History of Australia (1851–1900) facts for kids

This article explores the exciting history of Australia between 1851 and 1900. This was a time of big changes for both the Indigenous people and the European settlers. It was also the 50 years leading up to when Australia became a united country in 1901.

Contents

Gold Rushes: Australia's Golden Age

The discovery of gold in 1851 completely changed Australia. It started near Bathurst in New South Wales, then spread to the new colony of Victoria. These gold rushes happened after a period of tough economic times around the world. Because of this, many people from Britain and Ireland moved to New South Wales and Victoria in the 1850s. People also came from Europe, North America, and China.

The gold rush officially began in 1851. This was when Edward Hargraves announced he had found a lot of gold near Bathurst. At that time, New South Wales had about 200,000 people. Most lived near Sydney, with others spread out along the coast. In 1836, the new colony of South Australia had been created, separate from New South Wales.

The gold rushes of the 1850s brought many new settlers. Most went to the richest gold fields like Ballarat and Bendigo. These areas were in the Port Phillip District, which became the colony of Victoria in 1851. Victoria quickly grew to have more people than New South Wales. Its capital, Melbourne, became bigger than Sydney for a while.

However, New South Wales also attracted many gold seekers. By 1857, it had over 300,000 people. Inland towns like Bathurst, Goulburn, Orange, and Young grew quickly. Gold brought great wealth but also new social challenges. Many different groups of migrants came to New South Wales for the first time.

Challenges and New Ideas from Gold Rush Migrants

In 1861, Young was the site of a famous anti-Chinese miner riot. The official Riot Act was read to the miners there. This was the only time it was officially read in New South Wales history. Despite some tensions, the new migrants also brought fresh ideas from Europe and North America. For example, Norwegians introduced skiing in Australia to the hills near the gold rush town of Kiandra around 1861. A famous Australian poet, Henry Lawson, was born to a Norwegian miner in 1867 at the Grenfell goldfields.

In 1858, a new gold rush started in the far north. This led to Queensland becoming a new colony in 1859. New South Wales then got its current borders. The Northern Territory stayed part of New South Wales until 1863, when it was given to South Australia. The fast growth of Victoria and Queensland marked the real beginning of New South Wales as a separate area.

Rivalry Between Colonies

There was strong competition between New South Wales and Victoria in the second half of the 19th century. The two colonies developed in different ways. Once the easy gold ran out around 1860, Victoria used its extra workers in factories. It protected these factories with high taxes on imported goods. Victoria became a strong supporter of protecting local industries and new ideas.

New South Wales was less changed by the gold rushes. It remained more traditional, with wealthy landowners and Sydney businesses still holding much power. New South Wales, focused on trade and exports, continued to support free trade.

Gold made some people very rich very quickly. Some of Australia's oldest wealthy families started their fortunes during this time. But gold also created jobs and a good life for many more. Within a few years, these new settlers outnumbered the convicts and former convicts. They began to demand things like trial by jury, elected government, and a free press. These were all symbols of freedom and democracy.

Eureka Stockade: A Fight for Fairness

The Eureka Stockade in 1854 was an armed protest by miners in Victoria. It helped bring about important changes for democracy. The rebellion happened because miners were unhappy about government mining licenses. Miners had to pay for these licenses even if they didn't find any gold. Less successful miners found it hard to pay. Official corruption was also a problem.

In November 1854, thousands of miners gathered to demand an end to the license fee and the right to vote for all men. They formed a Reform League. On November 30, miners publicly burned their licenses and marched to the Eureka Diggings. There, they built a fort, or "stockade." Led by Peter Lalor, 500 men swore an oath under a flag with the Southern Cross and prepared to defend their stockade.

On December 3, colonial troops attacked the stockade. A short, fierce battle followed, lasting about twenty minutes. Twenty-two miners and five soldiers were killed. Thirteen miners who were put on trial were all found innocent. The next year, the government agreed to the rebels' demands. In the 1855 elections, Peter Lalor became the first Member of the Legislative Council for Ballarat.

In 1855, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania (which used to be called Van Diemen's Land) gained full responsible government. This meant they had parliaments with two houses, and the lower houses were fully elected. The upper houses were still mostly made up of government choices and landowners. These landowners worried that the new democratic ideas might threaten their large sheep farms. Their fears were partly true. New laws in the 1860s, like the Robertson Land Acts of 1861, slowly began to break up the power of these large landowners in settled areas.

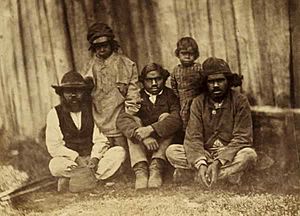

Impact on Aboriginal Australians

The arrival of European diseases was a disaster for Aboriginal Australians. Between the first European contact and the early 1900s, the Aboriginal population dropped from an estimated 500,000 to about 50,000. Diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza were major killers. Even chickenpox was deadly for people who had not built up resistance over thousands of years like Europeans had.

The Bushrangers: Outlaws of the Bush

Bushrangers were originally runaway convicts in the early days of British settlement in Australia. They knew how to survive in the Australian bush and used it to hide from the police. Later, the term "bushranger" meant people who chose a life of "robbery under arms," using the bush as their base. They were similar to British "highwaymen" or American "Old West outlaws." Their crimes often included robbing small-town banks or stagecoaches.

More than 3,000 bushrangers are thought to have roamed the Australian countryside. This started with the escaped convicts and ended after Ned Kelly's final stand in Glenrowan.

Famous Bushrangers

[[Bold Jack Donahue]] is known as the last convict bushranger. Newspapers reported him causing trouble on the road between Sydney and Windsor around 1827. In the 1830s, he was the most famous bushranger in the colony. Donahue, leading a group of escaped convicts, became a key figure in Australian stories as the Wild Colonial Boy.

Bushranging was common on the mainland. But Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) had the most violent outbreaks of convict bushrangers. Hundreds of convicts were loose in the bush. Farms were left empty, and strict military rule was put in place. The Indigenous outlaw Musquito went against colonial law and led attacks on settlers.

The busiest time for bushrangers was during the Gold Rush years of the 1850s and 1860s.

There was a lot of bushranging in the Lachlan Valley, near Forbes, Yass, and Cowra in New South Wales. Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert, and Ben Hall led the most well-known gangs of this time. Other active bushrangers included Dan Morgan, who was based near the Murray River, and Captain Thunderbolt, who was killed near Uralla.

The End of the Bushrangers

As more people settled the land, police became better at their jobs. Improvements in train travel and communication, like the telegraph, made it harder for bushrangers to escape.

Among the last bushrangers was the Kelly Gang, led by Ned Kelly. They were captured at Glenrowan in 1880, two years after they were declared outlaws. Kelly was born in Victoria. His father was an Irish convict. As a young man, Ned often had problems with the Victoria Police. After an incident at his home in 1878, police searched for him in the bush. After he killed three policemen, the colony declared Kelly and his gang wanted outlaws.

A final violent fight with police happened at Glenrowan on June 28, 1880. Kelly, wearing homemade metal armour and a helmet, was captured and sent to jail. He was hanged for murder at Old Melbourne Gaol in November 1880. His bravery and fame made him a very important figure in Australian history, stories, art, and films.

Some bushrangers, especially Ned Kelly, saw themselves as political rebels. Kelly's views, shared in his Jerilderie Letter and during his last raid, show how Australians felt mixed emotions about bushrangers.

Exploring Australia's Vast Interior

During this period, European explorers made their last big, often difficult, and sometimes sad journeys into Australia's inland. Some expeditions were supported by the government, while others were paid for by private investors. By 1850, large parts of the inland were still unknown to Europeans. Brave explorers like Edmund Kennedy and the German scientist Ludwig Leichhardt had died trying to map these areas in the 1840s. But explorers still wanted to find new lands for farming or answer scientific questions. Surveyors also acted as explorers. The colonies sent out expeditions to find the best routes for communication lines. The size of these expeditions varied greatly. Some were small groups of two or three people, while others were large, well-equipped teams. These teams were led by gentlemen explorers and helped by blacksmiths, carpenters, workers, and Aboriginal guides. They traveled with horses, camels, or bullocks.

Famous Expeditions and Discoveries

In 1860, the unlucky Burke and Wills expedition tried to cross the continent from south to north, from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Burke and Wills were not good at bushcraft and didn't want to learn from the local Aboriginal people. They died in 1861. They had returned from the Gulf to their meeting point at Coopers Creek, only to find that the rest of their group had left just hours before. Even though it was an amazing feat of navigation, the expedition was a disaster in how it was organized. It still fascinates Australians today.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart successfully crossed Central Australia from south to north. His journey mapped out the path that the Australian Overland Telegraph Line later followed.

Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872. This was possible because the Australian Overland Telegraph Line was being built. In separate journeys, Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. While exploring in 1872, Giles saw Kata Tjuta from near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga. The next year, Gosse saw Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, after Sir Henry Ayers, the Chief Secretary of South Australia. These dry desert lands of Central Australia disappointed Europeans who thought they were not good for farming. But later, they became important symbols of Australia.

Impact on Indigenous People from European Expansion

The steady movement of European explorers and farmers onto Aboriginal lands was met with different reactions. These ranged from friendly or curious to fearful or violent. Often, early European expeditions only succeeded because Aboriginal guides or negotiators helped them. Or they got advice from tribes they met along the way.

However, the arrival of Europeans greatly changed Aboriginal society. According to historian Geoffrey Blainey, during the colonial period in Australia: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation."

Farmers often set up their homes beyond where Europeans had settled. Competition for water and land between Indigenous people and cattlemen often led to conflict. This was especially true in the dry inland areas. In later years, Aboriginal men began working as skilled stockmen on cattle stations in the outback.

Christian missionaries tried to convert Aboriginal people. Famous Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson (born 1965) grew up at a Lutheran mission in Cape York. He has written that Christian missions throughout Australia's colonial history "provided a haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier while at the same time facilitating colonisation."

Some studies of Aboriginal culture were also done during this time. A very important work on Indigenous Australia was done by Walter Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen. Their famous study, The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899), became known around the world. It gives a valuable look at an Indigenous Australian society in the 19th century. Around this time, Aboriginal welfare advocate and anthropologist Daisy Bates started her work among the Aborigines. She began after reading a report in The Times about terrible acts against Aboriginal people in north-west Australia. Bates came to fear that the Aboriginal race was going to disappear.

Once Europeans controlled Aboriginal land, the local Aboriginal people who had not been affected by disease or conflict were usually moved to reserves or missions. Others settled near white communities or worked as farmhands for white farmers. Some married or had children with Europeans. European food, diseases, and alcohol had a bad effect on many Aboriginal people. Only a few remained living traditional lives, untouched by Europeans, by the end of the 19th century. These were mainly in the far North and in the Centralian deserts.

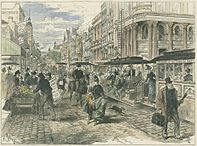

Economic Growth, Hard Times, and Workers' Rights

The fast economic growth after the gold rushes led to a time of wealth that lasted forty years. This peaked with a huge land boom in the 1880s. Melbourne, in particular, grew very quickly. For a short time, it was Australia's largest city and the second-largest city in the British Empire. Then, Sydney's population grew rapidly in the early 1900s and overtook it. The grand Victorian buildings in both cities are a lasting reminder of this wealthy period. Stonemasons in Melbourne were the first organized workers in the Australian labour movement and in the world to win an eight-hour day in 1856.

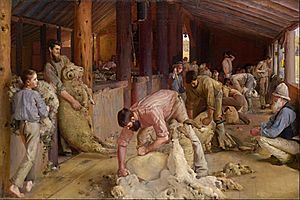

The Melbourne Trades Hall opened in 1859. Workers' councils and Trades Halls opened in all cities and most regional towns over the next forty years. In the 1880s, trade unions grew among shearers, miners, and stevedores (wharf workers). Soon, they covered almost all manual labor jobs. A shortage of workers meant high wages for skilled workers. Their unions demanded and got an eight-hour day and other benefits that were unheard of in Europe.

"Working Man's Paradise" and Challenges

Australia gained a reputation as "the working man's paradise." Some employers tried to pay less by bringing in Chinese workers. This led to a reaction that caused all the colonies to limit Chinese and other Asian immigration. This was the start of the White Australia Policy. This "Australian agreement," based on central wage setting, some government help for industries, and White Australia, continued for many years. It slowly changed in the second half of the 20th century.

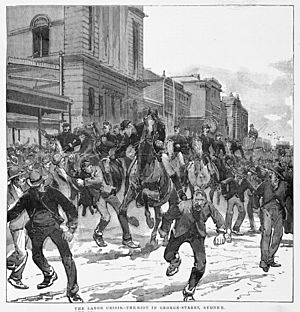

The great economic boom could not last forever. In 1891, it ended with a major economic downturn that lasted a decade. This caused high unemployment and ruined many businesses. Employers responded by lowering wages. The unions reacted with a series of strikes. These included the difficult and long 1890 Australian maritime dispute and the 1891 and 1894 shearers' strikes.

The colonial governments, mostly made up of politicians the unions had seen as friends, turned sharply against the workers. There were many violent clashes, especially in the farming areas of Queensland. The unions reacted to these defeats and what they saw as betrayals by forming their own political parties in their colonies. These were the early versions of the Australian Labor Party. These parties quickly found success. In 1899, Queensland had the world's first Labor Party government, the Dawson Government, which held office for six days.

The worker struggles of the 1890s created a new kind of Australian spirit and nationalism. This was shown in the Sydney-based magazine The Bulletin, under its famous editor J. F. Archibald. Writers like A B "Banjo" Paterson, Henry Lawson, and later Vance and Nettie Palmer and Mary Gilmour promoted ideas of socialism, republicanism, and Australian independence. This new Australian awareness also led to strong racism against Chinese, Japanese, and Indian immigrants. Attitudes towards Indigenous Australians during this time varied. Some were openly hostile, while others were more like a "smoothing the pillow" policy. This policy aimed to "civilise" the last remaining Indigenous people, who were thought to be a dying race.

Images for kids

-

South Australian suffragist Catherine Helen Spence (1825–1910). In 1895, women in South Australia were among the first in the world to get the right to vote and the first to be able to run for parliament.

-

Sir Henry Parkes (1815–1896), known as the 'Father of Federation'.

-

The celebration of the Federation of Australia at the Sydney Town Hall in 1900.

-

Cricket being played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in the 1860s.

-

The Australian Native, by Tom Roberts, 1888. Distinctly Australian painting began with the Heidelberg School in the 1880s–90s.

-

Writer Henry Lawson (right) with J. F. Archibald, who co-founded The Bulletin.

-

Saint Mary MacKillop (1842–1909).

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |