19th-century London facts for kids

In the 1800s, London grew into a huge and very important global city. It became the biggest city in the world around 1825. It was also the world's largest port and a major center for money and trade. During this time, railways were built to connect London to the rest of Britain. The London Underground (the Tube) was also created. New roads, a modern sewer system, and many famous landmarks were also built.

Contents

London's Big Growth in the 1800s

During the 19th century, London became the world's largest city. It was also the capital of the British Empire. Its population grew from over 1 million people in 1801 to more than 5.5 million by 1891. By the 1860s, London was much larger than other big cities like Beijing and Paris. It was even five times bigger than New York City.

At the start of the 1800s, London's main part was smaller. It was bordered by Park Lane and Hyde Park to the west. To the north, it reached Marylebone Road. It also stretched along the River Thames at Southwark and east to Bethnal Green. As the population grew, London's size expanded greatly. It covered 122 square miles in 1851 and grew to 693 square miles by 1896.

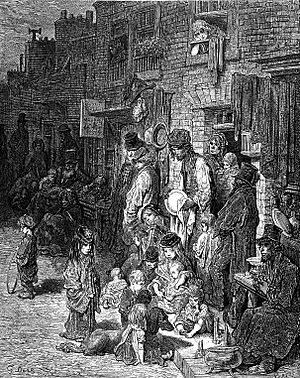

London became a global hub for politics, money, and trade. While the city became very rich, many people lived in poverty. Millions lived in crowded and unhealthy slums. Famous author Charles Dickens wrote about the lives of the poor in books like Oliver Twist.

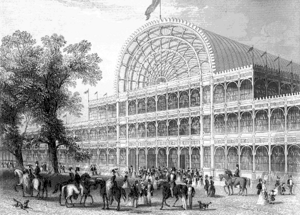

A very famous event in 19th-century London was the Great Exhibition of 1851. This big fair was held at The Crystal Palace. It attracted visitors from all over the world. It showed Britain's power at the height of its empire.

Who Moved to London?

As the capital of a huge empire, London attracted many people. Immigrants came from the colonies and poorer parts of Europe. A large number of Irish people moved to the city during the Victorian era. Many were escaping the terrible Great Famine (1845–1849). At one point, Irish immigrants made up about 20% of London's population. In 1853, about 200,000 Irish people lived in London. This was a huge number, almost as big as three other major Irish cities combined.

London also became home to a large Jewish community. By 1882, there were about 46,000 Jewish people. There was also a small Indian population, mostly sailors. In the 1880s and 1890s, many thousands of Jewish people came to London. They were escaping hardship in Eastern Europe. They often settled in the East End, in areas like Whitechapel. Many worked in clothing workshops and markets, especially around Petticoat Lane Market. As some Jewish families became more successful, they moved to nearby suburbs like Hackney.

An Italian community formed in Soho and Clerkenwell. By 1900, about 11,500 Italians lived in London. Most were young men. They often worked as organ grinders or sold street food like ice cream.

After the Strangers' Home for Asiatics, Africans and South Sea Islanders opened in 1856, a small group of Chinese sailors settled in Limehouse. They opened shops and boarding houses for other Chinese sailors. This area became London's first Chinatown. Writers like Charles Dickens sometimes described it in their novels.

London's Economy

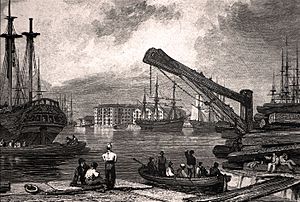

London's Busy Port

London was the world's largest port throughout the 19th century. It was also a major shipbuilding center. At the start of the century, the Pool of London was too crowded for all the ships. Sailors sometimes waited a week to unload goods. This led to theft and avoided taxes. To stop this, a private police force was set up in 1798. This Marine Police Force was very successful. In 1800, it became a public force. Later, in 1839, it joined the Metropolitan Police.

To handle more trade, new docks were built. The first major one was the West India Docks in 1802. These docks were very secure and had huge warehouses. They could hold nearly a million tons of goods. The new docks helped London keep its place as a top port.

The Commercial Road was built in 1803 to connect the docks to the city. In 1812, the Regent's Canal was extended to Limehouse. This canal linked the docks to industrial cities in The Midlands. It helped transport goods like coal and timber around London. Many industries, especially gasworks, grew along the canal.

Soon, other docks were built, like the East India Docks and the London Docks. The St Katharine Docks opened in 1828. In Rotherhithe, the Surrey Commercial Docks Company grew. This area specialized in trade from the Baltic and North America. It was known for its large timber ponds.

As steamships became popular, older docks were too shallow. So, new, deeper docks were built further east. These included the Royal Victoria Dock (1855) and the Royal Albert Dock (1880). The Royal Albert Dock was the largest in the world. It was the first to have electric lights and hydraulic cranes. By 1880, the Port of London handled 8 million tons of goods a year. This was a huge increase from 800,000 tons in 1800.

Many people worked at the docks. Their jobs were often low-paid and unstable. This led to the London Dock Strike of 1889. About 130,000 workers went on strike. The strike stopped port activity. The dock owners eventually agreed to better pay and working conditions.

Shipbuilding in London

In the first half of the 19th century, London's shipbuilding industry was very advanced. It built some of the best ships in the world. Firms like Wigram and Green built fast sailing ships. London shipyards supplied most of the Navy's warships. The Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company built the amazing HMS Warrior in 1860. It was the world's first iron-hulled, armor-plated warship. This company also worked on big projects like Blackfriars Railway Bridge.

London engineering companies like Maudslay, Sons and Field made steam engines for ships. This helped ships switch from sails to steam power. In 1838, the world's first screw-propelled steamer, SS Archimedes, was launched. This new technology was much better than paddle steamers. The largest ship of its time, the SS Great Eastern, was built in London in 1858. It was the biggest ship in the world until 1901.

However, by the late 1800s, London's shipbuilding declined. Newer shipyards in Scotland and northern England could build larger ships more cheaply. The old Royal Dockyards at Woolwich and Deptford closed in 1869. They were too far upriver and too shallow for modern ships.

London's Financial Power

The City of London became much more important as a financial center. After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, a lot of money was invested. London was strong in banking, stock trading, and shipping insurance. It was also home to most of Britain's shipping and trading companies. As the Industrial Revolution grew, there was a huge demand for money to invest in railways, shipping, and factories.

British money also flowed overseas. About £100 million was invested abroad between 1815 and 1830. By 1854, this grew to £550 million. By the end of the century, British foreign investment was nearly £2.4 billion. In 1862, London had 83 banks and hundreds of stockbroking firms. The Bank of England was at the heart of this. By the end of the century, it held £20 million in gold. It printed 15,000 new banknotes every day.

Even though many people moved out of the City of London to the suburbs, it remained the center of English business. The number of people working in the City grew from 200,000 in 1871 to 364,000 by 1911.

London's Homes and Living Conditions

Housing Growth

London grew a lot in the 19th century because new homes were built. These homes were needed for the fast-growing population. New Transport in London helped suburbs grow outwards. People wanted to live away from the busy city center. Suburbs varied greatly, from very rich areas to places for the lower-middle classes. Many types of homes were built, including terraced, semi-detached, and detached houses.

Suburbs were seen as a step up for many families. However, they were sometimes made fun of in magazines like Punch. While older Georgian terraced houses were once grand, by the late 1800s, simpler ones were built for working-class families. Many of London's inner city areas still have these terraced houses today.

Poverty in London

Next to the rich areas of the City of London, there were many very poor Londoners. Author George W. M. Reynolds wrote in 1844 about the huge difference between rich and poor. He said that the city had churches, but also places where the poor went to forget their troubles. There were pawn shops where people sold their clothes for food. Prisons held those driven to crime by hunger. Workhouses were places where the poor went to die.

One of the most famous slum areas was St. Giles. It was known for its crowded homes and hidden alleys. Lord Byron spoke in Parliament in 1812 about the terrible poverty he saw there. The worst part of St. Giles was "The Rookery." In 1852, one street there had over 1,100 people living in crowded, dirty buildings. Poverty got worse when many poor Irish immigrants arrived during the Great Famine of 1848.

Starting in the 1830s, the government began to clear out slums like St. Giles. New Oxford Street was built through "The Rookery" in 1847. This removed the worst parts. However, many evicted people just moved to nearby streets, making them even more crowded.

In the mid-1800s, people like Octavia Hill and groups like the Peabody Trust worked to build good, affordable homes for working-class people. The Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was given power to clear slums and set rules for landlords. In 1890, a new law allowed the London County Council (LCC) to build its own housing. This started a program to build social housing in areas like Bethnal Green.

The East End's Challenges

The East End of London was always an area for working-class people. It was near the docks and polluting industries. By the late 1800s, it gained a bad reputation for crime and extreme poverty. In 1881, over 1 million people lived in the East End. A third of them lived in poverty. The Cheap Trains Act 1883 helped some working-class people move out. But it left the poorest people behind in the East End.

American author Jack London visited the East End in 1903. He wrote that many Londoners had never been there. He described it as "one unending slum." He saw streets filled with people who looked tired or unhealthy. He wrote about "miles of bricks and squalor."

The East End's reputation was very low by 1903. The 1888 Whitechapel murders (by Jack the Ripper) brought international attention to its poor conditions. Books like George Gissing's The Nether World showed grim pictures of London's poor areas. The most important work on London poverty was Charles Booth's Life and Labour of the People in London. This 17-volume work, published between 1889 and 1903, mapped out poverty levels across the city.

Health and Sickness

The very crowded conditions in areas like the East End led to unhealthy living. This caused many diseases. The child death rate in the East End was 20%. The average life expectancy for a worker there was only 19 years. In Bethnal Green, a poor area, 1 in 41 people died in 1847. This rate stayed almost the same until 1893. In rich areas like Kensington, the death rate was much lower. London's overall life expectancy in the mid-1800s was just 37 years.

The most serious diseases were tuberculosis, cholera (until the 1860s), rickets, scarlet fever, and typhoid. Smallpox was also a feared disease. There were smallpox outbreaks in 1816–19, 1825–26, 1837–40, 1871, and 1881. At first, there were only a few hospitals for smallpox. This changed when the Metropolitan Asylums Board was created in 1867. It began building new hospitals. When the 1881 epidemic hit, the hospitals were overwhelmed. Old ships were used as hospital ships. These floating hospitals helped treat many patients. They eventually led to permanent isolation hospitals being built, which helped end smallpox epidemics.

Getting Around London

As London grew, public transport became very important. The first horse-drawn omnibuses started in 1829. By 1854, there were 3,000 of them. Each carried about 300 passengers a day. The two-wheeled hansom cab was the most common type of taxi. By the end of the century, there were about 10,000 cabs in London.

From the 1870s, London also had a growing tram network. Trams provided local transport in the suburbs. The first horse-drawn tramways were installed in 1860. They were popular with passengers. However, their raised rails made traffic difficult for other vehicles. Trams were later reintroduced after the Tramways Act 1870. By 1893, there were about 1,000 tram cars on 135 miles of track.

The Arrival of Railways

Railways changed London a lot in the 19th century. A new network of railways allowed suburbs to grow. Middle-class and wealthy people could live outside the city and travel to work. This led to London's huge outward growth. But it also made the class divide worse. Richer people moved to the suburbs, leaving the poor in the inner city. New railway lines were often built through working-class areas. This was because land was cheaper there.

The first railway in London opened in 1836. It was a short line from London Bridge to Greenwich. Soon, large train stations were built. These connected London to every part of Britain. They included Euston (1837) and Paddington (1838). By 1865, there were 12 main railway stations. The Cheap Trains Act 1883 helped poorer Londoners move. It made train fares cheaper. This led to new working-class suburbs like West Ham.

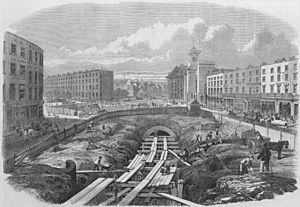

London's Underground System

Traffic on London's roads became very bad. So, people suggested building underground railways. The Thames Tunnel (1843) showed that such engineering was possible. In 1860, Parliament approved London's first underground railway. This was the Metropolitan Railway. It opened in 1863 and was the world's oldest mass transit system. It was built by digging a trench, building brick tunnels, and then covering it up. The Metropolitan ran from Farringdon to Paddington. It used steam locomotives and gas lamps. It was a huge success, carrying 9.5 million passengers in its first year.

More underground lines were built after the Metropolitan's success. The Metropolitan District Line opened in 1865. The first true "tube" line was the City and South London Railway, opened in 1890. It was dug deep underground using a special shield. It was London's first underground line with electric trains. This meant tunnels could be dug deeper because no smoke or steam ventilation was needed. By 1894, over 228 million passengers used the underground railways. Before 1900, another deep-level tube, the Waterloo & City Line, opened. It connected the City of London to Waterloo station.

London's Infrastructure

New Roads

Many new roads were built after the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was formed in 1855. These included the Embankment (from 1864) and Charing Cross Road (from 1877). The MBW aimed to improve travel between important areas like Charing Cross and Piccadilly Circus. This meant tearing down many homes in slums like Soho and St. Giles. The MBW had to rehouse over 3,000 workers.

One of the biggest road projects was Regent Street. The Prince Regent wanted a grand road. It would link his home to Regent's Park. This new road cleared narrow streets and eased traffic. It also allowed new homes to be built around Regent's Park. Regent Street was designed by John Nash. It opened around 1819. It became a busy shopping area.

In 1890, London had 5,728 street accidents, with 144 deaths. London was the site of the world's first traffic light. It was installed in 1868 near the Houses of Parliament. It was a 20-foot column with a gas lamp on top.

Amazing Engineering Projects

The 19th century saw amazing engineering in London. The Thames Tunnel opened in 1843. It was called the "Eighth Wonder of the World." Designed by Marc Isambard Brunel, it was the first tunnel built successfully under a river. It took 18 difficult years to build. Workers faced floods and gas leaks. It was meant for goods but became a pedestrian tunnel at first. In 1865, it was bought by the East London Railway for trains.

The Thames Embankment was another huge project. It changed the riverside between Chelsea and Blackfriars. There were three sections built between 1864 and 1874. The embankments protected low areas from flooding. They also created new land for building.

The Victoria Embankment was the biggest part. It hid a massive sewer tunnel. This tunnel carried waste away from the River Thames. It also allowed an extension of the Metropolitan District Line underground. The Victoria Embankment created over 37 acres of new land. It also provided a wide road and public gardens.

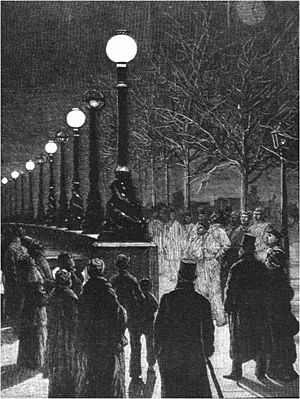

All three sections of the Embankment were built with grey granite. They had beautiful cast iron lamps and London plane trees. In 1878, the Victoria Embankment's lamps became electric. This made it the first street in Britain to be lit by electricity.

New Bridges

Many new bridges were built over the Thames in the 19th century. These improved travel to Southwark. In 1800, only three bridges connected Westminster to the south bank. These were Westminster Bridge, Blackfriars Bridge, and the old London Bridge. These old bridges were falling apart. Old London Bridge, built in the 1200s, was too narrow and blocked the river flow.

"New" London Bridge was built from 1824 to 1831. It was much wider. New Westminster Bridge opened in 1862. Blackfriars Bridge was also rebuilt starting in 1864.

Several new bridges for roads, pedestrians, and railways were also built. These included Southwark Bridge (1819) and Waterloo Bridge (1817). Tower Bridge (1894) was a major addition. Further upriver, new bridges included Lambeth Bridge (1862) and Vauxhall Bridge (1816).

The need for new bridges came from London's huge population growth. London Bridge was the busiest route. In 1882, it had over 22,000 vehicles and 110,000 pedestrians crossing daily. This led to the building of Tower Bridge. It was designed by Sir Horace Jones. It was a bascule bridge, meaning its middle section could be raised. This allowed tall ships to pass through. It was an amazing engineering feat.

Lighting Up London

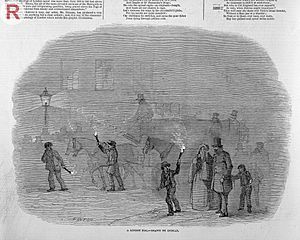

Gas lighting changed London in the early 1800s. For the first time, streets were well lit. Before this, oil lamps were used, but only in the darkest months. The first gaslight in London was at the Lyceum Theatre in 1804. In 1805, gaslights were installed along Pall Mall. The Westminster Gas Light and Coke Company was formed in 1810. By 1813, Westminster Bridge was lit by gas. Gaslight helped shops stay open later. It also made streets safer.

By 1823, London had about 40,000 gas street lamps. By 1880, there were one million. London became known for its bright streets at night. The Metropolitan Gas Act 1860 gave gas companies monopolies in certain areas. This led to higher prices. Later laws helped lower prices and improve service. By the late 1870s, there were only 6 gas companies left.

Electric lighting slowly appeared in the late 1800s. It was expensive at first. In 1879, electric arc lamps were tested on the Victoria Embankment. They were judged better than gas. The same year, Siemens installed electric lights at the Royal Albert Hall. The world's first coal-fueled power station for public use opened in 1882. This was the Edison Electric Light Station at Holborn Viaduct. It powered 968 Edison light bulbs.

London's Culture

Museums and Learning

Many of London's major museums were built or founded in the 19th century. These include the British Museum (built 1823–1852) and The National Gallery (built 1832–8). The National Portrait Gallery was founded in 1856. The Tate Britain opened in 1897.

The British Museum had been around since 1753. But it needed a major expansion for the huge collection of books from King George III. The current building, with its grand Greek-style front, was built gradually until 1857. The Round Reading Room had the second largest dome in the world when it was finished. By 1878, it held 1.5 million books.

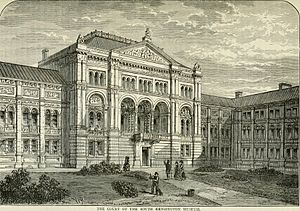

The large group of museums at South Kensington began after the Great Exhibition of 1851. Profits from the Exhibition were used to buy land. The idea was to create a center for culture, science, and education. The first museum there was the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum). It opened in 1856. In 1899, Queen Victoria renamed it the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The land also hosted the 1862 International Exhibition. Later, it became home to the Natural History and Science Museums. The Natural History Museum building was built between 1873 and 1884. By the end of the century, these museums were joined by the Royal Albert Hall (1871) and the Royal College of Music (1894).

Theatre and Entertainment

Besides museums, popular entertainment grew across the city. At the start of the century, London had only three main theaters. Old laws limited where plays could be performed. But these rules slowly changed. In 1843, a new law allowed all licensed theaters to put on plays. This helped theater become more popular. By 1851, there were 19 theaters. By 1899, London had 61 theaters, with 38 in the West End.

Music halls also became popular. These were places where people could eat, drink, and watch live performances. The Canterbury Music Hall opened in 1852. It was the first building made just for music hall shows. It had a large hall with tables for dining. By 1875, there were 375 music halls in London. Many were in the East End. Music halls became a big part of cockney culture. Famous performers like George Robey entertained crowds with songs and comedy.

London's Government and Public Services

In 1829, Home Secretary Robert Peel created the Metropolitan Police. This was a police force for most of London. The City of London had its own police force. The Met absorbed older forces like the Bow Street Runners. Police officers were nicknamed "bobbies" or "peelers" after Robert Peel.

London's urban area grew very fast. This led to a need for better local government. Outside the City of London, local government was a mess. There were many small, uncoordinated groups. For example, drainage was handled by seven different groups. In 1855, the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was created. It was London's first city-wide government body. It aimed to build better infrastructure.

The MBW was not directly elected, so people didn't like it much. In 1888, it was replaced by the London County Council (LCC). This was the first elected body to govern all of London. In 1900, London was divided into 28 metropolitan boroughs. These provided more local administration.

Parliament also focused on public health. In 1867, the Metropolitan Poor Act created the Metropolitan Asylums Board. It aimed to move healthcare for the poor away from workhouses. New hospitals were planned.

Improving Sanitation

One of the MBW's first jobs was to fix London's sanitation. Sewers were not widespread. Most human waste went into cesspools, which often overflowed. An 1847 rule made all waste go into sewers. But this meant the Thames, London's drinking water source, became very polluted. This led to repeated cholera outbreaks in 1832, 1849, 1854, and 1866. It also caused The Great Stink of 1858.

After the Great Stink, Parliament approved a huge sewer system. Joseph Bazalgette was the engineer in charge. He built over 1300 miles of tunnels and pipes. This system took sewage away from London and provided clean water. When it was finished, deaths from disease dropped a lot. Bazalgette's system is still used today.

Even with better sewers, street sanitation was a problem. By the 1890s, London had about 300,000 horses. They dropped 1,000 tons of waste on the streets every day. Boys were hired to collect horse waste. This continued until cars replaced horses.

Social reformer Edwin Chadwick criticized waste removal in his 1842 report. He said rotting food and waste on the streets caused disease. He pushed for better water supplies and drains. This led to the Public Health Act 1848. It made local councils responsible for street cleaning and sewers. More powerful laws were passed in 1872 and 1875. These laws made councils provide proper drainage and required new homes to have running water.

London's Pollution Problems

The Notorious Fog

Burning cheap coal caused London's famous "pea soup fog." Air pollution from burning wood or coal had always been a problem. But in the 19th century, with more people and industries, the fogs became much worse and more deadly.

The fogs were worst in November. They often happened throughout autumn and winter. Smoke and soot from chimneys mixed with natural mist. This created a thick, greasy, and smelly fog. It could be green-yellow, brown, black, or orange. When fogs were bad, traffic stopped. Street lamps had to be lit all day. Walking was dangerous. In 1873, 19 deaths were caused by people falling into the Thames during fog. Crime also increased because of the poor visibility.

People knew that long fogs were bad for health. They were especially harmful to those with breathing problems. Death rates rose during severe fogs. For example, 700 extra deaths were linked to a bad fog in 1873. The fogs of January and February 1880 were very bad. They killed an estimated 2,000 people.

The Problem of Smoke

Pollution and smoke were present all year round. This was due to factories and many home fires. By 1854, London burned about 3.5 million tons of coal each year. By 1880, it was 10 million tons. London was nicknamed "The Smoke" or "The Big Smoke." This name came from people visiting the city from the countryside. One person described it in 1850. They said smoke from factories and homes covered the city like a "pall."

The smoky air quickly dirtied skin and clothes. Furniture and artwork also got dirty. Richer homes needed many servants to keep things clean. The high cost of laundry led to laws to control smoke. The Smoke Nuisance Abatement (Metropolis) Act of 1853 aimed to reduce industrial smoke.

The grass in the Royal Parks turned black from soot. Even the sheep that grazed in Regent's Park were dirty. Some flowers would not grow in London. Many trees died from pollution. The London plane tree was resistant to smoke. It sheds its bark, which helps it resist soot. So, it became a popular tree to plant. Buildings made of brick and stone also turned black. The soot damaged materials like iron and stone. Because of this, terra cotta tiles became popular in the 1880s. They resisted soot and added color to buildings.

People were worried about smoke pollution. Groups were formed to fight it. An exhibition in 1881 showed new technologies to prevent smoke. It displayed smokeless furnaces and stoves. The 1853 law restricted industrial smoke. But a try to control smoke from homes failed in 1884. This left a big source of pollution unregulated.

Famous London Landmarks of the 1800s

Many famous London buildings and landmarks were built in the 19th century. These include:

- Buckingham Palace

- Trafalgar Square

- Nelson's Column

- Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament

- Royal Albert Hall

- Albert Memorial

- Tower Bridge

- Wellington Arch

- Marble Arch

- British Museum

- Natural History Museum

- National Gallery

- Victoria and Albert Museum

|

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |