History of Melbourne facts for kids

The history of Melbourne tells the story of how this big city in Victoria grew from a small settlement into a busy modern centre for business and money. Today, Melbourne is Australia's second-largest city.

Contents

- Ancient History: Before Europeans Arrived

- Early European Explorers and Settlements

- Founding the Town of Melbourne

- Early Growth and Challenges

- The Gold Rush Era: 1850s Boom

- Expansion in the 1880s and 1890s

- The 1891 Economic Crash

- "Australia's Capital": 1901-1927

- Between the World Wars

- World War II and After

- Post-World War II Growth

- The 2000s

- The 2010s and 2020s

- See also

Ancient History: Before Europeans Arrived

The land where Melbourne now stands, around Port Phillip and the Yarra River, was once home to the Kulin nation. This was a group of several Aboriginal language groups. Their ancestors had lived here for a very long time, possibly 31,000 to 40,000 years!

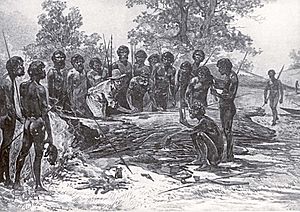

When Europeans first arrived, there were about 20,000 Indigenous people in what is now Victoria. Three main groups lived around Melbourne: the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung (Bunurong), and Wathaurong.

This area was a special meeting place for the Kulin clans. It had plenty of food, water, and a safe bay for gatherings and yearly events. The Kulin people were good at fishing, hunting, and gathering food from the rich lands around Port Phillip.

Today, many Aboriginal people in Melbourne come from groups across Victoria and Australia. But some still identify as Wurundjeri and Bunurong, who are the original people of the Melbourne area. Even though there are few obvious signs of their past, many places hold deep cultural and spiritual meaning for them.

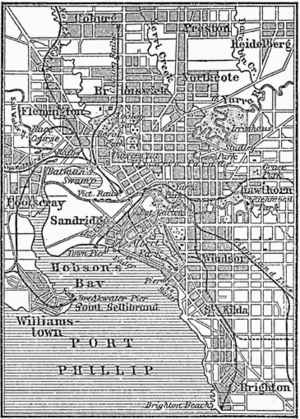

In 2021, the boundaries between the Wurundjeri and Bunurong lands were officially agreed upon. This line runs across the city. The CBD, Richmond, and Hawthorn are on Wurundjeri land. Albert Park, St Kilda, and Caulfield are on Bunurong land.

Early European Explorers and Settlements

In 1797, George Bass was the first European to sail into what is now called Bass Strait. This is the water between mainland Australia and Tasmania (then called Van Diemen's Land). He sailed along the coast of the Gippsland region of Victoria.

Later, in 1802, John Murray and then Matthew Flinders explored Port Phillip. In 1803, Charles Grimes was sent to map the area. He landed at Frankston and met about thirty local Aboriginal people.

Grimes also explored the Yarra River and Maribyrnong River. One of his team, James Flemming, noted that the soil was good. He thought the Yarra River area would be the best place for a settlement. However, Grimes reported that Port Phillip was not a good spot for a colony.

Despite this, in 1803, the British Governor of New South Wales, Captain Philip Gidley King, worried that the French might take over the Bass Strait area. So, he sent Colonel David Collins with 300 convicts to start a settlement at Port Phillip.

Collins arrived at Sorrento in October 1803. But he found there wasn't enough fresh water. In May 1804, Collins moved the settlement to Tasmania, where he founded Hobart. The northern shores of Bass Strait were then left mostly to whalers and sealers. One of the convicts at Sorrento was a boy named John Pascoe Fawkner, who would later return to settle in Melbourne.

In 1824, Hamilton Hume and William Hovell travelled overland from New South Wales. They didn't find Western Port, but instead reached Corio Bay. There, they found excellent land for grazing animals.

It was ten more years before Edward Henty, a farmer from Tasmania, started an illegal sheep farm at Portland in 1834.

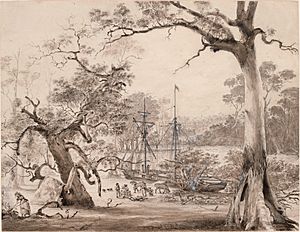

John Batman, another successful farmer from Tasmania, also wanted more grazing land. He sailed into Port Phillip Bay on May 29, 1835. He explored the areas around Corio Bay (near Geelong) and the Yarra and Maribyrnong rivers. He explored a large area where Melbourne's northern suburbs are today.

Founding the Town of Melbourne

On June 6, 1835, John Batman, as part of a business group called the Port Phillip Association, signed a treaty with eight Wurundjeri elders. He claimed to buy about 600,000 acres of land around Melbourne and another 100,000 acres near Geelong.

On June 8, he wrote in his journal: "So the boat went up the large river... and... I am glad to state about six miles up found the River all good water and very deep. This will be the place for a village." This last sentence became famous as the "founding charter" of Melbourne.

Batman went back to Launceston to plan a big trip to settle on the Yarra. But John Pascoe Fawkner, now a businessman, had the same idea. Fawkner bought a ship, the schooner Enterprize, which sailed on August 4 with settlers. When Batman's group reached the Yarra on September 2, they were surprised to find Fawkner's people already there!

The two groups decided there was enough land for everyone. When Fawkner arrived on October 16 with more settlers, they agreed to share the land. Both Batman and Fawkner settled in the new town.

The New South Wales government, which ruled eastern Australia at the time, cancelled Batman's treaty on August 26, 1835. This meant the settlers were technically on Crown land without permission. However, the government eventually accepted that the settlers were already there and allowed the town to stay.

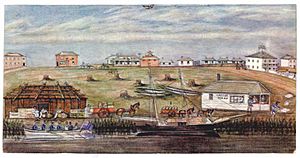

In September 1836, Governor Richard Bourke created the Port Phillip District of New South Wales. He appointed Captain William Lonsdale as the police magistrate and chief government agent. Lonsdale arrived on September 29, 1836, and officially announced the new settlement.

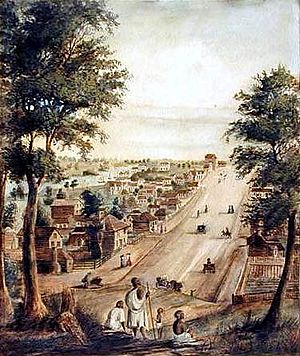

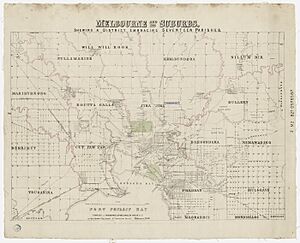

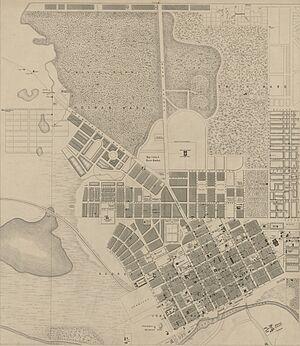

Bourke also asked Robert Hoddle to create the first plan for the town, which was finished on March 25, 1837. This plan is known as the Hoddle Grid. Bourke visited Port Phillip in March 1837. He approved Lonsdale's choice for the town site and named it Melbourne on April 10, 1837. It was named after the British Prime Minister, William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne. Before its official name, the town had several temporary names like Batmania and Bearbrass.

Charles La Trobe became the Superintendent of the district in 1839. He was a talented man who helped lay the groundwork for Melbourne to become a real city. La Trobe's most important contribution was setting aside large areas as public parks. These include the Treasury Gardens, Carlton Gardens, Flagstaff Gardens, Royal Park, and the Royal Botanic Gardens.

By 1841, the population of Port Phillip was 11,738. On August 12, 1842, Melbourne was officially made a "town." On June 25, 1847, Queen Victoria declared it the City of Melbourne.

Early Growth and Challenges

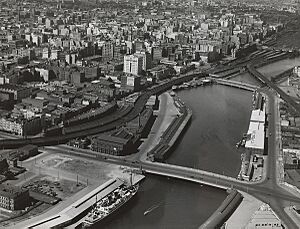

Melbourne started as a group of tents and huts along the Yarra River. People used the river for bathing and drinking. By the 1850s, the river became very polluted, causing a typhoid fever outbreak that led to many deaths. Even after the first public baths opened in 1860, people continued to use the river water.

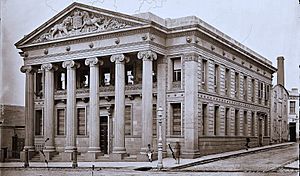

Most of early Melbourne was built from timber. Very few buildings from this time still exist. Two exceptions are St James Old Cathedral (1839) and St Francis Catholic Church (1841).

Suburban areas began to develop. The first land sales in St Kilda happened in 1842, and wealthy people started building houses by the sea. A port also grew at Williamstown. In 1844, a wooden bridge was built across the Yarra River at Swanston Street, replacing private ferries. In 1850, a government-built stone bridge replaced the wooden one.

When Europeans arrived, the local Indigenous people suffered greatly from new diseases and mistreatment. There were also conflicts, like the Battle of Yering in 1840. In 1863, the surviving Wurundjeri and other Woiwurrung speakers were given land at Coranderrk Station, near Healesville, and were forced to move there.

In July 1851, Victoria became a separate colony, and La Trobe became its first Lieutenant-Governor. In 1851, the white population of the Port Phillip District was only 77,000, with 23,000 people living in Melbourne. Melbourne was already a key centre for Australia's wool trade.

A few months after Victoria became a separate colony, gold was found in several places, especially at Ballarat and Bendigo. The gold rush completely changed Victoria, and especially Melbourne. Many stone and brick buildings were built during the land boom of the 1850s.

The Gold Rush Era: 1850s Boom

The discovery of gold brought a huge number of people to Victoria, mostly arriving by sea in Melbourne. The city's population doubled in just one year. In 1852, 75,000 people arrived. This, plus a high birthrate, led to very fast population growth. At the same time, Aboriginal populations in inland Victoria were rapidly displaced.

In 1853, work began on the Yan Yean Reservoir to supply water to Melbourne. Piped water started flowing in 1857. Victoria's population reached 400,000 in 1857 and 500,000 in 1860. As the easily found gold ran out, many miners moved to Melbourne or became unemployed in cities like Ballarat. This led to social unrest, with people demanding that rural land be opened up for small farms.

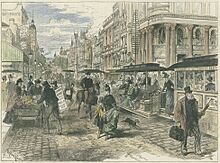

The fast population growth and the huge wealth from the goldfields caused a boom that lasted for forty years. This time is known as "marvellous Melbourne." The city grew east and north over the flat grasslands, and south along the eastern shore of Port Phillip. Rich new suburbs like South Yarra, Toorak, Kew, and Malvern appeared. Working-class people settled in Richmond, Collingwood, and Fitzroy.

Many educated gold seekers from England arrived, leading to a quick growth of schools, churches, libraries, and art galleries. Australia's first telegraph line was built between Melbourne and Williamstown in 1853. The first railway in Australia was built in Melbourne in 1854, connecting the city to Port Melbourne.

The University of Melbourne was founded in 1855, and the State Library of Victoria in 1856. The foundation stone for St Patrick's Catholic Cathedral was laid in 1858. The Philosophical Institute of Victoria became the Royal Society of Victoria in 1859.

A Melbourne Town Council was created in 1847. Other suburbs also gained town status with their own councils. In December 1854, unhappiness with the goldfield licensing system led to the Eureka Stockade uprising. This was one of only two armed rebellions in Australian history.

In November 1856, Victoria got its own constitution and a Parliament. For Melbourne, this meant the building of the grand Parliament House, Melbourne. Construction started in December 1855 and continued until 1929, though it was never fully completed to the original design.

The boom, fueled by gold and wool, continued through the 1860s and 70s. Victoria had a shortage of workers, which pushed wages up to be the highest in the world. Victoria was known as "the working man's paradise." The Stonemasons Union won the eight-hour day in 1856 and built the large Melbourne Trades Hall in Carlton.

Expansion in the 1880s and 1890s

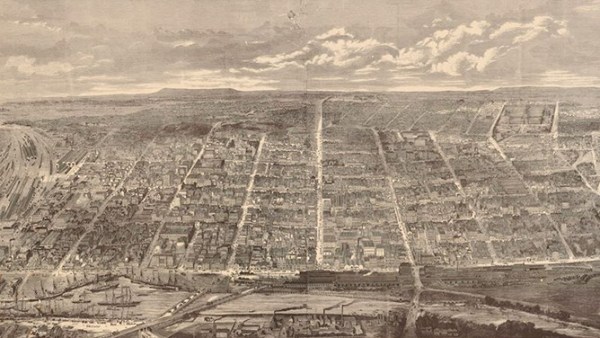

Melbourne's population reached 280,000 in 1880 and 445,000 in 1889. For a time, it was the second-largest city in the British Empire, after London. During this boom, Melbourne was said to be the richest city in the world. In terms of area, it was already one of the largest cities globally.

Instead of tall apartment blocks, Melbourne grew outwards in all directions. This led to the typical Australian "quarter acre block" in the suburbs, similar to the American Dream. Middle-class families lived in houses on large plots of land. Working-class people lived in comfortable cottages in the northern and western suburbs. Older areas like Fitzroy became crowded. Most new heavy industries were in the western suburbs. The very rich built huge mansions by the sea or in the scenic Yarra Valley.

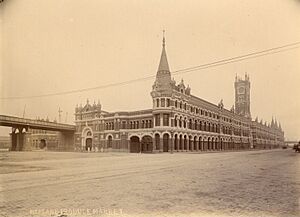

New suburbs were connected by train and tram networks, which were among the biggest and most modern in the world. Melbourne's pride was shown by the huge Royal Exhibition Building, built in 1880 for the Melbourne International Exhibition.

In the 1880s, the long boom ended in a frenzy of land speculation and rising prices, known as the Land Boom. Governments shared in the wealth and invested money into city infrastructure, especially railways. Huge fortunes were made from speculation, and Victorian business became known for corruption. English banks lent money easily to speculators, adding to the debt that built the boom.

The 1891 Economic Crash

In 1891, the boom ended suddenly with a spectacular crash. Many banks and businesses failed. Thousands of people lost their money, and tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs. It's thought that about 20 percent of people in Melbourne were unemployed throughout the 1890s.

Melbourne had 490,000 people in 1890. This number barely changed for the next 15 years due to the crash and the long economic slump. Immigration stopped, and many people moved to the goldfields of Western Australia and South Africa. The city's growth continued, but very slowly.

"Australia's Capital": 1901-1927

Melbourne was Australia's largest city long enough to become the seat of government for the new Commonwealth of Australia when the six colonies joined together in 1901. Parliament House in Spring Street was used by the Parliament of Australia. Victoria's Parliament moved temporarily to the Royal Exhibition Building.

The city's growth slowed, and by 1905, Sydney became Australia's largest city again. Economic growth slowly returned from 1900, and Melbourne's population reached 670,000 by 1914. But the big boom years did not return. Urban poverty became a problem, and slum areas in the inner suburbs grew.

Because of long delays in building a permanent capital at Canberra, Melbourne remained Australia's capital until 1927. That's when the parliament finally moved to Canberra. However, Melbourne remained an important centre for the Commonwealth Public Service, the Australian Defence Forces, and the High Court of Australia for some time after.

Between the World Wars

Melbourne's mood was also sad because of the huge losses in World War I. 112,000 Victorians joined the war, and 16,000 were killed. There were strong political disagreements during the war, especially about conscription. Another 4,000 Victorians died in the Spanish flu epidemic after the war.

There was a small return to good times in the 1920s. The population reached 1 million in 1930. But in 1929, the Wall Street Crash started the Great Depression, which lasted until a brief return to prosperity in the late 1930s. This was cut short by the start of World War II.

In 1934, Melbourne celebrated its 100th birthday and gained another important landmark, the Shrine of Remembrance on St Kilda Road. The population grew slowly again, reaching only 1.1 million in 1940.

World War II and After

During World War II, even though Canberra was the official capital, most of the military and government work was in Melbourne. The city's economy benefited from full employment during wartime. Many American service members came to Melbourne, including General Douglas MacArthur, who briefly had his headquarters in Collins Street.

Post-World War II Growth

After World War II, Melbourne entered a new time of increasing prosperity. This was helped by high prices for Victoria's wool, more government spending on transport and education, and a new wave of immigration. Unlike before the war, when most immigrants were from the British Isles, the postwar program brought many Europeans. At first, these were mostly refugees from eastern and central Europe. Many were Jews, making Melbourne's Jewish population the largest proportionally of any Australian city by 1970. They were followed by immigrants from Italy, Greece, and the Netherlands.

Later, in the 1960s, migrants came from Yugoslavia, Turkey, Hungary, and Lebanon. These new arrivals quickly changed the city's people and many parts of its life. This growth needed new spending on things like roads, schools, and hospitals, which had been neglected for decades. Henry Bolte, Premier from 1955 to 1972, was responsible for much of this fast development. Under Bolte, some old inner-city slums were knocked down, and the people living there were moved into tall government-owned apartment blocks.

Since the 1970s, Melbourne has changed even faster. The end of the White Australia Policy brought the first significant Asian migration to Melbourne since the gold rushes. Large numbers of people from Vietnam, Cambodia, and China arrived. For the first time, Melbourne gained a large Muslim population. The official policy of multiculturalism encouraged Melbourne's different ethnic and religious groups to keep and celebrate their cultures. At the same time, mainstream Christianity declined, leading to a more secular public life.

Government support for the arts led to a boom in festivals, theatre, music, and visual arts. Tourism became a major industry, bringing even more foreign visitors to Melbourne's streets. In 1956, Melbourne became the first city in the Southern Hemisphere to host the Olympic Games. Two new universities opened: Monash University in 1961 and La Trobe University in 1967. Others followed in the 1980s, keeping Melbourne a leader in higher education.

1980s and 1990s

The city continued to spread out, from Werribee in the south-west to Healesville in the north-east. It also included much of the Mornington Peninsula and Dandenong Ranges. A program of freeway construction was sped up in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the expansion of train and tram networks was neglected, apart from the opening of the City Loop in 1981. These changes led to a rapid increase in the number and use of private cars.

1989 Financial Crash

High interest rates and poor management led to a financial crash in 1989. Many banks and businesses failed, and property values dropped. This caused a deep recession. Melbourne's population growth slowed in the early 1990s as jobs decreased, and more people moved to other states like Queensland.

This recession contributed to the fall of Joan Kirner's Labor government. In 1992, a new Liberal government led by Jeff Kennett was elected. Kennett's team improved Victoria's finances by cutting public spending. They closed many schools, privatised the tramways and electricity, reduced government jobs, and changed local government. These changes had a high social cost, but they eventually brought back confidence in Melbourne's economy and led to growth again. Kennett was voted out of office in 1999. However, important landmarks his government started, like the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre and the new Melbourne Museum, remain. Many of his changes have also stayed.

Because it became harder to travel across the city, the central business centre declined. Satellite suburbs like Frankston, Dandenong, and Ringwood, and further out Melton, Sunbury, and Werribee, became centres for manufacturing, shops, and administration. As a result, factory jobs in the old working-class inner suburbs decreased. These areas quickly became more expensive and desirable in the 1990s and 2000s.

By the end of the 20th century, Melbourne had 3.8 million people.

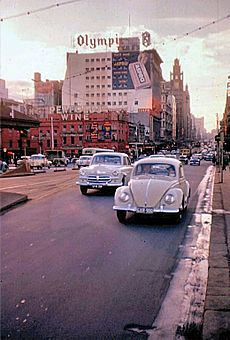

The 2000s

In the early 2000s, Melbourne began a new period of strong economic and population growth. This was under the Labor government of Steve Bracks, which increased public spending on health and education. As the city's suburbs continued to spread outwards, the Bracks government tried to limit new suburban growth to specific areas. They also encouraged more apartment living in the city's main transport hubs.

The city's Central Business District saw a big comeback in the 2000s. This was helped by a large increase in inner-city apartment living. New public spaces like Federation Square and the new Southern Cross railway station opened. Lord Mayor John So's City Council also ran a strong marketing campaign. Development continued in the Southbank and Docklands areas.

Since the late 2000s, population growth in Melbourne has sped up. The city has been expanding outwards with low-density suburban areas to fit more people. In 2009, the Victorian Government announced plans to extend the city's urban growth boundary. This could mean changing green areas and farmland into housing developments.

Since 1997, Melbourne has had significant population and job growth. There has been a lot of international investment in the city's industries and property market. Major inner-city areas like Southbank, Port Melbourne, Docklands, and South Wharf have been redeveloped. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Melbourne had the highest population increase and economic growth rate of any Australian capital city between 2001 and 2004.

Despite some challenges, Melbourne has seen continued growth in its cultural institutions. This includes art, music, literature, and performance. Many artists and supporters of the arts move to Melbourne because of its strong independent community support. In 2003, Melbourne was named a UNESCO City of Literature. The city hosts most of Australia's modern festivals, events, and institutions. New galleries, music venues, and museums are opening across the city.

From 2006, the city's growth extended into "green wedges" and beyond the city's urban growth boundary. Predictions that the city's population would reach 5 million pushed the state government to review the growth boundary in 2008. Melbourne handled the financial crisis of 2007-2010 better than any other Australian city. In 2009, more new jobs were created in Melbourne than in any other Australian capital. Melbourne's property market remained strong, leading to high property prices and rising rents.

The 2010s and 2020s

Starting in 2014, the State Government led by Daniel Andrews began several major projects. These were designed to reduce traffic, improve public transport, and encourage economic growth. Projects included the Metro Tunnel, the West Gate Tunnel, the North East Link, and the Suburban Rail Loop. The Level Crossing Removal Project removed 110 railway crossings, rebuilt stations, and changed suburbs across Melbourne. Other big projects included the Victorian School Building Authority and rebuilding Footscray Hospital. Plans for a Melbourne Airport rail link started in 2018 but were paused in 2023 due to high costs.

Melbourne was voted the world's most liveable city for seven years in a row, from 2011 to 2017.

New urban renewal areas opened in inner-city places like Fisherman's Bend and Arden. Suburban growth continued on the city's edges in suburbs like Wyndham Vale and Cranbourne. Middle suburbs like Box Hill became denser as more Melburnians started living in apartments. A construction boom saw 34 new skyscrapers built in the central business district between 2010 and 2020. In 2020, Melbourne was classified as an Alpha city, meaning it's a major global city.

The COVID-19 pandemic had its first Australian case in Melbourne on January 25, 2020. Out of all major Australian cities, Melbourne was the most affected by the pandemic. It spent a long time under lockdown rules, with six lockdowns lasting a total of 262 days. These public health policies led to anti-lockdown protests and civil unrest in 2021. While this caused a slight drop in Melbourne's population from 2020 to 2022, Melbourne is expected to be the fastest-growing capital city in Australia from 2023–24 onwards. It is projected to overtake Sydney as the nation's largest city around 2029–30, with over 5.9 million people, and exceed 6 million the following year.

See also

- Aboriginal sites of Victoria

- Culture of Melbourne

- History of Australia

- History of Victoria

- Timeline of Melbourne history

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |