Buildwas Abbey facts for kids

Buildwas Abbey, Shropshire.

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Monastery of St Mary and St Chad of Buildwas |

| Other names | Communis Monasterii Sancte Marie de Buldewas |

| Order | Cistercian, originally Savigniac |

| Established | 1135 |

| Disestablished | 1536 |

| Mother house | Savigny Abbey |

| Dedicated to | St Mary and St Chad |

| Diocese | Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield |

| Controlled churches |

|

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Roger de Clinton, Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield |

| Important associated figures |

|

| Site | |

| Location | Buildwas, near Ironbridge, Telford, Shropshire, TF8 7BW |

| Coordinates | 52°38′07″N 2°31′42″W / 52.6354°N 2.5284°W |

| Visible remains | Substantial remains of church and claustral buildings. |

| Official name: Buildwas Abbey | |

| Designated: | 8 February 1915 |

| Reference #: | 1015813 |

| Public access | Free entry, 10:00–17:00 every day. |

Buildwas Abbey was a Cistercian monastery located by the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Today, it's about two miles (3 km) west of Ironbridge. It was started in 1135 by the local bishop. At first, it didn't have much money, but it grew richer over time. This was especially true under Abbot Ranulf in the late 1100s and again from the mid-1200s, when it gained lots of land from wealthy families.

The abbots (leaders of the abbey) were often used by the Plantagenet kings to help control Ireland and Wales. The abbey even got a "daughter house" (a smaller monastery it oversaw) in each country. Buildwas Abbey was a place of learning with a big library. It was known for its strict rules until the 1300s, when money problems and a drop in population caused it to decline. Conflicts and political issues in the Welsh Marches (border areas) made things even harder. The abbey was closed down in 1536 by Henry VIII as part of the Dissolution of the monasteries. Today, you can still see many parts of the abbey church and the monks' living areas. English Heritage looks after them.

Contents

How Buildwas Abbey Started

Buildwas Abbey began in 1135 as a Savigniac monastery, which was a strict branch of the Benedictine Order. It was founded by Roger de Clinton, who was the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. The Savigniac group was quite new, only starting in 1112, and was based at Abbey of Savigny in France.

The land where Buildwas Abbey was built used to belong to the diocese. The Domesday Book (a famous survey from 1086) shows that the area, called Buildwas manor, was about one hide (a measure of land). It had nine households, including some slaves and villeins (farm workers tied to the land). There was also a mill and woodland. The abbey was dedicated to St Mary and St Chad, just like Lichfield Cathedral.

The original document that started the abbey is lost. But copies show that Bishop Roger de Clinton gave Buildwas itself, with its woods and cleared land. He also gave land near Shrewsbury and taxes from other areas. The first abbot was named Ingenulf.

King Stephen, who was king at the time, also supported the abbey. In 1138, he confirmed that the abbey was free from many taxes. Stephen was a big fan of the Savigniac group. Another important person, Philip de Belmeis, and his wife Matilda, gave the abbey land at Ruckley. This grant said that all Savigniac monasteries should pray for their family. In 1147, all Savigniac houses, including Buildwas, joined the larger Cistercian order. This change was confirmed by Pope Eugene III in 1148.

Growing Stronger Under Abbot Ranulf

Buildwas Abbey started out small and not very rich. Its early gifts of land were not huge. However, it began to grow and develop under Abbot Ranulf, who became abbot by 1155. His time as abbot was almost the same as the reign of King Henry II.

More Money and Books

A document from King Richard I in 1189, two years after Ranulf died, shows how much land and income the abbey had gained. It lists many new properties, including a house in Chester, a mill near Lichfield, and land in Staffordshire and Derbyshire.

The abbey's growing wealth likely meant its library also grew. Records show 57 books that once belonged to Buildwas Abbey. Many of these were from the 1100s. Two books are even dated to Abbot Ranulf's time. One is a copy of works by Augustine of Hippo from 1167. Another is a glossed (explained with notes) copy of the Book of Leviticus from 1179.

This extra money also helped the abbey build new stone buildings.

Building the Abbey

We don't have many written records about when Buildwas Abbey was built. But it seems to have been constructed between 1152 and 1170. Buildwas and Kirkstall Abbey are examples of the earliest and simplest Cistercian churches in Britain. As builders worked from the east to the west, their designs became more daring. Both churches have a stone tower over the crossing (where the main parts of the church meet), even though Cistercian rules forbade this in 1157.

The main altar area (presbytery) at Buildwas had no side aisles. The side aisles of the nave (main body of the church) had wooden ceilings, not fancy stone ones. The columns in the aisles were simple cylinders. While the style was still Romanesque, some details like the carvings on the tops of columns and windows showed early signs of the Gothic architecture style that came later. The church and monks' living areas were finished within the 1100s. The hospital (infirmary) and abbot's house were still being built around 1220, when the abbey got access to stone and timber from nearby Broseley.

Daughter Houses

In 1156, Abbot Richard of Savigny Abbey gave Abbot Ranulf of Buildwas the responsibility for St. Mary's Abbey, Dublin in Ireland. The next year, Basingwerk Abbey in Flintshire, Wales, was also placed under Buildwas Abbey's care. Both of these had previously belonged to another abbey.

The house in Chester that Bishop Richard Peche gave to Buildwas probably helped Abbot Ranulf travel to Ireland more easily. In 1183–4, records show that Ranulf traveled to Dublin from Chester, which was easy to reach from the abbey. He was traveling "in the king's service," meaning he was helping King Henry II with his plans in Ireland. A writer named Gerald of Wales said that Ranulf was very important in the king's efforts to control Ireland and change the Irish church.

After Ranulf helped in Ireland, King Henry II confirmed that St Mary's Abbey in Dublin belonged to Buildwas in 1174. Ranulf was also involved in plans to start a new Cistercian abbey called Dunbrody Abbey in Ireland. He sent a lay brother (a monk who does manual labor) to check the site, but the report wasn't good. Ranulf decided not to go ahead with it, and instead gave the rights to Dunbrody to St Mary's, Dublin, in 1182.

Abbot Ranulf traveled a lot. In 1187, a record says he "died on his way to the chapter," which means he died while traveling to the general meeting of the Cistercian order in France.

Wealth and Property

Buildwas Abbey became very wealthy in the 1200s. It gathered many estates, giving it a strong financial base. This made it one of the biggest landowners in Shropshire, similar to the county's noble families. The abbey gained a lot of land in the 1240s and 1280s. It built up a group of granges (farm estates run by the monks) along the Rivers Severn and Worfe, and near the Shropshire-Staffordshire border. These were all easy to reach from the abbey, often by boat on the River Severn. This was part of the Cistercian rule that granges should be within a day's journey of the abbey. The abbey also had some larger estates further away, near the Welsh border and in Derbyshire, which were used for grazing animals.

How They Grew Their Estates

One of the most valuable properties near the abbey was the village (vill) of Harnage, granted by Gilbert de Lacy around 1232. Even though there were problems at first, the abbey used legal action and smart deals to secure its position there. The agreement carefully described the land and rights, including pasture for 50 cattle and pigs, and a road for the abbey's wagons to wash sheep and load boats in the River Severn.

Gilbert de Lacy was in debt, and the land was used as security for a loan from a Jewish lender. In 1234, after Gilbert died, the abbot got King Henry III to cancel the pledge. The abbey also had a legal fight with Gilbert's widow, Eva, who claimed part of the estate. But this was settled in 1236. By 1291, the abbey owned all of Harnage.

The abbey used similar methods elsewhere. For example, at Leighton, they first got a mill and fishpond before 1263. Then, in 1282, they gained the advowson (the right to choose the parish priest) of the church, and later took over the church itself, getting its tithes (a portion of crops or income). Soon after, the local lord gave them more land.

Sometimes, Buildwas Abbey had arguments with other monasteries. They feuded with Lilleshall Abbey over land along the River Tern. In 1251, Buildwas accused Lilleshall of destroying its pond. However, Croxden Abbey, another Cistercian house, was more cooperative. In 1287, they swapped a grange (farm) to make administration easier for both abbeys. Buildwas didn't usually try to get control of many churches or their tithes. In 1535, just before it closed, tithes only brought in £6 a year.

In 1292, under King Edward I, many of the abbey's land grants were confirmed. The abbey also had its special right to be free from certain taxes confirmed by the king. However, this didn't stop kings from asking for money. For example, King Edward III asked for money in 1332 for his sister Eleanor of Woodstock's marriage.

Bridges and Tolls

Some people think that a lot of the abbey's money came from tolls (fees) charged on bridges. However, this isn't quite right. The abbey's main income came from raising animals, especially sheep, and selling wool. Buildwas was a big player in the medieval wool trade, selling wool as far away as Italy.

Records show that the abbots were sometimes allowed to charge tolls, but not as a regular income. For example, in 1318, King Edward II gave the abbey the right to charge a toll on goods crossing the bridge at Buildwas for three years. This was to pay for bridge repairs, not to make money for the abbey itself. It was a way for the king to get public works done. In 1325, they got another three-year toll grant to build a bridge over "the water of Cospeford." This would have helped connect the abbey's estates more easily.

The bridge at Buildwas was important for the abbey to connect its lands on both sides of the river. It was also useful for other local traffic. Before the abbey closed, it even had a guest house by the bridge for travelers. The most important bridge over the Severn in the area was at Atcham, and that belonged to Lilleshall Abbey, not Buildwas.

List of Abbey Properties

| Location | Who gave it or owned it first | When it was acquired | What kind of property it was | Approximate location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buildwas manor | Bishop Roger de Clinton | 1135 | Land measured as one hide in Domesday Book. | 52°38′07″N 2°31′38″W / 52.6354°N 2.5273°W |

| Meole | Roger de Clinton and Hugh Nonant | 1135–1192 | A village called Crowmeole, possibly used for pasture. | 52°42′11″N 2°47′21″W / 52.7031°N 2.7892°W |

| Ruckley | Philip de Belmeis and Matilda, his wife. | By 1147 | Land with grazing rights in Tong manor. | 52°39′24″N 2°19′38″W / 52.6566°N 2.3273°W |

| Donington, Shropshire | Richard de Belmeis. | Early, possibly around 1150 | Grazing rights and land for a bridge. | 52°39′21″N 2°19′15″W / 52.6557°N 2.3209°W |

| Little Buildwas | William FitzAlan, Lord of Oswestry | Before 1160. Possibly 1140s. | The village and everything with it: land, water, woods, meadows, and pastures. | 52°38′23″N 2°32′01″W / 52.6398°N 2.5335°W |

| Chester Foregate | Bishop Richard Peche | c.1161 | A messuage or house. | 53°11′29″N 2°53′10″W / 53.1913°N 2.886°W |

| Between Weston and Brockton, Staffordshire | William, son of John Bagoth | 1176 | Land. | 52°42′49″N 2°17′55″W / 52.7135°N 2.2987°W |

| Brockton | Gerald of Brockton and his son | Before 1189 | Land. | 52°43′14″N 2°17′39″W / 52.7205°N 2.2941°W |

| Cosford, Shropshire | Richard of Pitchford | Before 1189 | Services of a man named Richard Crasset. Later exchanged for land. | 52°38′13″N 2°19′09″W / 52.6369°N 2.3191°W |

| Hatton, Shropshire | Adam Treynel, also known as Adam of Hatton, and Reginald, his son. | Before 1189 | Half of the village of Hatton. | 52°38′10″N 2°20′56″W / 52.636°N 2.349°W |

| Walton, Staffordshire | Walter Fitz Herman | By 1189 | Half of the village. | 52°45′22″N 2°17′09″W / 52.7562°N 2.2857°W |

| Cauldon, Staffordshire | William of Cauldon | By 1189. Exchanged in 1287 for Adeney. | Land. | 53°02′07″N 1°52′22″W / 53.0354°N 1.8729°W |

| Ivonbrook, near Grangemill in Derbyshire | Henry Fitz Fulk | By 1189 | Land. | 53°07′27″N 1°38′24″W / 53.1242°N 1.64°W |

| Wentnor, Shropshire | Robert Corbet of Caus | About 1198 | Mill. | 52°31′48″N 2°55′00″W / 52.53°N 2.9168°W |

| Hatton, Shropshire | John de Hemes and Walter, his son. | By 1202 | Lease of land. Later, the rest of the western part of Hatton. | 52°38′04″N 2°21′40″W / 52.6345°N 2.3610°W |

| Wentnor | Robert Corbet of Caus | About 1203–1218 | "Ritton" and "Hulemore": large grazing areas in the Stiperstones. | 52°34′56″N 2°55′47″W / 52.5822°N 2.9296°W |

| Kinnerton | Richard Corbet of Wattlesborough | Between 1217 and 1224 | The entire village of Kinnerton in Wentnor. | 52°33′42″N 2°55′11″W / 52.5616°N 2.9198°W |

| Broseley | Philip de Burwardesley | c. 1220 | Right to quarry stone and cut trees for a road to the River Severn. | 52°37′22″N 2°28′46″W / 52.6229°N 2.4794°W |

| Harnage, near Cound, Shropshire | Gilbert de Lacy, Lord of Cressage | By 1234, probably 1232 | The whole village, with pasture rights and a road for washing sheep and loading boats. | 52°36′58″N 2°38′23″W / 52.6161°N 2.6396°W |

| Kinnerton | Thomas Corbet of Caus | 1236 | Right to fence off the abbey's lands around Kinnerton. | 52°33′49″N 2°56′16″W / 52.5636°N 2.9378°W |

| Hope Bowdler | William, son of William de Chelmick | About 1240 | Half a virgate (a measure of land). | 52°31′36″N 2°46′23″W / 52.5267°N 2.7731°W |

| Ragdon in Hope Bowdler | Robert de Acton, clerk | Between 1245 and 1255. | Land measured as one hide, all of Robert's holding. | 52°31′08″N 2°47′59″W / 52.519°N 2.7998°W |

| Upton | Alan la Zouche, lord of Tong | 1247 | The whole village of Upton, exchanged for wider grazing rights. | 52°39′23″N 2°21′19″W / 52.6563°N 2.3554°W |

| Bicton | William of Bicton | 1247 | Land with a grange site and a road to the highway. | 52°43′39″N 2°50′00″W / 52.7275°N 2.8332°W |

| Stirchley, Shropshire | Osbert Fitz William, lord of Stirchley | 1247 or shortly after. | All of Osbert's interests in Stirchley, including the manor house, garden, and land. | 52°39′37″N 2°26′36″W / 52.6602°N 2.4432°W |

| Hatton, Shropshire | Robert Traynel | About 1248 | The eastern half of Hatton, replacing a lease and giving the abbey control of the manor. | 52°38′01″N 2°21′07″W / 52.6335°N 2.3520°W |

| Benthall, Shropshire | Philip of Benthall | About 1250 | Land with rights to collect stone, coal, and timber. | 52°37′43″N 2°29′56″W / 52.6285°N 2.4988°W |

| Tern | Unknown | By 1251. | Land along the River Tern. | 52°44′48″N 2°33′36″W / 52.7467°N 2.56°W |

| Cressage | Matilda de Lacy and Geoffrey de Genevill | 1253 | A 19-year lease on part of the manor for 200 marks. | 52°38′00″N 2°36′18″W / 52.6334°N 2.605°W |

| Leighton, Shropshire | Robert de Wodecote | By 1263 | A fish pond and mill at Merehaye. | 52°39′01″N 2°34′25″W / 52.6504°N 2.5736°W |

| Blymhill | Henry del Park and his wife, Margery | 1272 | 18 acres of pasture and one of meadow. | 52°42′20″N 2°16′40″W / 52.7055°N 2.2779°W |

| Leighton | Richard de Leighton to Robert Burnell, Lord Chancellor and Bishop of Bath and Wells, who regranted it to Buildwas Abbey. | 1282. Royal confirmation 28 February 1286 | Advowson of Leighton church and one acre of land. | 52°38′34″N 2°34′25″W / 52.6427°N 2.5736°W |

| Albrighton, Shropshire | William, lord of Ryton | By 1284. Confirmed after inspeximus 1 January 1285. | Several areas of farmland and meadow. | 52°37′19″N 2°20′01″W / 52.6219°N 2.3335°W |

| Ryton, Shropshire | Hugh de Weston and Thomas de Marham | Confirmed by William, lord of Ryton, between 1279 and 1284, with royal licence to allienate in Mortmain 1285. | A mill and a meadow. | 52°37′19″N 2°21′24″W / 52.6220°N 2.3567°W |

| Atchley, Shropshire | William, lord of Ryton | By 1286. | Land between Ryton and Cosford. Grazing rights for the abbey's animals. | 52°37′54″N 2°20′02″W / 52.6318°N 2.3339°W |

| Leighton | Richard de Leighton. | 1283/4 | Additional meadowland and grazing rights. | 52°38′34″N 2°34′25″W / 52.6427°N 2.5736°W |

| Adeney, in Edgmond, Shropshire | Croxden Abbey | 1287 | Obtained from Croxden Abbey in exchange for Caldon Grange. | 52°45′49″N 2°26′44″W / 52.7635°N 2.4456°W |

| Bicton | Geoffrey Randulf of Newport | 1288-91 | Initially, the main house of the village and half its ownership. Later, two more houses and land. | 52°43′49″N 2°49′15″W / 52.7303°N 2.8209°W |

| Bonsall, Derbyshire | Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster | 1296 | Grazing for 400 sheep on the moor for a small rent. | 53°07′31″N 1°35′06″W / 53.1253°N 1.5851°W |

| Little Buildwas | Edmund de Lenham and Alice, his wife. | 1302 | Ownership of the manor. | 52°38′23″N 2°32′01″W / 52.6398°N 2.5335°W |

Making Money

Much of the land Buildwas Abbey owned was used for raising animals. In 1291, about 60% of the abbey's income in Shropshire and Staffordshire came from animals, and about 20% from its farmed land. This doesn't include the Derbyshire lands, which had grazing for 400 sheep. Sheep seemed to be the main focus in Shropshire too. The abbey was a major part of the European wool trade, supplying wool to markets as far away as Italy. In the early 1300s, a guide for Italian merchants said Buildwas produced 20 sacks of wool each year.

While the 1200s and early 1300s were a time of great farming by the abbey itself, Buildwas always got some money from rents and leases (renting out land). This was because Cistercians were not allowed to rent to non-monks at first. However, the money it got from churches was very low, less than 5% of its total income in 1535.

Abbots and Monks

Where They Came From

All the known monks at Buildwas Abbey were English. Their surnames, like Boningale and Bridgnorth, suggest most came from Shropshire or nearby areas. Some were from wealthy landowning families. For example, Abbot Henry Burnell, who led the abbey around 1300, was the brother of Philip Burnell, a local lord. Henry even gave his younger brother Hamo a paid job at the abbey. Hamo later sold it back to another abbot, showing how family connections could cause problems.

Learning and Faith

When King Edward III wanted the abbot of Buildwas to help control a Welsh Cistercian abbey in 1328, he said that Buildwas had "wholesome observance and regular institution." This meant he thought the abbey followed its rules well. However, the king had his own political reasons for saying this. He wanted to use the English abbot against the Welsh monastery. Later, the king admitted the real problem in Wales was political fighting between English and Welsh people.

The Cistercian order itself was responsible for checking on the monks' lives at Buildwas. Only one inspection by the mother house of Savigny has a written record. In 1231, Stephen of Lexington visited and issued rules. These rules were the same for Buildwas as for other abbeys, suggesting there were no major problems. They were mostly about monks talking too much or eating too luxuriously, and about improving discipline for new monks and lay brothers.

Monks usually trained to become priests. Buildwas Abbey had at least eight altars, offering many chances to celebrate the Eucharist (Mass). When the abbey's life was interrupted, kings and others worried about the stopping of chantry masses. These were special Masses said for the souls of the dead. People believed that these prayers helped the dead. It wasn't just important people who wanted to be remembered. In 1272, when Henry del Park and his wife gave land to the abbey, they asked that the abbot "remember the same Henry and Margery... in all benedictions and prayers." Kings often asked for prayers for their ancestors and royal family members. The many altars show that these special Masses were a main activity at the church.

Cistercian monks were supposed to only perform their priestly duties within their own abbeys. But in 1307, Buildwas appointed a deacon (a church official) to be the vicar at Leighton parish church. This probably meant a monk had to go there to celebrate Mass. In 1394, they simply sent one of their own monks, William de Weston, to be the chaplain. In 1398, Weston, now a monk and vicar, got permission to go on a pilgrimage to Rome.

The abbey continued its tradition of making and owning books, which Abbot Ranulf probably started. At Balliol College, Oxford, there are four books from Buildwas from the 1200s. These include works by St Bernard and St Jerome. Some of these books have similar decorations, suggesting they were made at Buildwas Abbey itself. Another book, a psalter (a book of psalms), has a note saying it was given to the abbey in 1277 by Master Walter Bridgnorth. It seems Walter might have ordered this book from the abbey for his own use and then left it to the library.

The library mostly had religious works, like the Bible and writings by early Church Fathers. It also had some newer works by authors like Aelred of Rievaulx. There was very little non-religious learning. By the 1400s, some Buildwas manuscripts were being sold in Oxford. This might show a decline in the abbey's spiritual and intellectual life after the hard times of the 1300s.

Abbots and Their Duties

The abbots of Buildwas were important in both political and church matters. Besides looking after their daughter houses in Wales and Ireland, abbots often traveled for Cistercian business. This included going to general meetings, checking new abbey sites, and settling arguments within the order. In 1302, when Edmund de Lenham gave the ownership of Little Buildwas to the abbey, he agreed to escort the abbot "anywhere within the four seas" (meaning anywhere in Britain or overseas). The abbot would pay the costs.

Stephen of Lexington asked the abbot of Buildwas to help reform Irish Cistercian houses starting in 1228. He even suggested giving a small Irish abbey to Buildwas. There are many records of kings granting abbots permission to travel overseas. For example, they got royal protection for travel in 1275, 1278, 1281, and 1286. Special permissions for trips to Ireland were given in 1262 and 1285.

The abbots' political importance is clear because they were often called to the Parliament of England. During King Edward I's reign, abbots of Buildwas were summoned to Parliament several times between 1295 and 1305.

Decline and Closure

In 1521, an inspection by the Cistercian order found Buildwas "very far from virtue in every way." The abbot, Richard Emery, was removed from his position. However, he continued to live at the abbey and receive a corrody (a type of payment, often in food and lodging). The poor behavior and bad relationships with local landowners showed that big changes were coming for the Church. These changes happened with the Dissolution of the monasteries, which closed down monasteries in stages between 1536 and 1540.

In 1535, a survey called Valor Ecclesiasticus found that the abbey's total income was about £123. Buildwas itself brought in about £20, and the rest of the Shropshire estates, which were rented out, were worth about £64. The Walton estate in Staffordshire still brought in £9, but property in Lichfield was only worth a small amount. The large grazing lands in Derbyshire were no longer rented, but Ivonbrook still brought in £6. After expenses, the abbey's net income was about £110. Since this was below the £200 limit, Buildwas was chosen to be closed in 1536, along with other smaller monasteries.

Thomas Cromwell's officials found twelve monks at the abbey in late 1535. Four of them were judged to have poor moral standards. By April 1536, there were only eight monks, all priests, and most were considered "of good conversation" (meaning well-behaved), except for the abbot. There were also 22 servants, four people receiving alms (charity), and three people living on corrodies, including the former abbot.

The Court of Augmentations then valued the abbey and its estates again before selling them. This valuation was similar to the previous one, with some small changes.

After the Closure

The Grey Family Takes Over

In July 1537, Buildwas Abbey and all its estates were given to Edward Grey, 3rd Baron Grey of Powis. He had to pay an annual rent of about £55. The last abbot, Stephen Green, was to receive an annual pension of £16. Lord Powis was not responsible for paying this or the other corrodies the abbey had promised, like the one for the previous abbot, Richard Emery. The last payments for these corrodies and pensions from the government were made in 1553.

Lord Powis died at Buildwas in 1551. He didn't have any official children, but he had a family with Jane Orwell. After Grey's death, Jane Orwell married John Herbert, and they lived at Buildwas. The abbot's house and parts of the abbey's hospital area were changed over time to become Abbey House, which is now a separate private home.

John Herbert had important connections at court. After Lord Powis died, there were long legal battles over his estates. However, Lord Powis had arranged for the Buildwas estates to go to his eldest son, also named Edward Grey, who was John Herbert's stepson. In 1560, the Buildwas estates were officially given to Edward Grey, with John Herbert and other family members providing a financial guarantee.

Herbert was not very involved in the local area. He was a Member of Parliament for Much Wenlock in 1553, but later for a different area. He also had financial problems. In 1564, he was put in prison for debt. He died around 1583.

Around the time the monasteries closed, a local man named Robert Moreton had left some rented properties, including the granges at Brockton and Stirchley (which used to belong to Buildwas Abbey), to the churchwardens of Shifnal parish church. This was to set up a chantry (a fund for a priest to say Masses for the dead). This arrangement had been hidden when chantries were later closed down. When it was discovered, Queen Elizabeth I gave the leases of Brockton and Stirchley to the person who found the fraud.

Later Owners of the Site

The younger Edward Grey lived at Buildwas, and the estate passed to his son, a third Edward Grey, in 1597. This Edward Grey sold the Buildwas estate in a complex way. In 1609, he got permission to sell Buildwas to Thomas Harries, a lawyer. The property was then transferred to Thomas Chamberlayne, another lawyer, in 1612. In 1617, Chamberlayne sold Buildwas to his boss, Lord Ellesmere, who died soon after.

Lord Ellesmere's son, John Egerton, inherited the estate and later became the Earl of Bridgewater. He sold Buildwas in 1649 to Sir William Acton, 1st Baronet, a businessman and former Lord Mayor of London. Sir William died in 1651. Since he had no sons, he left a large inheritance to his daughter Elizabeth. However, some of his estates, including Buildwas, went to a more distant relative, William Acton. William Acton died in 1656, leaving his estates to his daughter Jane. Jane married Walter Moseley, and the house at Buildwas Abbey, later called Abbey House, became the Moseley family's "dower house" (a house for a widow).

The Ruins Today

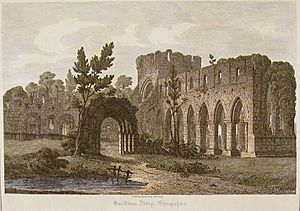

The remaining abbey buildings are now looked after by English Heritage. They are open to the public for free. You can see the church, which still looks much like it did when it was first built. Even though it has no roof and many walls are gone, the remains are considered some of the best-preserved 12th-century Cistercian church examples in Britain.

How the Abbey Changed Over Time

Records show the abbey needed repairs even when it was in use. For example, in 1232, King Henry III gave 30 oak trees from a nearby forest to help repair the church. The main body of the church (nave) and its side aisles had wooden roofs. The abbey was in good condition until it closed. The only major change after the church was built was a large chapel added on the south side around 1400. This might have been for the lay servants who worked there.

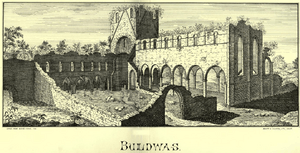

When the abbey closed, the king's officials valued the metal, like the bells and lead, at over £94. Once the lead roof was removed, the wooden roof would have quickly decayed and collapsed. Pictures from the 1700s show how much the abbey had decayed. The outer walls of the aisles were almost gone. Little remained of the cloisters (enclosed courtyards), though some walls were still standing. Artists like Paul Sandby and J. M. W. Turner drew the ruins. Some pictures even showed the church being used as a farm storage building.

Later artists sometimes changed the truth to make the ruins look more "Gothic." For example, John Coney sharpened the arches in his 1825 drawing, even though the real arches were more rounded. By the mid-1800s, people started to see ruins as important historical sites. In 1915, the ruins were protected by law. In 1925, Major H. R. Moseley placed the site in the care of the government, which is now English Heritage. Repairs continue even today.

What You Can See Today

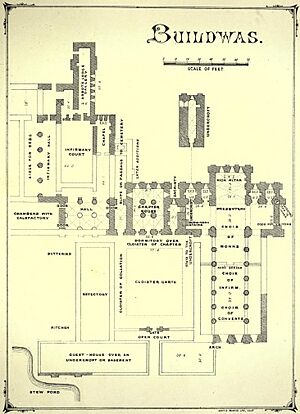

The abbey is a short distance south of the River Severn. The buildings were placed north of the church to use the river for drainage. The church is mostly aligned east-west. The remaining buildings are all made of local sandstone. The wooden parts disappeared long ago. Some parts of the ruins, like the infirmary and abbot's lodging, are on private land and not open to the public. The parts that are open are described below.

The Church

The abbey church is shaped like a cross. It is about 163 feet (50 m) long and 26.7 feet (8.1 m) wide (not including the side aisles). It has:

- A chancel or presbytery (the area around the main altar) at the east end, about 34 feet (10 m) long. It has no side aisles and a flat end, not a rounded one.

- A crossing, which is the central area where the arms of the cross meet. A low, rectangular tower sits above it.

- North and south transepts (the "arms" of the cross), each with two small chapels. At this point, the church is about 84 feet (26 m) wide.

- A nave (the main body of the church) with seven sections (bays) and side aisles. The western five bays are about 70 feet (21 m) long. The eastern two bays and the crossing formed the monks' choir.

- A large, later chapel on the south side.

The roofs and most of the aisle walls are gone, as are the walls of the south chapel.

The arches of the nave are very striking. You can see them as soon as you arrive. Low walls between the arches show that the aisles were separated from the nave. This allowed people to move around during services. The columns are huge and round, except for the eastern pair. They are simple, with scalloped carvings on the tops of the columns. The arches are bluntly pointed. Above them is a tall clerestory (a row of windows high up), but there was never a triforium (a raised gallery) inside the nave. The clerestory windows have rounded tops. There are two windows at the very top of the western end of the nave, but no entrance below them. Inside, the floor drops at the western end, which was likely for the lay brothers.

The quire or monks' choir took up the two eastern bays of the nave and the crossing. You can see the foundation of the rood screen (a screen that separated the choir from the rest of the nave) between the second columns. There are also signs of altars that were next to the screen entrance. The central tower is supported by corbels (stone supports) high in the walls. It had only two small windows on each side for light. The four transept chapels are similar in design. Each had an ambry (a small cupboard) and a low piscina (a basin for washing sacred vessels) for the many chantry masses.

The presbytery (main altar area) was originally separated from the rest of the church. The three eastern windows were added later, replacing an earlier pair. The altar would have stood forward from the east wall. There are three sedilia (seats for the priest and assistants) built into the south wall. Next to these is the piscina for ritual washing.

The Cloister

The cloister court is north of the church and at a lower level. The foundations of its walls remain on three sides. There is no sign of a cloister arcade (a covered walkway with arches). The east side is the best preserved. The upper floor, which held the dorter (monks' sleeping quarters), is gone. The lower floor has a sacristy, chapter house, and parlour, plus an entrance to a crypt.

The crypt is entered by steps from the south end of the east cloister. It is under the north transept. Its roof is a groin vault (a type of arched ceiling). Its original purpose is unknown, but it might have been for private talks, storing clothes, or preparing bodies. Today, it holds a small collection of items found during digs, but it's not always open.

The sacristy was for storing vestments (priestly robes), chalices, patens (sacred vessels), and other church items. It has a vaulted roof. It's a narrow space, about 10.5 feet (3.2 m) wide. Its north wall has two small storage cupboards called ambries. For easy access to sacred items, the sacristy connects to the church through a doorway into the north transept. Another doorway in the east wall, which used to be a window, leads to the cemetery (now part of a private home).

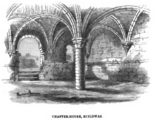

The chapter house was where the monks met daily to read the monastic rule and the martyrology (a list of saints). They also confessed their sins there. You enter through a doorway from the cloister. The floor is much lower than the cloister, requiring five steps down. Four columns support a beautiful ribbed vaulted roof, which is the most impressive roof still standing. The room is about 41.5 feet (12.6 m) by 31.5 feet (9.6 m). It is lit by three windows in the east wall. The tiled floor was removed after the abbey closed but has been partly restored.

The parlour was a room where monks were allowed to talk. It has a ribbed vaulted roof. Its entrance from the cloister is a rounded doorway. There are two more doorways: one to the outside and one to the undercroft (a vaulted basement).

North of the parlour, the ruins become less visible and are on private land. There would have been a staircase to the sleeping quarters above the undercroft. The north range would have held the refectory (dining hall), which was important for community life. The kitchen was probably at the west end. The west range held the lay brothers' quarters. This part was behind the west cloister and had three floors, though only the large basement remains.

Images for kids

-

Edward III, as depicted by his statue in Westminster Abbey.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |