Luis Walter Alvarez facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Luis Walter Alvarez

|

|

|---|---|

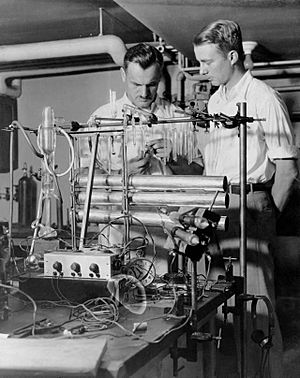

Alvarez with a magnetic monopole detector in 1969

|

|

| Born | June 13, 1911 |

| Died | September 1, 1988 (aged 77) Berkeley, California, U.S.

|

| Education | University of Chicago (BS, MS, PhD) |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Geraldine Smithwick

(m. 1936; div. 1957)Janet L. Landis

(m. 1958) |

| Awards | Collier Trophy (1945) Medal for Merit (1947) John Scott Medal (1953) Albert Einstein Award (1961) National Medal of Science (1963) Pioneer Award (1963) Michelson–Morley Award (1965) Nobel Prize in Physics (1968) Enrico Fermi Award (1987) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley |

| Doctoral advisor | Arthur Compton |

| Signature | |

Luis Walter Alvarez (born June 13, 1911 – died September 1, 1988) was an American experimental physicist, inventor, and professor. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968. He was recognized for finding new types of particles using a special tool called the hydrogen bubble chamber. Many people consider him one of the most brilliant and productive experimental physicists of his time.

After getting his PhD in physics from the University of Chicago in 1936, Alvarez joined Ernest Lawrence at the Radiation Laboratory in California. There, he did experiments to observe a process called K-electron capture in radioactive nuclei. He also created tritium using a machine called a cyclotron and measured how long it lasted. Working with another scientist, Felix Bloch, he measured the magnetic moment of the neutron.

In 1940, Alvarez joined the MIT Radiation Laboratory during World War II. He helped develop many radar systems. These included improvements to Identification friend or foe (IFF) radar beacons, which are now called transponders. He also worked on a system called VIXEN to help planes find enemy submarines without being noticed. The radar system he is most famous for is Ground Controlled Approach (GCA). This system helped planes land safely, even in bad weather, and was very important during the Berlin airlift after the war.

Later, Alvarez worked on the Manhattan project to develop the atomic bomb. He helped design special explosive lenses and new exploding-bridgewire detonators. He watched the first nuclear test, called Trinity, from a B-29 Superfortress plane. He also flew on the B-29 The Great Artiste during the bombing of Hiroshima.

After the war, Alvarez helped design a liquid hydrogen bubble chamber. This allowed his team to take millions of photos of tiny particle interactions. They also created computer systems to study these interactions. This led to the discovery of many new particles, which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1968. He also worked on a project to x-ray the Egyptian pyramids to look for hidden rooms. With his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, he developed the Alvarez hypothesis. This idea suggests that a large asteroid hitting Earth caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Luis Walter Alvarez was born in San Francisco, California, on June 13, 1911. He was the second child of Walter C. Alvarez, a doctor, and Harriet Smyth. His grandfather, Luis F. Álvarez, was a Spanish doctor who found a better way to diagnose macular leprosy. Luis had an older sister, Gladys, and two younger siblings, Bob and Bernice. His aunt, Mabel Alvarez, was a famous California artist.

He went to Madison School in San Francisco and then San Francisco Polytechnic High School. In 1926, his family moved to Rochester, Minnesota, where his father worked at the Mayo Clinic. Luis attended Rochester High School there. He had planned to go to the University of California, Berkeley. However, his teachers encouraged him to attend the University of Chicago instead. He earned his bachelor's degree in 1932, his master's in 1934, and his PhD in 1936 from the University of Chicago.

While studying at Chicago in 1932, he became very interested in physics. He even got to use equipment from the famous physicist Albert A. Michelson. Alvarez also built a special device using Geiger counters to study cosmic rays. With his advisor, Arthur Compton, he did an experiment in Mexico City. They measured the "East–West effect" of cosmic rays. By observing more radiation coming from the west, Alvarez concluded that primary cosmic rays were positively charged.

Early Scientific Work

Luis Alvarez's sister, Gladys, worked for physicist Ernest Lawrence at Berkeley. She told Lawrence about her brother. Lawrence then invited Alvarez to visit an exhibition in Chicago with him. After Alvarez finished his exams in 1936, he asked his sister if Lawrence had any job openings. Soon, he received a job offer from Lawrence. This began his long connection with the University of California, Berkeley. Alvarez married Geraldine Smithwick and they had two children, Walter and Jean. They later divorced, and he married Janet L. Landis in 1958, with whom he had two more children, Donald and Helen.

At the Radiation Laboratory, Alvarez worked with Lawrence's team. He designed experiments to observe K-electron capture in radioactive nuclei. This process had been predicted but never seen before. He used magnets to remove other particles and a special Geiger counter to detect the faint X-rays from K-capture. He published his findings in 1937.

Alvarez also studied what happens when deuterium (a type of hydrogen) particles collide. This fusion reaction creates either tritium (another type of hydrogen) and a proton, or helium-3 and a neutron. At the time, scientists weren't sure if tritium or helium-3 was stable. Based on theories, many thought tritium would be stable and helium-3 unstable. Alvarez proved the opposite. He used the 60-inch cyclotron to accelerate helium-3 nuclei. Since this helium came from deep gas wells where it had been for millions of years, it had to be stable. He then produced radioactive tritium using the cyclotron and measured how long it lasted.

In 1938, Alvarez used his knowledge of the cyclotron to create a special beam of thermal neutrons. He worked with Felix Bloch on a series of experiments. They measured the magnetic moment of the neutron. Their results, published in 1940, were a big step forward in this field.

Contributions During World War II

Radar Development

When British scientists showed American scientists how to use a new device called the cavity magnetron for radar, it changed everything. This led to the creation of the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Alvarez joined this lab in November 1940. He worked on many radar projects. He improved Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) radar beacons, which are now called transponders. He also helped create a system called VIXEN. This system made it harder for enemy submarines to know they had been found by new airborne radars.

Alvarez also invented a special linear dipole antenna. This antenna helped create the Microwave Early Warning system (MEW). It was the first microwave phased-array antenna. He used it in other radar systems too, like the Eagle precision bombing radar. This radar helped planes bomb targets accurately even in bad weather.

The radar system Alvarez is most famous for is Ground Controlled Approach (GCA). This system used Alvarez's special antenna to get very clear images. Ground operators could watch special radar screens and guide landing airplanes to the runway using voice commands. GCA was simple, worked well, and was used by the military for many years after the war. Alvarez received the Collier Trophy in 1945 for his work on GCA.

In 1943, Alvarez spent the summer in England testing GCA. He helped land planes returning from battles in bad weather and trained the British to use the system. There, he met Arthur C. Clarke, who was an RAF radar technician. Clarke later wrote a novel, Glide Path, based on his experiences, with a character inspired by Alvarez. They became long-time friends.

The Manhattan Project

In 1943, Robert Oppenheimer invited Alvarez to work on the Manhattan project at Los Alamos National Laboratory. First, Oppenheimer suggested Alvarez spend a few months with Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago. During this time, Alvarez was asked to figure out how the U.S. could detect if Germany was operating any nuclear reactors. Alvarez suggested using an airplane to detect radioactive gases, like xenon-133, produced by reactors. This equipment flew over Germany but found no radioactive xenon, meaning Germany had not built a working reactor. This was an early idea for using fission products for intelligence gathering.

Alvarez arrived at Los Alamos in 1944. He worked on the design of the "Fat Man" (a plutonium bomb). For this bomb, scientists needed to compress a sphere of plutonium very quickly using explosives. This was a huge technical challenge. To make the explosion perfectly symmetrical, thirty-two explosive charges had to go off at the exact same time. Alvarez directed his student, Lawrence H. Johnston, to use a large capacitor to send a high voltage charge to each explosive lens. This replaced older methods with new exploding-bridgewire detonators. These detonators made all thirty-two charges explode within a tiny fraction of a microsecond. This invention was key to the success of the implosion-type nuclear weapon.

Alvarez's last job for the Manhattan Project was to create special microphones and transmitters. These would be dropped from an aircraft to measure the strength of the blast wave from the atomic explosion. This allowed scientists to calculate the bomb's energy. As a lieutenant colonel in the United States Army, he watched the Trinity nuclear test from a B-29 Superfortress plane.

Flying in the B-29 Superfortress The Great Artiste, alongside the Enola Gay, Alvarez and Johnston measured the blast effect of the "Little Boy" bomb dropped on Hiroshima. A few days later, they used the same equipment to measure the strength of the Nagasaki explosion.

The Bubble Chamber and Nobel Prize

After the war, Alvarez returned to the University of California, Berkeley as a professor. He had many ideas about how to use his wartime radar knowledge to improve particle accelerators. A big idea came from Edwin McMillan with his concept of phase stability, which led to the Bevatron. The Bevatron, built by Lawrence's team, became the world's largest proton accelerator in 1954. It produced many interesting particles, but their interactions were hard to see and study.

Alvarez learned about a new tool called a bubble chamber, invented by Donald Glaser. This device could show the paths of tiny particles. Alvarez realized this was exactly what was needed, especially if it could work with liquid hydrogen. Hydrogen nuclei, which are protons, were the simplest and best targets for interactions with particles from the Bevatron.

He started a project to build a series of bubble chambers. His team built chambers of different sizes, using liquid hydrogen and made of metal with glass windows so the particle paths could be photographed. The chamber could be timed with the accelerator beam, take a picture, and then be ready for the next beam cycle.

This project led to a liquid hydrogen bubble chamber almost 7 feet long. It involved many physicists, students, engineers, and technicians. They took millions of photos of particle interactions and developed computer systems to measure and analyze them. This work led to the discovery of many new particles and resonance states. For this important work, Alvarez received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968.

Scientific Investigations

In 1965, Alvarez suggested using muon tomography to search the Egyptian pyramids for hidden rooms. He planned to use naturally occurring cosmic rays. His idea was to place special detectors, called spark chambers, inside a known room beneath the Pyramid of Khafre. By measuring how many cosmic rays passed through the pyramid in different directions, the detectors could show if there were any empty spaces inside the rock.

Alvarez put together a team of physicists and archaeologists from the United States and Egypt. The equipment was built and the experiment began. It was paused by the 1967 Six-Day War but restarted afterward. The team continued recording and analyzing cosmic rays until 1969. Alvarez reported that no hidden chambers were found in the 19% of the pyramid they surveyed.

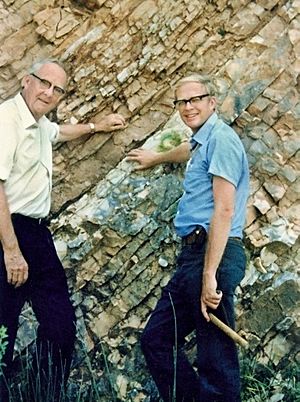

The Dinosaur Extinction Idea

In 1980, Luis Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, along with chemists Frank Asaro and Helen Michel, made a huge discovery about Earth's history.

In the 1970s, Walter Alvarez was doing geology research in Italy. He found a place where limestone layers showed rock from both above and below the time when dinosaurs died out. Exactly at this boundary was a thin layer of clay. Walter told his father that this clay layer marked the time when the dinosaurs and many other living things disappeared, and no one knew why.

Luis Alvarez worked with the nuclear chemists at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. They used a method called neutron activation analysis to study the clay. In 1980, the team published a very important paper. They suggested that an event from space caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. In the years after their paper, the clay was also found to contain soot, tiny glass balls, shocked quartz crystals, microscopic diamonds, and rare minerals. These things form only under extreme heat and pressure.

At first, many geologists criticized their idea. But ten years later, after Alvarez's death, scientists found evidence of a huge impact crater off the coast of Mexico. This discovery strongly supported the idea that an asteroid impact caused the extinction. While other ideas have been suggested, like increased volcanism, the asteroid impact theory is still the most accepted explanation among scientists.

Contributions to Aviation

Alvarez once said that he felt he had two separate careers: one in science and one in aviation. He loved flying and learned to fly in 1933. He later earned ratings to fly with instruments and multi-engine planes. Over 50 years, he flew for more than 1000 hours as the pilot in charge. He found great satisfaction in being responsible for his passengers' lives.

Alvarez made many important contributions to aviation. During World War II, he led the development of several aviation technologies, including the Ground Controlled Approach (GCA) system. He also held the basic patent for the radar transponder.

Later in his career, Alvarez served on many important committees related to civilian and military aviation. These included groups that advised on future air navigation and air traffic control systems. He also helped study how science could improve the United States' ability to fight non-nuclear wars.

His work in aviation led to many adventures. For example, while working on GCA, he became the first civilian to fly a low approach with his view outside the cockpit blocked. He also flew many military aircraft from the co-pilot's seat, including a B-29 Superfortress and a Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. He even survived a plane crash during World War II while he was a passenger.

Death

Luis Alvarez passed away on September 1, 1988. He died from problems after several operations for esophageal cancer. His ashes were scattered over Monterey Bay. His papers are kept at The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.

Awards and Honors

- Fellow of the American Physical Society (1939) and President (1969)

- Collier Trophy of the National Aeronautics Association (1946)

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1947)

- Medal for Merit (1947)

- Fellow of the American Philosophical Society (1953)

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1958)

- California Scientist of the Year (1960)

- Albert Einstein Award (1961)

- Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement (1961)

- National Medal of Science (1963)

- Michelson Award (1965)

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1968)

- Member of the National Academy of Engineering (1969)

- University of Chicago Alumni Medal (1978)

- National Inventors Hall of Fame (1978)

- Enrico Fermi award of the US Department of Energy (1987)

- IEEE Honorary Membership (1988)

- The Boy Scouts of America named their Cub Scout SUPERNOVA award for Alvarez (2012)

- Minor planet 3581 Alvarez is named after him and his son, Walter Alvarez.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Luis Walter Álvarez para niños

In Spanish: Luis Walter Álvarez para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |