History of Baden-Württemberg facts for kids

The history of Baden-Württemberg is about a special part of Germany. This area includes the old states of Baden, Württemberg, and Hohenzollern. It has been a key region in Swabia since the 800s.

Long ago, in the 1st century AD, the Romans took over Württemberg. They built a strong wall, called a limes, to protect their land. But in the early 200s, a group called the Alemanni pushed the Romans out. Later, the Franks, led by Clovis I, defeated the Alemanni in 496. This area then became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Baden started its history as a state in the 1100s. It was a small area ruled by a margrave. Over time, it grew bigger, especially during the time of Napoleon. It became a grand duchy. In 1871, Baden helped create the German Empire. After World War I, the monarchy ended, but Baden stayed a state until World War II.

Württemberg, sometimes spelled "Wirtemberg," grew into a political area in southwest Germany. Its main city was Stuttgart. The rulers, starting with Count Conrad around 1110, made Württemberg bigger. They survived many challenges, like religious wars and invasions from France. Württemberg became a kingdom from 1806 to 1918. Today, its land is part of the modern German state of Baden-Württemberg, which was formed in 1952. The state's coat of arms shows symbols from its important historical parts, especially Baden and Württemberg.

Contents

- Early People: Celts, Romans, and Alemanni

- The Duchy of Swabia

- Powerful Families: Hohenstaufen, Welf, and Zähringen

- Baden and Württemberg Before the Reformation

- The Reformation Period

- Peasants' War

- The Thirty Years' War

- Swabian Circle Until the French Revolution

- Southwest Germany Up to 1918

- German Southwest Up to World War II

- Southwest Germany After the War

- State of Baden-Württemberg from 1952 to Today

- See also

Early People: Celts, Romans, and Alemanni

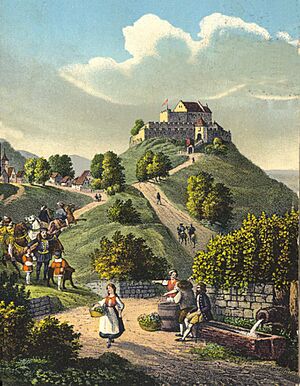

The name "Württemberg" has a mysterious past. Some people think it came from a person's name, while others believe it came from an old Celtic place. The name first belonged to a castle near Stuttgart. As the rulers of this castle gained more land, the name "Württemberg" spread across the whole area.

The first known people in Württemberg were the Celts. Then, the Romans arrived and took control. They built a strong wall called the limes to protect their land. But in the early 200s, the Alemanni pushed the Romans back beyond the Rhine and Danube rivers. However, the Alemanni were then defeated by the Franks, led by Clovis I, in a big battle in 496. For about 400 years, this area was part of the Frankish empire. It was ruled by counts until it became part of the German Duchy of Swabia in the 800s.

The Duchy of Swabia

The Duchy of Swabia was a large area, much like the land of the Alemanni. The name "Swabia" comes from the Suevi tribe, who were part of the Alemanni. From the 800s onwards, the area became known as "Swabia" instead of "Alemania." Swabia was one of the five main duchies of the medieval Kingdom of the East Franks. This meant its dukes were very powerful in Germany.

The Hohenstaufen family was the most famous to rule Swabia. They held the duchy from 1079 until 1268. For much of this time, the Hohenstaufen dukes were also Holy Roman Emperors. When Conradin, the last Hohenstaufen duke, died, the duchy broke apart.

Another important family was the House of Zähringen. They founded the city of Bern in 1191, which became a center of their power. However, when Duke Berthold V died in 1218 without children, the Zähringen duchy also fell apart. Bern then became a Free imperial city and later joined Switzerland in 1353.

After the Hohenstaufen family lost power, the Duchy of Swabia never truly came back together. The Habsburgs and the Württembergers tried to revive it, but they could not.

Powerful Families: Hohenstaufen, Welf, and Zähringen

Three noble families were very important in southwest Germany: the Hohenstaufen, the Welf, and the Zähringen. The Hohenstaufen family was the most successful. They were dukes of Swabia from 1079 and later became kings and emperors from 1138 to 1268. They had the most influence in Swabia. The Zähringer family controlled areas like Freiburg and Bern. These three families often competed, even though they were related. For example, the mother of the famous Hohenstaufen King Frederick Barbarossa (Red Beard) was from the Welf family.

During the Middle Ages, different counts ruled the land that is now Baden. The Zähringen family was very important among them. In 1112, Hermann, who inherited some German lands, started calling himself Margrave of Baden. This is when Baden's separate history began. His family grew their lands, which were then divided into different lines, like Baden-Baden and Baden-Hochberg. The Baden-Baden family was very good at making their lands bigger.

The Hohenstaufen family ruled the Duchy of Swabia until 1268. After that, a large part of their lands went to the counts of Württemberg. The first known Count of Württemberg was Ulrich I, Count of Württemberg, who ruled from 1241 to 1265. He gained a lot of land in the Neckar and Rems valleys. Under his sons, Ulrich II and Eberhard I, the family's power grew steadily.

Baden and Württemberg Before the Reformation

The Baden-Baden family was very successful in making their land bigger. After being divided several times, their lands were brought back together by Margrave Bernard I in 1391. Bernard was a famous soldier who continued to expand his territories. In 1503, the Baden-Sausenberg family line ended, and Christoph I united all of Baden. However, Baden was divided again from 1515 to 1771, and its different parts were not connected.

The lords of Württemberg were first mentioned in 1092. The new Wirtemberg Castle became the center of their rule. Over centuries, their land grew from the Neckar and Rems valleys in all directions.

Eberhard I, Count of Württemberg bravely stood against three Holy Roman Emperors. He doubled the size of his county and moved his home from Württemberg Castle to the "Old Castle" in Stuttgart.

His successors also added to Württemberg's land. In 1381, they bought the Duchy of Teck. In 1397, they gained Montbéliard through marriage. The family divided their lands sometimes, but in 1482, the Treaty of Münsingen reunited the territory. It said the land could not be divided again and would be ruled by Count Eberhard V, known as im Bart (The Bearded). This agreement was approved by Emperor Maximilian I in 1495.

Unusually for Germany, Württemberg had a two-house parliament called the Landtag from 1457. This parliament had to approve new taxes.

In 1477, Eberhard V founded the University of Tübingen. When Eberhard died in 1496, his cousin, Duke Eberhard II, ruled for only two years before being removed from power.

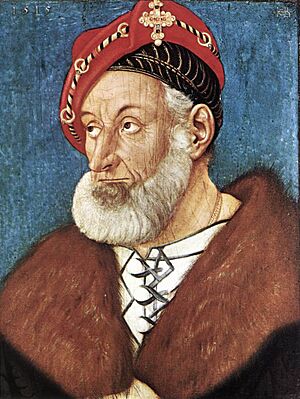

Eberhard V was one of Württemberg's most active rulers. In 1495, his county became a duchy. He was now Duke Eberhard I of Württemberg. After being divided from 1442 to 1482, Württemberg stayed a united country.

The Reformation Period

Martin Luther's ideas in 1517 changed Germany forever. In 1503, the Baden-Sausenberg family line ended, and Christoph united all of Baden. Before he died in 1527, he divided it among his three sons. Differences in religion made the family rivals. During the Reformation, some rulers of Baden stayed Catholic, while others became Protestants. In 1535, Christoph's sons Bernard and Ernest divided their lands again, creating the lines of Baden-Baden and Baden-Pforzheim (later Baden-Durlach). More divisions followed, and the rivalry between the two main family branches led to fighting.

The long rule (1498–1550) of Duke Ulrich was very eventful. He became duke as a child. Duke Ulrich had been living in his County of Mömpelgard since 1519. He was forced out of his duchy because of his own mistakes and actions against other lands. In Basel, Duke Ulrich learned about the Reformation.

With help from Philip of Hesse and other Protestant princes, Ulrich won a battle against Ferdinand's troops in May 1534. By the treaty of Cadan, he became duke again, but his duchy was now under Austrian control. He then brought in new religious ideas, supported Protestant churches and schools, and founded the Tübinger Stift seminary in 1536. Ulrich's connection with the Schmalkaldic League led to him being forced out again. But in 1547, Charles V put him back in power, though with strict rules.

During the 1500s, Württemberg had between 300,000 and 400,000 people. Ulrich's son, Christoph (1515–1568), finished changing his people to the reformed faith. He set up a church system called the Grosse Kirchenordnung, which lasted for centuries. During his rule, a group was formed to manage money. Its members, who were from the upper classes, gained a lot of power.

Christoph's son Louis died in 1593 without children. His relative, Frederick I (1557–1608), became duke. This active prince ignored the limits on his power. In 1599, he paid a lot of money to Emperor Rudolph II to free the duchy from Austrian control. Austria still held large areas around the duchy, known as "Further Austria". So, Württemberg became a direct part of the empire again, making it independent. The Margraviate of Baden-Baden also became Lutheran that year, but only for a short time. The Counter-Reformation also began, strongly supported by the Emperor.

Peasants' War

At the start of the 1500s, farmers in southwest Germany lived simple lives. But higher taxes and bad harvests made things very hard. Rebellions broke out in different areas, marked by the symbol of the farmer's shoe (Bundschuh). Duke Ulrich's demands for money for his lavish lifestyle caused an uprising called the arme Konrad (Poor Conrad). This was similar to the rebellion led by Wat Tyler in England. The authorities quickly brought order back. In 1514, by the Treaty of Tübingen, the people agreed to pay the duke's debts in exchange for political rights. These rights became the basis for the country's freedoms.

A few years later, Ulrich had a conflict with the Swabian League. Their forces, helped by Duke William IV of Bavaria, invaded Württemberg. They forced the duke out and sold his duchy to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, for a large sum of money.

Charles gave Württemberg to his brother, Emperor Ferdinand I. But people were unhappy with Austrian rule. The German Peasants' War and the Reformation gave Ulrich a chance to get his duchy back. Marx Sittich of Hohenems defeated the last peasant uprising on November 4, 1525. Emperor Karl V and even Pope Clement VII thanked the Swabian Union for their actions during the Peasants' War.

The Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was the longest war in German history. It became a global conflict because major powers got involved. The main reason for the war was the conflict between different Christian groups after the Reformation. In southwest Germany, Catholic princes (like the Emperor and Bavaria) were in the League, while Protestant princes (like the Electorate Palatine, Baden-Durlach, and Württemberg) were in the Union.

Unlike his father, Duke Johann Frederick (1582–1628) could not become an absolute ruler. He had to accept limits on his power. During his rule, Württemberg suffered greatly from the Thirty Years' War, even though the duke did not fight in it himself. His son, Eberhard III (1628–1674), joined the war as an ally of France and Sweden in 1633. But after the Battle of Nordlingen in 1634, Imperial troops took over the duchy, and the duke had to leave for some years. The Peace of Westphalia brought him back, but to a country that had lost many people and was very poor. He spent his remaining years trying to fix the damage from the long war. Württemberg was a central battleground. Its population dropped by 57% between 1634 and 1655, mostly due to deaths, disease, fewer births, and many scared farmers moving away.

From 1584 to 1622, Baden-Baden was ruled by a prince from Baden-Durlach. The family was also divided during the Thirty Years' War. Baden suffered a lot, and both branches of the family were forced into exile at different times. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 brought things back to how they were. The family rivalry slowly ended. For some parts of the southwest, a 150-year period of peace began. However, in other areas, especially the Electorate Palatine, the wars started by French King Louis XIV from 1674 to 1714 caused more terrible destruction. France expanded its territory to the Rhine border. Switzerland also separated from the Holy Roman Empire.

Swabian Circle Until the French Revolution

The Duchy of Württemberg survived mainly because it was larger than its neighbors. However, it often faced challenges during the Reformation from the Catholic Holy Roman Empire. It also suffered from repeated French invasions in the 1600s and 1700s. Württemberg was often in the path of French and Austrian armies fighting each other.

During the wars of Louis XIV of France, the margravate of Baden was destroyed by French troops. Towns like Pforzheim, Durlach, and Baden were ruined. Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden (died 1707) was a famous soldier who fought against France.

Charles Frederick of Baden-Durlach worked his whole life to unite his country. He started ruling in 1738 and became an adult in 1746. He was the most important ruler of Baden. He cared about farming and trade, and he wanted to improve education and justice. He was a wise and fair ruler during the Age of Enlightenment.

In 1771, Augustus George of Baden-Baden died without sons. His lands went to Charles Frederick, who finally became the ruler of all Baden. Even though Baden was united under one ruler, its customs, taxes, laws, and government were not united. Baden was not a single, connected territory. Instead, it had many separate areas on both sides of the upper Rhine. Charles Frederick got his chance to expand his territory during the Napoleonic wars.

During the rule of Eberhard Louis (1676–1733), Württemberg faced another destructive enemy: Louis XIV of France. In 1688, 1703, and 1707, the French entered the duchy and caused great suffering to the people. The country had few people, so it welcomed Waldenses (a religious group) who helped it become prosperous again. But the duke spent too much money on his mistress, Christiana Wilhelmina von Grävenitz, which hurt the country's finances.

In 1704, Eberhard Ludwig began building Ludwigsburg Palace north of Stuttgart, trying to copy the grand Versailles.

Charles Alexander, who became duke in 1733, had become a Roman Catholic while serving in the Austrian army. His favorite advisor was a Jewish man named Joseph Süß Oppenheimer. People suspected that the duke and his advisor wanted to get rid of the local parliament (the diet) and bring in Roman Catholicism. However, Charles Alexander died suddenly in March 1737, ending these plans. The regent, Duke Carl Rudolf, had Oppenheimer executed.

Charles Eugene (1728–1793) became an adult in 1744. He seemed talented but was wild and spent too much money. He built the "New Castle" in Stuttgart and other places. He sided against Prussia during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), which his Protestant people did not like. His entire rule was marked by disagreements between him and his people. The duke's unfair ways of raising money caused great unhappiness. The emperor and even foreign powers got involved. In 1770, a formal agreement helped fix some of the people's complaints. Charles Eugene did not always keep his promises, but later in his old age, he made a few more concessions.

Charles Eugene had no legal children. His brother, Louis Eugene (died 1795), who also had no children, succeeded him. Then another brother, Frederick Eugene (died 1797), became duke. This prince had served in the army of Frederick the Great and raised his children as Protestants who spoke French. All later Württemberg royal family members came from him. So, when his son Frederick II became duke in 1797, Protestantism returned to the ducal family.

Southwest Germany Up to 1918

After the French Revolution in 1789, Napoleon, the French emperor, became the ruler of Europe. His actions changed the political map of southwest Germany. When the French Revolution threatened Europe in 1792, Baden joined forces against France. Its countryside was ruined by battles. In 1796, the margrave had to pay money and give up his lands on the left bank of the Rhine to France. But soon, his luck changed.

In 1803, thanks to Emperor Alexander I of Russia, the margrave received new lands and the title of a prince-elector. In 1805, he switched sides and fought for Napoleon. As a result, by the Peace of Pressburg, he gained more territories from the Habsburgs. In 1806, the Baden margrave joined the Confederation of the Rhine, declared himself a sovereign prince, became a grand duke, and received even more land.

On January 1, 1806, Duke Frederick II became King Frederick I. He ended the old constitution and united the old and new parts of Württemberg. He also put church lands under state control. In 1806, he joined the Confederation of the Rhine and gained more land with 160,000 people. Later, in October 1809, he gained about 110,000 more people.

In return for these gains, Frederick joined Napoleon in his wars against Prussia, Austria, and Russia. About 16,000 of his soldiers marched with the French to Moscow, but only a few hundred returned. After the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, King Frederick left Napoleon's side. By a treaty with Metternich in November 1813, he kept his royal title and his new lands. He then sent his troops to fight with the allies against France.

In 1815, the king joined the German Confederation. The Congress of Vienna did not change the size of his lands. That same year, he suggested a new constitution, but his people's representatives rejected it. Amidst this disagreement, Frederick died on October 30, 1816.

The new king, William I (ruled 1816–1864), immediately worked on the constitution. After much discussion, he granted a new constitution in September 1819. This constitution, with some changes, lasted until 1918. A period of peace began. The kingdom focused on improving education, farming, trade, and manufacturing. King William I helped fix the country's finances. But people still wanted more political freedom. After 1830, there was some unrest, but it soon faded. Württemberg joining the German Zollverein (customs union) and building railways helped trade grow.

The revolutionary movement of 1848 affected Württemberg, but there was no violence. King William had to fire his ministers and bring in more liberal leaders who supported a united Germany. King William announced a democratic constitution. But as soon as the movement weakened, he dismissed the liberal ministers. In October 1849, his old ministers returned to power. In Baden, however, there was a serious uprising that had to be stopped by force.

By changing voting rights, the king and his ministers managed to get a parliament that gave up all the freedoms gained since 1848. This brought back the 1819 constitution, and power returned to the government officials. A deal with the Papacy was almost the last act of William's long rule. But the parliament rejected the agreement, preferring to manage church and state relations their own way.

In July 1864, Charles (1823–1891, ruled 1864–91) became king after his father William I died. He immediately faced big problems. In the fight between Austria and Prussia for power in Germany, William I had always supported Austria. The new king and his advisors continued this policy.

In 1866, Württemberg fought for Austria in the Austro-Prussian War. But three weeks after the Battle of Königgrätz on July 3, 1866, Württemberg's troops were badly defeated. The country was at Prussia's mercy. The Prussians took over northern Württemberg and made a peace deal in August 1866. Württemberg had to pay a large sum of money. But it also secretly agreed to an alliance with Prussia.

The end of the fight against Prussia allowed people in Württemberg to push for more democracy again. But no changes happened before the big war between France and Prussia broke out in 1870. Even though Württemberg had been against Prussia, the kingdom joined the national excitement across Germany. Its troops fought well in the Battle of Wörth and other parts of the war.

In 1871, Württemberg became part of the new German Empire. But it kept control of its own post office, telegraphs, and railways. It also had special rights regarding taxes and the army. For the next 10 years, Württemberg strongly supported the new empire. Many important changes, especially in money matters, happened. But a plan to combine the railway system with the rest of Germany failed. After tax cuts in 1889, changing the constitution became the main issue. King Charles and his ministers wanted to make the conservative side stronger in parliament. But laws from 1874, 1876, and 1879 only made small changes. On October 6, 1891, King Charles died suddenly. His nephew, William II (1848–1921, ruled 1891–1918), became king and continued his uncle's policies.

Discussions about changing the constitution continued. In the 1895 election, a strong party of democrats was elected. King William had no sons, and his only Protestant relative, Duke Nicholas (1833–1903), also had no sons. This meant the throne would eventually go to a Catholic branch of the family. This caused some issues about the relationship between church and state. The heir to the throne in 1910 was the Catholic Duke Albert (born 1865).

Between 1900 and 1910, Württemberg's politics focused on solving constitutional and education issues. The constitution was changed in 1906, and the education problem was resolved in 1909. In 1904, the railway system became part of Germany's main railway network.

In 1905, the population was 2,302,179. About 69% were Protestant, 30% Catholic, and 0.5% Jewish. Protestants were mostly in the Neckar district, and Catholics in the Danube district. In 1910, about 506,061 people worked in farming, 432,114 in factories, and 100,109 in trade and business.

During the confusion at the end of World War I, Frederick gave up his throne on November 22, 1918. A republic had already been declared on November 14. Württemberg became a state (Land) in the new Weimar Republic. Baden called itself a "democratic republic," and Württemberg a "free popular state." Instead of kings, state presidents were in charge. They were chosen by the state parliaments.

German Southwest Up to World War II

Plans to combine Württemberg and Baden between 1918 and 1919 mostly failed. After the exciting revolution of 1918–1919, election results in Württemberg from 1919 to 1932 showed fewer votes for left-wing parties.

In the Reichstag election on March 5, 1933, about 86% of people in Württemberg voted. The Nazis won 42% of the vote, up from 26% in November 1932. On March 8, 1933, Adolf Hitler used his power to appoint a local SA leader, Dietrich von Jagow, as the police chief for Württemberg. Jagow began a very harsh rule, using the SA and police against Jews, Social Democrats, and Communists. Jagow opened a concentration camp at Heuberg in March 1933, holding 1,902 people. By December 1933, the number rose to 15,000 before it was closed. The Nazis in Württemberg had many internal conflicts. The local Nazi party was very disorganized as its leaders fought for control. After the Nazi party took power in 1933, the state borders stayed the same. Baden, Württemberg, and Hohenzollern continued to exist, but with much less self-rule under the main German government. From 1934, the Gau of Württemberg-Hohenzollern included the Province of Hohenzollern.

Even though there were few Jewish people in Württemberg, Jewish traders were important for connecting rural markets to cities. Most farmers in Württemberg did not like the Nazi government's efforts to stop Jewish traders, but only because it hurt their own business. Most Jews in cities had adopted German culture, while most Jews in rural areas were more traditional and kept some distance from their non-Jewish neighbors. By 1939, most Jews who had lived in Württemberg had moved abroad. Only a quarter of the Jews who were there in 1933 remained by 1939. Many went to the United States, and some also went to the United Kingdom, France, modern Israel, and Argentina. In the 1930s, it was hard for women to find jobs. Because of this, Jewish women were more likely to stay in Württemberg, fearing they would not find work abroad.

Starting in January 1939, the Nazi government began a program to kill Germans with physical or learning disabilities. This program aimed to remove "useless eaters" from society. In October 1939, this program reached Württemberg. Schloss Grafeneck, a home for people with disabilities near Stuttgart, was turned into a killing center with gas chambers and a crematorium.

By December 1940, Schloss Grafeneck was closed because most people classified as "useless eaters" in Württemberg had been killed.

During World War II, Württemberg's population changed a lot. Hundreds of thousands of men were called to serve in the army. Hundreds of thousands of Poles and French people were brought to Württemberg to work in factories and on farms, almost like slaves. By October 1940, 17,500 Poles worked on Württemberg's farms. This number grew as the war continued and more farmers were drafted into the army. Rules for Poles in Württemberg included a curfew, needing special permits for public transport, and being banned from restaurants, telephones, radios, bicycles, and cameras. They were also not allowed to sit on public transport. Although rules said Poles should attend separate church services, some Catholic priests ignored this and allowed Poles to attend Mass with Germans, which the Nazi government disliked.

Starting in the summer of 1941, many Soviet prisoners of war were also forced into labor.

On the night of May 5, 1942, Stuttgart was bombed for the fourth time. This raid killed 13 people, the first deaths from an air raid in Stuttgart since 1940. Later in May–June 1942, British bombers tried to destroy the Bosch factory in Stuttgart, which made generators, but they were not successful. An attempt to destroy the SKF factory, which made ball-bearings, in September 1943 also failed, with heavy losses. Daimler-Benz spread its production around Stuttgart, which helped protect it, even though it slowed down making aircraft engines and parts for military vehicles. From April 1943 onwards, bombers regularly attacked cities and towns in Württemberg at night, causing much damage. On the night of April 27, 1943, Friedrichshafen was heavily bombed to destroy three factories making tank engines. On September 6, 1943, Stuttgart was bombed during the day for the first time by the United States Army Air Force, killing 107 people. On April 27–28, 1944, Friedrichshafen was heavily bombed again, destroying 40% of its buildings.

The heaviest bombings happened between July 25 and 30, 1944. Bombers attacked Stuttgart nightly, destroying all of downtown Stuttgart, killing about 1,000 people, and leaving 100,000 homeless. On July 27, 1944, Friedrichshafen was heavily bombed again to destroy a factory making jet engines. Stuttgart was hit hard again in September–October 1944 by bombings aimed at the railway system, which also badly damaged the water and sewage systems. The worst bombings were on October 19–20, 1944, killing 338 people and wounding 872. By this time, the mayor, Dr. Karl Strölin, had asked all non-essential people to leave Stuttgart. By late 1944, Daimler-Benz had to move its Stuttgart factories underground to keep them working. In September 1944, Heilbronn was bombed so often that local Nazi officials asked permission to move non-essential people out, but this was denied. On December 4, 1944, Heilbronn was badly damaged in an air raid that killed about 6,000 people and turned the entire downtown into ruins. Ulm was badly damaged on December 17, 1944. The only city in Württemberg that avoided major damage was Tübingen, a university city with no major industries to bomb.

In October 1944, American and French forces entered Baden, and soon after, Württemberg. By April 30, 1945, all of Baden, Württemberg, and Hohenzollern were fully taken over by American and French forces.

Southwest Germany After the War

After World War II, the states of Baden and Württemberg were divided. The northern parts went to the American occupation zone, and the southern parts, along with Hohenzollern, went to the French zone. The border between these zones followed district lines. It was drawn so that the highway from Karlsruhe to Munich (today the Bundesautobahn 8) was entirely in the American zone. In the American zone, the state of Württemberg-Baden was created. In the French zone, the southern part of old Baden became the new state of Baden, while the southern part of Württemberg and Hohenzollern were combined into Württemberg-Hohenzollern.

A German law allowed states to be changed by a public vote. However, this could not happen because the Allied forces did not allow it. Instead, a special rule said that the three states in the southwest had to combine through an agreement. If they could not agree, a federal law would decide their future. This rule came from a meeting in 1948 where they agreed to create a "Southwest State." The other option, favored in South Baden, was to bring back Baden and Württemberg (including Hohenzollern) with their old borders.

The agreement failed because the states could not agree on how to vote. So, a federal law on May 4, 1951, decided the area would be split into four voting districts: North Württemberg, South Württemberg, North Baden, and South Baden. It was clear that both Württemberg districts and North Baden would support the merger. So, the voting system favored those who wanted the new Southwest State. The state of Baden took the law to the German Constitutional Court, saying it was against the constitution, but they lost.

The public vote happened on December 9, 1951. In both parts of Württemberg, 93% voted for the merger. In North Baden, 57% voted for it. But in South Baden, only 38% were in favor. Because three out of four voting districts voted for the new Southwest State, the merger was approved. If Baden as a whole had been one voting district, the merger would have failed.

State of Baden-Württemberg from 1952 to Today

The people who would write the new state's constitution were chosen on March 9, 1952. On April 25, the Prime Minister was elected. This is how the new state of Baden-Württemberg was created. After the new state's constitution became law, these members formed the state parliament until the first election in 1956. The name Baden-Württemberg was only meant to be temporary. But it became the official name because no one could agree on another one.

In May 1954, the Baden-Württemberg Landtag (parliament) chose a new coat of arms. It has three black lions on a gold shield, with a deer and a griffin on the sides. This coat of arms once belonged to the Staufen family, who were emperors and dukes of Swabia. The golden deer represents Württemberg, and the griffin represents Baden. Also, some former Württemberg areas were moved into Baden's government districts. The last parts of Hohenzollern disappeared. New regional groups were formed to help with planning between counties and districts.

Those who were against the merger did not give up. After Germany gained full independence, they asked for another public vote to bring Baden back to its old borders. They argued that the state had been changed after the war without a proper public vote. The government refused, saying a vote had already happened. The opponents sued in the German Constitutional Court and won in 1956. The court decided that the 1951 vote was not fair because the more populated state of Württemberg had an advantage over less populated Baden. But the court did not set a date for the new vote, so the government did nothing. The opponents sued again in 1969. This led to a decision that the vote had to happen before June 30, 1970. On June 7, most people voted against bringing back the old state of Baden.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Baden-Wurtemberg para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Baden-Wurtemberg para niños

- Timeline of Stuttgart

- History of Südwestrundfunk; the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) is the public broadcasting company for Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate.

- History of Franconia

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |