Glacier Bay Basin facts for kids

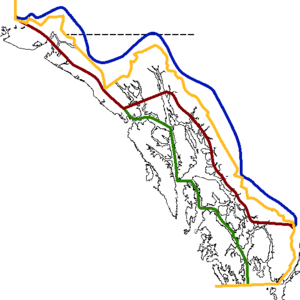

Quick facts for kids Glacier Bay, Alaska |

|

|---|---|

Landsat map of Glacier Bay

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

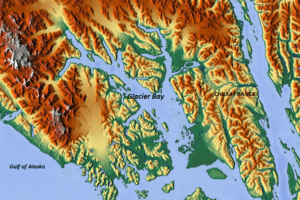

Landsat image of Glacier Bay

|

|

| Location | Alaska, United States |

| Type | Bay |

| Primary inflows | Pacific Ocean |

| Basin countries | United States and Canada |

| Max. length | 65 miles (105 km) |

| Max. width | 15 miles (24 km) |

| Surface area | 3,283,000 acres (1,329,000 ha) |

| Average depth | 800 feet (240 m) |

| Max. depth | 1,410 feet (430 m) |

Glacier Bay is a huge natural area in southeastern Alaska, United States. It includes the beautiful Glacier Bay itself, along with tall mountains and massive glaciers all around it. This special place was first protected as a U.S. National Monument in 1925. Later, in 1980, it became the much larger Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, covering about 3.3 million acres (1.3 million hectares).

In 1986, a part of the park was named a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, which is like a special protected area for nature. This is actually the biggest protected biosphere in the world! A few years later, in 1992, UNESCO added this area to a World Heritage site. This huge site also includes other parks in Alaska and Canada, making it a massive protected natural space. A large part of the National Park is also set aside as a Wilderness area, meaning it's kept as wild and untouched as possible.

Today, glaciers cover about 1,375 square miles (3,560 square kilometers), which is about 27% of the park. A long time ago, around the early 1700s, this whole area was covered by one giant glacier. But over the last 200 years, the ice has melted and moved back, creating 65 miles (105 kilometers) of ocean bay. As it retreated, it left behind about 20 smaller, separate glaciers. In 1890, a U.S. Navy captain named Lester A. Beardslee officially named it "Glacier Bay."

Glacier Bay has many different parts, like branches, narrow inlets, lagoons, islands, and channels. This makes it a great place for scientists to study and for people to visit and enjoy the amazing views. It's a very popular spot for cruise ships in the summer. However, the National Park Service limits how many boats can be in the bay each day to protect the environment.

Contents

History of Glacier Bay

Scientists believe that Glacier Bay has been shaped by at least four major ice ages, with the most recent one being the "Little Ice Age" which ended about 4,000 years ago. All the glaciers you see in the park today are what's left from that last ice age.

The first written records of the Glacier Bay area come from a Russian expedition in 1741. Later, in 1786, a French explorer named La Perouse met the local people, the Tlingits, at Lutya Bay. After this, Russia claimed the region.

In 1794, a British explorer named Joseph Whidbey, who was with George Vancouver's expedition, reported that a huge wall of ice, about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) wide and 3,900 feet (1,200 meters) thick, blocked his way. Vancouver claimed the land for Britain, but Russia had already claimed it. This disagreement was settled by a treaty in 1825. When the United States bought Alaska from Russia in 1867, they also got the claim to this land. The exact border between the U.S. and Canada was decided by a special group in 1903. This agreement meant that even as the glaciers melt and the coastline changes, the border stays in the same place.

When gold was discovered in the area, miners came to Glacier Bay. In the 1890s, a salt mine was started, along with fox farms and a fish cannery. However, the cannery was closed in 1935.

John Muir, a famous naturalist and scientist, helped bring attention to Glacier Bay. He studied the glaciers and saw how much they had melted. When he first visited the bay in 1888 or 1889, the main ice wall was about 48 miles (77 kilometers) long and had moved back 44 miles (71 kilometers) from the sea. Now, it has moved back 65 miles (105 kilometers) and has become 16 main tidewater glaciers.

In 1899, a rich businessman named Edward Harriman organized a trip to Alaska called the Harriman Alaska expedition. He brought many scientists, artists, and photographers to explore and record the Alaskan coast. This expedition helped document how much the glaciers had melted by 1899. John Muir and Harriman also helped convince the government to create national parks.

The first tourist ship arrived at Bartlett Cove, near the entrance of the bay, in 1893. This area has since become a main spot for tourists. By 1916, the Grand Pacific Glacier had moved all the way to the end of Tarr Inlet, about 65 miles (105 kilometers) from the bay's mouth. This is one of the fastest glacier retreats ever recorded! In 1925, Glacier Bay was officially made a national monument.

For many centuries, Glacier Bay has been the homeland of the Huna Tlingit native people of Alaska. Their stories tell how they had to move away when the glacier grew very large. They started moving back to the area when the glacier began to melt in the 1880s. Their culture is deeply connected to the bay.

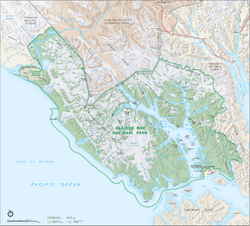

Geography of Glacier Bay

Glacier Bay is part of a much larger National Park and Preserve. This park is an amazing mix of ocean and land life. It is surrounded by the Tongass National Forest to the east and northeast, and by a Canadian park called Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park to the north. To the south, it meets the waters of Cross Sound and Icy Strait, and to the west, the Pacific Ocean. When President Calvin Coolidge made Glacier Bay a national monument in 1925, he wanted to protect its unique glaciers, mountains, forests, and wildlife. He also wanted to allow scientists to study how the land and living things change as the ice melts.

The Glacier Bay area now has a mix of tidewater glaciers (which flow into the sea), snow-covered mountains, ocean coastlines, deep fjords (narrow inlets of the sea), and freshwater rivers and lakes. This creates many different types of landscapes and is home to a wide variety of plants and animals.

About 27% of Glacier Bay is covered by glaciers, which means about 1,375 square miles (3,560 square kilometers) of ice! Most of these glaciers start in mountains that are 8,000 to 15,000 feet (2,400 to 4,600 meters) high. There are over 50 named glaciers here. Ten of them are tidewater glaciers, meaning they reach the ocean and break off into icebergs. Seven of these are still active, creating loud "calving" sounds as huge chunks of ice crash into the sea. The McBride Glacier is the only tidewater glacier on the eastern side of the bay. On the western side, the Johns Hopkins Glacier and Margerie Glacier are well-known.

The National Park Service manages a large area of marine waters in Glacier Bay, covering about 607,099 acres (245,684 hectares). The coastline of the bay, including all its islands, is about 760 miles (1,223 kilometers) long. The deepest part of the bay is 1,410 feet (430 meters) below sea level. The tides here change every 6 hours, with the water level rising and falling by up to 18 feet (5.5 meters).

Most glaciers in Glacier Bay are melting and moving back. However, the Johns Hopkins Glacier is actually growing, and the Margerie Glacier is staying about the same size. Scientists believe that less snowfall in the mountains, warmer winter temperatures, and less cloud cover in summer are causing the glaciers to melt.

After the Little Ice Age, the land in Glacier Bay has been slowly rising. This is because the heavy weight of the ice has melted, and the Earth's crust is bouncing back up. This rising land changes the shorelines and affects rivers, erosion, and how much sediment is deposited. All these changes have a big impact on the plants and animals in the park.

You can only reach Glacier Bay by boats or ships. There are also about 10 miles (16 kilometers) of hiking trails and 700 miles (1,126 kilometers) of shoreline for kayaking. The closest town with a road and airport is Gustavus, which is the main entry point to Glacier Bay. However, you can only get to Gustavus by air or sea. Juneau, the capital of Alaska, is about 60 miles (97 kilometers) away.

Glaciers move because snow turns into ice on the hills, and then this ice slides down due to gravity. They grow when it's cold all year round and they are protected by rock and rubble. When temperatures rise or the protection decreases, the glaciers start to melt and move back. Another interesting thing that happens with many glaciers in Glacier Bay is "calving." This is when large blocks of ice break off from the glacier and crash into the sea, making a loud noise and big waves. This can happen at any time, no matter the weather.

Glacier Bay was closed to ships for almost ten years after a big earthquake in 1899. This was because the earthquake caused so many ice blocks to break off and fill the bay. Even though the bay is in a region with volcanic activity, no active volcanoes have been found directly in Glacier Bay. However, earthquakes and volcanic activity can still affect the environment here.

Ancient Discoveries

Scientists have found ancient remains at two sites in Glacier Bay, showing that people lived here thousands of years ago. On Baranof Island, tools and other items show people lived there between 3,200 and 4,600 years ago. Another discovery, a house and tools at Ground Hog Bay, dates back about 2,000 years. These findings suggest that the culture of the people living here long ago was similar to the native groups who lived on the Northwest Coast more recently. Scientists believe there are likely many more ancient sites waiting to be discovered.

The Tlingit People

The Tlingit people consider Glacier Bay their sacred homeland. The National Park Service recognizes that the park is very important to the Huna Tlingit and Ghunaaxhoo Kwaan tribes. Their oral traditions say that they were forced to move south when the glacier grew very large. They moved back to the area in the 1880s as the glacier retreated. There are many old sites in Glacier Bay linked to the Tlingit people or early European Americans.

The Tlingit traditionally lived by hunting, gathering, and fishing, especially for salmon. They had a complex society with rich artistic traditions. They felt that when the area was a National Monument, it helped protect their fishing lifestyle by keeping out commercial fishing. When it became a National Park, some of their fishing and hunting activities were limited, except for certain religious reasons. However, the National Park works closely with the Tlingit to help them keep their culture alive. They are allowed to enter the park to gather berries, seafood, and materials like spruce roots and mountain goat hair for weaving traditional blankets. The park also plans to build a Tlingit longhouse near its main office to highlight Tlingit culture and host cultural events.

Climate of Glacier Bay

Glacier Bay has a cool, wet, coastal climate, similar to a temperate rainforest. There are three different climate zones in the bay:

- The outer coast along the Gulf of Alaska has mild temperatures and a lot of rain, but less snow.

- The upper Glacier Bay is much colder and gets heavy snowfall.

- The lower Glacier Bay gets heavy rainfall all year round.

In general, summer temperatures in the bay are between 50°F (10°C) and 60°F (16°C). Winter temperatures are usually between 20°F (-7°C) and 30°F (-1°C), but can drop as low as -10°F (-23°C).

On average, it rains or snows about 228 days a year. The area gets about 70 to 80 inches (178 to 203 centimeters) of rain each year, including about 14 feet (4.3 meters) of snow. The highest snowfall ever recorded was an amazing 100 feet (30 meters) in the Fairweather Mountains!

Plants and Animals

The environment of Glacier Bay has four main land ecosystems: wet tundra (a treeless plain), coastal western hemlock/Sitka spruce forests, alpine tundra (high mountain plains), and glaciers and ice fields. Within the bay itself, there are three main marine ecosystems: the continental shelf, wave-beaten coasts, and fjord estuaries (where rivers meet the sea).

As the glaciers melted and moved back, plants slowly started to grow in the newly exposed land. So, at the entrance of the bay, you can find 200-year-old spruce and hemlock forests. But closer to the head of the bay, where the ice has only recently melted, you'll see simpler plants like mosses and lichens. Because of climate change, some glaciers are now melting even faster, up to a quarter of a mile (0.4 kilometers) per year.

When the glaciers moved back, they uncovered new land. This allowed new plant and animal communities to grow, from "pioneer species" (the first ones to appear) in recently exposed areas to older, more developed ecosystems in coastal and mountain regions.

Wildlife

Glacier Bay is home to many different kinds of wildlife. Scientists have recorded 160 types of marine and estuarine fish, 242 bird species, and 41 different kinds of mammals.

Bears

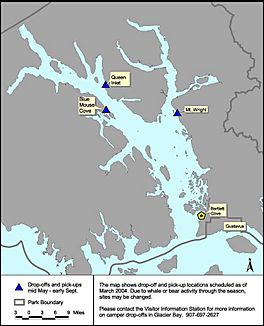

Both black and brown Bears are often seen in Glacier Bay, especially along the shorelines where they look for food. They sometimes scrape barnacles off rocks and eat mussels. You might spot them walking alone along the beaches, looking for salmon. Black bears usually live in the southern forested areas of the bay. Brown bears are more common in the northern areas, where the glaciers have recently melted. Sometimes, black bears are seen near the glaciers or the town of Gustavus. Bears often travel along easy paths like beaches, stream beds, and river valleys.

Some common places to see black bears are Bartlett Cove, the Bartlett River, the Beardslee Islands, and North and South Sandy Cove. Brown bears are often seen north of Tidal Inlet in the west arm of the glacier and north of Adams Inlet in the east arm. Bears are also known to swim across the bay. Their favorite food is salmon, but they also eat bumblebees, sand fleas, bird eggs, small birds, voles, and dead marine animals.

Whales

Humpback whales are often seen in the lower part of Glacier Bay, as well as in Sitakaday Narrows, Whidbey Passage, and around South Marble Island. If you're kayaking, Hugh Miller Inlet and the Beardslee Islands are good places to see humpback whales from a safe distance. Other types of whales you might see include grey, minke, fin, and killer whales (also called orcas).

Seals and Porpoises

You can also spot Harbor seals, northern fur seals, sea otters, harbor porpoises, Dall's porpoises, and Steller sea lions in Glacier Bay.

Other Mammals

Other land mammals found in Glacier Bay include blue bears (a type of glacier bear), moose, Sitka black-tailed deer, mountain goats, wolfes, coyotes, lynxes, wolverines, marmots, land and river otters, weasels, ermine, mink, squirrels, beavers, and red foxes. You might also find porcupines, voles, shrews, hares, and bats.

Birds

Over 200 different bird species have been recorded in the bay. These include: the bald eagle, golden eagle, raven, northern hawk owl, sandhill crane, loon, Steller's jay, murre, cormorant, puffin, murrelet, oystercatchers, herons, geese, ducks, ptarmigan, crow, osprey, blue grouse, woodpecker, pigeon guillemot, sparrow, sandpiper, plover, Arctic tern, kittiwake, and gulls.

Fish and Shellfish

Fish species found in the bay include: Chinook, chum, sockeye, pink, and coho salmon, halibut, trout, steelhead, Dolly Varden, lingcod, whitefish, blackfish, char, and herring. For shellfish, there are Dungeness crabs, scallops, shrimp, and clams. Salmon are a very important food source for bears, especially in late summer and fall. The southern part of the bay has many salmon streams. As glaciers melt in the northern bay, new streams are forming, and salmon are starting to live there too. This means more food for bears in the future!

Vegetation

As the Glacier Bay glacier has melted over the last 300 years, new plants have started to grow and spread across the land. This process has created a new coastal forest. Scientists have found 333 different types of Vascular plants in Glacier Bay. Along the shoreline, you'll find dense groups of Sitka alder and devil's club.

Famous Landmarks

Glacier Bay has about 50 identified glaciers, some that flow into the sea (tidewater) and some that stay on land (terrestrial). Here are some of the main inlets, glaciers, and mountains you can find:

At the entrance to the bay, you'll find the small town of Gustavus, the National Park Service Visitor Center, and the Glacier Bay Lodge. The main channel has several islands. On the western side of the channel, the first inlet is Muir Inlet, which has several smaller inlets and glaciers like Adam's Inlet, Casement Glacier, McBride Glacier, Riggs Glacier, and Muir Glacier.

Further north along the main bay, on the west shore, are the Gelkie Inlet, Reid Glacier, and Lamplugh Glacier, which are fed by the Brady Icefield and Brady Glacier. Beyond these are the Johns Hopkins Glacier, Margerie Glacier, and the Great Pacific Glacier at the very end of the bay. The east shoreline has the Queen Inlet with its Carroll Glacier, and the Rendu Inlet with its Rendu Glacier.

The Fairweather Range of mountains forms the western edge of Glacier Bay and feeds the Johns Hopkins and Margerie Glaciers. The tallest mountains here include Mount Fairweather (15,300 feet or 4,663 meters), Mt. Quincy Adams (13,650 feet or 4,161 meters), and Mt. Crillon (12,276 feet or 3,742 meters). A major island, Russel Island, is located in the middle of the main channel, opposite the Johns Hopkins Inlet.

Muir Glacier

The Muir Glacier was named after John Muir, who first saw it in 1889. It used to be a tidewater glacier, meaning it flowed into the sea, and was about 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) wide and 265 feet (81 meters) tall. However, it has now become a terrestrial glacier, meaning it no longer reaches the sea. It has melted back very quickly since the Little Ice Age around 1780. During its retreat, which started in 1889, large chunks of ice broke off often. It moved back about 6,000 feet (1,829 meters) per year until 1979, and by 1993, it was completely on land. Today, the glacier is only about 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) wide and 150 feet (46 meters) tall, stretching for 13 miles (21 kilometers). Its tributary, Morse Glacier, is also melting quickly. As it retreated, the glacier left behind two large deltas of rock and rubble.

Reid Glacier

The Reid Glacier was named by the Harriman Alaska expedition for Harry Fielding Reid, a geology professor who studied glaciers. This glacier starts in the Brady Icefield and moves about 15 feet (4.6 meters) per day. Where it meets the water, it is about 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometers) wide, rises 150 feet (46 meters) high, and stretches for 10 miles (16 kilometers). Because it's melting so fast, this glacier has also mostly become a terrestrial glacier, especially on its eastern and western sides. Sediment from the glacier has filled in these areas, especially at low tide. However, the middle part of the glacier still touches the water, with a depth of about 30 feet (9 meters) at high tide.

Lamplugh Glacier

The Lamplugh Glacier was named after an English geologist, George William Lamplugh, who visited Glacier Bay in 1884. This glacier starts in the Brady Icefield. It is about 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometers) wide where it meets the water, and its ice face is about 150 to 160 feet (46 to 49 meters) high, with water depths of 10 to 40 feet (3 to 12 meters). The glacier stretches for over 16 miles (26 kilometers). The ice flows from the glacier at about 900 to 1,000 feet (274 to 305 meters) per year. The central and eastern parts of the glacier are melting due to calving (ice breaking off), but the western part is mostly on land, except at high tide. A stream has formed under the central part of the glacier, and it moves around, creating a delta of sediment at low tide. This also makes the water look milky brown.

Johns Hopkins Inlet

The Johns Hopkins Inlet is a stunning 9-mile (14-kilometer) long fjord with several tidewater glaciers. The Lamplugh Glacier is about 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) away from the inlet. Further inside is the Johns Hopkins Glacier, which is the largest tidewater glacier in Glacier Bay. Nearby are the Gilman Glacier and Hoonah Glacier. All these glaciers flow into the sea. Many ice blocks float in the inlet, making it dangerous for boating or kayaking. To protect young harbor seals, Johns Hopkins Inlet is closed to boats in May and June.

Johns Hopkins Glacier

The Johns Hopkins Glacier starts in the Fairweather Range and flows east towards the end of Johns Hopkins Inlet. Its rock, ice, and snow show beautiful colors like grey, blue, and white. It was named in 1893 after Johns Hopkins University, which supported an expedition to this glacier. This is the only tidewater glacier in the bay that is currently growing. It started advancing in 1924. The Gilman Glacier has joined with it several times and appears to be joined again since 2000. Together, they form one large block of ice that is advancing. At the waterfront, it is about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) wide, 250 feet (76 meters) deep, and rises 250 feet (76 meters) high, stretching about 12 miles (19 kilometers) upstream. Ice also breaks off underwater.

Because so many ice blocks break off from its cliffs, boats cannot get closer than about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) to the Johns Hopkins Glacier. Most visitors see the glaciers from cruise ships.

Gilman Glacier

The Gilman Glacier joined the Johns Hopkins Glacier around 1990. Over the next ten years, the two glaciers merged and separated several times. However, since 2000, they have been joined again and are advancing together along a steep ice face that is 150 to 200 feet (46 to 61 meters) high.

Tarr Inlet

Tarr Inlet, at the very end of Glacier Bay, is a beautiful scene of ice and snow. It offers excellent views of the Grand Pacific Glacier to the north and the Margerie Glacier to the west. The western shoreline of this inlet is steep and rocky, stretching for 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) up to a small stream with a beach. Further along, a glacier knob is seen in the middle of the west shore, forming a cove that is good for camping, though it can be windy with ice flows. This spot also provides a great view of Tarr Inlet. The Margerie Glacier is 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) north of this location. The Grand Pacific Glacier is to the east of the Margerie Glacier, at the head of Tarr Inlet, where you can see a lot of gravel left by the glacier. From the Grand Pacific, Tarr Inlet continues for 5 miles (8 kilometers) with a steep gravel shoreline and small streams.

Margerie Glacier

The Margerie Glacier is a 21-mile (34-kilometer) long tidewater glacier. It starts on the south side of Mount Root, near the Alaska-Canada border, and flows southeast and northeast into Tarr Inlet. It was named after a famous French geographer and geologist, Emmanuel de Margerie, who visited Glacier Bay in 1913. Located at the deep end of Glacier Bay, Margerie Glacier is about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) wide and stretches 21 miles (34 kilometers) upstream to its source on Mount Root. Mount Root is a mountain in Alaska and British Columbia, part of the Fairweather Range.

Grand Pacific Glacier

The Grand Pacific Glacier, at the head of Tarr Inlet, has a face covered with gravel and stones that are often more than 3 feet (0.9 meters) thick. Landslides and piles of rock and dirt cover much of the eastern side of the glacier. This glacier is not very active. In the early 1700s, it was one huge block of ice at the Gulf of Alaska when Captain Vancouver first saw it. It has since melted back to its current location, which is 65 miles (105 kilometers) from the entrance of Glacier Bay. At its current spot, the Grand Pacific Glacier is about 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) wide, with water 30 feet (9 meters) deep in front of it. It rises about 150 feet (46 meters) high and stretches for 35 miles (56 kilometers). It calves into Tarr Inlet, and its western two-thirds are formed by the Ferris Glacier. It moves about 1,500 feet (457 meters) per year, or about 4 feet (1.2 meters) per day. However, the eastern part of the glacier moves much slower, about 15 to 180 feet (4.6 to 55 meters) per year. The Margerie Glacier had merged with this glacier in 1992, but as the Grand Pacific Glacier melted back, they separated, and now only a small stream divides them.

Fairweather Range

The Fairweather Range is a mountain range in Alaska and British Columbia, Canada. It's the southernmost part of the Saint Elias Mountains. The northern part of the range is in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in Canada, while the southern part is in Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska. The peaks in this range include Mount Fairweather, which is the highest point in British Columbia, and Mount Quincy Adams.

Between the bay and the coast, the snow-covered peaks of the Fairweather Range catch the moisture coming from the Gulf of Alaska. This moisture then turns into snow and ice, feeding the park's largest glaciers. Mount Fairweather is the tallest peak in this range, and despite its name, it has very harsh weather.

Mount Fairweather

Mount Fairweather is located about 20 kilometers (12 miles) east of the Pacific Ocean in the Glacier Bay region. Most of the mountain is in Alaska, but its very top is also in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park in British Columbia, making it the highest point in that Canadian province. It's also known as Boundary Peak 164 because it's on the border. Captain James Cook named the mountain "Fairweather" on May 3, 1778, because the weather was unusually good that day. The name has been translated into different languages over time. Mount Fairweather was first climbed in 1931 by Allen Carpé and Terris Moore.

See also

In Spanish: Parque nacional y reserva de la Bahía de los Glaciares para niños

In Spanish: Parque nacional y reserva de la Bahía de los Glaciares para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |