Pelagic fish facts for kids

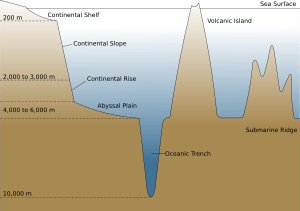

Pelagic fish are amazing fish that live in the open ocean or large lakes. They don't stay near the bottom or close to the shore. This is different from demersal fish, which live on or near the seabed, and reef fish, which live around coral reefs.

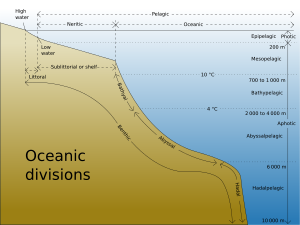

The open ocean is the biggest water home on Earth. It's huge, covering 1,370 million cubic kilometers! About 11% of all known fish species live here. The ocean is very deep, with an average depth of 4,000 meters. Most of this water is deep and dark.

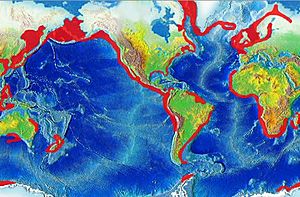

Pelagic fish can be split into two main groups: coastal pelagic fish and oceanic pelagic fish. Coastal fish live in the shallower, sunny waters above the continental shelf. Oceanic fish live in the huge, deep waters far away from the coast. Even so, oceanic fish might sometimes swim closer to shore.

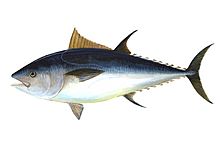

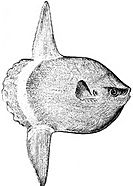

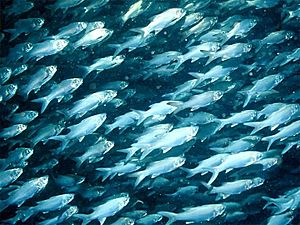

Pelagic fish come in all sizes. Some are small coastal forage fish, like herrings and sardines. Others are huge apex predators, like bluefin tuna and oceanic sharks. They are usually fast swimmers with smooth, sleek bodies. They can swim long distances on their migrations. Many pelagic fish swim together in huge schools. Some, like the giant ocean sunfish, swim alone. These big fish can weigh over 500 kilograms and sometimes just float with the ocean currents, eating jellyfish.

Contents

Fish in the Sunlit Zone (Epipelagic Fish)

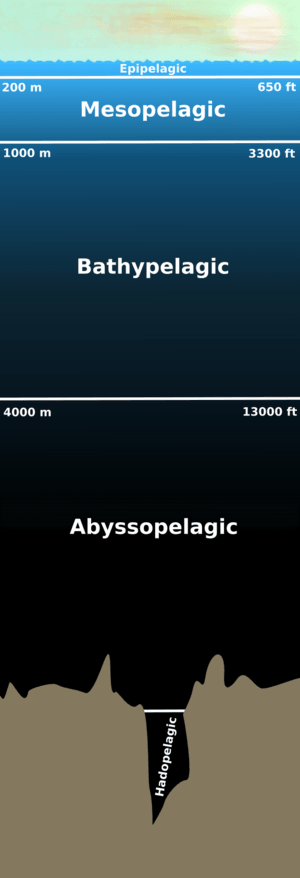

Epipelagic fish live in the epipelagic zone. This is the top layer of the ocean, from the surface down to about 200 meters. It's also called the sunlit zone because sunlight reaches here. This light allows tiny plants called phytoplankton to make their own food using sunlight.

This zone is a huge home for most pelagic fish. It's bright, so fish can use their eyesight to hunt. Waves keep the water mixed and full of oxygen. It's also a good place for algae to grow. But this zone doesn't have many different types of places to hide. Because of this, it has less than 2% of the world's known fish species. Many parts of this zone don't have enough nutrients for fish. So, epipelagic fish often gather in coastal waters. Here, nutrients from land runoff or upwelling (where deep, nutrient-rich water rises) make the area better for them.

Epipelagic fish are generally either small forage fish or larger predator fish that eat them. Forage fish swim in schools and eat tiny organisms by filtering water. Most epipelagic fish have streamlined bodies. This helps them swim long distances. Both predator and forage fish usually have similar body shapes. Predator fish often have large mouths, smooth bodies, and strong, forked tails. Many use their eyesight to hunt smaller fish or tiny animals. Others filter feed on plankton.

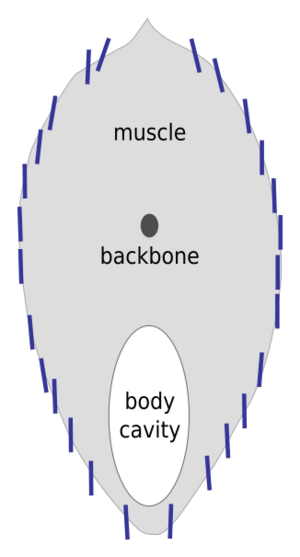

Most epipelagic fish, both predators and prey, use a type of camouflage called countershading. This means they are silvery. Their shiny scales act like tiny mirrors. This helps them blend in by reflecting the light around them. In the middle of the ocean, light comes from above. So, if a fish has vertical mirrors on its sides, it becomes almost invisible from the side.

In shallower waters, the mirrors on fish need to reflect different colors of light. Fish have special crystals in their scales that help with this. Even though there aren't many species, epipelagic fish are very common. What they lack in variety, they make up for in numbers. Forage fish exist in huge amounts. The larger fish that eat them are often caught for food. Together, epipelagic fish support the most valuable fisheries in the world.

Many forage fish can switch how they eat. They might pick out individual tiny creatures or fish larvae. Then, if it's better for them, they can switch to filtering tiny plants from the water. Fish that filter feed often have long, thin gill rakers. These act like a sieve to catch small organisms. Some of the biggest epipelagic fish, like the basking shark and whale shark, are filter feeders. Some of the smallest, like adult sprats and anchovies, are also filter feeders.

Clear ocean waters usually have little food. Areas with lots of food tend to be a bit cloudy from many tiny plants growing. This cloudiness attracts filter feeders, which then attract bigger predators. Tuna fishing is often best when the water is a bit cloudy, but not too much.

Fish Around Floating Things

Epipelagic fish are very drawn to floating objects. They gather in large numbers around things like drifting trash, rafts, jellyfish, and floating seaweed. These objects seem to give them something to look at in the wide-open ocean. Floating objects can also offer a safe place for young fish to hide from predators. Lots of drifting seaweed or jellyfish can greatly help young fish survive.

Many young coastal fish use seaweed for shelter and food. Drifting seaweed, especially a type called Sargassum, creates a special home. It has its own shelter and food, and even unique animals living in it, like the sargassum fish. Jellyfish are also used by young fish for shelter and food, even though jellyfish can sometimes eat small fish.

Fishermen use this behavior to catch fish. They use objects called fish aggregating devices (FADs). FADs are rafts or other objects that float on the surface or just below it. Fishermen in the Pacific and Indian oceans set up FADs. Then they use large nets to catch the fish that gather around them.

Studies have shown that young bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna gather very close to these FADs. Farther out, larger tuna also gather. Other fish use FADs too.

Bigger fish, even predators like the great barracuda, often have smaller fish swimming with them. These smaller fish stay close in a safe way. Even divers who stay in the water for a long time often attract fish. Small fish come close, and larger fish watch from a distance. Marine turtles can also act as moving shelters for small fish.

Coastal Fish (Neritic Fish)

Coastal fish live in the waters near the coast, above the continental shelf. Since the continental shelf is usually less than 200 meters deep, coastal fish that are not bottom-dwellers are usually epipelagic fish. This means they live in the sunny, top layer of the ocean.

Coastal epipelagic fish are some of the most common fish in the world. They include forage fish and the predator fish that eat them. Forage fish do well in these coastal waters. This is because upwelling and runoff from the land bring many nutrients. Some coastal fish live part-time in streams, estuaries, and bays, but most spend their whole lives in this zone.

Oceanic Fish

Oceanic fish live in the open waters that are not above the continental shelf. They are different from coastal fish, which live over the shelf. However, these two groups can mix. There are no clear lines between coastal and ocean areas. Many epipelagic fish move between coastal and oceanic waters during different parts of their lives.

Oceanic epipelagic fish can be true residents, partial residents, or accidental residents. True residents live their whole lives in the open ocean. Only a few species are true residents, such as tuna, billfish, flying fish, sauries, pilotfish, remoras, dolphinfish, ocean sharks, and ocean sunfish. Most of these fish travel back and forth across open oceans. They rarely go over continental shelves. Some true residents stay near drifting jellyfish or seaweeds.

Partial residents are in three groups:

- Young fish that live in the zone only when they are small (drifting with jellyfish and seaweeds).

- Adult fish that live in the zone only when they are grown (like salmon, flying fish, dolphin, and whale sharks).

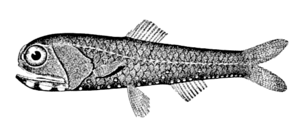

- Deep-water fish that swim up to the surface waters every night (like lanternfish).

Accidental residents are fish from other areas that are carried into the zone by ocean currents.

-

The huge ocean sunfish lives in the open ocean. It sometimes floats with the current, eating jellyfish.

-

The giant whale shark also lives in the open ocean. It filters tiny plants and animals from the water. It sometimes dives deep into the twilight zone.

-

Lanternfish are partial residents. They hide in deep waters during the day. At night, they swim up to the surface to feed.

Deep Water Fish

In the deep ocean, the waters go far below the sunlit zone. Here, very different types of pelagic fish live. They are specially adapted to these deep zones.

In deep water, there's a constant shower of mostly dead bits falling from the upper ocean layers. This is called marine snow. It includes dead plankton, tiny organisms, bits of waste, sand, and dust. These "snowflakes" grow as they fall. They can travel for weeks before reaching the ocean floor. However, most of the good parts of marine snow are eaten by tiny living things and other filter feeders within the first 1,000 meters. This means marine snow is the main food source for deep-sea ecosystems. Since sunlight can't reach them, deep-sea animals rely heavily on this marine snow for energy.

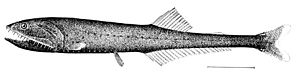

Some deep-sea fish, like lanternfish and marine hatchetfish, are sometimes called pseudoceanic. This is because they are found in much larger numbers around underwater mountains (seamounts) and over continental slopes. This happens because their prey also gather around these structures.

Fish in different deep-sea zones look and act very differently. Groups of species living together in each zone seem to have similar ways of life. For example, small fish that swim up and down daily in the twilight zone, or the anglerfishes in the midnight zone.

Fish with spiny fins are rare in the deep sea. This suggests that deep-sea fish are very old species. They are so well-suited to their environment that newer types of fish haven't been able to take over. Most deep-sea pelagic fish belong to their own special groups. This shows they have evolved in the deep sea for a very long time.

Many species move daily between zones. They swim up and down in what are called vertical migrations.

| Zone | Examples of Fish |

|---|---|

| Epipelagic (Sunlit) |

|

| Mesopelagic (Twilight) | Lanternfish, opah, longnose lancetfish, barreleye, ridgehead, sabretooth, stoplight loosejaw, marine hatchetfish |

| Bathypelagic (Midnight) | Mainly bristlemouth and anglerfish. Also fangtooth, viperfish, black swallower, telescopefish, hammerjaw, daggertooth, barracudina, black scabbardfish, bobtail snipe eel, unicorn crestfish, gulper eel, flabby whalefish. |

| Benthopelagic (Near-Bottom) | Rattail and brotula are very common. |

| Benthic (On Bottom) | Flatfish, hagfish, eelpout, greeneye eel, stingray, lumpfish, and batfish |

| Feature | Epipelagic (Sunlit) | Mesopelagic (Twilight) | Bathypelagic (Midnight) | Deep Sea Bottom |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscles | Strong | Muscular bodies | Weak, soft | Strong |

| Skeleton | Strong | Strong, bony | Weak, not very bony | Strong |

| Scales | Yes | Yes | None | Variable (yes or no) |

| Nervous System | Well developed | Well developed | Only side-line and smell | Well developed |

| Eyes | Large | Large and sensitive | Small, may not work | Variable (good to none) |

| Light Organs (Photophores) | Absent | Common | Common | Usually absent |

| Gills | Well developed | Well developed | Small | Well developed |

| Kidneys | Large | Large | Small | Well developed |

| Heart | Large | Large | Small | Well developed |

| Swimbladder | Yes | Migratory fish have them | Small or gone | Variable (good to none) |

| Size | Variable | Variable | Usually under 25 cm | Variable, over one meter is common |

Twilight Zone Fish (Mesopelagic Fish)

Below the sunlit zone, things change fast. Between 200 and about 1000 meters, the light gets dimmer until it's almost completely dark. This is the twilight or mesopelagic zone. Temperatures drop to between 4°C and 8°C. The pressure also increases a lot, getting stronger by one atmosphere every 10 meters. Food and oxygen levels are low.

During World War II, sonar operators were confused by what looked like a false seafloor. It was 300–500 meters deep during the day and shallower at night. This turned out to be millions of tiny marine animals, especially small mesopelagic fish. Their swimbladders reflected the sonar. These animals swim up to shallower water at dusk to eat tiny plankton. This event is known as the deep scattering layer.

Most mesopelagic fish make daily vertical migrations. They move up to the sunlit zone at night, often following the tiny animals they eat. They return to the deep for safety during the day. These migrations cover long distances up and down. They use a swimbladder to help them. Inflating the swimbladder to go up takes a lot of energy because of the high pressure. When they go down, they deflate it. Some mesopelagic fish swim through big temperature changes, showing they can handle it.

These fish have strong muscles, bony skeletons, scales, and good gills and nervous systems. They also have large hearts and kidneys. Mesopelagic fish that filter feed have small mouths with fine gill rakers. Fish that eat other fish have larger mouths and coarser gill rakers. Fish that migrate up and down have swimbladders.

Mesopelagic fish are built for active lives in low light. Most are visual predators with big eyes. Some deeper-water fish have special tube-shaped eyes that point upward. These eyes are very sensitive to small light signals. This helps them spot squid, cuttlefish, and smaller fish silhouetted against the dim light above.

Mesopelagic fish usually don't have sharp spines for defense. They use color to camouflage themselves. Fish that hide and wait for prey are dark, black, or red. Since red light doesn't reach the deep sea, red looks like black down there. Fish that migrate up and down have silvery colors to hide. On their bellies, they often have photophores, which are light-producing organs. These lights help them hide their shape from predators looking up from below. However, some predators have yellow lenses in their eyes. These lenses filter out the blue light, making the bioluminescence visible.

-

The Antarctic toothfish has large, upward-looking eyes to spot prey.

-

The stoplight loosejaw is one of the few fish that makes red bioluminescence. This lets it hunt with a light beam that most prey can't see.

The brownsnout spookfish is the only known animal with eyes that use a mirror, not a lens, to focus images.

Studies show that lanternfish make up about 65% of all deep-sea fish. Lanternfish are among the most widespread and diverse animals with backbones. They are very important as food for larger animals. The total weight of lanternfish in the world is estimated to be 550–660 million metric tonnes. This is several times more than all the fish caught by fisheries worldwide. Lanternfish are also a big part of the deep scattering layer in the oceans. Sonar bounces off their millions of swimbladders, making it look like a false bottom.

Bigeye tuna are fish that live in both the sunlit and twilight zones. They eat other fish. Satellite tracking has shown that bigeye tuna often swim deep below the surface during the day. They sometimes dive as deep as 500 meters. These movements are likely because they are following the prey that migrate up and down in the deep scattering layer.

-

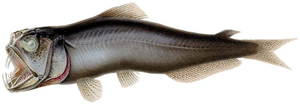

Longnose lancetfish are ambush predators that live in the twilight zone. They are among the largest fish in this zone (up to 2 meters).

-

Bigeye tuna swim in the sunlit zone at night and the twilight zone during the day.

-

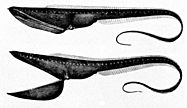

A group of twilight zone forage fish caught in the Gulf of Mexico. It includes Myctophids, young anglerfishes, bristlemouths, and a barracudina.

Midnight Zone Fish (Bathypelagic Fish)

Below the twilight zone, it is completely dark. This is the midnight or bathypelagic zone. It stretches from 1000 meters down to the very deep ocean floor. If the water is super deep, the zone below 4000 meters is sometimes called the lower midnight or abyssopelagic zone.

Conditions are pretty much the same throughout these zones: total darkness, crushing pressure, and very low temperatures, nutrients, and oxygen.

Bathypelagic fish have special ways to deal with these conditions. They have slow metabolisms and eat whatever they can find. They prefer to wait for food rather than waste energy searching. Unlike twilight zone fish, which are often very active, midnight zone fish are almost all "sit-and-wait" predators. They move very little.

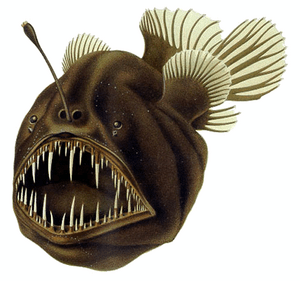

The main fish in the midnight zone are small bristlemouth and anglerfish. Fangtooth, viperfish, daggertooth, and barracudina are also common. These fish are small, many around 10 centimeters long, and few are longer than 25 cm. They spend most of their time patiently waiting for prey to appear or be drawn in by their glowing lights. The little energy available in the midnight zone comes from bits of dead material, waste, and occasional small animals or twilight zone fish falling from above. Only about 5% of the food from the sunlit zone makes it down to the midnight zone.

Bathypelagic fish are still. They are built to use very little energy in a place with almost no food or energy, except for their own light. Their bodies are long with weak, watery muscles and skeletons. Since they are mostly water, the huge pressure doesn't crush them. They often have mouths that can stretch wide, with hinged jaws and curved teeth. They are slimy and have no scales. Their main senses are their side-line system (which feels water pressure changes) and their sense of smell. Their eyes are small and may not work. Gills, kidneys, hearts, and swimbladders are small or missing.

These features are similar to those of young fish larvae. This suggests that over time, bathypelagic fish have kept these features from their young stages. Like larvae, these features help the fish stay floating in the water with little effort.

Even though they look scary, these deep-sea creatures are mostly small fish with weak muscles. They are too small to be a threat to humans.

Deep-sea fish either don't have swimbladders or they don't work well. Midnight zone fish usually don't swim up and down. Filling a swimbladder at such high pressures would cost too much energy. Some deep-sea fish have swimbladders when they are young and live in the upper ocean. But these shrivel or fill with fat when the fish move to their adult deep-sea homes.

Their most important senses are usually their inner ear (for sound) and their lateral line (for feeling water pressure changes). Smell can also be important for males to find females.

Bathypelagic fish are black, or sometimes red. They have few light-producing organs. When they do use lights, it's usually to attract prey or a mate. Because food is so rare, midnight zone predators are not picky eaters. They grab whatever comes close enough. They do this with large mouths and sharp teeth for big prey. They also have overlapping gill rakers that stop small prey from escaping once swallowed.

Finding a mate in this zone is hard. Some species use bioluminescence to attract each other. Others are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female parts. This doubles their chances of making eggs and sperm when they meet. Female anglerfish release chemicals to attract tiny males. When a male finds her, he bites onto her and never lets go. In some anglerfish species, the male's skin and the female's body even fuse together. The male then shrinks down to just a pair of reproductive organs. This extreme difference between male and female ensures that when the female is ready to lay eggs, she has a mate right there.

Many other animals besides fish live in the midnight zone, like squid, whales, octopuses, and sea stars. But this zone is a very tough place for fish to live.

-

The black swallower can swallow whole bony fish that are ten times its own weight because its stomach can stretch.

-

The Sloane's viperfish can swim up from the midnight zone to near the surface every night.

Fish Near the Bottom (Demersal Fish)

Demersal fish live on or near the bottom of the sea. They are found on the seafloor in coastal areas above the continental shelf. In the open ocean, they live along the outer edge of the continental margin, on the continental slope and rise. They are not usually found in the very deepest parts of the ocean or on flat abyssal plains. They live on different types of seafloors, like mud, sand, gravel, or rocks.

In deep waters, fish in the demersal zone are active and quite common. This is especially true compared to fish in the midnight zone.

Rattails and brotulas are common. Other well-known families include eels, eelpouts, hagfishes, greeneyes, batfishes, and lumpfishes.

Deep-water bottom-dwelling fish have strong muscles and well-developed organs. In this way, they are more like twilight zone fish than midnight zone fish. They vary more in other ways. Light organs are usually missing. Eyes and swimbladders can be anywhere from missing to very well developed. They also vary in size, with larger species over one meter long being common.

Deep-sea bottom fish are usually long and thin. Many are eels or shaped like eels. This might be because long bodies have long side-line systems. Side-line systems detect low-frequency sounds. Some bottom fish seem to have muscles that make these sounds to attract mates. Smell is also important. This is shown by how quickly bottom fish find traps baited with other fish.

The main food for deep-sea bottom fish is tiny animals from the deep-sea bottom and dead animals. Smell, touch, and side-line senses seem to be the main ways they find food.

Deep-sea bottom fish can be split into strictly bottom fish and near-bottom fish. Strictly bottom fish usually sink, while near-bottom fish float neutrally. Strictly bottom fish stay in constant contact with the bottom. They either lie and wait as predators or actively move over the bottom looking for food.

Fish Just Above the Bottom (Benthopelagic Fish)

Benthopelagic fish live in the water just above the bottom. They eat tiny animals from the bottom and near-bottom water. Most fish that live near the bottom are benthopelagic.

They can be divided into soft-bodied or strong-bodied types. Soft-bodied benthopelagic fish are like midnight zone fish. They have less body mass and slow body processes. They use very little energy as they lie and wait to ambush prey. An example is the cusk-eel Acanthonus armatus. This predator has a huge head and a body that is 90% water. This fish has the largest ears and the smallest brain compared to its body size of all known animals with backbones.

Strong-bodied benthopelagic fish are muscular swimmers. They actively cruise the bottom looking for prey. They might live around features like seamounts, where there are strong currents. Examples are the orange roughy and Patagonian toothfish. These fish were once very common. Because their strong bodies are good to eat, they have been caught a lot by fishermen.

Fish Directly on the Bottom (Benthic Fish)

Benthic fish are not pelagic fish, but they are mentioned here to give a full picture.

Some fish don't fit perfectly into these groups. For example, the family of almost blind spiderfishes are common and widespread. They eat tiny animals that float near the bottom. Yet, they are strictly bottom fish. They stay in contact with the bottom. Their fins have long rays that they use to "stand" on the bottom. They face the current and grab tiny animals as they float by.

The deepest-living fish known is the strictly bottom-dwelling Abyssobrotula galatheae. It looks like an eel, is blind, and eats tiny animals on the bottom.

-

The tripodfish (Bathypterois grallator), a type of spiderfish, uses its long fin extensions to "stand" on the bottom.

-

The blotched fantail ray eats bottom-dwelling fish, clams, crabs, and shrimp.

At very deep levels, little food and extreme pressure limit how well fish can survive. The deepest point of the ocean is about 11,000 meters. Midnight zone fish are not usually found below 3,000 meters. The deepest a bottom fish has been recorded is 8,370 meters. It might be that extreme pressures stop important body processes from working.

Bottom fish are more varied and are often found on the continental slope. This area has many different habitats and often good food supplies. About 40% of the ocean floor is flat abyssal plains. But these flat, featureless areas are covered with mud and have little bottom life. Deep-sea bottom fish are more likely to live near canyons or rocky areas among the plains. Here, communities of tiny animals live. Underwater mountains (seamounts) can block deep-sea currents. This causes nutrient-rich water to rise, which supports bottom fish. Underwater mountain ranges can also divide underwater regions into different ecosystems.

Fishing for Pelagic Fish

Forage Fish (Small Pelagic Fish)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Small pelagic fish are usually forage fish. This means they are hunted by larger pelagic fish and other predators. Forage fish filter feed on plankton and are usually less than 10 centimeters long. They often stay together in schools. They might also migrate long distances between where they lay eggs and where they feed. They are found especially in areas where deep, nutrient-rich water rises to the surface. These areas include the northeast Atlantic, off Japan, and off the west coasts of Africa and the Americas. Forage fish usually don't live very long. Their numbers can change a lot from year to year.

Herring are found in the North Sea and the North Atlantic. They live at depths up to 200 meters. Important herring fisheries have been in these areas for hundreds of years. Herring of different sizes and growth rates belong to different groups. Each group has its own migration paths. When laying eggs, a female produces 20,000 to 50,000 eggs. After laying eggs, the herring are low on fat. They then migrate back to feeding areas rich in plankton. Around Iceland, three separate groups of herring were traditionally fished. These groups almost disappeared in the late 1960s. Two of them have since recovered. After the collapse, Iceland started fishing for capelin. Now, capelin make up about half of Iceland's total fish catch.

Blue whiting are found in the open ocean and above the continental slope. They live at depths between 100 and 1000 meters. They follow the tiny animals they eat. They swim down to the bottom during the day and up to the surface at night.

Traditional fisheries for anchovies and sardines have also operated in the Pacific, the Mediterranean, and the southeast Atlantic. The world's yearly catch of forage fish has been around 22 million tonnes in recent years. This is about a quarter of the world's total fish catch.

-

These schooling Pacific sardines are forage fish.

-

Herring eating tiny copepods by swimming with their mouths open.

Predator Fish (Larger Pelagic Fish)

Medium-sized pelagic fish include trevally, barracuda, flying fish, bonito, mahi mahi, and coastal mackerel. Many of these fish hunt forage fish. But they, in turn, are hunted by even larger pelagic fish. Nearly all fish are predators to some extent. So, the difference between predator fish and prey fish is not always clear.

Around Europe, there are three groups of coastal mackerel. One group migrates to the North Sea. Another stays in the waters of the Irish Sea. The third group migrates south along the west coast of Scotland and Ireland. Mackerel can swim at an impressive speed of 10 kilometers per hour.

Many large pelagic fish are ocean travelers. They make long migrations far from shore. They eat small pelagic forage fish, as well as medium-sized pelagic fish. Sometimes, they follow their schooling prey. Many of these larger species also form schools themselves.

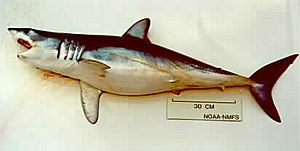

Examples of larger pelagic fish are tuna, billfish, king mackerel, sharks, and large rays.

Tuna are especially important for commercial fishing. Although tuna migrate across oceans, fishermen don't usually just look for them anywhere. Tuna tend to gather in areas where food is plentiful. These areas include the edges of currents, around islands, near underwater mountains, and in some areas where deep, nutrient-rich water rises. Tuna are caught in several ways:

- Large fishing boats use huge nets to surround entire schools of tuna swimming near the surface.

- Other boats use poles with bait fish to catch them.

- Fishermen also set up rafts called fish aggregating devices (FADs). Tuna and some other pelagic fish tend to gather under floating objects.

Other large pelagic fish are popular for sport fishing, especially marlin and swordfish.

-

Yellowfin tuna are being caught more as a replacement for the now very low numbers of Southern bluefin tuna.

-

King mackerel swim on long migrations at 10 kilometers per hour.

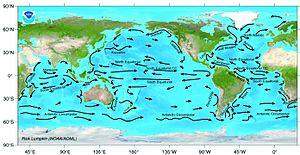

Ocean Productivity

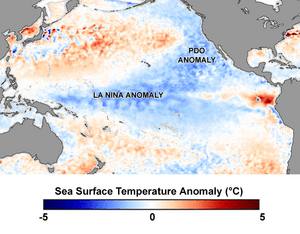

Upwelling happens both along coastlines and in the middle of the ocean. It occurs when deep ocean currents bring cold water, rich in nutrients, to the surface. These upwellings cause tiny plants (phytoplankton) to grow a lot. This, in turn, produces tiny animals (zooplankton) and supports many of the world's main fisheries. If the upwelling stops, then the fisheries in that area will fail.

In the 1960s, the Peruvian anchoveta fishery was the largest in the world. The anchoveta population dropped greatly during the 1972 El Niño event. This happened when warm water flowed over the cold Humboldt Current. The upwelling stopped, and the production of tiny plants dropped sharply. So did the anchoveta population. Millions of seabirds, which depended on the anchoveta, died. Since the mid-1980s, the upwelling has returned. The Peruvian anchoveta catch levels are now back to what they were in the 1960s.

Off Japan, two currents meet: the cold Oyashio Current and the warm Kuroshio Current. This meeting creates nutrient-rich upwellings. Changes in these currents caused the sardine populations to decline. Fish catches fell from 5 million tonnes in 1988 to 280 thousand tonnes in 1998. As a result, Pacific bluefin tuna stopped coming to the region to feed.

Ocean currents can affect where fish are found. They can gather fish together or spread them out. Nearby ocean currents can create clear, though changing, boundaries. These boundaries can even be seen. But usually, you know they are there by quick changes in saltiness, temperature, and how cloudy the water is.

For example, in the Asian northern Pacific, albacore tuna are found between two current systems. The cold North Pacific Current forms the northern boundary. The North Equatorial Current forms the southern boundary. To make it more complex, another current, the Kuroshio Current, changes their distribution within this area. Its flows change with the seasons.

Epipelagic fish often lay their eggs in an area where the eggs and young fish will drift downstream. They float into good feeding areas. Eventually, they drift into the adult feeding areas.

Islands and underwater banks can interact with currents and upwellings. This creates areas where the ocean is very productive. Large swirling currents can form downwind or downcurrent from islands, gathering tiny plankton. Banks and reefs can block deep currents, causing upwellings.

Fish That Travel Far (Highly Migratory Species)

Epipelagic fish generally travel long distances between their feeding and spawning areas. They also move in response to changes in the ocean. Large ocean predators, like salmon and tuna, can migrate thousands of kilometers, crossing entire oceans.

In a 2001 study, scientists tracked Atlantic bluefin tuna from North Carolina. They used special tags that popped up after about a year. These tags floated to the surface and sent their information to a satellite. The study found that the tuna had four different migration patterns. One group stayed in the western Atlantic for a year. Another group also stayed mainly in the western Atlantic but migrated to the Gulf of Mexico to lay eggs. A third group crossed the Atlantic Ocean and came back. The fourth group crossed to the eastern Atlantic and then moved into the Mediterranean Sea to lay eggs. The study showed that there is essentially only one population of Atlantic bluefin tuna. Different groups within this population use all of the North Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Mediterranean Sea.

The term highly migratory species (HMS) is a legal term. It comes from an international agreement called the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Highly migratory species include:

- tuna and tuna-like species (like albacore, Atlantic bluefin, bigeye tuna, skipjack, yellowfin, blackfin, little tunny, Pacific bluefin, southern bluefin and bullet)

- pomfret

- marlin

- sailfish

- swordfish

- saury

- Ocean-going sharks

- Mammals like dolphins and other whales.

Basically, highly migratory species are the larger "large pelagic fish." They are high up on the food chain. They travel long, but varying, distances across oceans to feed (often on forage fish) or to reproduce. They are also found in many different places. So, these species are found both inside countries' 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zones and in the high seas outside these zones. They are pelagic species. This means they mostly live in the open ocean and not near the seafloor. However, they might spend part of their lives in waters near the shore.

Fish Catch Numbers

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the world caught 93.2 million tonnes of fish in 2005. This was from commercial fishing in the wild. About 45% of this total was pelagic fish. The table below shows the world's fish catch in tonnes.

| Fish Caught by Groups (in tonnes) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Group | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

| Small Pelagic Fish | Herrings, sardines, anchovies | 22,671,427 | 24,919,239 | 20,640,734 | 22,289,332 | 18,840,389 | 23,047,541 | 22,404,769 |

| Large Pelagic Fish | Tunas, bonitos, billfishes | 5,943,593 | 5,816,647 | 5,782,841 | 6,138,999 | 6,197,087 | 6,160,868 | 6,243,122 |

| Other Pelagic Fish | 10,712,994 | 10,654,041 | 12,332,170 | 11,772,320 | 11,525,390 | 11,181,871 | 11,179,641 | |

| Cartilaginous Fish | Sharks, rays, chimaeras | 858,007 | 870,455 | 845,854 | 845,820 | 880,785 | 819,012 | 771,105 |

Threatened Species

In 2009, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) made the first list of threatened open-ocean sharks and rays. They said that about one-third of these sharks and rays are in danger of extinction. There are 64 species of oceanic sharks and rays on this list. These include hammerheads, giant devil rays, and porbeagle sharks.

Oceanic sharks are often caught by accident by swordfish and tuna fisheries in the high seas. In the past, there wasn't much demand for sharks. They were seen as worthless fish caught by mistake. Now, sharks are being hunted more and more to supply markets in Asia, especially for shark fins. These are used in shark fin soup.

Shark populations in the northwest Atlantic Ocean are estimated to have dropped by 50% since the early 1970s. Oceanic sharks are vulnerable because they don't have many young. Also, their young can take decades to grow up.

-

The scalloped hammerhead shark is classified as endangered.

-

The oceanic whitetip shark has declined by 99% in the Gulf of Mexico.

-

The devil fish, a large ray, is threatened.

-

The porbeagle shark is threatened.

In some parts of the world, the scalloped hammerhead shark has declined by 99% since the late 1970s. It is listed as globally endangered, meaning it is close to extinction.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |