Events leading to the attack on Pearl Harbor facts for kids

A series of important events led up to the attack on Pearl Harbor. For many years, both Japan and the United States thought war between them might happen. Their militaries even planned for it in the 1920s. The U.S. gaining more land in the Pacific Ocean had worried Japan since the 1890s. But the real problems started when Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931.

Japan worried about being taken over by other countries. So, its government decided to expand its own power in Asia and the Pacific. They wanted to become a "Great Power" like the Western nations. Japan believed that to be modern, it needed to be a colonial power. Also, some unfair laws in Western countries made Japanese people feel angry. These laws stopped Japanese (and often Chinese) people from becoming citizens, owning land, or moving to these countries.

Over the next ten years, Japan slowly expanded into China. This led to the Second Sino-Japanese war in 1937. In 1940, Japan invaded French Indochina. They did this to stop supplies, including war materials from the U.S., from reaching China. This action made the United States stop all oil exports to Japan. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) then realized they had less than two years of oil left. This pushed them to seize oil resources in the Dutch East Indies. Japan had already been planning to take over this "Southern Resource Area" to create its vision of a "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" in the Pacific.

The Philippines, which was an American protectorate at the time, was also a target for Japan. The Japanese military thought invading the Philippines would make the U.S. fight back. Instead of taking the islands and waiting for a U.S. counterattack, Japan's military leaders decided on a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. They believed this attack would stop the American forces from being able to free the Philippines. (Later that same day, December 8 local time, Japan did invade the Philippines).

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto began planning the attack on Pearl Harbor in early 1941. He finally convinced the Naval High Command to agree, partly by threatening to resign. The attack was approved at two important meetings called Imperial Conferences. Throughout the year, pilots were trained, and ships were made ready. The attack was given final approval if Japan could not reach a good diplomatic agreement. After the Hull note and final approval from Emperor Hirohito, the order to attack was given in early December.

Contents

Why Japan and the U.S. Had Problems

Both the Japanese public and their leaders started to see the U.S. as an enemy in the 1890s. The U.S. took over Pacific islands close to Japan. Also, the U.S. helped end the Russo-Japanese War with the Treaty of Portsmouth. This treaty didn't make either side, especially Japan, happy. This made Japan feel that the U.S. was getting too involved in Asian politics and trying to limit Japan's power. This set the stage for bigger problems later on.

Problems between Japan and powerful Western countries (like the U.S., France, Britain, and the Netherlands) grew a lot during the early reign of Emperor Hirohito. Japanese nationalists and military leaders had more and more say in government. They promoted the idea of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. This was part of Japan's belief in its ""divine right"" to unite Asia under Hirohito's rule.

In the 1930s, Japan's expanding policies led to new fights with its neighbors, Russia and China. (Japan had fought China in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95 and Russia in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–05. Japan's desire for more land caused both conflicts). In March 1933, Japan left the League of Nations. This was because other countries criticized Japan for taking over Manchuria and setting up a puppet government there. On January 15, 1936, Japan also left the Second London Naval Disarmament Conference. This happened because the U.S. and the United Kingdom would not let the Japanese Navy be as strong as theirs. A second war between Japan and China began in July 1937 with the Marco Polo Bridge Incident.

The U.S. and several members of the League of Nations, including Britain, France, Australia, and the Netherlands, spoke out against Japan's 1937 attack on China. Japanese cruelties during the war, like the terrible Nanking Massacre that December, made relations with the rest of the world even worse. The U.S., Britain, France, and the Netherlands all had colonies in East and Southeast Asia. Japan's new military strength and willingness to use it threatened these Western countries' economic and land interests in Asia.

Starting in 1938, the U.S. began to limit trade with Japan more and more. They ended their 1911 trade agreement with Japan in 1939. This was made even stricter by the Export Control Act of 1940. But these efforts did not stop Japan from continuing its war in China. Japan also signed the Tripartite Pact in 1940 with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, officially forming the Axis Powers.

Japan planned to use Hitler's war in Europe to help its own goals in the Far East. The Tripartite Pact promised help if a country was attacked by any nation not already fighting them. This secretly meant the U.S. By joining the pact, Japan gained power. It also sent a clear message that any U.S. military action risked war on both sides of America: with Germany and Italy in the Atlantic, and with Japan in the Pacific. But the Roosevelt administration was not swayed. It promised to help the British and Chinese with money and supplies. This aid was meant to ensure they could survive. So, the U.S. slowly changed from a neutral country to one getting ready for war.

In mid-1940, President Roosevelt moved the U.S. Pacific Fleet to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. This was meant to discourage Japan. On October 8, 1940, Admiral James O. Richardson, the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, argued with Roosevelt. He repeated his earlier points to Admiral Harold R. Stark and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox. Richardson believed Pearl Harbor was the wrong place for his ships. Roosevelt thought moving the fleet to Hawaii would have a "restraining influence" on Japan.

Richardson asked the President if the U.S. was going to war. Roosevelt's view was that by October 8, 1940, the U.S. would likely get involved in a war with Japan. He said that if Japan attacked Thailand, the Kra Peninsula, or the Dutch East Indies, the U.S. would not enter the war. He even doubted if they would enter if Japan attacked the Philippines. But he believed that Japan would eventually make a mistake as the war continued and expanded, and then the U.S. would join the war.

Japan's move into Vichy-controlled French Indochina in 1940 made tensions even higher. Along with Japan's war with China, leaving the League of Nations, joining Germany and Italy, and growing military, this made the U.S. increase its economic pressure on Japan. The U.S. stopped shipping scrap metal to Japan. It also closed the Panama Canal to Japanese ships. This hurt Japan's economy a lot because 74.1% of Japan's scrap iron came from the U.S. in 1938. Also, 93% of Japan's copper in 1939 came from the U.S. In early 1941, Japan moved into southern Indochina. This threatened British Malaya, North Borneo, and Brunei.

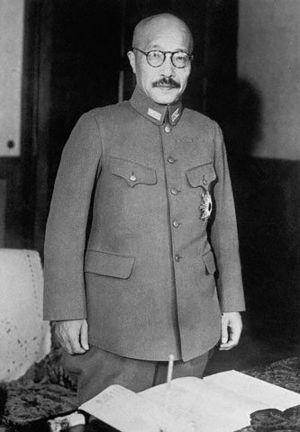

Japan and the U.S. talked throughout 1941 to try and improve their relationship. During these talks, Japan thought about leaving most of China and Indochina after making peace with the Chinese. Japan would also interpret the Tripartite Pact independently. They would not discriminate in trade if other countries did the same. However, General Tojo, who was Japan's War Minister, refused to compromise on China. After Japan took over key airfields in Indochina (July 24) following a deal with Vichy France, the U.S. froze Japanese assets on July 26, 1941. On August 1, they stopped all oil and gasoline exports to Japan. The oil embargo was a very strong move. Oil was Japan's most important import, and over 80% of Japan's oil came from the U.S. at that time.

Japanese war planners had long looked south, especially to Brunei for oil and Malaya for rubber and tin. In late 1940, Japan asked for 3.15 million barrels of oil from the Dutch East Indies. But they were only offered 1.35 million. The complete U.S. oil embargo left Japan with two choices. They could either seize Southeast Asia before their current supplies ran out, or give in to American demands. Also, any operation in the south would be open to attack from the Philippines, which was a U.S. territory. So, war with the U.S. seemed necessary anyway.

After the embargoes and asset freezes, the Japanese ambassador to Washington, Kichisaburō Nomura, and U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull had many meetings. They tried to fix Japanese-American relations. But no solution could be found for three main reasons:

- Japan honored its alliance with Germany and Italy through the Tripartite Pact.

- Japan wanted economic control and responsibility for Southeast Asia (as planned in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere).

- Japan refused to leave mainland China (except for its puppet state of Manchukuo).

In their final offer on November 20, Japan suggested pulling its forces out of southern Indochina. They also promised not to attack anywhere else in Southeast Asia. In return, the U.S., Britain, and the Netherlands had to stop helping China and lift their sanctions against Japan. The American counter-offer on November 26 (the Hull note) demanded that Japan leave all of China, without conditions. It also asked them to sign non-aggression agreements with other Pacific powers.

Ending the Talks

Part of Japan's plan for the attack was to end talks with the U.S. 30 minutes before the attack began. Japanese diplomats in Washington, including Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura and special representative Saburō Kurusu, had been talking with the State Department. They were discussing the U.S. reaction to Japan's move into French Indochina that summer.

In the days before the attack, a long 14-part message was sent to the embassy from Tokyo. This message was encrypted using a special code called PURPLE by U.S. codebreakers. The instructions were to deliver it to Secretary of State Cordell Hull at 1:00 PM Washington time on December 7, 1941. The last part arrived late Saturday night (Washington time). But because of delays in decoding and typing, and because Tokyo didn't stress how important the timing was, embassy staff didn't give the message to Secretary Hull until several hours after the attack.

The U.S. had decoded the 14th part before the Japanese embassy did. They had it long before the embassy staff typed a clean copy. The final part, with its delivery time, was decoded Saturday night. But it wasn't acted upon until the next morning.

Ambassador Nomura asked to see Hull at 1:00 PM. But he later asked to postpone it to 1:45 PM because he wasn't ready. Nomura and Kurusu arrived at 2:05 PM and met Hull at 2:20 PM. Nomura apologized for the delay. After Hull read several pages, he asked Nomura if the document was from the Japanese government. The Ambassador said yes. After reading the whole document, Hull told the ambassador: "I must say that in all my conversations with you...during the last nine months I have never uttered one word of untruth. This is borne out absolutely by the record. In all my fifty years of public service I have never seen a document that was more crowded with infamous falsehoods and distortions--infamous falsehoods and distortions on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any Government on this planet was capable of uttering them."

Japanese records, shown in hearings after the war, proved that Japan had not even written a declaration of war until they heard the attack was successful. The short two-line declaration was finally given to U.S. ambassador Joseph Grew in Tokyo about ten hours after the attack ended. Grew was allowed to send it to the U.S., where it was received late Monday afternoon (Washington time).

The Decision for War

In July 1941, the IJN headquarters told Emperor Hirohito that their oil reserves would run out in two years if they didn't find a new source. In August 1941, Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe suggested a meeting with President Roosevelt to talk about their disagreements. Roosevelt replied that Japan must leave China before such a meeting could happen. On September 6, 1941, at the second Imperial Conference, Japanese leaders met to discuss attack plans. These plans were for attacks on Western colonies in Asia and Hawaii. This meeting happened one day after the emperor had criticized General Hajime Sugiyama, chief of the IJA General Staff. He was unhappy about the lack of success in China and the low chances of winning against the U.S., the British Empire, and their allies.

Prime Minister Konoe argued for more talks and possible compromises to avoid war. However, military leaders like Sugiyama, Minister of War General Hideki Tōjō, and chief of the IJN General Staff Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano said time had run out. They believed more talks would be useless. They pushed for quick military actions against all American and European colonies in Southeast Asia and Hawaii. Tōjō argued that giving in to the American demand to pull troops out of China would erase all the gains from the Second Sino-Japanese War. It would also lower army morale, endanger Manchukuo, and risk control of Korea. So, doing nothing was like a defeat and a loss of face.

On October 16, 1941, Konoe resigned. He suggested Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni as his replacement, who was also the army and navy's choice. Hirohito chose Hideki Tōjō instead. He worried, as he told Konoe, about the Imperial Family being blamed for a war against Western powers.

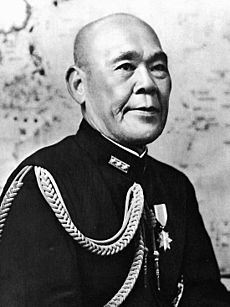

On November 3, 1941, Nagano showed Hirohito a complete plan for the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the Imperial Conference on November 5, Hirohito approved the plan for war against the U.S., Great Britain, and the Netherlands. It was set to start in early December if a good diplomatic solution wasn't found by then. In the following weeks, Tōjō's military government offered a final deal to the U.S. They offered to leave only Indochina, but in return for a lot of American economic aid. On November 26, the Hull note rejected this offer. It demanded that Japan not only leave Indochina but also China (without Manchoukuo). They also had to agree to an Open Door Policy in the Far East.

On November 30, 1941, Prince Takamatsu warned his brother, Hirohito. He said the navy felt Japan could not fight the U.S. for more than two years and wanted to avoid war. After talking with Kōichi Kido (who told him to take his time until he was sure) and Tōjō, the Emperor called Shigetarō Shimada and Nagano. They told him that war would be successful. On December 1, Hirohito finally approved a "war against United States, Great Britain and Holland" at another Imperial Conference. It would begin with a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at its main base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

Gathering Information

On February 3, 1940, Yamamoto told Captain Kanji Ogawa of Naval Intelligence about the possible attack plan. He asked him to start gathering information on Pearl Harbor. Ogawa already had spies in Hawaii, including Japanese Consular officials. He also got help from a German agent living in Hawaii. None of them had been giving much useful military information. He planned to add 29-year-old Ensign Takeo Yoshikawa. By spring 1941, Yamamoto officially asked for more Hawaiian intelligence. Yoshikawa boarded a ship called Nitta-maru in Yokohama. He grew his hair longer than military style and pretended to be Tadashi Morimura.

Yoshikawa started gathering information seriously. He took car trips around the main islands and flew over Oahu in a small plane, pretending to be a tourist. He visited Pearl Harbor often. He sketched the harbor and where ships were from the top of a hill. Once, he got into Hickam Field in a taxi. He memorized the number of planes, pilots, hangars, barracks, and soldiers he saw. He also found out that Sunday was the day with the most ships in the harbor. He learned that PBY patrol planes flew out every morning and evening. And he discovered there was an anti-submarine net at the harbor's entrance. This information was sent back to Japan in coded messages from the Consulate. It was also given directly to intelligence officers on Japanese ships visiting Hawaii.

In June 1941, German and Italian consulates were closed. There were suggestions that Japan's should be closed too. But they weren't, because they kept providing valuable information (through MAGIC, which was the U.S. codebreaking operation). Neither President Franklin D. Roosevelt nor Secretary of State Cordell Hull wanted trouble in the Pacific. If they had been closed, the Naval General Staff, who had been against the attack from the start, might have called it off. This is because up-to-date information on the Pacific Fleet's location, which Yamamoto's plan needed, would no longer be available.

Planning the Attack

Japan expected war. Seeing a chance with the U.S. Pacific Fleet based in Hawaii, the Japanese began planning an attack on Pearl Harbor in early 1941. For several months, the Japanese Navy spent a lot of time planning and organizing a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. They also planned to invade British and Dutch colonies to the south at the same time. The plans for Pearl Harbor came from Japan's belief that the U.S. would surely join the war after a Japanese attack on Malaya and Singapore.

The goal of a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor was to disable American naval power in the Pacific. This would stop it from interfering with operations against American, British, and Dutch colonies. Successful attacks on these colonies depended on dealing with the Pacific Fleet first. Planners had long expected a battle in Japanese waters after the U.S. fleet traveled across the Pacific. They thought the U.S. fleet would be attacked by submarines and other forces along the way. Then, it would be defeated in a "decisive battle", like Russia's Baltic Fleet was in 1905. A surprise attack had two main problems compared to these old plans. First, the Pacific Fleet was very strong and would be hard to defeat or surprise. Second, Pearl Harbor's shallow waters made regular aerial torpedoes useless. On the other hand, Hawaii's distance meant a successful surprise attack could not be stopped or quickly fought back by forces from the U.S. mainland.

Several Japanese naval officers were impressed by the British action in the Battle of Taranto. In that battle, 21 old planes disabled half of the Italian Navy. Admiral Yamamoto even sent a group to Italy. They concluded that a bigger, better-supported version of that attack could force the U.S. Pacific Fleet to retreat to bases in California. This would give Japan the time needed to set up defenses to protect its control of the Dutch East Indies. The group returned to Japan with information about the shallow-running torpedoes the British engineers had created.

Japanese planners were also influenced by Admiral Togo's surprise attack on the Russian Pacific Fleet at Port Arthur in 1904. Yamamoto wanted to destroy the American battleships. This was in line with the ideas of Mahan, which were followed by all major navies at the time, including the U.S. Navy and Royal Navy.

In a letter dated January 7, 1941, Yamamoto finally sent a rough plan to Koshiro Oikawa, who was the Navy Minister. He also asked to be made Commander in Chief of the air fleet for the Pearl Harbor attack. A few weeks later, in another letter, Yamamoto asked Admiral Takijiro Onishi, chief of staff of the Eleventh Air Fleet, to study if an attack on the American base was technically possible. Onishi gathered as many facts as he could about Pearl Harbor.

After talking to Kosei Maeda, an expert on aerial torpedoes, who said the harbor's shallow waters made such an attack almost impossible, Onishi called Commander Minoru Genda. After studying Yamamoto's original idea, Genda agreed: "The plan is difficult but not impossible." Yamamoto gave most of the planning to Rear Admiral Ryunosuke Kusaka. Kusaka was very worried about the air defenses in the area. Yamamoto encouraged Kusaka by telling him, "Pearl Harbor is my idea and I need your support." Genda stressed that the attack should happen early in the morning and be a complete surprise. It would use an aircraft carrier group and different types of bombing.

Attacking the U.S. Pacific Fleet at its anchorage would achieve surprise. But it also had two clear downsides. The ships would sink or be damaged in very shallow water. This meant they could likely be salvaged and possibly returned to duty (which six of the eight battleships eventually were). Also, most of the crews would survive the attack. Many would be on shore leave or could be rescued from the harbor afterward. Despite these worries, Yamamoto and Genda pushed forward.

By April 1941, the Pearl Harbor plan was called Operation Z. This name came from the famous Z signal given by Admiral Togo at Tsushima. Over the summer, pilots trained seriously near Kagoshima City on Kyūshū. Genda chose this location because its land and buildings were similar to the problems bombers would face at Pearl Harbor. In training, each crew flew over the 5,000 ft (1,500 m) mountain behind Kagoshima. They then dove into the city, avoiding buildings and smokestacks. They dropped to 25 ft (7.6 m) at the piers. Bombardiers released torpedoes at a breakwater about 300 yd (270 m) away.

However, even this low-altitude approach would not solve the problem of torpedoes hitting the bottom in Pearl Harbor's shallow waters. Japanese weapons engineers created and tested changes that allowed successful shallow water drops. This effort led to a heavily changed version of the Type 91 torpedo. This torpedo caused most of the ship damage during the actual attack. Japanese weapons experts also made special armor-piercing bombs. They did this by adding fins and release parts to 14- and 16-inch (356- and 406-mm) naval shells. These bombs could go through the lightly armored decks of the old battleships.

Idea of Invading Hawaii

At several points in 1941, Japan's military leaders talked about the chance of invading and taking over the Hawaiian Islands. This would give Japan a key base to protect its new empire. It would also stop the U.S. from having any bases beyond the West Coast. And it would further isolate Australia and New Zealand.

Genda believed Hawaii was vital for American operations against Japan once war started. He thought Japan must follow any attack on Pearl Harbor with an invasion of Hawaii, or risk losing the war. He saw Hawaii as a base to threaten the west coast of North America. He also thought it could be a tool for ending the war. He believed that after a successful air attack, 10,000-15,000 men could capture Hawaii. He saw this operation as a step before or an alternative to a Japanese invasion of the Philippines. In September 1941, Commander Yasuji Watanabe of the Combined Fleet staff estimated that two divisions (30,000 men) and 80 ships, plus the carrier strike force, could capture the islands. He found two possible landing spots, near Haleiwa and Kaneohe Bay. He suggested using both in an operation that would take up to four weeks with Japanese air superiority.

Even though this idea got some support, it was soon dropped for several reasons:

- Japan's ground forces, supplies, and resources were already fully busy. They were fighting the Second Sino-Japanese War. They also had planned offensives in Southeast Asia that were supposed to happen almost at the same time as the Pearl Harbor attack.

- The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) insisted it needed to focus on operations in China and Southeast Asia. It refused to give much support elsewhere. Because the army and navy didn't work together well, the IJN never discussed the Hawaiian invasion idea with the IJA.

Since an invasion was ruled out, they agreed that a huge carrier-based air attack on Pearl Harbor to destroy the Pacific Fleet would be enough. Japanese planners knew that Hawaii, being in the middle of the Pacific, would be a very important base for the U.S. to use its military power against Japan. However, Japan's leaders were confident the war would end quickly. They believed the U.S. would choose to negotiate a compromise instead of fighting a long, bloody war. This confidence outweighed their concern about Hawaii.

Watanabe's boss, Captain Kameto Kuroshima, thought the invasion plan was unrealistic. After the war, he called his rejection of it the "biggest mistake" of his life."

The Japanese Attack Force

On November 26, 1941, the same day the Hull note was received (which Japanese leaders saw as an unhelpful old proposal), the carrier force left Hitokappu Wan. This force was led by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo. They sailed towards Hawaii under strict radio silence.

In 1941, Japan was one of the few countries that could use aircraft carriers well. The Kido Butai, which was the Combined Fleet's main carrier force, had six aircraft carriers. This was the most powerful carrier force with the most air power in naval history at that time. It carried 359 airplanes, organized as the First Air Fleet. The carriers Akagi (the lead ship), Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, and the newest ones, Shōkaku and Zuikaku, had 135 Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 fighters (called "Zero" by the Allies). They also had 171 Nakajima B5N Type 97 torpedo bombers (called "Kate" by the Allies), and 108 Aichi D3A Type 99 dive bombers (called "Val" by the Allies). Two fast battleships, two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, nine destroyers, and three fleet submarines protected them. In addition, the Advanced Expeditionary Force included 20 fleet submarines and five small, two-man Ko-hyoteki midget submarines. These were meant to gather information and sink U.S. ships trying to escape Pearl Harbor during or after the attack. The force also had eight oilers for refueling at sea.

The Order to Attack

On December 1, 1941, after the attack force was already on its way, Chief of Staff Nagano gave an order to Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. He told him: "Japan has decided to open hostilities against the United States, United Kingdom, and the Netherlands early in December...Should it appear certain that Japanese-American negotiations will reach an amicable settlement prior to the commencement of hostilities, it is understood that all elements of the Combined Fleet are to be assembled and returned to their bases in accordance with separate orders. [The Kido Butai will] proceed to the Hawaiian Area with utmost secrecy and, at the outbreak of the war, will launch a resolute surprise attack on and deal a fatal blow to the enemy fleet in the Hawaiian Area. The initial air attack is scheduled at 0330 hours, X Day." After the attack, the force was to return to Japan, get new equipment, and prepare for "Second Phase Operations."

Finally, Order number 9, issued on December 1, 1941, by Nagano, told Yamamoto to destroy enemy naval and air forces in Asia, the Pacific, and Hawaii. It also ordered him to quickly seize the main U.S., British, and Dutch bases in East Asia and "capture and secure the key areas of the southern regions."

On the way back, the force was told to be ready for the Americans to track and counterattack them. They were ordered to return to a friendly base in the Marshall Islands, not to Japan.

Lack of Preparation by the U.S.

In 1924, General William L. Mitchell wrote a report warning that future wars, including with Japan, would involve planes attacking ships and bases. He even talked about a possible air attack on Pearl Harbor, but his warnings were ignored. Navy Secretary Knox also understood the chance of an attack at Pearl Harbor. He wrote about it shortly after taking office. American commanders had been warned that tests showed shallow-water torpedo attacks from planes were possible. But no one in charge in Hawaii fully understood this danger. In a 1932 fleet problem (a military exercise), a surprise airstrike led by Admiral Harry E. Yarnell was seen as a success and caused a lot of damage. This was confirmed in a 1938 exercise by Admiral Ernest King. In October 1941, Lord Louis Mountbatten visited Pearl Harbor. While teaching American naval officers about British tactics against the Germans, an officer asked when and how the U.S. would enter the war. Mountbatten pointed to Pearl Harbor on a map and said "right here." He mentioned Japan's surprise attack on Port Arthur and the British attack on Taranto. In Washington, he warned Stark about how unprepared the base was for a bomber attack. Stark replied, "I'm afraid that putting some of your recommendations into effect is going to make your visit out there very expensive for the U.S. Navy."

By 1941, U.S. signals intelligence, through the Army's Signal Intelligence Service and the Office of Naval Intelligence's OP-20-G, had intercepted and decoded many Japanese diplomatic and naval cipher messages. However, nothing really important about Japanese military plans in 1940–41 was found. Decoding and sharing this information was not always done well. This was partly due to a lack of resources and people. The information available to decision-makers in Washington was often incomplete, confusing, or not shared properly. It was also mostly raw data, without helpful analysis. So, it was not fully understood. Nothing in it directly pointed to an attack at Pearl Harbor. And because they didn't fully know what the Imperial Navy could do, there was a widespread belief that Pearl Harbor could not be attacked. Only one message from the Hawaiian Japanese consulate (sent on December 6), in a low-level consular code, mentioned an attack at Pearl. But it wasn't decoded until December 8. While the Japanese Diplomatic codes (Purple code) could be read, the current version (JN-25C) of the Japanese Naval code (JN-25), which replaced JN-25B on December 4, 1941, could not be read until May 1942.

U.S. intelligence, both civilian and military, had good information suggesting more Japanese aggression throughout the summer and fall before the attack. At the time, no reports specifically pointed to an attack against Pearl Harbor. Public news reports during summer and fall, including Hawaiian newspapers, had many stories about the growing tension in the Pacific. In late November, all Pacific commands, including both the Navy and Army in Hawaii, were clearly warned that war with Japan was expected very soon. It was preferred that Japan make the first hostile move. It was thought that war would most likely start with attacks in the Far East: the Philippines, Indochina, Thailand, or the Russian Far East. Pearl Harbor was never mentioned as a possible target. The warnings were not specific to any area. They only noted that war with Japan was expected soon and all commands should prepare. If any of these warnings had led to an active alert in Hawaii, the attack might have been fought back more effectively. This might have resulted in fewer deaths and less damage. On the other hand, calling men on shore leave back to the ships might have caused even more casualties from bombs and torpedoes. Or they could have been trapped in capsized ships by closed watertight doors (as an attack alert would require). Or they could have been killed in their old planes by more experienced Japanese pilots. When the attack actually happened, Pearl Harbor was not ready. Anti-aircraft weapons were not manned, most ammunition was locked away, anti-submarine measures were not in place (for example, no torpedo nets in the harbor), combat air patrols were not flying, available scouting planes were not in the air at first light, and Air Corps planes were parked wingtip to wingtip to reduce sabotage risks (not ready to fly quickly).

However, because it was believed Pearl Harbor had natural defenses against torpedo attacks (like the shallow water), the Navy did not use torpedo nets or barriers. These were thought to make normal operations difficult. Because there were limited numbers of long-range aircraft (including Army Air Corps bombers), reconnaissance patrols were not done as often or as far out as needed for good coverage against a surprise attack. (They improved a lot, with far fewer planes left, after the attack). The Navy had 33 PBYs in the islands, but only three were on patrol at the time of the attack. Hawaii was low on the priority list for the B-17 bombers that were finally becoming available for the Pacific. This was largely because General MacArthur in the Philippines was successfully asking for as many as possible for the Pacific (where they were meant to deter Japan). The British, who had ordered these planes, even agreed to take fewer to help this buildup. At the time of the attack, both the Army and Navy were in training status, not on full alert.

There was also confusion about the Army's readiness. General Short had changed local alert level names without clearly telling Washington. Most of the Army's mobile anti-aircraft guns were stored away, with ammunition locked in armories. To avoid upsetting property owners, and following Washington's advice not to alarm civilians (for example, in the late November war warning messages), guns were not spread around Pearl Harbor (on private property). Also, planes were parked close together on airfields to reduce the risk of sabotage, not because they expected an air attack. This was in line with Short's understanding of the war warnings.

Chester Nimitz later said, "It was God's mercy that our fleet was in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941." Nimitz believed if Kimmel had found out about the Japanese approach, he would have sailed out to meet them. With the three American aircraft carriers (Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga) absent and Kimmel's battleships at a big disadvantage against the Japanese carriers, the likely result would have been the sinking of the American battleships at sea in deep water. There, they would have been lost forever with huge casualties (as many as twenty thousand dead). Instead, they were in Pearl Harbor, where crews could easily be rescued, and six battleships were eventually raised.

Images for kids

-

Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano

-

Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, commanding general of the Army post at Pearl Harbor

-

Planner Commander Minoru Genda stressed surprise would be critical.

See also

In Spanish: Acontecimientos que condujeron al ataque a Pearl Harbor para niños

In Spanish: Acontecimientos que condujeron al ataque a Pearl Harbor para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |