Coral reef fish facts for kids

Coral reef fish are fish that live in or very close to coral reefs. Coral reefs are like busy underwater cities, full of amazing plants and animals. They have a huge variety of life, called biodiversity. Among all the creatures, the fish are super colorful and fun to watch. Hundreds of different kinds of fish can live in a small part of a healthy reef. Many of them are hidden or blend in very well with their surroundings. Reef fish have developed many clever ways to survive in these crowded reefs.

Even though coral reefs cover less than one percent of the world's oceans, they are home to about 25 percent of all ocean fish species! Reefs are very different from the wide-open ocean, which makes up most of the world's waters.

Sadly, coral reefs and the fish that live there are in danger. Their homes are being damaged, there's more pollution, and too much overfishing (including harmful fishing methods) are big threats.

Contents

Amazing Reef Fish Adaptations

Coral reefs have been forming for millions of years. Algae, invertebrates (like crabs), and fish have all grown and changed together. This has made reefs very busy and complex places. Fish have found many clever ways to survive here. Most reef fish are ray-finned fish. This means they have sharp, bony rays and spines in their fins. These spines are great for defense. When a fish puts them up, they can often lock them in place or even be poisonous. Many reef fish also have special colors and patterns to hide from predators.

Reef fish also have smart behaviors. Small reef fish hide from predators in cracks in the reef. They also swim together in groups called schools. Many reef fish stay in a small area where they know every hiding spot. Other fish swim around the reef in schools to find food. But they return to a known hiding spot when they need to rest. Even resting small fish can be attacked. So, many fish, like triggerfish, squeeze into a small hiding place and use their spines to wedge themselves in.

For example, the yellow tang is a fish that eats algae from the reef. They also help sea turtles by cleaning algae off their shells! Yellow tangs don't like other fish that look like them. When scared, the usually calm yellow tang can put up spines in its tail. It can then slash at an enemy with quick side-to-side movements.

-

The calm yellow tang can use spines in its tail to slash at enemies.

Where Reef Fish Live and How Many There Are

Coral reefs have the most different kinds of fish found anywhere on Earth. There might be as many as 6,000 to 8,000 species living in coral reefs around the world!

Scientists have wondered for a long time why so many fish species live on coral reefs. There are many ideas, but no single answer. It's probably a mix of things. These include the many different places to live on a reef, the wide variety of food available, and how young fish settle on the reef.

There are two main areas where coral reefs grow: the Indo-Pacific (which includes the Pacific and Indian Oceans, plus the Red Sea) and the tropical western Atlantic (also called the Caribbean). Each area has its own unique reef fish. The Indo-Pacific is much richer, with an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 species. The Caribbean has about 500 to 700 species.

-

Among goby species, the seven-figure pygmy goby lives for less than 60 days, making it the shortest-lived vertebrate.

-

Sea horses are some of the slowest-moving fish. The dwarf seahorse moves about five feet per hour.

How Reef Fish Are Built

Body Shape

Most reef fish have body shapes that are different from fish that live in the open ocean. Open ocean fish are usually built for speed, like torpedoes, to cut through the water. Reef fish live in the tight, complex spaces of coral reefs. Here, being able to turn and move quickly is more important than swimming fast in a straight line. So, coral reef fish have bodies that help them dart and change direction. They can trick predators by dodging into cracks in the reef or playing hide-and-seek around corals.

Many reef fish, like butterflyfish and angelfishes, have bodies that are tall and flat like a pancake. Their fins are specially designed to work with their flat bodies to help them move very well.

Colors and Patterns

Coral reef fish show off a huge variety of amazing and sometimes strange colors and patterns. This is very different from open ocean fish, which are usually silvery and blend in with the water.

These patterns have different jobs. Sometimes they help the fish hide when it rests in places that match its background. Colors can also help fish recognize each other when they are mating. Some clear, bright patterns are used to warn predators that the fish has poisonous spines or flesh.

The foureye butterflyfish gets its name from a large dark spot on each side of its body, near its tail. This spot has a bright white ring around it, looking like a fake eye. A black stripe on its head goes through its real eye, making it hard to see. This can make a predator think the fish is bigger than it is. It also confuses the predator about which end is the front! When threatened, the butterflyfish usually tries to swim away. It puts its fake eye closer to the predator than its head. Most predators aim for the eyes. This fake eye tricks the predator into thinking the fish will swim tail-first. If it can't escape, the butterflyfish might turn to face its attacker, head down and spines up. This might scare the other animal or remind the predator that the butterflyfish is too spiny to eat comfortably.

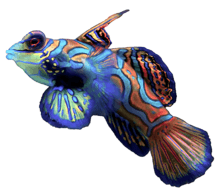

The colorful Synchiropus splendidus (right) is hard to see because it stays near the bottom and is small, only about 6 cm long. It eats small crabs and other tiny animals. It's a popular fish for aquariums.

Just as some prey fish use colors to hide, some ambush predators (hunters that wait) use camouflage to surprise their prey. The tasseled scorpionfish is an ambush predator that looks like a part of the seafloor covered in coral and algae. It waits on the bottom for crabs and small fish, like gobies, to swim by. Another ambush predator is the striated frogfish (right). They lie on the bottom and wave a noticeable worm-like lure that grows above their mouth. They are usually about 10 cm long. They can also puff themselves up like pufferfish.

Gobies hide from predators by tucking into coral cracks or burying themselves partly in the sand. They constantly look for predators with eyes that can move separately. The camouflage of the tasseled scorpionfish can stop gobies from seeing them until it's too late.

The clown triggerfish has strong jaws to crush and eat sea urchins, crabs, and hard-shelled snails. Its lower side has large, white spots on a dark background. Its upper side has black spots on yellow. This is a type of countershading. From below, the white spots look like the bright surface of the water above. From above, the fish blends in more with the coral reef below. Its bright yellow mouth might scare away possible predators.

-

The foureye butterflyfish has fake eyes on its back end to confuse predators.

-

The frogfish is an ambush predator that looks like an algae-covered stone.

-

Gobies are very careful, but they can still miss seeing a tasseled scorpionfish until it's too late.

How Reef Fish Find Food

Many reef fish species have developed different ways to eat. They have special mouths, jaws, and teeth that are perfect for their main food sources on coral reefs. Some fish even change what they eat as they grow up. This makes sense because there's a huge variety of food available around coral reefs.

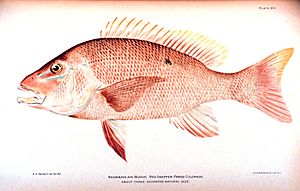

For example, butterflyfish mainly eat coral polyps or parts of small invertebrate animals. Their mouths stick out like tweezers. They have tiny teeth that let them nip off parts of their prey. Parrotfish eat algae growing on reef surfaces. They have mouths like beaks that are good for scraping off their food. Other fish, like snapper, eat many different things. They have normal jaws and mouths that let them hunt a wide range of animals, including small fish and invertebrates.

Meat Eaters (Carnivores)

Fish that eat meat (carnivores) are the most common type of feeder among coral reef fish. There are many more carnivore species on reefs than plant eaters. Competition among carnivores is strong. This makes the reef a dangerous place for their prey. Hungry predators hide or patrol every part of the reef, day and night.

Some fish on reefs are general carnivores. They eat many different kinds of animals. These fish usually have large mouths that can open very quickly. This sucks in nearby water and any unlucky animals in it. The water is then pushed out through their gills with their mouth closed, trapping the helpless prey. For example, the bluestripe snapper eats many things. Its diet includes fish, shrimp, crabs, mantis shrimp, cephalopods (like squid), and tiny crustaceans that float in the water. They also eat some plants and algae. What they eat changes with their age, where they live, and what prey is available.

Goatfish are always looking for food on the bottom. They use two long, sensitive whiskers (called barbels) that stick out from their chins. They use these to search through the sand for food. Like goats, they will eat anything edible: worms, crabs, snails, and other small invertebrates. The yellowfin goatfish often swims with the blue-striped snapper. The yellowfins change their color to match the snapper. This probably helps them stay safe from predators, because goatfish are eaten more often than bluestripe snapper. At night, the schools break up, and individual goatfish go their separate ways to search the sands. Other fish that hunt at night follow the active goatfish, waiting for any food they miss.

Moray eels and coral groupers are known to hunt together. Groupers are fish that can change sex. They swim in groups called harems. If there is no male, the largest female in the group will change into a male.

-

Adult coral trout hunt many reef fish, especially damselfish. Young ones mostly eat crabs.

-

Coral grouper sometimes hunt with giant morays.

Specialized Meat Eaters

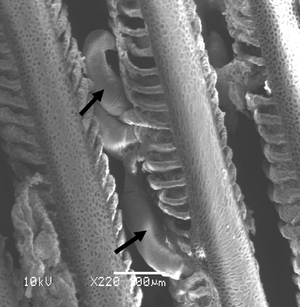

Large schools of small fish, like surgeonfish and cardinalfish, swim around the reef eating tiny zooplankton (tiny animals floating in the water). These small fish are then eaten by bigger fish, like the bigeye trevally. Fish get many benefits from swimming in schools. One benefit is defense against predators, because each fish is looking out for danger. Schooling fish have amazing ways of swimming together that confuse predators. They have special sensors along their sides, called lateral lines. These let them feel each other's movements and stay in sync.

Bigeye trevally also form schools. They are fast hunters that patrol the reef in groups. When they find a school of small fish, like cardinalfish, they surround them and push them close to the reef. This makes the prey fish panic and their school breaks apart, making them easy for the trevally to attack.

-

Many small reef fish benefit from schooling.

-

Cardinalfish swim in schools to protect themselves from trevally.

-

Bigeye trevally hunt cardinalfish in groups. They push them against the reef, and when the cardinalfish panic, the trevally pick them off.

The titan triggerfish can move fairly large rocks when it's looking for food. Smaller fish often follow it to eat the leftovers. They also use a jet of water to uncover sand dollars buried in the sand.

Barracuda are fierce predators that eat other fish. They have very sharp, pointed teeth that help them tear their prey apart. Barracuda patrol the outer reef in large schools. They are extremely fast swimmers with smooth, torpedo-shaped bodies.

Porcupinefish are medium to large fish, usually found swimming among or near coral reefs. They can inflate their bodies by swallowing water. This makes them much bigger, so only predators with very large mouths can eat them.

Fish can't clean themselves. Some fish specialize as cleaner fish. They set up "cleaning stations" where other fish can come to have their parasites eaten off. The "resident fish doctor and dentist on the reef is the bluestreak cleaner wrasse". The bluestreak has a bright blue stripe that makes it easy to spot. It acts in a special way that attracts bigger fish to its cleaning station. As the bluestreak eats the parasites, it gently tickles its client. This seems to make the bigger fish come back for regular cleanings.

The reef lizardfish has a slimy coating that helps it swim faster. It also protects it from some parasites. But other parasites actually like to eat this mucus! So, lizardfish visit the cleaner wrasse, which cleans the parasites from their skin, gills, and mouth.

-

The Emperor angelfish eats coral sponges.

-

The titan triggerfish is followed by small fish like orange-lined triggerfish and moorish idol that eat its leftovers.

-

Two small cleaner wrasses cleaning a larger fish at a cleaning station.

-

The reef lizardfish has a mucus coating that reduces drag. But some parasites like to eat the mucus.

Plant Eaters (Herbivores)

Herbivores are animals that eat plants. The four largest groups of coral reef fish that eat plants are parrotfish, damselfish, rabbitfish, and surgeonfish. All of them mainly eat tiny and larger algae that grow on or near coral reefs.

Algae can cover reefs in many colors and shapes. Algae are primary producers. This means they are like plants that make their own food using sunlight, carbon dioxide, and other simple nutrients. Without algae, everything on the reef would die. One important group of algae, called bottom-dwelling algae, grows over dead coral and other surfaces. These areas become like grazing fields for herbivores such as parrotfish.

Parrotfish are named for their parrot-like beaks and bright colors. They are large herbivores that graze on the algae growing on hard, dead corals. They have two pairs of crushing jaws and their beaks. They can grind up pieces of algae-covered coral, digest the algae, and then release the coral as fine sand.

Smaller parrotfish are fairly defenseless plant eaters. They are not well protected against predators like barracuda. They have learned to find safety by schooling, sometimes with other species like schooling rabbitfish. Spinefoot rabbitfish are named for their venomous spines, which they use for defense. They are rarely attacked by predators. Spines are a last resort. It's better to avoid being seen by a predator in the first place, rather than having to fight. So, rabbitfish have also developed amazing color-changing abilities.

Damselfish are a group of species that eat tiny animals floating in the water (zooplankton) and algae. They are important small fish for larger predators to eat. They are small, usually about five centimeters long. Many species are aggressive towards other fish that also eat algae, like surgeonfish. Surgeonfish sometimes use schooling as a way to deal with attacks from single damselfish.

-

Relatively defenseless parrotfish eat algae.

-

Fierce barracuda hunt parrotfish in schools.

Fish Working Together (Symbiosis)

Symbiosis means two different species have a close relationship. This relationship can be:

- Mutualistic: Both species benefit.

- Commensalistic: One species benefits, and the other is not affected.

- Parasitic: One species benefits, and the other is harmed.

An example of commensalism is between the hawkfish and fire coral. Hawkfish can sit on fire corals without getting hurt because of their large, skinless fins. Fire corals are not true corals. They are hydroids that have stinging cells called nematocysts, which would normally prevent close contact. The protection from fire corals means the hawkfish has a good view of the reef. It can safely watch its surroundings like a hawk. Hawkfish usually stay still. But they dart out to grab crabs and other small invertebrates that pass by. They are mostly alone, but some species form pairs and share a coral head.

A stranger example of commensalism is between the thin, eel-shaped pinhead pearlfish and a certain type of sea cucumber. The pearlfish enters the sea cucumber through its rear end. It spends the day safely inside the sea cucumber's gut. At night, it comes out the same way and eats small crustaceans.

Sea anemones are common on reefs. The tentacles of sea anemones are covered with tiny harpoons (nematocysts) filled with toxins. These are very good at keeping most predators away. However, saddle butterflyfish, which can be up to 30 cm long, have developed a way to resist these toxins. Saddle butterflyfish usually flutter gently. But when their favorite food, sea anemones, are around, they become very active. The butterflyfish dash in and out, tearing off the anemone tentacles.

-

Saddle butterflyfish are not affected by sea anemone toxins.

There is a mutualistic relationship between sea anemones and clownfish. This gives the sea anemones extra protection. They are guarded by fierce clownfish, who are also immune to the anemone toxins. To get their meal, butterflyfish must get past these protective clownfish. Even though they are smaller, the clownfish are not scared. An anemone without its clownfish will quickly be eaten by butterflyfish. In return, the anemones protect the clownfish from their predators, who are not immune to anemone stings. As an added benefit to the anemone, waste ammonia from the clownfish helps feed tiny algae that live inside the anemone's tentacles.

Like all fish, coral reef fish have parasites. Because coral reef fish have so many different species, their parasites also come in a huge variety. Some of these parasites have complex life cycles, meaning they live on several different hosts, like sharks or snails. The many different species on coral reefs make the relationships between parasites and their hosts very complex.

Dangerous Fish (Toxicity)

Many reef fish are toxic. Toxic fish have strong toxins in their bodies. There's a difference between poisonous fish and venomous fish. Both types have strong toxins. But the difference is how the toxin gets into another animal. Venomous fish deliver their toxins (called venom) by biting, stinging, or stabbing. This causes an envenomation. Venomous fish don't always cause poisoning if you eat them, because the venom is often destroyed in the stomach. On the other hand, poisonous fish have strong toxins that are not destroyed by digestion. This makes them dangerous to eat.

Venomous fish carry their venom in special glands. They use different ways to deliver it, like spines, sharp fins, barbs, or fangs. Venomous fish tend to be either very easy to see, using bright colors to warn enemies, or very well hidden and perhaps buried in the sand. Besides defense or hunting, venom might help bottom-dwelling fish by killing bacteria that try to get into their skin. Few of these venoms have been studied. They are a resource that could be used to find new medicines.

The most venomous known fish is the reef stonefish. It's amazing at hiding among rocks. It's an ambush predator that sits on the bottom, waiting for prey to come close. It doesn't swim away if disturbed. Instead, it puts up 13 venomous spines along its back. For defense, it can shoot venom from any or all of these spines. Each spine is like a tiny needle, delivering venom from two sacs attached to it. The stonefish can choose whether to shoot its venom. It does so when it feels threatened or scared. The venom causes severe pain, paralysis, and tissue damage. It can even be deadly if not treated. Despite its strong defense, the stonefish does have predators. Some bottom-feeding rays and sharks with crushing teeth eat them, as does the Stokes's sea snake.

-

The spotted trunkfish releases a ciguatera toxin from its skin glands when touched.

-

Like many other top reef fish, the giant moray can cause ciguatera poisoning if eaten.

Unlike the stonefish, which can shoot venom, the lionfish only releases venom when something hits its spines. Lionfish are not from the US coast, but they have appeared around Florida and spread up to New York. They are attractive aquarium fish, sometimes used to stock ponds. They might have been washed into the sea during a hurricane. Lionfish can aggressively dart at divers and try to sting their facemasks with their venomous spines.

The spotted trunkfish is a reef fish that releases a clear ciguatera toxin from glands on its skin when touched. The toxin is only dangerous if eaten, so it doesn't immediately harm divers. However, predators as large as nurse sharks can die from eating a trunkfish. Ciguatera toxins seem to build up in the top predators of coral reefs. Many of the Caribbean groupers and barracuda, for example, can have enough of this toxin to cause serious symptoms in humans who eat them. What makes this especially dangerous is that these fish might only be toxic at certain sizes or in certain places. This makes it hard to know if they are safe to eat. In some places, this leads to many cases of ciguatera poisoning among people living on tropical islands.

The stargazer buries itself in sand. It can give electric shocks and is venomous. It's a special food in some cultures (the venom is destroyed when cooked). You can find it for sale in some fish markets with its electric organ removed. People have called them "the meanest things in creation."

The giant moray is a reef fish at the top of the food chain. Like many other top reef fish, it is likely to cause ciguatera poisoning if eaten. Outbreaks of ciguatera poisoning from large, meat-eating reef fish between the 11th and 15th centuries might be a reason why Polynesians moved to Easter Island, New Zealand, and possibly Hawaii.

Reef Sharks and Rays

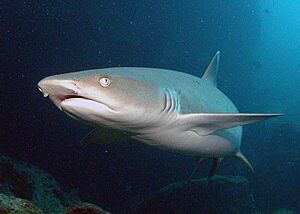

Whitetip, blacktip, and grey reef sharks are the main sharks in the coral reef ecosystems of the Indo-Pacific. Coral reefs in the western Atlantic Ocean are mostly home to the Caribbean reef shark. These sharks are all types of requiem shark. They have strong, smooth bodies typical of requiem sharks. They are fast-swimming, agile predators. They mainly eat free-swimming bony fish and cephalopods (like squid). Other types of reef sharks include the Galapagos shark, the tawny nurse shark, and hammerheads.

The whitetip reef shark is a small shark, usually less than 1.6 meters (5.2 feet) long. It is found almost only around coral reefs. You can see it near coral heads and ledges, or over sandy areas, in lagoons, or near drop-offs to deeper water. Whitetips like very clear water and rarely swim far from the bottom. They spend most of the daytime resting inside caves. Unlike other requiem sharks, which usually need to swim constantly to breathe, these sharks can pump water over their gills and lie still on the bottom. They have thin, flexible bodies. This allows them to wiggle into cracks and holes to get prey that other reef sharks can't reach. However, they are not very good at catching food floating in open water.

Whitetip reef sharks don't go into very shallow water like the blacktip reef shark. They also don't stay in the outer reef like the grey reef shark. They generally stay in a small, local area. A single shark might use the same cave for months or even years. During the day, a whitetip reef shark's home area is small. At night, this area gets bigger.

The whitetip reef shark is very good at sensing smells, sounds, and electrical signals from possible prey. Its eyes are better at seeing movement and contrast than small details. It is especially sensitive to low-frequency sounds (like 25–100 Hz), which sound like struggling fish. Whitetips hunt mainly at night, when many fish are asleep and easy to catch. After dark, a group of sharks might hunt the same prey. They will cover every way out from a coral head. Each shark hunts for itself and competes with the others in its group. They mainly eat bony fish, including eels, squirrelfish, snapper, damselfish, parrotfish, surgeonfish, triggerfish, and goatfish. They also eat octopus, spiny lobsters, and crabs. Important predators of the whitetip reef shark include tiger sharks and Galapagos sharks.

The blacktip reef shark is usually about 1.6 meters (5.2 feet) long. It is often found over reef ledges and sandy areas. But it can also go into brackish (slightly salty) and freshwater. This shark likes shallow water. The whitetip reef shark and the grey reef shark prefer deeper water. Younger sharks like shallow sandy areas. Older sharks spend more time around reef ledges and near reef drop-offs. Blacktip reef sharks stay strongly attached to their own area. They might stay there for several years. A study in the central Pacific found that the blacktip reef shark had a home range of about 0.55 square kilometers (0.21 square miles). This is one of the smallest home ranges for any shark species. The size and location of their range don't change with the time of day. The blacktip reef shark swims alone or in small groups. Large groups have also been seen. They are active predators of small bony fish, cephalopods, and crabs. They also eat sea snakes and seabirds. Blacktip reef sharks are hunted by groupers, grey reef sharks, tiger sharks, and even other blacktip reef sharks. In one area, adult blacktip reef sharks avoid tiger sharks by staying out of the deeper central lagoon.

Grey reef sharks are usually less than 1.9 meters (6.2 feet) long. Even though they are not huge, grey reef sharks actively chase away most other shark species from their favorite places. In areas where this shark lives with the blacktip reef shark, the blacktip stays in shallow areas. The grey reef shark usually stays in deeper water. But where blacktips are not present, grey reef sharks are often found in shallow areas. Many grey reef sharks have a home range in a specific part of the reef. They keep returning to this area. However, they are social rather than territorial. During the day, these sharks often form groups of 5–20 sharks near coral-reef drop-offs. They split up in the evening when they start to hunt. They are found over continental and island shelves. They prefer the sides of coral reefs that are away from the current. These areas have clear water and rocky shapes. They are often found near the drop-offs at the outer edges of the reef. They are less common inside lagoons. Sometimes, this shark might swim several kilometers out into the open ocean.

Shark researcher Leonard Compagno explained how these three shark species relate: "The grey reef shark... lives in different small areas than the blacktip reef sharks. Around islands where both species live, the blacktip stays in shallow areas, while the grey reef shark is usually found in deeper areas. But where the blacktip is not there, the grey reef shark is commonly found in the shallow areas... The grey reef shark is good at catching fish that are not on the bottom, much better than the whitetip. But the whitetip is much better at getting prey from cracks and holes in reefs."

The Caribbean reef shark can be up to 3 meters (10 feet) long. It is one of the largest apex predators (top predators) in the reef ecosystem. Like the whitetip reef shark, they have been seen resting still on the sea bottom or inside caves. This is unusual behavior for requiem sharks. Caribbean reef sharks play a big role in shaping the communities on Caribbean reefs. They are more active at night. There is no sign that their activity or movement changes with the seasons. Young sharks tend to stay in a small area all year. Adult sharks move over a wider area. The Caribbean reef shark eats many different reef-dwelling bony fish and cephalopods. They also eat some rays, like eagle rays and yellow stingrays. Young sharks eat small fish, shrimp, and crabs. In turn, young sharks are hunted by larger sharks like the tiger shark and the bull shark.

-

The great hammerhead uses its hammer-shaped head to find electric signals from stingrays buried in the sand. It also uses it to pin them down.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |