wife, Marguerite Louise d'Orléans, was often difficult, which might have been a reason for his travels. Magalotti was part of Cosimo's group of 27 men, and his job was to keep a diary of the trip. He also promised to send books to Antonio Magliabechi, a librarian.

From Barcelona, they traveled to Madrid, where they stayed for a month. It is believed that the 8-year-old King Carlos II, who could barely speak or walk, met with Magalotti in a private meeting. Then they visited Córdoba, Seville, and Granada. Magalotti found Spain to be struggling financially and feeling down. He thought its learning was far behind the rest of Europe. He also noted that professors at the University of Alcalá could hardly speak Latin.

By January, he had arrived in Lisbon, Portugal. While Magalotti gave a general overview, another traveler, Filippo Corsini, described Portugal's defenses in detail. Cosimo often stayed in religious buildings and talked with priests. The Monastery of Saint Denis of Odivelas was especially interesting to them. On March 1, Cosimo and his group left Portugal by ship, heading to Galicia, Spain.

More Travels to England and the Netherlands

From La Coruňa, Spain, they sailed for England. After a rough storm, they landed in Kinsale, Ireland, and then went to Plymouth, England. Cosimo spent three months in London, where King Charles II welcomed him. Samuel Pepys, a famous diarist, described Cosimo as "a very jolly and good comely man." Cosimo was also warmly welcomed by the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

When the Grand Duke of Tuscany visited Billingbear House in 1669, Magalotti drew a picture of the house during their two-day stay. This drawing is now in a special book in the Laurentian Library in Florence.

Count Magalotti visited Exeter and wrote that over thirty thousand people in the county of Devon worked in the wool and cloth industries. These goods were sold to places like the West Indies, Spain, France, and Italy. They met the miniature painter Samuel Cooper, who painted Cosimo. Cosimo later asked another artist, John Michael Wright, to paint a portrait of the Duke of Albemarle.

Falconieri presented copies of the new scientific reports from Florence, Saggi di naturali esperienze, to the Royal Society in London and to King Charles II. In England, Magalotti made many good friends, including the famous scientist Isaac Newton. Among the many important people who visited him was Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore, who became his pen pal. Samuel Morland sent him a calculating machine and a loudspeaker. Cosimo became a big fan of England.

On June 14, 1669, they left England and traveled to Rotterdam, Netherlands. Cosimo picked up some paintings he had ordered. He actually saw Rembrandt just a few months before the painter died. Then they visited other Dutch towns like Haarlem, Alkmaar, and Molkwar, a small village built on eight islands connected by 27 bridges. One day, they visited Delft to see some good paintings and met the widow and three daughters of Maarten Tromp, a famous Dutch admiral. They then traveled south through places like Nijmegen and Spa. Cosimo visited King Louis XIV of France and his mother-in-law in Paris. He finally arrived back in Florence on November 1, 1669.

In his travel writings, Magalotti was inspired by other travelers. He didn't want to be like those who just traveled to copy old writings or count steps in bell towers.

Ambassador in Vienna

After 1670, science in Florence changed a bit. Magalotti wasn't sure if many of Cosimo's big plans were worth the huge amounts of money spent. For example, Cosimo wanted to spread Catholicism to England and India, fight the Ottoman Empire, and start trade with Persia. Magalotti continued his travels without the Grand Duke.

In 1673 and 1674, he visited Brussels, Cologne, the Netherlands, Hamburg, Copenhagen, and Stockholm. He was serving as an ambassador for Tuscany at the Imperial court of the Holy Roman Empire in Vienna. In his book Sweden in the year 1674, he described Charles XI of Sweden as "virtually afraid of everything, uneasy to talk to foreigners, and not daring to look anyone in the face." He also noted the king's deep religious devotion. Magalotti said the king's main interests were hunting, the upcoming war, and jokes.

In May 1678, Magalotti returned home. He decided that he was better suited for intellectual work. In 1709, he was chosen to be a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, a great honor.

He passed away in Florence in 1712.

Works

- Historia Electrica

- Philosophia Electrica

- Saggi di naturali esperienze. or Essays on Natural Experiments (1667)

See also

- Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca

Sources

- Acton, Harold: The Last Medici, Macmillan, London, 1980, ISBN: 0-333-29315-0. First published in 1932, first revised edition in 1958.

- Conchrane, E. (1973) Florence in the Forgotten Centuries 1527–1800. A History of Florence and the Florentines in the Age of the Grand Dukes. Book IV Florence in the 1680s. How Lorenzo Magalotti looked in vain for a vocation and finally settled down to sniffing perfumes.

- Hoogewerff, G.J. (1919) De twee reizen van Cosimo de' Medici, prins van Toscane door de Nederlanden. (n.b. including several diaries on the trip in Italian)

- Lorenzo Magalotti at the court of Charles II: his Relazione d'Inghilterra of 1668 / Lorenzo Magalotti ; W.E. Knowles Middleton, editor & translator Lorenzo Magalotti at the Court of Charles II: His Relazione D’Inghilterra of 1668.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |