Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Born | 4 December [O.S. 22 November] 1878 Anichkov Palace, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

||||

| Died | 13 June 1918 (aged 39) Perm, Russian Soviet Republic |

||||

| Spouse |

Natalia Brasova

(m. 1912) |

||||

| Issue | George Mikhailovich, Count Brasov | ||||

|

|||||

| House | Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp | ||||

| Father | Alexander III of Russia | ||||

| Mother | Dagmar of Denmark | ||||

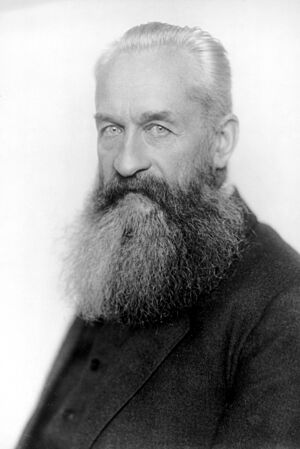

Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia (Russian: Михаи́л Алекса́ндрович; 4 December [O.S. 22 November] 1878 – 13 June 1918) was the youngest son of Emperor Alexander III of Russia. He was also the younger brother of Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia. For a short time in 1917, after his brother Nicholas II gave up his throne, Michael was named the next Emperor. However, Michael decided not to take the crown the very next day.

Michael was born when his grandfather, Alexander II, was still Emperor. He was fourth in line to the throne. After his grandfather was killed in 1881, Michael became third in line. In 1894, his father died, making him second in line. When his older brother George died in 1899, Michael became the next in line to the throne after Nicholas II.

In 1904, Nicholas's son, Alexei, was born. This moved Michael back to second in line. However, Alexei had a serious bleeding illness called hemophilia. Michael thought Alexei might not live, which would make him the next heir again. Michael caused a stir at the royal court when he fell in love with Natalia Sergeyevna Wulfert, who was already married. Nicholas sent Michael away to avoid scandal. But Michael still traveled often to see Natalia. After their only child, George, was born in 1910, Michael brought Natalia to St. Petersburg. However, high society did not accept her. In 1912, Michael surprised Nicholas by marrying Natalia. He hoped this would remove him from the line of succession. Michael and Natalia then left Russia to live in other countries like France, Switzerland, and England.

When World War I started, Michael returned to Russia. He took command of a cavalry division. In March 1917, when Nicholas gave up his throne, Michael was named as his successor instead of Alexei. But Michael said he would only accept the throne if the people voted for it later. He was never officially confirmed as emperor. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, he was imprisoned and later killed.

Contents

- Early Life of Grand Duke Michael

- Military Career and Public Duties

- Romances and Marriage

- World War I and Michael's Service

- War's Difficulties and Michael's Views

- Growing Public Unrest and Revolution

- The Revolution and Nicholas's Abdication

- Arrest and Imprisonment

- Life in Perm and Death

- Military Roles and Commands

- Honors and Awards

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life of Grand Duke Michael

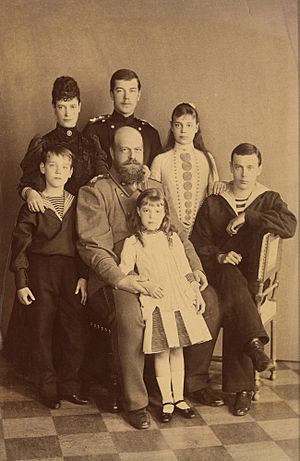

Michael was born at Anichkov Palace in Saint Petersburg. He was the youngest son of Tsesarevich Alexander and his wife, Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark). His grandparents on his mother's side were King Christian IX of Denmark and Louise of Hesse-Kassel. His grandmother on his father's side died before he was two years old. His grandfather, Emperor Alexander II of Russia, was killed in 1881. Because of this, Michael's parents became the Emperor and Empress of All the Russias before his third birthday. After the assassination, the new Tsar Alexander III moved his family, including Michael, to the safer Gatchina Palace. This palace was about 29 miles southwest of Saint Petersburg and had a moat around it.

Michael grew up with his younger sister, Olga. She called him "Floppy" because he would "flop" into chairs. His older siblings and parents called him "Misha." Their living conditions were simple. The children slept on hard beds, woke up early, washed in cold water, and ate plain porridge for breakfast. Michael, like his brothers and sisters, was taught by private teachers. An English nanny, Mrs. Elizabeth Franklin, took care of him.

Michael and Olga often hiked in the forests around Gatchina with their father. He taught them how to survive in the woods. They also learned physical activities like horseback riding from a young age. Religious practices were important too. Christmas and Easter were times of celebration. But during Lent, they strictly avoided meat, dairy, and entertainment. Family holidays were spent in the summer at Peterhof Palace and with Michael's grandparents in Denmark.

Michael was almost 16 when his father became very ill. The yearly trip to Denmark was canceled. On November 1, 1894, Alexander III died at 49 years old. Michael's oldest brother, Nicholas, became Tsar. This marked the end of Michael's childhood.

Military Career and Public Duties

Michael's mother, Dowager Empress Marie, moved back to Anichkov Palace with Michael and Olga. Like most men in his family, Michael joined the military. He finished training at a gunnery school. Then he joined the Horse Guards Artillery. In November 1898, he became an adult. Just eight months later, he became the next in line to the throne after Nicholas. This happened because his middle brother, George, died in a motorcycle accident. George's death showed that Nicholas did not have a son. Since only males could inherit the throne, Nicholas's three daughters were not eligible. When Nicholas's wife, Alexandra, became pregnant in 1900, she hoped for a boy. She tried to be named ruler if Nicholas died before their child was born. But the government disagreed. They decided that Michael would become emperor no matter the child's gender. The next year, she had a fourth daughter.

Michael was seen as a quiet and kind person. He carried out the public duties expected of someone next in line to the throne. In 1901, he represented Russia at the funeral of Queen Victoria. He received the Order of the Bath, an important honor. The next year, he was made a Knight of the Garter during King Edward VII's coronation. In June 1902, Michael moved to the Blue Cuirassier Regiment in Gatchina. Since becoming an adult, Michael had his own money. He owned the country's largest sugar refinery. He also had millions of rubles, a collection of cars, and country homes in Poland and near Orel.

Michael was next in line until August 12, 1904. That's when Tsarevich Alexei was born to Nicholas and Alexandra. Alexei became the direct heir. Michael was again second in line to the throne. However, he was named as a co-regent for Alexei, along with Alexandra, if Nicholas were to die.

Romances and Marriage

In 1902, Michael met Princess Beatrice of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. They fell in love and wrote letters to each other in English. Michael spoke both French and English very well. At first, it seemed they would marry. However, the Eastern Orthodox Church did not allow first cousins to marry. Michael's father and Beatrice's mother were brother and sister. Nicholas would not let them marry. So, to Michael's and Beatrice's sadness, their romance ended.

Michael then became interested in Alexandra Kossikovskaya, known as "Dina." She was a lady-in-waiting to his sister Olga. Dina's father was a lawyer, and Dina was a commoner (someone not from a royal family). In July 1906, Michael wrote to Nicholas asking permission to marry her. Nicholas and Dowager Empress Marie were very upset. They both believed that royals should only marry other royals. Also, Russian law stated that children from a marriage between a royal and a commoner could not inherit the throne. Nicholas threatened to remove Michael from the army and send him out of Russia if he married without permission. Marie had Dina removed from her job. She also took Michael to Denmark until mid-September.

Soon after he returned to Russia, some British newspapers wrongly announced that Michael would marry Princess Patricia of Connaught. But neither Michael nor Patricia knew anything about it. Buckingham Palace said it was not true. Two years later, in October 1908, Michael visited London. He and Patricia were seen together at social events. It seems Michael's mother was trying to get him to marry a more suitable bride. Michael and Dina were planning to secretly run away and marry. But Nicholas's secret police, the Okhrana, watched Dina and stopped her from traveling. Under family pressure, and unable to see Dina, Michael seemed to lose interest by August 1907. Dina went to live abroad. She never married, but their romance was over.

In late 1907, Michael met Natalia Sergeyevna Wulfert. She was married to a fellow officer. By 1908, they became very close friends. Natalia was a commoner and had a daughter from her first marriage. By August 1909, they were in love. By November 1909, Natalia was living separately from her second husband in an apartment paid for by Michael. To prevent scandal, Nicholas moved Michael to a different army unit far from Moscow. But Michael still traveled often to see Natalia. Their only child, George, was born in July 1910. This was before Natalia's divorce was final. To make sure the child was officially recognized as his, Michael arranged for the divorce date to be changed. Nicholas issued a decree giving the boy the last name "Brasov," from Michael's estate. This was a quiet way of admitting Michael was the father.

In May 1911, Nicholas allowed Natalia to move to Brasovo. He also granted her the last name "Brasova." In May 1912, Michael went to Denmark for a funeral. There, he became ill with a stomach ulcer. This problem bothered him for years. After a vacation in France, where he and Natalia were followed by the Okhrana, Michael was moved back to Saint Petersburg. He took Natalia to the capital and set her up in an apartment. But society did not accept her. Within a few months, he moved her to a villa in Gatchina.

In September 1912, Michael and Natalia went on a holiday abroad. As usual, the Okhrana followed them. In Berlin, Michael said he and Natalia would drive to Cannes. He told his staff to follow by train. The Okhrana was told to follow by train too, so Michael and Natalia would be alone on their trip south. Michael's journey was a trick. On the way to Cannes, they went to Vienna. There, they were married on October 16, 1912, in a Serbian Orthodox Church. A few days later, they arrived in Cannes. George and Natalia's daughter from her first marriage joined them. Two weeks after the wedding, Michael wrote to his mother and brother to tell them. They were both very upset. His mother said it was "unspeakably awful." His brother was shocked that Michael had "broken his word" not to marry her.

Nicholas was especially upset because his son, Alexei, was very ill with hemophilia. Michael said this was one reason he married Natalia. Michael feared he would become the next in line again if Alexei died. He worried he would never be able to marry Natalia then. By marrying her beforehand, he would be removed from the line of succession early. In late 1912 and early 1913, Nicholas issued several orders. He removed Michael from his command, banished him from Russia, froze all his money in Russia, took control of his estates, and removed him from the Regency. People in Russia were shocked by how harsh Nicholas's actions were. But there was little sympathy for Natalia. She was not allowed to be called Grand Duchess. Instead, she used the name "Madame or Countess Brasova."

For six months, they stayed in hotels in France and Switzerland. Their lifestyle did not change. Michael's sister Grand Duchess Xenia and cousin Grand Duke Andrew visited them. In July 1913, they saw Michael's mother in London. She told Natalia "a few home truths," according to Xenia's diary. After another trip to Europe, Michael rented Knebworth House, a large home north of London, for a year. Michael's money was tight. He had to rely on payments sent from Russia by Nicholas's order. Nicholas still controlled all his estates and money.

World War I and Michael's Service

Upon the start of World War I in 1914, Michael sent a telegram to the Emperor. He asked for permission to return to Russia to serve in the army. He also asked if his wife and son could come too. Nicholas agreed. Michael traveled back to Saint Petersburg through several countries. Michael had already rented Paddockhurst in England, a larger estate. He had planned to move there after his lease at Knebworth ended. He moved his furniture there. People did not expect the war to last long. The couple thought they would move back to England when it was over. Meanwhile, Michael offered his estate for use by the British military. In Saint Petersburg, renamed Petrograd in September 1914, they moved into a villa in Gatchina that Michael had bought for Natalia. Natalia was not allowed to live in any of the imperial palaces.

The Grand Duke was promoted from colonel to major-general. He received command of a new division called the Caucasian Native Cavalry. This division became known as the "Savage Division." This appointment was seen as a step down. The division was mostly made up of new Muslim recruits, not the elite troops Michael had commanded before. The six regiments in the division each had a different ethnic group: Chechens, Dagestanis, Kabardin, Tatars, Circassians, and Ingush. They were commanded by Russian officers. All the men were volunteers, as conscription did not apply to the Caucasus region. Even though it was hard to keep discipline, they were good fighters. For his actions leading his troops in the Carpathian mountains in January 1915, Michael earned the military's highest honor, the Order of St. George, 4th Class. Unlike his brother the Emperor, he was a popular military leader.

By January 1915, the terrible nature of the war was clear. Michael felt "greatly upset towards people in general." He especially felt this way about "those who are at the top, who hold power and allow all that horror to happen." Michael wrote to his wife that he felt "ashamed to face the people, i.e. the soldiers and officers." He felt this way "particularly when visiting field hospitals, where so much suffering is to be seen." He thought they might believe he was also responsible for the war.

At the start of the war, Michael wrote to Nicholas. He asked him to officially recognize his son. This would ensure the boy would be cared for if Michael died in the war. Nicholas finally agreed to make George legitimate. He granted him the title "Count Brasov" by decree on March 26, 1915.

War's Difficulties and Michael's Views

By June 1915, the Russians were retreating. When Grand Duke Constantine died that month, Michael was the only member of the imperial family not at the funeral in Petrograd. Natalia scolded him for not being there. Michael replied that it was wrong for his relatives to leave their units to attend a funeral at such a time. An American war reporter, Stanley Washburn, said Michael wore "a simple uniform with nothing to indicate his rank." Michael was "unaffected and democratic" and "living so simply in a dirty village." Natalia was upset that Michael chose simple uniforms over fancy ones for life at the front. But he was sure "that at such a difficult time I must serve Russia and serve here at the front."

In July 1915, Michael caught diphtheria but recovered. The war was going badly for Russia. The next month, Nicholas named himself Supreme Commander of the Russian forces. This decision was not popular. Nicholas made bad choices. For example, he told Michael to approve a payment to a friend of Rasputin. This friend was an army engineer who claimed to have invented a powerful flame-thrower. The claim was false, and the engineer was arrested for fraud. But Rasputin stepped in, and he was released. Michael seemed easily fooled and innocent. A friend of Natalia's said he "trusted everybody... Had his wife not watched over him constantly, he would have been deceived at every step."

In October 1915, Michael got back control of his estates and money from Nicholas. In February 1916, he was given command of the 2nd Cavalry Corps. This included the Savage Division and two Cossack divisions. However, the Tsar's close circle continued to disrespect him. When he was promoted to lieutenant-general in July 1916, he was not made an aide-de-camp to the Tsar. All other Grand Dukes who reached that rank were. Michael admitted that he "always disliked Petrograd high society... no people are more dishonest than they are." Michael made no public political statements. But people thought he was a liberal, like his wife. British consul Bruce Lockhart believed he "would have made an excellent constitutional monarch."

Throughout the summer of 1916, Michael's corps fought in the Brusilov Offensive. The Guards Army suffered heavy losses under the poor leadership of Michael's uncle, Grand Duke Paul. He was removed from command. In contrast, Michael received a second medal for bravery. This was the Order of St. Vladimir with Swords, for his actions against the enemy. He was later made an adjutant-general. The war's poor progress and their almost constant separation made both Michael and Natalia sad. Michael still suffered from stomach ulcers. In October 1916, he was told to take leave in the Crimea.

Before going to his sister Xenia's estate, he wrote a frank letter to his brother. He warned him that the political situation was tense:

I am deeply concerned and worried by what is happening around us. There has been a shocking change in the mood of the most loyal people... which fills me with a most serious fear not only for you and for the fate of our family, but even for the safety of the state.

The public hatred for certain people who are said to be close to you and who are part of the current government has, to my surprise, brought together all groups; and this hatred, along with the demands for changes, are already openly expressed.

Growing Public Unrest and Revolution

Michael and other members of the royal family warned about the growing public unrest. They also warned about the idea that Nicholas was controlled by his German-born wife Alexandra and the self-proclaimed holy man Rasputin. Nicholas and Alexandra refused to listen. In December 1916, Michael's cousin Dmitri and four friends killed Rasputin. Michael learned of the murder at Brasovo, where he was spending Christmas. On December 28, there was a failed attempt to kill Alexandra. The attacker was caught and executed the next day. The Duma President Mikhail Rodzianko, Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna, and British ambassador Buchanan all called for Alexandra to lose her influence. But Nicholas still refused their advice. Plots and rumors against Nicholas and Alexandra continued to grow.

In January 1917, Michael returned to the front to hand over command of his corps. From January 29, he was Inspector-General of Cavalry stationed at Gatchina. General Aleksei Brusilov, Michael's commander, begged him to tell the Tsar about "the need for immediate and strong changes." But Michael warned him, "I have no influence... My brother has time and time again had warnings and pleas of this kind from every side." Brusilov wrote in his memoirs that Michael "was an absolutely honest and fair man, taking no sides and getting involved in no secret plans... he avoided all kinds of gossip. As a soldier, he was an excellent leader and a humble and hardworking person."

Through February, Grand Duke Alexander, Duma President Rodzianko, and Michael pressured Nicholas and Alexandra to give in to popular demands. Public unrest grew. On February 27, soldiers in Petrograd joined demonstrators. Parts of the military rebelled, and prisoners were freed. Nicholas, who was at army headquarters, closed the Duma. But the deputies refused to leave. Instead, they set up their own rival government. After talking to Rodzianko, Michael advised Nicholas to fire his ministers. He suggested setting up a new government led by Georgy Lvov, the leader of the majority party in the Duma. General Mikhail Alekseyev, Nicholas's chief of staff, supported this advice. Nicholas rejected the idea and gave useless orders for troops to move on Petrograd.

The Revolution and Nicholas's Abdication

On the night of February 27–28, 1917, Michael tried to return to Gatchina from Petrograd. He had been meeting with Rodzianko and Nikolai Golitsyn. He had also sent a telegram to the Tsar. But revolutionary patrols and gunfire stopped him. Revolutionaries were on the streets, arresting people connected to the old government. Michael managed to reach the Winter Palace. He ordered the guards to move to the Admiralty. This building was safer and in a better position. It was also less politically charged. Michael himself hid in the apartment of a friend, Princess Putyatina. In nearby apartments, the Tsar's Chamberlain and the Procurator of the Holy Synod were arrested by revolutionaries. In the house next door, General Baron Staekelberg was killed when a mob stormed his house.

On March 1, Rodzianko sent guards to Putyatina's apartment to keep Michael safe. Michael signed a document written by Rodzianko and Grand Duke Paul. It suggested creating a constitutional monarchy. But the newly formed Petrograd Soviet rejected the document, making it useless. Calls for the Tsar to give up his throne had become more important.

On the afternoon of 15 March [O.S. 2 March] 1917, Emperor Nicholas II gave up his throne. He was pressured by generals and Duma representatives. He decided to give it to his son, Alexei, with Michael as Regent. Later that evening, he changed his mind. Alexei was very ill with hemophilia. Nicholas feared that if Alexei was emperor, he would be separated from his parents. In a second document, signed at 11:40 p.m. but dated 3:00 p.m., Nicholas II stated:

We have judged it right to give up the Throne of the Russian State and to lay down the Supreme Power. Not wishing to be parted from Our Beloved Son, We hand over Our Succession to Our Brother the Grand Duke Michael Aleksandrovich and Bless Him on his accession to the Throne.

By early morning, Michael was announced as "Emperor Michael II" to Russian troops and in cities across Russia. But his becoming emperor was not welcomed by everyone. Some army units cheered and swore loyalty to the new emperor. Others did not care. The newly formed Provisional Government had not agreed to Michael becoming emperor. When Michael woke up that morning, he found out his brother had given up the throne to him. Nicholas had not told him before. He also learned that a group from the Duma would visit him in a few hours. The meeting with Duma President Rodzianko, the new Prime Minister Prince Lvov, and other ministers, including Pavel Milyukov and Alexander Kerensky, lasted all morning. Putyatina provided lunch. In the afternoon, two lawyers were called to draft a statement for Michael to sign. The legal situation was complicated. It was unclear if the government was legitimate, if Nicholas had the right to remove his son from the succession, or if Michael was truly emperor. After more discussion, they agreed on a statement of conditional acceptance. In it, Michael agreed to the will of the people. He recognized the Provisional Government as the acting government. But he neither gave up nor refused the throne. He wrote:

Inspired, in common with the whole people, by the belief that the welfare of our country must be set above everything else, I have taken the firm decision to assume the supreme power only if and when our great people, having elected by universal suffrage a Constituent Assembly to determine the form of government and lay down the fundamental law of the new Russian State, invest me with such power.

Calling upon them the blessing of God, I therefore request all the citizens of the Russian Empire to submit to the Provisional Government, established and invested with full authority by the Duma, until such time as the Constituent Assembly, elected within the shortest possible time by universal, direct, equal and secret suffrage, shall manifest the will of the people by deciding upon the new form of government.

People like Kerensky and French ambassador Maurice Paléologue saw Michael's action as noble and patriotic. But Nicholas was upset that Michael had "given in to the Constituent Assembly." He called the statement "rubbish."

Monarchists hoped Michael might take the throne after the Constituent Assembly was elected. But events moved too fast. His giving up the throne, even if conditional, marked the end of the Tsarist rule in Russia. The Provisional Government had little real power. The Petrograd Soviet held the true power.

Arrest and Imprisonment

Michael returned to Gatchina. He was not allowed to go back to his army unit or travel outside the Petrograd area. On April 5, 1917, he was discharged from military service. By July, Prince Lvov had resigned as Prime Minister. Alexander Kerensky replaced him. Kerensky ordered former Emperor Nicholas to be moved from Petrograd to Tobolsk in the Urals. He said it was "some remote place, some quiet corner, where they would attract less attention." The night before Nicholas left, Kerensky allowed Michael to visit him. Kerensky stayed during the meeting. The brothers exchanged polite but awkward greetings. It was the last time they saw each other.

On August 21, 1917, guards surrounded the villa where Michael lived with Natalia. By Kerensky's orders, they were both under house arrest. Nicholas Johnson, Michael's secretary since 1912, was also arrested. A week later, they were moved to an apartment in Petrograd. Michael's stomach problems got worse. With help from British ambassador Buchanan and foreign minister Mikhail Tereshchenko, they were moved back to Gatchina in early September. Tereshchenko told Buchanan that the Dowager Empress would be allowed to leave the country for Britain if she wished. Michael would follow later. However, the British were not willing to accept any Russian Grand Duke. They feared it would cause a negative public reaction in Britain, where there was little sympathy for the Romanovs.

On September 1, 1917, Kerensky declared Russia a republic. Michael wrote in his diary: "We woke up this morning to hear Russia declared a Republic. What does it matter which form the government will be as long as there is order and justice?" Two weeks later, Michael's house arrest was lifted. Kerensky had armed the Bolsheviks after a power struggle. In October, there was a second revolution as the Bolsheviks took power from Kerensky. With a travel permit from a former colleague, Michael planned to move his family to safer Finland. They packed valuables and got ready to move. But Bolshevik supporters saw their preparations. They were placed under house arrest again. The last of Michael's cars were seized by the Bolsheviks.

The house arrest was lifted again in November. The Constituent Assembly was elected and met in January 1918. Even though they were the minority party, the Bolsheviks dissolved it. On March 3, 1918, the Bolshevik government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This treaty gave away large areas of the former Russian Empire to Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. On March 7, 1918, Michael and his secretary Johnson were arrested again. This was by order of Moisei Uritsky, the head of the Petrograd secret police. They were imprisoned at the Bolshevik headquarters.

Life in Perm and Death

On March 11, 1918, Uritsky sent Michael and Johnson to Perm. This city was a thousand miles to the east. The journey by freight train, without windows or heat, took eight days. At first, Michael stayed in a hotel. But two days after arriving, he was jailed by the local Soviet. Natalia asked the officials in Petrograd for his release. On April 9, 1918, he was set free within Perm. He moved into the best room in the best hotel in Perm. Johnson and two servants, Vasily Chelyshev and Borunov, were with him. Natalia feared for George's safety. In March 1918, she arranged for him to be secretly taken out of Russia by his governess, Margaret Neame. Danish diplomats and the Putyatins helped.

In May, Natalia was given permission to join Michael. She arrived in Perm before Orthodox Easter. They spent about a week together. Meanwhile, as part of the truce between the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers, prisoners-of-war from Austria-Hungary were being sent out of Russia. Czech troops were spread along the Trans-Siberian Railway. They were on their way to Vladivostok to take a ship. However, the Czechs were not going home to fight for Austria. They wanted to fight for their own independent homeland. The Germans demanded that the Bolsheviks disarm the Czechs. But the Czechs fought back. They took control of the railway and joined forces with Russians fighting against the Bolsheviks. They advanced west toward Perm. With the Czechs approaching, Michael and Natalia feared she would get trapped there. So, on May 18, she left sadly. By early June, Michael was again ill with stomach problems.

On June 12, 1918, Gavril Myasnikov, the leader of the local secret police, planned to murder Michael. Myasnikov gathered a team of four men. They were all former prisoners of the Tsar. Using a fake order, the four men entered Michael's hotel at 11:45 p.m. At first, Michael refused to go with them. He wanted to speak with the local police chief. He also said he was ill. But his protests were useless, and he got dressed. Johnson insisted on going with him. The four men and their two prisoners got into two horse-drawn carriages.

They drove out of town into the forest near Motovilikha. When Michael asked where they were going, he was told they were going to a remote railway crossing to catch a train. By now it was the early hours of June 13. They all got out of the carriages in the middle of the woods. Both Michael and Johnson were killed.

They were buried. Anything valuable was stolen. Their clothes were taken back to Perm. After being shown to Myasnikov as proof of the murders, the clothes were burned. The Ural Regional Soviet, led by Alexander Beloborodov, approved the killing. Lenin also approved it. Michael was the first of the Romanovs to be killed by the Bolsheviks. But he was not the last. Neither Michael's nor Johnson's remains have been found.

The Perm authorities spread a made-up story. They said Michael was taken by unknown men and had disappeared. Chelyshev and Borunov were arrested. Shortly before his own arrest, Colonel Peter Znamerovsky, a former Imperial army officer also sent to Perm, managed to send Natalia a short telegram saying Michael had disappeared. Znamerovsky, Chelyshev, and Borunov were all killed by the Perm Bolsheviks. Soviet false information about Michael's disappearance led to rumors that he had escaped and was leading a successful fight against the Bolsheviks. Hoping Michael would ally with Germany, the Germans helped Natalia and her daughter escape to Kiev. On the collapse of the Germans in November 1918, Natalia fled to the coast. She and her daughter were taken away by the British Royal Navy.

On June 8, 2009, Michael and Johnson were officially cleared of any wrongdoing. Russian State Prosecutors said, "The analysis of the archive material shows that these individuals were subject to repression through arrest, exile and scrutiny... without being charged of committing concrete class and social-related crimes."

Michael's son George, Count Brasov, died in a car crash in 1931, shortly before his 21st birthday. Natalia died without money in a Parisian charity hospital in 1952. His stepdaughter Natalia Mamontova married three times. She wrote a book about her life called Step-Daughter of Imperial Russia, published in 1940.

Military Roles and Commands

Michael held several important military positions:

Russian Military Positions

- Life-Guards Horse Artillery Brigade – lieutenant, 1898

- Life-Guards Her Imperial Majesty Empress Maria Feodorovna's Cuirassier Regiment – captain and squadron commander, 1902

- 17th Hussar Chernigovskii HIH Grand Princess Elizavet Feodorovna Hussars – colonel, commanding, 1910

- Life-Guards Her Imperial Majesty Empress Maria Feodorovna's Chevalier Guards Regiment – colonel, commanding, 1912

- Caucasian Native Mounted Division – major-general, commanding, 1914

- Second Cavalry Corps, Seventh Army – lieutenant-general, 1916

- Inspector-General of Cavalry, 1917

Foreign Military Positions

- Ulanen-Regiment Kaiser Alexander III von Rußland (Westpreußisches) Nr.1, Prussian/Imperial German Army – colonel and regimental chief, December 1901

- à la suite Imperial German Navy

Honors and Awards

Michael received many honors from Russia and other countries:

Russian Honors

- Knight of St. Andrew, October 12, 1878

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, October 12, 1878

- Knight of the White Eagle, October 12, 1878

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class, October 12, 1878

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class, October 12, 1878

- Alexander III Commemorative Medal, March 17, 1896

- Nicholas II Coronation Medal, May 26, 1896

- Knight of St. Vladimir, 4th Class (civil), November 22, 1905; with Swords (for actions during the Brusilov Offensive), 1916

- Knight of St. George, 4th Class (for actions in the Carpathian Mountains), January 1915

- St. George Sword, June 27, 1915

Foreign Honors

Denmark:

Denmark:

- Commemorative Medal for the Golden Wedding of King Christian IX and Queen Louise, May 26, 1892

- Knight of the Elephant, August 6, 1897

- Cross of Honour of the Order of the Dannebrog, September 27, 1899

Emirate of Bukhara:

Emirate of Bukhara:

- Order of the Golden Star of Bukhara, 1st Class, January 1, 1893

- Order of the Crown of Bukhara, in Diamonds, May 25, 1896

- Order of the Sun of Alexander, in Diamonds, May 19, 1898

Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, July 16, 1894

Mecklenburg: Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, July 16, 1894 Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, November 26, 1894

Grand Duchy of Hesse: Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, November 26, 1894 Principality of Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I, May 17, 1896

Principality of Montenegro: Grand Cross of the Order of Prince Danilo I, May 17, 1896 Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, May 25, 1896

Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach: Grand Cross of the White Falcon, May 25, 1896

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, May 15, 1897

Austria-Hungary: Grand Cross of the Royal Hungarian Order of St. Stephen, May 15, 1897 Siam: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, July 4, 1897

Siam: Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, July 4, 1897 Kingdom of Romania: Grand Cross of the Star of Romania, July 8, 1898

Kingdom of Romania: Grand Cross of the Star of Romania, July 8, 1898

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, November 9, 1899

Ernestine duchies: Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, November 9, 1899 Empire of Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, September 8, 1900

Empire of Japan: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum, September 8, 1900 Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer, September 22, 1900

Kingdom of Greece: Grand Cross of the Redeemer, September 22, 1900 Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, January 16, 1901

Kingdom of Italy: Knight of the Annunciation, January 16, 1901 United Kingdom:

United Kingdom:

- Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath (civil), February 15, 1901

- Stranger Knight Companion of the Garter, July 15, 1902

- Commemorative Medal for the Coronation of King Edward VII, August 19, 1902

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, April 14, 1901

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour, April 14, 1901 Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Sash of the Two Orders, April 27, 1901

Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Sash of the Two Orders, April 27, 1901 Kingdom of Prussia:

Kingdom of Prussia:

- Knight of the Black Eagle, December 15, 1901

- Grand Commander's Cross of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, May 23, 1905

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, December 26, 1901

Spain: Knight of the Golden Fleece, December 26, 1901 Persian Empire: Order of the August Portrait, in Diamonds, February 12, 1902

Persian Empire: Order of the August Portrait, in Diamonds, February 12, 1902 Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, June 26, 1902

Oldenburg: Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, June 26, 1902 Norway:

Norway:

- Silver Commemorative Medal for the Coronation of King Haakon VII, June 6, 1906

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, with Collar, June 22, 1906

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, May 12, 1908

Sweden: Knight of the Seraphim, May 12, 1908

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Románov para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Románov para niños