Russian Revolution of 1905 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Russian Revolution of 1905 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Demonstrations before Bloody Sunday |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also called the First Russian Revolution, began on January 22, 1905. This was a time of huge political and social trouble across the large Russian Empire. People were mostly upset with the Tsar (the emperor), the rich nobles, and the ruling class.

This unrest included workers going on strike, farmers causing trouble, and soldiers having mutinies (rebelling). Because of this pressure, Tsar Nicholas II had to change his strict ways. He introduced some reforms, which were written in the October Manifesto. These changes led to the creation of the State Duma (a kind of parliament), a system with many political parties, and the Russian Constitution of 1906.

Even though many people took part in the Duma, it couldn't make its own laws. It often disagreed with Nicholas II. The Duma's power was limited, and the Tsar still held most of the control. He could even shut down the Duma, which he did three times to get rid of people who opposed him.

The 1905 revolution started after Russia was defeated in the Russo-Japanese War that same year. This loss made people even more angry. Many parts of society realized that changes were needed. Leaders like Sergei Witte had helped Russia become more industrial. But they didn't do enough to help the people. Tsar Nicholas II and the monarchy barely survived the 1905 Revolution. However, the events of 1905 showed what was coming in the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Many historians believe the 1905 revolution prepared the way for the 1917 Russian Revolutions. In 1917, the monarchy was ended, and the Tsar was executed. Strong calls for big changes were present in 1905. But many revolutionary leaders were either in exile or in prison during this time. The events of 1905 showed how unstable the Tsar's position was. Russia didn't change enough, which directly affected the growing radical politics. Even though radical groups were still a small part of the population, they were gaining strength. Vladimir Lenin, a revolutionary, later called the 1905 Revolution "The Great Dress Rehearsal." He said that without it, the "victory of the October Revolution in 1917 would have been impossible."

Contents

Why the Revolution Started

Many things caused trouble across the Russian Empire in 1905.

Problems for Farmers

Farmers who had recently been freed from serfdom (a system like slavery) didn't earn enough money. They also couldn't sell or mortgage the land they were given. The government wanted farmers to become a stable, land-owning group. They made laws to help them buy land from nobles over many years.

This land was called "allotment land." It wasn't owned by individual farmers but by the whole farming community. Farmers couldn't sell or mortgage this land. This meant they couldn't give up their rights to it. They also had to pay their share of taxes to the village. This plan was supposed to stop farmers from becoming poor city workers. However, the farmers didn't get enough land to live on. Their earnings were often so small that they couldn't buy food or pay their taxes.

The situation got worse as many hungry farmers traveled looking for work. They sometimes walked hundreds of kilometers to find jobs. Desperate farmers sometimes became violent. In 1902, thousands of them in the provinces of Kharkov and Poltava rebelled. They destroyed property and looted noble homes before troops stopped them.

These violent outbreaks made the government pay attention. They created committees to find out why this was happening. The committees found that no part of the countryside was doing well. Some areas, especially the fertile "black-soil region," were getting worse. Even though more land was being farmed, it wasn't enough for the growing farmer population, which had doubled. Everyone agreed that Russia faced a serious farming crisis. This was mainly because too many people lived in rural areas. The investigations showed many problems, but the committees couldn't find solutions that the government liked.

Problems for Different Nationalities

Russia was a huge empire with many different ethnic groups. In the 1800s, Russians saw cultures and religions in a certain order. Non-Russian cultures were allowed, but not always respected. European cultures were preferred over Asian ones. Orthodox Christianity was preferred over other religions.

For a long time, Russian Jews were seen as a special problem. Jews made up only about 4% of the population. But they lived mostly in the western border areas. Like other minorities, Jews lived "miserable and limited lives." They couldn't settle or buy land outside cities. They had limits on attending schools and were mostly kept out of legal jobs. They couldn't vote for city leaders and were not allowed to serve in the Navy or the Guards.

The government's treatment of Jews was similar to how it treated all other national and religious minorities. This policy only made people feel disloyal. There was growing impatience with their lower status and anger against "Russification." Russification meant forcing Russian culture on other groups. The goal was to make a group disappear as a separate part of society.

Besides forcing Russian culture, the government had political reasons for Russification. After the serfs (farmers tied to the land) were freed in 1861, the Russian government had to consider public opinion. But the government failed to get public support. Another reason for Russification was the Polish uprising of 1863. Unlike other minority groups, the Poles were seen as a direct threat to the empire. After the rebellion was crushed, the government tried to reduce Polish cultural influence. In the 1870s, the government started to distrust German people on the western border. They thought Germany might use its power against Russia. The government believed the borders would be safer if the borderlands were more "Russian." All this cultural diversity created a big problem for the Russian government before the revolution.

Problems for Workers

Before the revolution, Russia's economy was in a bad state. The government had tried a "hands-off" approach to business, but it didn't work well until the 1890s. Meanwhile, farming didn't grow, grain prices dropped, and Russia's foreign debt grew. Wars and military spending used up government money. Farmers, who paid taxes, were struggling greatly, leading to a huge famine in 1891.

In the 1890s, Finance Minister Sergei Witte proposed a quick government plan to boost industry. His plan included:

- Lots of government spending on building railroads.

- Support for private businesses.

- High taxes on imported goods to protect Russian industries.

- More exports.

- Making the currency stable.

- Encouraging foreign investments.

His plan worked. In the 1890s, Russian industry grew by 8% each year. Railroads grew by 40% between 1892 and 1902. But this success actually helped cause the 1905 revolution and later the 1917 revolution. It made social problems worse. Industrial growth brought many workers and students to cities, which became centers of political power. It also angered both these new groups and the traditional rural classes. The government's way of paying for industry (by taxing farmers) forced millions of farmers to work in towns. These "peasant workers" saw factory work as a way to help their families back in the village. This helped spread city ideas to the countryside, breaking down the isolation of farmers.

Industrial workers became unhappy with the Tsar's government. This was true even though the government had some laws to protect workers. Some laws said children under 12 couldn't work (except at night in glass factories). Children aged 12 to 15 couldn't work on Sundays or holidays. Workers had to be paid in cash at least once a month. There were limits on fines for workers who were late or made mistakes. Employers couldn't charge workers for lighting in factories.

Despite these laws, workers felt they weren't enough to stop unfair and cruel practices. At the start of the 1900s, Russian factory workers worked about 11 hours a day (10 hours on Saturday). Factory conditions were tough and often unsafe. Attempts to form independent unions were often not allowed. Many workers had to work more than 11 and a half hours a day. Others were still fined too much for being late, making mistakes, or being absent. Russian industrial workers also earned the lowest wages in Europe. Even though living costs were low, an average worker's 16 rubles a month bought much less than a French worker's 110 francs. Also, the same labor laws banned forming trade unions and strikes.

Unhappiness turned into despair for many poor workers. This made them more open to radical ideas. These unhappy, radicalized workers became key to the revolution. They took part in illegal strikes and protests.

The government reacted by arresting labor leaders. They also passed more "fatherly" laws. In 1900, Sergei Zubatov, head of Moscow's security, started "police socialism." This plan allowed workers to form groups with police approval. These groups were supposed to offer healthy activities and self-help. They also aimed to protect workers from ideas that might make them disloyal. Some of these groups formed in Moscow, Odessa, Kyiv, Mykolaiv, and Kharkiv. But these groups and the idea of police socialism failed.

From 1900 to 1903, a time of industrial slowdown, many companies went out of business. This led to fewer jobs. Employees were restless. They would join legal groups but then use them for purposes the groups' sponsors didn't intend. Workers used legal ways to organize strikes or get support for striking workers outside these groups. A strike in 1902 by railroad workers in Vladikavkaz and Rostov-on-Don grew huge. By the next summer, 225,000 workers in various industries in southern Russia and Transcaucasia were on strike. These weren't the first illegal strikes, but their goals and the political awareness among workers and others made them more worrying to the government. The government responded by closing all legal organizations by the end of 1903.

Problems for Educated People

The Minister of the Interior, Plehve, saw schools as a big problem for the government. But he didn't realize it was just a sign of anti-government feelings among educated people. This group included students from universities, other higher schools, and sometimes even high schools and religious schools.

Student radicalism (wanting big changes) began around the time Tsar Alexander II came to power. Alexander ended serfdom and made big changes to Russia's laws and government. These changes were revolutionary for their time. He removed many rules for universities. He also ended required uniforms and military discipline. This brought new freedom to what was taught and read in classes. In turn, this created student groups. Young people were willing to live in poverty to get an education. As universities grew, there was a fast increase in newspapers, journals, and public lectures. The 1860s saw the creation of a new public space in social life and professional groups. This led to the idea that people had a right to their own opinions.

The government was worried by these groups. In 1861, they made rules for getting into universities stricter. They also banned student groups. These rules led to the first student protest ever, held in St. Petersburg. This caused the university to close for two years. The ongoing conflict with the state was a big reason for student protests in the following decades. The mood of the early 1860s led to students getting involved in politics outside universities. This became a key part of student radicalism by the 1870s. Students felt it was their special duty to spread the idea of liberty. They were called to use their freedoms to serve the people.

Over the next two decades, universities produced many of Russia's revolutionaries. Records from the 1860s and 1870s show that more than half of all political crimes were committed by students. This was true even though students were a tiny part of the population. Students on the left-wing were very effective. They felt that neither the universities nor the government could enforce rules. So, radicals simply went ahead with their plans to turn schools into centers of political activity for students and non-students.

They took on problems not related to their studies. They showed defiance and radicalism by:

- Boycotting exams.

- Rioting.

- Organizing marches to support strikers and political prisoners.

- Circulating petitions.

- Writing anti-government propaganda.

This worried the government. But they thought the problem was a lack of training in patriotism and religion. So, they made the school curriculum "tougher." They focused on classical language and mathematics in high schools. But defiance continued. Expulsion, exile, and forced military service also didn't stop students. In fact, when the government finally decided to change the whole education system in 1904, students had become bolder and more resistant than ever.

Growing Opposition

The events of 1905 happened after liberal and academic groups pushed for more democracy and limits on the Tsar's power. There was also an increase in worker strikes for better pay and union recognition. Many socialists saw this as a time when the growing revolutionary movement met with rising efforts to stop change. As Rosa Luxemburg said in 1906, when workers went on strike and faced repression from the government, their demands for economic and political change grew stronger together.

Russian liberals formed groups like the Union of Zemstvo Constitutionalists in 1903 and the Union of Liberation in 1904. These groups wanted a constitutional monarchy (where the ruler's power is limited by a constitution). Russian socialists formed two main groups: the Socialist Revolutionary Party (started in 1902), which followed older Russian populist ideas, and the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (started in 1898).

In late 1904, liberals started holding a series of banquets. These were secretly a way to get around laws against political meetings. The banquets led to calls for political reforms and a constitution. In November 1904, a gathering of local government representatives (zemstvo delegates) called for a constitution, civil liberties, and a parliament. On December 13, 1904, the Moscow City Duma (city council) demanded an elected national legislature, full freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. Other city councils and zemstvo groups made similar demands.

Emperor Nicholas II tried to meet some of these demands. He appointed the liberal Pyotr Dmitrievich Sviatopolk-Mirsky as Minister of the Interior after Vyacheslav von Plehve was killed in July 1904. On December 25, 1904, the Emperor issued a statement. It promised to expand the zemstvo system and give more power to local city councils. It also promised insurance for factory workers, freedom for some minority groups, and an end to censorship. But the most important demand—for a national legislature—was missing.

Worker strikes in the Caucasus began in March 1902. Strikes on the railways, which started over pay, grew to include other issues and spread to other industries. This led to a general strike in Rostov-on-Don in November 1902. Daily meetings of 15,000 to 20,000 people heard openly revolutionary calls for the first time. A massacre ended the strikes. But the reaction to the massacres added political demands to purely economic ones. Luxemburg described the situation in 1903 by saying, "the whole of South Russia in May, June and July was aflame." This included Baku (where wage struggles led to a citywide general strike) and Tiflis, where workers gained shorter working hours. In 1904, huge strike waves happened in Odessa in the spring, in Kyiv in July, and in Baku in December. All this set the stage for the strikes in St. Petersburg in December 1904 to January 1905. These are seen as the first step in the 1905 revolution.

| Years | Average annual strikes |

|---|---|

| 1862–1869 | 6 |

| 1870–1884 | 20 |

| 1885–1894 | 33 |

| 1895–1905 | 176 |

Another factor behind the revolution was the Bloody Sunday massacre of protesters. This happened in January 1905 in St. Petersburg and caused widespread unrest. Lenin urged his Bolshevik followers to take a bigger role. He encouraged violent rebellion. He used slogans about "armed uprising" and "mass terror." This led to accusations that he had moved away from traditional Marxism. He insisted that the Bolsheviks completely separate from the Mensheviks. Many Bolsheviks refused, and both groups attended the Third RSDLP Congress in London in April 1905. Lenin shared his ideas in a pamphlet called Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution. He predicted that Russia's liberal middle class would be happy with a constitutional monarchy and betray the revolution. Instead, he argued that workers and farmers would have to work together to overthrow the Tsar and create a "provisional revolutionary democratic dictatorship."

How the Revolution Began

In December 1904, a strike happened at the Putilov plant (which made railway and artillery parts) in St. Petersburg. Other factories in the city joined in, bringing the number of strikers to 150,000 workers in 382 factories. By January 21, 1905, the city had no electricity, and newspapers stopped being delivered. All public areas were closed.

A controversial Orthodox priest named Georgy Gapon led a huge group of workers. He was in charge of a workers' group supported by the police. They marched to the Winter Palace on Sunday, January 22, 1905. They wanted to give a petition to the Tsar. The troops guarding the Palace were told not to let the demonstrators pass a certain point. At some point, the troops fired on the demonstrators. This caused between 200 and 1,000 deaths. This event became known as Bloody Sunday. Many experts see it as the start of the revolution's active phase.

The events in St. Petersburg made people very angry. This led to a series of huge strikes that quickly spread across the Russian Empire's industrial areas. Polish socialists called for a general strike. By the end of January 1905, over 400,000 workers in Russian Poland were on strike. Half of European Russia's industrial workers went on strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland. There were also strikes in Finland and the Baltic coast. In Riga, 130 protesters were killed on January 26, 1905. In Warsaw, a few days later, over 100 strikers were shot in the streets. By February, there were strikes in the Caucasus, and by April, in the Urals and beyond. In March, all higher schools were closed for the rest of the year. This added radical students to the striking workers.

A strike by railway workers on October 21, 1905, quickly grew into a general strike in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. This led to the creation of the short-lived Saint Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates. This group included both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Leon Trotsky led strike action in over 200 factories. By October 26, 1905, over 2 million workers were on strike. Almost no railways were working in all of Russia. Growing conflicts between ethnic groups in the Caucasus led to Armenian–Tatar massacres. These badly damaged cities and the Baku oilfields.

After the unsuccessful and bloody Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), there was unrest in army reserve units. On January 2, 1905, Port Arthur was lost. In February 1905, the Russian army was defeated at Mukden, losing almost 80,000 men. On May 27–28, 1905, the Russian Baltic Fleet was defeated at Tsushima. Witte was sent to make peace, negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth (signed September 5, 1905). In 1905, there were naval mutinies at Sevastopol (see Sevastopol Uprising), Vladivostok, and Kronstadt. The biggest one was in June with the mutiny aboard the battleship Potemkin. The mutineers eventually gave the battleship to Romanian authorities on July 8 for safety. The Romanians then returned it to Russian authorities the next day. Some sources say over 2,000 sailors died when the mutiny was stopped. The mutinies were disorganized and quickly crushed. Despite these mutinies, the armed forces were mostly loyal, even if unhappy. The government used them widely to control the 1905 unrest.

Nationalist groups were angry about the Russification policy started by Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and Baltic provinces all wanted to govern themselves. They also wanted freedom to use their own languages and promote their own cultures. Muslim groups were also active, forming the Union of the Muslims of Russia in August 1905. Some groups used the chance to fight each other instead of the government. Some nationalists carried out anti-Jewish pogroms (violent attacks), possibly with government help. In total, over 3,000 Jews were killed.

The number of prisoners in the Russian Empire had been very high in 1893 (116,376). But it fell by over a third to a record low of 75,009 in January 1905. This was mainly because the Tsar gave several mass amnesties (pardons).

Height of the Revolution

Tsar Nicholas II agreed on March 2 to create a State Duma of the Russian Empire. But it would only have advisory powers (meaning it could suggest, not make, laws). When its small powers and limits on who could vote were revealed, the unrest grew even more. The Saint Petersburg Soviet was formed. It called for a general strike in October, a refusal to pay taxes, and everyone to take their money out of banks.

In June and July 1905, there were many farmer uprisings. Farmers seized land and tools. Troubles in Russian-controlled Congress Poland reached a peak in June 1905 with the Łódź insurrection. Surprisingly, only one landlord was reported killed. Much more violence happened to farmers outside their communities: 50 deaths were recorded. Anti-Tsarist protests turned into attacks on Jewish communities in the October 1905 Kishinev pogrom.

The October Manifesto, written by Sergei Witte and Alexis Obolenskii, was given to the Tsar on October 14. It closely followed the demands of the Zemstvo Congress in September. It granted basic civil rights, allowed political parties to form, expanded voting rights towards universal suffrage, and made the Duma the main law-making body.

The Tsar waited and argued for three days. But he finally signed the manifesto on October 30, 1905. He said he wanted to avoid a massacre and realized there weren't enough soldiers to do anything else. He regretted signing the document. He said he felt "sick with shame at this betrayal of the dynasty... the betrayal was complete."

When the manifesto was announced, there were spontaneous celebrations in all major cities. Strikes in Saint Petersburg and elsewhere officially ended or quickly stopped. A political amnesty (pardon) was also offered. But these concessions came with renewed, harsh action against the unrest. There was also a backlash from conservative parts of society. Right-wing groups attacked strikers, left-wingers, and Jews.

While Russian liberals were happy with the October Manifesto and got ready for Duma elections, radical socialists and revolutionaries rejected the elections. They called for an armed uprising to destroy the Empire.

Some of the November 1905 uprising in Sevastopol, led by retired naval Lieutenant Pyotr Schmidt, was against the government. Some of it was just general chaos. It included terrorism, worker strikes, farmer unrest, and military mutinies. It was only stopped after a fierce battle. The Trans-Baikal railroad was taken over by striker committees and soldiers returning from Manchuria after the Russo–Japanese War. The Tsar had to send a special group of loyal troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway to restore order.

Between December 5 and 7, there was a general strike by Russian workers. The government sent troops on December 7, and a fierce street-by-street fight began. A week later, the Semyonovsky Regiment was sent in. They used artillery to break up protests and shell workers' areas. On December 18, with about a thousand people dead and parts of the city in ruins, the workers gave up. After a final burst of fighting in Moscow, the uprisings ended in December 1905. By April 1906, more than 14,000 people had been executed and 75,000 imprisoned. One historian says the number of deaths in the 1905 revolution was in the "thousands," with one source putting the figure at over 13,000 deaths.

What Happened Next

After the 1905 Revolution, the Tsar tried to save his rule. He offered reforms, like most rulers do when a revolution pressures them. The military stayed loyal throughout the 1905 Revolution. They shot revolutionaries when the Tsar ordered them to, making it hard to overthrow him. These reforms were outlined in the October Manifesto, which came before the 1906 Constitution. The Manifesto created the Imperial Duma. The Russian Constitution of 1906, also known as the Fundamental Laws, set up a system with many parties and a limited monarchy. The revolutionaries were calmed down and happy with the reforms. But it wasn't enough to stop the 1917 revolution that would later bring down the Tsar's rule.

Creating the Duma and Appointing Stolypin

There had been earlier attempts to create a Russian Duma before the October Manifesto. But these attempts faced strong resistance. One attempt in July 1905, called the Bulygin Duma, tried to make the assembly only an advisory body. It also suggested limiting voting rights to those with more property, excluding factory workers. Neither side—the opposition nor the conservatives—was happy. Another attempt in August 1905 was almost successful. But that also failed when Nicholas insisted the Duma's job be only to advise.

The October Manifesto, besides giving people freedom of speech and assembly, said that no law would be passed without the Imperial Duma's review and approval. The Manifesto also expanded voting rights to almost everyone, allowing more people to take part in the Duma. However, the election law on December 11 still excluded women. Still, the Tsar kept the power to veto (reject) laws.

Ideas for limiting the Duma's law-making powers continued. A decree on February 20, 1906, changed the State Council, which was an advisory group. It became a second chamber with law-making powers "equal to those of the Duma." This change not only went against the Manifesto, but the Council also became a barrier between the Tsar and the Duma. This slowed down any progress the Duma could make. Even three days before the Duma's first meeting, on April 24, 1906, the Fundamental Laws further limited the assembly. They gave the Tsar the sole power to appoint or fire ministers. It seemed like a trap for the Duma. When the assembly met on April 27, it quickly found it couldn't do much without breaking the Fundamental Laws. Defeated and frustrated, most of the assembly voted no confidence and resigned after a few weeks on May 13.

The attacks on the Duma were not just about its law-making powers. By the time the Duma opened, it lacked support from the people. This was largely because the government went back to its strict ways from before the Manifesto. The Soviets (workers' councils) had to hide for a long time. The local councils (zemstvos) turned against the Duma when the issue of taking land came up. The issue of taking land was the most debated of the Duma's proposals. The Duma suggested that the government distribute its treasury, "monastic and imperial lands," and also take private estates. The Duma was actually preparing to upset some of its richer supporters. This decision left the assembly without the political power it needed to be effective.

Nicholas II was still careful about sharing power with officials who wanted reforms. When the 1906 elections swung to the left (more radical), Nicholas immediately ordered the Duma to be dissolved after only 73 days. Hoping to further weaken the assembly, he appointed a tougher prime minister, Petr Stolypin, to replace the liberal Witte. To Nicholas's surprise, Stolypin tried to bring about reforms (like land reform). But he also kept measures that favored the government, like increasing the number of executions of revolutionaries. After the revolution calmed down, he was able to bring economic growth back to Russia's industries. This period lasted until 1914. But Stolypin's efforts did nothing to stop the monarchy from collapsing. They also didn't seem to satisfy the conservatives. Stolypin died from a bullet wound by a revolutionary, Dmitry Bogrov, on September 5, 1911.

The October Manifesto

Even after Bloody Sunday and the defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas II was slow to offer a real solution to the social and political crisis. At this point, he was more worried about his personal life, like his son's illness. His son suffered from haemophilia, and Rasputin was involved in his care. Nicholas also refused to believe that people wanted changes to the absolute rule. He saw "public opinion" as mainly the "intellectuals." He believed he was like a father figure to the Russian people. Sergei Witte, a minister, argued with the Tsar that reforms were needed right away to keep order. It was only after the Revolution gained strength that Nicholas was forced to make changes by writing the October Manifesto.

Issued on October 17, 1905, the Manifesto said the government would give people reforms. These included the right to vote and to meet in assemblies. Its main points were:

- Giving people "personal rights" that could not be taken away. This included freedom of thought, speech, and assembly.

- Allowing people who were previously excluded to take part in the newly formed Duma.

- Making sure no law would be passed without the Imperial Duma's agreement.

This seemed like a time for celebration for Russia's people and reformers. But the Manifesto had problems. Besides not using the word "constitution," one issue was its timing. By October 1905, Nicholas was already dealing with a revolution. Another problem was Nicholas's own thoughts. Witte said in 1911 that the manifesto was written only to relieve pressure on the monarch. He said it was not a "voluntary act." In fact, the writers hoped the Manifesto would cause disagreements among "the enemies of absolute rule" and bring order back to Russia.

One immediate effect it had, for a while, was the start of the Days of Freedom. This was a six-week period from October 17 to early December. During this time, there was an amazing level of freedom for all publications—revolutionary papers, brochures, and so on. This was true even though the Tsar officially kept the power to censor upsetting material. This chance allowed the press to speak to the Tsar and government officials in a harsh, critical way that had never been heard before. Freedom of speech also opened the way for meetings and organized political parties. In Moscow alone, over 400 meetings took place in the first four weeks. Some of the political parties that came from these meetings were the Constitutional Democrats (Kadets), Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, Octobrists, and the far-right Union of the Russian People.

Among all the groups, labor unions benefited most from the Days of Freedom. In fact, this period saw the most union activity in the history of the Russian Empire. At least 67 unions were started in Moscow, and 58 in St. Petersburg. Most of these were formed in November 1905 alone. For the Soviets (workers' councils), it was a very important time. Nearly 50 of the unions in St. Petersburg came under Soviet control. In Moscow, the Soviets had about 80,000 members. This large amount of power allowed the Soviets to form their own militias (armed groups). In St. Petersburg alone, the Soviets claimed about 6,000 armed members. Their purpose was to protect meetings.

Perhaps feeling powerful with their new opportunity, the St. Petersburg Soviets and other socialist parties called for armed struggles against the Tsar's government. This call to war certainly worried the government. Not only were the workers motivated, but the Days of Freedom also had a huge effect on farmers. Seeing an opening in the Tsar's weakening power because of the Manifesto, the farmers, with political organization, protested. In response, the government used its forces to stop and control both the farmers and the workers. Consequences were now in full swing. With a reason in their hands, the government spent December 1905 regaining the power it had lost after Bloody Sunday.

Ironically, the people who wrote the October Manifesto were surprised by the increase in revolts. One of the main reasons for writing the October Manifesto was the government's "fear of the revolutionary movement." In fact, many officials believed this fear was almost the only reason the Manifesto was created. Among those most scared was Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov, governor general of St. Petersburg. Trepov urged Nicholas II to stick to the principles in the Manifesto. He said that "every retreat... would be dangerous to the dynasty."

Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 was published just before the First Duma met. The new Fundamental Law was created to put the promises of the October Manifesto into action and add new reforms. The Tsar was confirmed as the absolute leader. He had complete control of the government, foreign policy, the church, and the armed forces. The Duma's structure was changed. It became a lower chamber below the Council of Ministers. Half of its members were elected, and half were appointed by the Tsar. Laws had to be approved by the Duma, the council, and the Tsar to become law. The Fundamental State Laws were the "peak of all the events that started in October 1905." They made the new situation permanent. The Russian Constitution of 1906 was not just about putting the October Manifesto into place. The constitution's introduction stated (and emphasized) the following:

- The Russian State is one and cannot be divided.

- The Grand Duchy of Finland, while a part of the Russian State, is managed internally by special rules based on special laws.

- The Russian language is the common language of the state. Its use is required in the army, navy, and all state and public institutions. The use of local languages in state and public institutions is decided by special laws.

The Constitution did not mention any of the promises of the October Manifesto. While it did put the earlier promises into law, its only purpose seemed to be to promote the monarchy and not go back on previous promises. The new rules and the new constitutional monarchy did not satisfy Russians or Lenin. The Constitution lasted until the empire fell in 1917.

Repression and Punishment

The years of revolution saw a big increase in death sentences and executions.

| Year | Number of executions by different accounts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report by Ministry of Internal Affairs Police Department to the State Duma on February 19, 1909 | Report by Ministry of War Military Justice department | By Oscar Gruzenberg | Report by Mikhail Borovitinov, assistant head of Ministry of Justice Chief Prison Administration, at the International Prison Congress in Washington, 1910. | |

| 1905 | 10 | 19 | 26 | 20 |

| 1906 | 144 | 236 | 225 | 144 |

| 1907 | 456 | 627 | 624 | 1,139 |

| 1908 | 825 | 1,330 | 1,349 | 825 |

| Total | 1,435 + 683 = 2,118 | 2,212 | 2,235 | 2,628 |

| Year | Number of executions |

|---|---|

| 1909 | 537 |

| 1910 | 129 |

| 1911 | 352 |

| 1912 | 123 |

| 1913 | 25 |

These numbers only show executions of civilians. They do not include many quick executions by army groups or executions of rebelling soldiers. Peter Kropotkin, an anarchist, noted that official numbers did not include executions during special military actions, especially in Siberia, Caucasus, and the Baltic provinces. By 1906, about 4,509 political prisoners were held in Russian Poland. This was 20 percent of all prisoners in the empire.

Revolution in Other Regions

Ivanovo Soviet

Ivanovo Voznesensk was known as the 'Russian Manchester' because of its textile factories. In 1905, the local revolutionaries there were mostly Bolsheviks. It was the first Bolshevik group where workers outnumbered intellectuals.

- May 11, 1905: The 'Group', the revolutionary leaders, called for all textile mill workers to strike.

- May 12: The strike began. Strike leaders met in the local woods.

- May 13: 40,000 workers gathered before the Administration Building. They gave Svirskii, the regional factory inspector, a list of demands.

- May 14: Workers elected delegates. Svirskii had suggested this, as he wanted people to negotiate with. A large meeting was held in Administration Square. Svirskii told them the mill owners would not meet their demands. But they would negotiate with elected mill delegates, who would be safe from being arrested, according to the governor.

- May 15: Svirskii told the strikers they could only negotiate about each factory one by one. But they could hold elections anywhere. The strikers elected delegates to represent each mill while they were still in the streets. Later, the delegates elected a chairman.

- May 17: The meetings were moved to the bank of the Talka River, as suggested by the police chief.

- May 27: The delegates' meeting house was closed.

- June 3: Cossacks (a type of soldier) broke up a workers' meeting, arresting over 20 men. Workers started cutting telephone wires and burned down a mill.

- June 9: The police chief resigned.

- June 12: All prisoners were released. Most mill owners fled to Moscow. Neither side gave in.

- June 27: Workers agreed to stop striking on July 1.

Poland

The 1905–1907 revolution was the biggest wave of strikes and freedom movements Poland had ever seen. It remained so until the 1970s and 1980s. In 1905, 93.2% of Congress Poland's industrial workers went on strike. The first part of the revolution was mostly huge strikes, rallies, and protests. Later, this turned into street fights with police and the army. There were also bomb attacks and robberies of money transports going to Russian financial places.

One of the major events was the uprising in Łódź in June 1905. But unrest happened in many other areas too. Warsaw was also a busy center of resistance, especially with strikes. Further south, the Republika Ostrowiecka and Republika Zagłębiowska were declared (Russian control was later restored in these areas when strict military rule was put in place). Until November 1905, Poland was at the front of the revolutionary movement in the Russian Empire. This was true even with many soldiers sent against it. Even when the unrest started to die down, larger strikes happened more often in Poland than in other parts of the Empire in 1906–1907.

Because of its size, violence, radical ideas, and effects, some Polish historians even see the events of the 1905 revolution in Poland as a fourth Polish uprising against the Russian Empire. Rosa Luxemburg described Poland as "one of the most explosive centers of the revolutionary movement." She said that in 1905, Poland "marched at the head of the Russian Revolution."

Finland

In the Grand Duchy of Finland, the Social Democrats organized the general strike of 1905 (November 12–19). The Red Guards were formed, led by captain Johan Kock. During the general strike, the Red Declaration was published in Tampere. It was written by Finnish politician and journalist Yrjö Mäkelin. It demanded the end of the Senate of Finland, the right for everyone to vote, political freedoms, and an end to censorship. Leo Mechelin, a leader of those who wanted a constitution, wrote the November Manifesto. The revolution led to the end of the Diet of Finland and the old system of four social classes. It also led to the creation of the modern Parliament of Finland. It also temporarily stopped the Russification policy that Russia had started in 1899.

On August 12, 1906, Russian artillerymen and military engineers rebelled in the fortress of Sveaborg (later called Suomenlinna), Helsinki. The Finnish Red Guards supported the Sveaborg Rebellion with a general strike. But the mutiny was stopped within 60 hours by loyal troops and ships of the Baltic Fleet.

Estonia

In the Governorate of Estonia, Estonians called for freedom of the press and assembly. They also wanted the right for everyone to vote and to govern themselves. On October 29, the Russian army opened fire on a meeting in a street market in Tallinn. About 8,000–10,000 people were there. 94 people were killed, and over 200 were injured. The October Manifesto was supported in Estonia. The Estonian flag was shown publicly for the first time. Jaan Tõnisson used the new political freedoms to expand the rights of Estonians. He started the first Estonian political party – the National Progress Party.

Another, more radical political group, the Estonian Social Democratic Workers' Union, was also founded. The moderate supporters of Tõnisson and the more radical supporters of Jaan Teemant couldn't agree on how to continue the revolution. They only agreed that both wanted to limit the rights of Baltic Germans and end Russification. The radical views were publicly welcomed. In December 1905, strict military rule was declared in Tallinn. A total of 160 manor houses were looted. This resulted in about 400 workers and farmers being killed by the army. Estonian gains from the revolution were small. But the uneasy peace between 1905 and 1917 allowed Estonians to work towards becoming their own nation.

Latvia

After demonstrators were shot in St. Petersburg, a large general strike began in Riga. On January 26, Russian army troops opened fire on demonstrators. They killed 73 and injured 200 people. In the middle of 1905, the revolutionary events moved to the countryside. There were mass meetings and protests. 470 new local government bodies were elected in 94% of the parishes in Latvia. The Congress of Parish Representatives was held in Riga in November. In autumn 1905, armed conflict began between the Baltic German nobles and Latvian farmers in the rural areas of Livonia and Courland. In Courland, the farmers took over or surrounded several towns. In Livonia, the fighters controlled the Rūjiena-Pärnu railway line. Strict military rule was declared in Courland in August 1905, and in Livonia in late November. Special groups were sent in mid-December to stop the movement. They executed 1170 people without trial or investigation. They also burned 300 farmer homes. Thousands were sent away to Siberia. Many Latvian intellectuals only escaped by fleeing to Western Europe or the US. In 1906, the revolutionary movement slowly died down.

Cultural Impact

The 1905 Revolution inspired many artists and writers:

- Artists Valentin Serov, Boris Kustodiev, Ivan Bilibin, and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky published their works about the 1905 Revolution in the funny magazine Zhupel.

- Novels like Mother (1907) by Maxim Gorky and The Silver Dove (1909) by Andrei Bely were written because of the 1905 Revolution.

- Battleship Potemkin (1925), a film by Sergei Eisenstein, was originally meant to be a pro-Bolshevik story of the 1905 Russian Revolution.

- Doctor Zhivago, a 1957 novel by Boris Pasternak, takes place from 1902 to World War II.

- Symphony No. 11 (Shostakovich), called The Year 1905, was written in 1957.

See also

In Spanish: Revolución rusa de 1905 para niños

In Spanish: Revolución rusa de 1905 para niños

- Łódź insurrection (1905)

- Russian Revolution of 1917

Images for kids

-

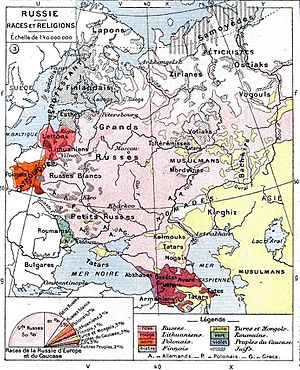

French ethnic map of European Russia from 1898. In accordance with official "All-Russian" ideology of the time, the group labelled "Russians" includes not only what are considered Russians today (here called "Great Russians"), but also Belarusians ("White Russians") and Ukrainians ("Little Russians").

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |