History of Málaga facts for kids

The history of Málaga is a long and exciting story, stretching back about 2,800 years! This makes Málaga one of the oldest cities in the world. It's located in southern Spain, right on the western shore of the Mediterranean Sea.

The first people to live here might have been the Bastetani, an ancient Iberian tribe. Later, around 770 BC, the Phoenicians arrived and started a colony called Malaka. After the 6th century BC, the powerful city of Carthage (in modern-day Tunisia) took control.

Around 218 BC, Malaca became part of the Roman Republic. By the end of the 1st century, under Emperor Domitian, it was a special city linked to the Roman Empire. It even had its own laws, which gave free people the rights of Roman citizenship.

When the Roman Empire weakened in the 5th century, Germanic peoples invaded. The Byzantine Empire then took over Málaga and other coastal cities, creating a new province called Spania in 552. This Byzantine rule lasted until 624.

After the Muslim conquest of Spain (711–718), the city was known as Mālaqah. It was surrounded by walls, and merchants from Genoa and Jewish communities settled in their own areas. In 1026, it became the capital of the Taifa of Málaga, an independent Muslim kingdom. This kingdom existed at different times until 1239, when it was conquered by the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada.

The Isabella and Ferdinand besieged Mālaqa in 1487. This was one of the longest sieges during the Reconquista. The Muslim people who resisted were punished severely. Under Castilian rule, new churches and convents were built outside the city walls. This helped new Christian neighborhoods grow. In the 16th century, Málaga faced a slow decline due to diseases, bad harvests, floods, and earthquakes.

In the 18th century, the city started to recover. During the 19th century, Málaga was a very rebellious city. It played a big part in the success of Spanish liberalism. Even though it was a time of crisis, Málaga was a leader in the Industrial Revolution in Spain. Powerful families from Málaga became very important, even in national politics. In 1873, during the First Spanish Republic, Málaga declared itself an independent "Canton" for a short time.

A new decline began in 1880. The economic crisis of 1893 forced factories to close. The sugar industry collapsed, and a disease called phylloxera destroyed the vineyards. The early 20th century was a time of economic changes. Industries closed, and trade went up and down. Economic problems and social unrest helped republican and labor movements grow stronger.

In 1933, during the Second Spanish Republic, Málaga elected the first member of the Communist Party of Spain to Parliament. In February 1937, the nationalist army, with help from Italian soldiers, attacked the city. They took control on February 7. Many people faced harsh punishments, and thousands lost their lives during this time.

During the military dictatorship, Málaga saw a huge growth in tourism. The Costa del Sol became very popular, leading to an economic boom in the 1960s. After the dictatorship ended, the first mayor from the Spanish Socialist Workers Party was elected. Later, the conservative Popular Party won and has governed since.

Contents

Ancient Málaga: From Caves to Cities

The area around Málaga has been home to people for a very long time. We know this from cave paintings in places like the Cueva de la Pileta. There are also tools and skeletons found in the Nerja Caves. Some paintings of seals in the Nerja Caves might be 42,000 years old. These could be the first known works of art by Neanderthals!

Phoenician Malake: A Trading Hub

The first settlers from other lands were the seafaring Phoenicians from Tyre. They arrived around 770 BC. They built their first settlement on a small island in the River Guadalhorce estuary at Cerro del Villar. The coastline has changed a lot since then, so this spot is now inland.

The Phoenicians chose this island because it was a great place for trade. It also had an excellent natural harbor. Ships going towards the Strait of Gibraltar could find protection there. From Cerro del Villar, the Phoenicians traded with local villages. Slowly, their main trading center moved to the mainland. This is where the new colony of Malake was founded. It became a busy commercial hub from the 8th century BC.

Malake's economy included making sea salt and possibly purple dye. The Phoenicians found special sea snails off the coast that produced this famous dye. The city even had its own mint and made coins. The Phoenician period lasted from about 770 to 550 BC.

The Phoenicians' power in the Mediterranean began to fade after Tyre was destroyed in 572 BC. Their place was taken by the Carthaginians. Carthage was a Phoenician trading post founded in 814 BC. Many Phoenicians likely moved to Carthage after the Persian conquest. Carthage soon became a strong trading power in the Mediterranean.

Greek Mainake: A Rival Settlement

The Phoenicians had many settlements along the coast east of Gibraltar. The Greeks also wanted to trade in Iberia. They set up their own trading colonies further north. The Tartessians, a local group, may have encouraged the Greeks. They wanted to end the Phoenician trade monopoly. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that around 630 BC, the Phocaeans made friends with King Arganthonios of Tartessos. He even gave them money to build walls around their city. Later, the Greeks founded Mainake on the Málaga coast.

Carthaginian Control: A New Power

When the Phoenician city-states in the eastern Mediterranean became part of the Persian empire, Carthage took over their trade. Malake became a colony of Carthage in 573 BC. The city's focus on trade, which started under the Phoenicians, continued. People also kept worshiping Phoenician gods like Melqart and Tanit.

The second half of the sixth century BC was a time of change for Málaga. It moved from Phoenician to Carthaginian rule. Carthage became the main Phoenician military power in the western Mediterranean. They closed the Strait of Gibraltar to Greek ships by 480 BC. This stopped the Greek expansion in Spain.

Carthage then destroyed Tartessos and pushed the Greeks out of southern Iberia. They protected their trade monopoly fiercely. In the 3rd century BC, Carthage made Iberia a new base for its empire. They expanded along the northern Mediterranean coast and built a new capital at Cartagena.

The Romans conquered Málaga and other Carthaginian areas after the Punic Wars in 218 BC.

Roman Malaca: A Time of Growth

The Romans took control of Málaga peacefully. They united the people of the coast and inland areas. Roman settlers used local resources and brought Latin as the main language. They also introduced new customs that slowly changed the local culture. Malaca became part of the Roman Republic. It was a stop on the Via Herculea, a major road. This road connected the city with other important places and Mediterranean ports. This helped Malaca's economy and culture grow.

When the Roman Empire began, Malaca was part of the province of Baetica. This province was rich and fully Romanized. Emperor Vespasian gave its people the rights of Roman citizenship. This made the wealthy and middle classes loyal to Rome.

The city had an unusual layout, like other Phoenician cities. The Romans built important public works. The Flavian dynasty improved the port. Emperor Augustus built the Roman theater. Later, Emperor Titus gave Malaca its special status as a municipality.

Malaca became a very developed city during this time. It was a federated city of the empire. It was governed by its own laws, called the Lex Flavia Malacitana. Many educated people lived there and supported the arts. Large Roman baths were built, and many sculptures from this period are now in the Museo de Málaga.

The Roman theater, built in the 1st century BC, was found by accident in 1951. It is well preserved but not fully dug up. It seems the theater was abandoned in the 3rd century. Its materials were later used by the Arabs to build the Alcazaba.

The economy relied on farming inland, fishing, and local crafts. Málaga exported wine, olive oil, and garum malacitano. This was a fermented fish sauce famous throughout the empire. Different groups in Malaca followed their own religions. By 325 AD, Christianity was strong in Málaga. Spain's languages, religion, and laws today come from the Roman period. Roman rule left a deep and lasting mark on Málaga's culture.

Germanic Invasions and Visigothic Rule

In the 5th century, Germanic peoples like the Visigoths crossed into Spain. The Visigoths became the strongest power. Around 511, they moved to the Málaga coast. Spain remained quite Romanized under their rule. The Visigoths adopted Roman culture and language. They also kept many old Roman institutions.

Under Visigothic rule, Málaga became an important religious center. The first known bishop was Patricius, around 290 AD.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, Málaga was affected by more Germanic tribes. The province lost much of its wealth and buildings from Roman rule. But it still managed to be somewhat prosperous. Some important towns were destroyed and not rebuilt.

Byzantine Malaca: A Brief Return

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I wanted to get back the lands of the Western Roman Empire. His general, Belisarius, succeeded in taking North Africa, southern Iberia, and most of Italy. Málaga and its area were conquered in 552. Málaga then became a very important city in the Byzantine province of Spania.

The city was conquered and attacked again by the Visigoths in 615. In 624, the Byzantines finally left their last settlements in Spain.

The Visigothic king Sisebut damaged much of the city. Although it remained a religious center, its population greatly decreased. Its rich economy was ruined. When the first Islamic invaders arrived, they had to set up their capital inland, at Archidona.

Eight Centuries of Muslim Rule

The Arabs began conquering Spain around 711. The Visigothic kingdom collapsed, and Muslim armies moved north. By 714, most of Spain was under Muslim control. Málaga was settled by Arabs and Berbers. Many local people fled to the mountains. The Muslims called the city Mālaqa. It became part of the region of al-Andalus.

After the fall of the Umayyad dynasty, Mālaqa became the capital of its own kingdom (taifa). This kingdom was linked to Granada.

Local people who had converted to Islam, called Muladi, often rebelled against the Arab and Berber immigrants. These immigrants had taken large estates. The most famous revolt was led by Umar ibn Hafsun in the Málaga region. He ruled for almost 40 years from his castle, Bobastro. He gathered unhappy Muladi and Christians to his side. He even became a Christian himself in 889. But this made him lose support from many of his Muladi followers.

When Hafs, Umar ibn Hafsun's son, surrendered in 928, Abd-al-Rahman III brought Islamic civil organization to Mālaqa. This led to new population patterns. It encouraged city growth and many farms in rural areas. Farmers used advanced irrigation. Crafts and trade thrived in the cities. This brought prosperity and peace to the province.

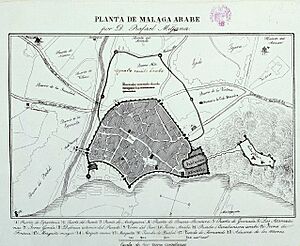

Mālaqa city itself grew and prospered. It was surrounded by walls with five large gates. The Alcazaba, a Moorish fortress, was built in the mid-11th century. It was on Mount Gibralfaro, a hill overlooking the port. The fortress had two walled areas that followed the steep land. It was fortified with three walls towards the sea and two facing the town. New neighborhoods grew as the city expanded. These included walled areas with adarves, which were streets leading to private homes.

The banks of the Wad-al-Medina (Guadalmedina river) had many orchards. A route connected the harbor and the fortress. Genoese and Jewish merchants settled in their own areas near the city walls. The Jewish quarter produced a famous son of Mālaqa: the philosopher and poet Solomon Ibn Gabirol. He was the first to call his hometown "Paradise City."

Besides the amazing Alcazaba, other parts of Moorish Mālaqa remain. These include the marble gate of the Nasrid shipyards (atarazanas) and part of the Jewish quarter. A section of the large cemetery of Yabal Faruh has also been found.

Taifa of Mālaqa: An Independent Kingdom

In 1026, Mālaqa became the capital of the Taifa of Málaga. This was an independent Muslim kingdom. It was ruled by different families at different times. It existed from 1026 to 1057, then 1073 to 1090, 1145 to 1153, and finally 1229 to 1239. After that, it was conquered by the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada.

Parts of the city's layout from this time are still in the historical center. This includes the Alcazaba and the castle of Gibralfaro. La Coracha was a walled passage that connected the fortress and the Alcazaba. Mālaqa had two suburbs outside its walls. It had a busy trade with the Maghreb (North Africa). The city had an important pottery industry. Its ornamental vases, called Málagan lusterware, were famous throughout the Mediterranean.

Nasrid Mālaqa: Trade and Shipbuilding

After the last king of the Mālaqa Taifa died in 1238, the city was captured by Muhammad I of Granada in 1239. It became part of the Moorish kingdom of Granada. Mālaqa remained under the rule of the Nasrid dynasty until the Christian Reconquista.

During the Nasrid rule, Mālaqa became a center for shipbuilding and international trade. In 1279, Muhammad II signed a trade agreement with Genoa. Genoese traders gained a special position in the port. By the mid-14th century, Mālaqa was the main port for the Nasrid kingdom.

The Genoese set up a network of trade centers around the Mediterranean. They connected Iberian trade with North Africa. Many of these communities formed groups called consulados to help merchants. A ship's logbook from 1445 shows Mālaqa was a key part of this trade network. It became an important business hub.

Fine ceramics made in Mālaqa were often given as diplomatic gifts. Workshops for these ceramics were in the Fontanalla suburb.

The Mālaqa shipyards, called the Atarazanas, were built during the reign of Mohammed V (1354–1391). This was to strengthen his power. The main building was a large naval workshop. It was known for its seven huge horseshoe arches. The coast was further inland then, and the Atarazanas was right by the sea. Water flowed in, creating a basin big enough for 20 galleys.

About 15,000 people lived in Mālaqa at this time. Most were Muslims who followed religious laws strictly. There was a good number of Jews. The number of Christians was small, mostly captives forced to work. The small group of foreign traders was mostly Genoese. The city's governor was usually a Moorish prince. He lived in the Alcazaba. The city's defenses were very strong, with massive walls, towers, and the Gibralfaro fortress.

The mountainous land around Mālaqa was not great for farming. But Muslim farmers created a good irrigation system. They grew crops on the slopes, with spring wheat as their main food. An unusual thing was growing grapevines and fig trees together. Livestock farming was less important. Olive production was low, and olive oil was imported. Other fruits and nuts like figs, hazelnuts, walnuts, chestnuts, and almonds were plentiful. Mulberry trees, brought by the Arabs, were used for juice.

Trade in hides, skins, and leatherworking was a big industry. Metalworking, especially knives and scissors, was also important. Gold-inlaid ceramics and porcelain were made. Silk textiles were still important, linked to the Moorish population. Light ships for patrolling the coast were built in the Atarazanas.

In 1348, while the Black Plague was in Europe, the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro castle were completed. The city had several gates through its walls. Some, like the Puerta Oscura (Dark Gate) and Puerta del Mar (Sea Gate), still stand. The Alcazaba was the Moorish fortress on Mount Gibralfaro. It was connected to the castle by a passage called La Coracha. Built in the 11th century, the Alcazaba had defenses and palaces with gardens. It had 110 large towers and many smaller ones.

In May 1487, Ferdinand and Isabella began their siege of Mālaqa. After a fierce resistance, the city had to surrender. This victory was a bloody part of the war to conquer the Kingdom of Granada. But it meant the Christian religion was restored.

The Catholic Monarchs had already taken Ronda in 1485. Its leader, Hamet el Zegrí, refused to surrender and went to Mālaqa. He led the Muslim resistance there. The siege began on May 5, 1487. The Nasrid troops held out until August. Only the Alcazaba and Gibralfaro fortress still resisted.

The Catholic Monarchs besieged Mālaqa for six months. This was one of the longest sieges in the Reconquista. They cut off food and water supplies. This forced the Muslim defenders to surrender. On August 13, the Castilian army, over 45,000 strong, took the city. It was defended by 15,000 African mercenaries and Mālaqi warriors. King Ferdinand decided to make an example of those who resisted. He refused to grant them an honorable surrender. The people were punished by enslavement or execution. Only 25 families were allowed to stay as Mudéjar converts.

On August 18, Ali Dordux surrendered the citadel. But Gibralfaro had to be taken by force. Its defenders were sold as slaves, and Hamet el Zegrí was executed. The conquest of Mālaqa was a big blow to the Nasrid kingdom of Granada. It lost its main port.

The victorious Spanish soldiers were paid with land and property. Between 5,000 and 6,000 Christians from other parts of Spain moved to the province. About a thousand settled in the capital, now called Málaga. The city grew beyond its walls. New religious convents and neighborhoods like La Trinidad and El Perchel were created.

Early Modern Era: Changes and Challenges

The Mudéjars: Muslims Under Christian Rule

The word Mudéjar means "domesticated" in Arabic. It referred to Muslims who accepted Christian rule. Many Islamic communities survived in Málaga after the Reconquista. They were protected by agreements signed during the war. These agreements meant the Moors recognized the Catholic Monarchs' rule. They surrendered their fortresses and paid taxes. In return, their people, property, beliefs, laws, and customs were respected.

The Treaty of Granada protected religious freedoms for Muslims and Jews. But in the mid-16th century, they were forced to convert to Christianity. From then on, they were called Moriscos. This was because people suspected they weren't truly converted. In 1610, those who refused to convert were expelled from Málaga.

The layout of the Muslim city changed in the 16th century. This was to fit the needs of the Christian conquerors. A wide road was built to move goods from the main square to the port. The Cathedral of Málaga was built on the old mosque's foundations. New churches and convents outside the city walls attracted people. This led to new neighborhoods like La Trinidad and El Perchel.

Málaga's crafts included textiles, leather, clay, metal, and wood. The city became a shipping center for farm products from other kingdoms. It was also an entry point for goods into Andalusia.

16th–18th Centuries: Decline and Recovery

In 1585, Philip II ordered a new survey of the port. In 1588, he ordered a new dam and repairs to the Coracha. Over the next two centuries, the port expanded.

Trade, mostly by foreign merchants, was Málaga's main source of wealth in the 16th century. Wine and raisins were the main exports. Port improvements and new roads helped distribute Málaga's famous wines. Silk textiles were still important. The nobility gained more land by buying manors. Málaga's trade was important for the Spanish economy. But it suffered from corruption, like the sale of important government jobs.

From the 17th to the 18th century, the city declined. This was due to the expulsion of the Moors and floods from the Guadalmedina River. There were also several bad harvests. Other disasters included earthquakes and gunpowder explosions. Despite this, the population increased.

Málaga was important for Spain's foreign policy. It was the headquarters for military operations on the coast. This involved spending a lot on fortifying the harbor and building coastal towers. The loss of Gibraltar in 1704 made Málaga key to defending the Strait.

In the second half of the 18th century, Málaga solved its water problems. This was with the huge Aqueduct of San Telmo. After this, the city's economy recovered. The port expanded, work on the Cathedral restarted, and a new Customs building was built. Most people were still farmers and workers. But a new business-focused middle class emerged. This laid the groundwork for the 19th-century economic boom.

By the 18th century, Málaga's port was again one of the most important on the Mediterranean coast. After King Charles III allowed direct trade with Spanish American ports in 1778, port traffic grew. The population also grew a lot. Major city improvements were made. These included the Cathedral, the port, the Customs House, and new roads. In 1783, a bayfront boulevard, the Paseo de la Alameda, was built. By 1792, fancy mansions lined this new area.

19th Century: Industry and Upheaval

The 19th century was a difficult time for Málaga. It faced political, economic, and social problems. Spain's involvement in wars led to attacks on its ships. A deadly Yellow Fever epidemic killed over 26,000 people in Málaga. The city also suffered from the Peninsular War. There were conflicts between kings and liberals. Trade with the Americas ended, industries collapsed, and a disease destroyed the vineyards.

On May 2, 1808, people in Madrid rebelled against French occupation. When Málaga heard the news, its citizens also revolted. Guerrillas in the mountains fought fiercely.

The French faced strong resistance in Málaga. They left much of the city in ruins when they left. The war led to the adoption of the Spanish Constitution of 1812. This constitution was important for European liberalism. Málaga elected representatives to the national assembly. A new city council began reconstruction plans. The French were defeated in 1813. The next year, Ferdinand VII became King of Spain again. The war had damaged Spain's society and economy. This led to social unrest and political instability.

Ferdinand VII did not like the liberal Constitution of 1812. He ruled like an absolute monarch. His reign from 1814 to 1820 was a time of slow economy and political problems. Spain was devastated by war. Money was spent fighting for independence in Latin American colonies.

There were several attempts to bring back a liberal government. In 1820, an army revolted in Cádiz. When armies across Spain supported this, Ferdinand had to accept the liberal Constitution of 1812. This began the "Liberal Triennium" (1820–1823). Málaga was one of the independent towns that pushed for constitutional change.

The three years of liberal rule were full of plots by those who wanted absolute monarchy. Other European countries did not like the liberal government. In 1823, a French army invaded Spain. Ferdinand was restored as an absolute monarch.

During the "Ominous Decade" (1823–1833), liberals faced harsh punishment. In 1831, the liberal general José María Torrijos fought against Ferdinand VII. He wanted to restore the Constitution of 1812. He and his men were captured in Alhaurin de la Torre and executed on the beach. Torrijos is buried under an obelisk in his honor in Plaza de la Merced.

Málaga was a leader in Spain's Industrial Revolution. Its educated business class pushed for modern government. This made Málaga one of the most rebellious cities. The wealthy led uprisings for a more liberal system. This would encourage free business. In 1834, a revolt happened against the government. A year later, Málaga's governors were killed in an uprising.

In 1836, church properties were seized. This led to a new effort to modernize the city. Many old church buildings were torn down. New buildings, streets, and squares replaced them. For example, the convent of San Pedro de Alcantara became the Plaza del Teatro.

Economic Growth and Industry

The second half of the 19th century brought prosperity to Málaga. The economy grew with traditional trade and new industries. Málaga became an important European manufacturing center. The local government started urban renewal projects. Manuel Agustin Heredia's ironworks, La Constancia, became the country's leading iron foundry in 1834.

Trade grew a lot, attracting business people. Powerful families emerged from the merchant class. Some gained influence in national politics. Important families included the Larios and Lorings.

From 1834 to 1843, Spain had a liberal government. After that, the Moderate Party took control. They held power from 1843 to 1854. They used their power to achieve economic goals and keep order.

Isabella II of Spain became more active in government. But she was not popular. In the early 1850s, there was a railway boom. But politicians and the royal family were criticized for getting rich. This led to a revolution in 1854. A military coup happened in Madrid. This overthrew the government. The Progressive Party gained wide support and came to power. A new city council was elected. Taxes that the lower classes disliked were removed.

The growing economy needed more money. In 1859, Jorge Loring founded the private Bank of Málaga. It was the first to issue currency under a new law. The bank supported the growing steel and textile industries.

In 1862, Queen Isabel II visited Málaga. This was for the official opening of the Córdoba-Málaga railway. It also marked the opening of the Málaga railway station. The visit also aimed to improve political relations with Málaga and Andalusia.

Revolution and the First Spanish Republic

In 1868, a revolt called the Glorious Revolution happened. Generals Francisco Serrano and Juan Prim revolted against Isabella. They defeated her generals. Isabella was forced into exile. There was great excitement in Málaga when General Prim arrived.

However, two years of chaos followed. In 1870, Spain decided to have a king again. Amadeus of Savoy was chosen. He became King of Spain the next year. Amadeus was a liberal, but he faced the impossible task of uniting Spain's different political groups.

Amadeus found Spain ungovernable and left the country. A group of radicals, republicans, and democrats formed a government. On February 11, 1873, they declared the First Spanish Republic. This new republic immediately faced many challenges. The Carlists launched a violent uprising. There were calls for socialist revolution. The Catholic Church also opposed the republic.

Málaga recognized the new Republic on February 12. Pro-Republicans built barricades in the streets. The Cantonal Revolution spread across Spain in July. This uprising aimed to redistribute wealth and improve workers' lives. There were big disturbances in Málaga. On July 22, the city declared itself an independent "Federal Canton." The Customs House was attacked, and many files were burned. Fighting continued until General Manuel Pavía entered the city. He ended the Cantón de Málaga on September 19, 1873.

The chaos in Spain led military officers to plot against the Republic. They wanted to bring back Alfonso XII, Isabella II's son. On December 29, 1874, General Martínez Campos led a coup. This restored the monarchy.

Return of the Monarchy

After the chaos of the First Spanish Republic, Spaniards wanted stability. Isabella II had given up her throne to her son, Alfonso. He was crowned Alfonso XII of Spain. The Republican armies, who were fighting a Carlist uprising, pledged loyalty to Alfonso. The Republic was dissolved. Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, a trusted advisor to the king, became Prime Minister. The new king quickly put down the Carlist uprising.

A system of turnos was set up. Liberals, led by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, and conservatives, led by Cánovas, took turns controlling the government. Spain gained some stability and economic progress under Alfonso XII. His death in 1885 and Cánovas's assassination in 1897 destabilized the government. But the monarchy continued under King Alfonso XIII.

Málaga also saw social and economic changes. The wealthy became an oligarchy controlling local politics. A working class of industrial laborers grew in the factories. These large factories led to the growth of a workers' suburb. This area was separate from the wealthy residential areas. The city's population kept growing, needing more public services.

Monasteries were not just religious centers. They also preserved Málaga's culture. Their locations affected the city's growth outside the old center. In the west, industrial activity shaped the landscape. In the east, villas and hotels appeared. When old church buildings were seized and torn down, the city had new chances to grow.

Communications improved with new railway lines. These transported raw materials and industrial products. Jorge Loring and Joaquin de la Gandara founded the Andalusian Railway Company in 1877. This company owned most of the rails in Andalusia. This helped create a common regional market for trade.

Málaga had significant economic development in the first half of the 19th century. By 1850, it was second in industrial production in Spain, after Barcelona. Textile and steel industries led to other factories. These included soap, paint, and fish processing. Breweries, timber mills, potteries, brickworks, and tanneries also grew. This led to building a rail network between Córdoba and Málaga. The city got public gas lighting in 1852. Electric power was introduced in 1897. A public tram service began in 1881, using horses. In 1901, electric power replaced the horses.

In 1880, the city council started a project to build Calle Marqués de Larios. This was in honor of the textile industrialist Manuel Domingo Larios. The street opened in 1890. This was the start of modernizing the city.

Workers' organizations grew, and labor conflicts increased. The first socialist unions in Málaga started in 1884. Rafael Salinas Sánchez, known as the "apostle" of socialism, founded a workers' athenaeum. He was active in unions and was exiled for two years. In 1884, he founded the Agrupación Socialista de Málaga. More than 2,000 people attended a socialist rally in 1890.

Salinas helped organize local chapters of the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT). This is the General Union of Workers. They held their Third National Congress in Málaga in 1892. They made plans to improve working conditions in factories. But Salinas was jailed for supporting workers. The Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) and the UGT faced repression. There were frequent clashes between workers and employers.

Economic Crisis and Decline

The economic boom in Málaga ended in 1880. Importing coal for steel production became too expensive. This made Málaga's foundries less competitive. The economic crisis of 1893 forced the La Constancia iron foundry to close. The sugar industry also collapsed. The phylloxera blight destroyed the province's vineyards. Farms were abandoned, leading to deforestation and more floods.

The crisis hit the most vulnerable people hardest. This included farm laborers, small landowners, industrial workers, and artisans. Tens of thousands of people from Málaga moved overseas for better opportunities.

The crisis led many to look for new ways to make a living. Some thought about tourism. Years passed before efforts were made to develop Málaga as a tourist spot. In 1897, a group of Málaga businessmen founded a society to promote tourism. They saw its potential to bring wealth. Their campaigns promoted Málaga's mild climate. This attracted enough tourists to help ease the economic problems.

20th Century: Modernization and Conflict

The economic problems from the late 19th century continued into the early 20th century. Local political bosses, called caciques, controlled Andalusia. Monarchist parties took turns governing, but the recession worsened. The economy was depressed, there was social conflict, and the government was weak. This made oligarchy and caciquism key features of the province. In this situation, republican and labor movements gained new support.

The early 20th century was a time of change in Málaga. Agriculture became the main economic sector. Industry slowly declined, and trade went up and down. Society was still largely uneducated. Wealthy families controlled politics and the economy. Primary education lacked funding and schools. Higher education was limited. Málaga faced the new century with economic depression and social unrest. Republicans and labor movements found common ground.

The city's trade was still important, but less strong than before. Infrastructure improved with a tram line and commuter railways. A hydroelectric plant opened. In 1919, Málaga Airport was created. It was a stop on the first airline route in Spain.

Málaga During World War I

Spain was neutral in World War I. This allowed it to supply materials to both sides. This brought a huge economic boom. Exports of farm products, minerals, textiles, and steel grew. Business profits soared. But workers' wages did not keep up with inflation. Their living standards actually decreased. City workers kept pushing for higher wages.

"The 1917 Crisis" refers to events in Spain in the summer of 1917. There were three movements challenging the government. These included military, political, and social movements.

Spain's economy suffered after the war. Foreign demand for products fell. This hurt agriculture, industry, and trade. Workers demanded protection as prices fell. Employers wanted to cut costs and lower wages. But workers refused.

Factories closed, unemployment rose, and wages fell. The capitalist class fought against unions, especially the CNT. Lockouts became common. Assassins were hired to kill union leaders. Many anarchists were murdered. Anarchists responded with assassinations, including Prime Minister Eduardo Dato Iradier.

The influenza pandemic in 1918 and a major economic slowdown hit Spain hard. The country went into debt. Social conflict increased. Strikes and land occupations happened in cities and the countryside. The government seemed unable to solve unemployment, strikes, and poverty. Socialists and anarchists pushed for big changes.

Socialist groups became more influential in Málaga from 1909. Anarchism also gained popular support. The "Bolshevik triennium" (1918–1920) saw many strikes. This was due to news of the Russian Revolution and bad economic conditions. Málaga and Seville provinces had the strongest CNT presence.

Dictatorship of Primo de Rivera

On September 13, 1923, General Miguel Primo de Rivera became dictator. He promised to fix problems created by politicians. He also wanted to modernize the economy and help the working class.

Primo de Rivera's planners built infrastructure. Hydroelectric dams provided water and electricity. Spain had few cars, but by 1930, it had a network of roads. His regime improved railroads, helping the iron and steel industry. Public works in Málaga included planning the Ciudad Jardín district.

Between 1923 and 1927, foreign trade tripled. Primo de Rivera improved relations with unions and did public works. But he failed to win over the middle classes. He supported landowners, so he didn't make big farming reforms. He also limited human rights in Catalonia.

Population records show fewer people in Málaga province due to emigration. Most people went to the Americas. Republican parties regrouped, and socialist worker movements grew stronger. Even with limited rights, an intellectual movement grew in Málaga. This influenced the city's culture.

In 1925, poets Emilio Prados and Manuel Altolaguirre became editors for the Sur printing house in Málaga. Sur published most of the work of the Generation of '27. Their editing brought them international fame. In 1926, they founded Litoral magazine. It was one of the most important literary magazines of the 1920s.

Federico García Lorca's Canciones was published in 1927. It was a highlight of his early poetry.

Writers and intellectuals met at the Café de Chinitas (1857–1937). This famous cabaret was where the best flamenco singers performed in the 1920s.

Between Dictatorship and Republic

The economic boom ended. Spaniards became unhappy with the dictatorship. Critics blamed rising inflation on government spending. In 1929, there was a bad harvest. Spain imported more than it exported. The Wall Street crash hurt foreign trade. Old problems returned to Spain's politics and economy. Unhappiness spread. When King Alfonso and the army no longer supported him, Primo de Rivera resigned on January 26, 1930.

The political mood in Málaga was tense. Republicans reorganized and worked with socialists. Monarchist groups struggled to find a candidate. Anarchist and Communist parties organized protests and strikes. They fought for better conditions for workers.

The king had to ask Primo de Rivera to resign. People were disgusted with the king's involvement in the dictatorship. In the municipal elections of April 1931, urban populations voted for republican parties. The king fled the country, and a republic was established.

Second Spanish Republic

After the Second Spanish Republic was declared on April 14, 1931, there were riots across Spain. Crowds burned convents, churches, and religious buildings. This event was called la quema de conventos (the burning of the convents). When news reached Málaga, mobs attacked the Jesuits' residence and the Episcopal Palace. The chaos lasted for two days.

Málaga was hit hardest by the quema. Much of its religious, artistic, cultural, and historical heritage was destroyed. Many buildings were damaged or lost. Priceless historical records, religious images, old paintings, and libraries were burned. This included masterpieces by sculptor Pedro de Mena.

In 1933, Málaga elected the first Communist Party member to Congress. With many active socialists, anarchists, and communists, Málaga became known as "Red Málaga." But Catholics, liberals, and conservatives were still part of local politics.

Spanish Civil War: A Tragic Conflict

Spanish politics became very divided in the 1930s. The left-wing wanted class equality, land reform, and less church power. The right-wing, mainly the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right (CEDA), disagreed. The first two governments of the Republic were center-left. Economic problems and changing governments led to unrest. In 1933, CEDA won elections. An armed workers' uprising in 1934 was put down forcefully. This energized political movements across Spain. New anarchist, reactionary, and fascist groups appeared. The left united in the Popular Front and won the 1936 elections.

However, this coalition was weakened by revolutionary groups and anti-democratic far-right groups. Political violence started again. The Spanish Civil War began after generals, led by José Sanjurjo, declared opposition to the elected government. The rebel coup was supported by conservative, religious, and fascist groups.

The Battle of Málaga

On July 17, 1936, General Francisco Franco led the colonial army from Morocco to attack Spain. Other forces also mobilized. Franco wanted to seize power immediately. But resistance from Republicans led to a long civil war. Soon, much of the south and west was under Nationalist control.

The Siege of the Alcázar at Toledo was a turning point. The Nationalists won after a long siege. Republicans managed to hold out in Madrid despite an attack in November 1936.

The Battle of Málaga was a big attack in February 1937. Nationalist and Italian forces, led by General Queipo de Llano, aimed to take Málaga province from the Republicans. Moroccan soldiers and Italian tanks helped. The Spanish Republican Army was completely defeated. Málaga surrendered in less than a week, on February 8.

The occupation of Málaga led to many civilians and soldiers fleeing on the road to Almería. They were attacked by Franco's air force, navy ships, tanks, and artillery. Hundreds died. This event is known as the "Málaga-Almería road massacre".

The Nationalists continued to gain ground. The north, including the Basque country, fell in late 1937. The Aragon front collapsed. The Battle of the Ebro in 1938 was the Republicans' last desperate attempt. When it failed, and Barcelona fell in early 1939, the war was clearly over. Madrid fell in March 1939.

The war cost between 300,000 and 1,000,000 lives. It ended with the Republic's destruction. Francisco Franco became dictator of Spain. Franco combined all right-wing parties. He banned left-wing and Republican parties and unions. The war was brutal, with massacres on both sides. After the war, many thousands of Republicans were imprisoned. Up to 151,000 were executed between 1939 and 1943.

Málaga Under Franco's Dictatorship

During Franco's rule, Spain was officially neutral in World War II. It was mostly isolated from the outside world. Under a right-wing military dictatorship, political parties were banned, except for the official party. Labor unions and all opposing political activity were forbidden.

Under Franco, Spain tried to get Gibraltar back from the UK. It gained some support at the United Nations. In the 1960s, Spain restricted access to Gibraltar. The border was closed in 1969 and fully reopened in 1985.

Spanish rule in Morocco ended in 1967. Spain gradually gave up its remaining African colonies. Spanish Guinea became independent in 1968. The Moroccan area of Ifni was given to Morocco in 1969.

The later years of Franco's rule saw some economic and political changes. This included the start of the tourism industry. Spain began to catch up economically with other European countries.

Franco ruled until his death on November 20, 1975. Control was then given to King Juan Carlos. Before Franco's death, the Spanish state was in a crisis. King Hassan II of Morocco took advantage of this. He ordered the 'Green March' into Western Sahara, Spain's last colony.

Málaga saw huge population and economic growth. This was due to the tourism boom on the Costa del Sol from 1959 to 1974. The name "Costa del Sol" was created to market Málaga's coast to foreign tourists. Historically, people lived in fishing villages or inland "white villages." The area was developed for international tourism in the 1950s. It has been popular ever since. Many people moved from towns in the province to the capital. Others moved from Málaga to northern Spain and other European countries.

The "Spanish miracle" was fueled by people moving from rural areas. This created a new class of industrial workers. The economic boom led to rapid, unplanned building around Costa del Sol cities. This was to house new workers. Some cities kept their historic centers. But most were changed by commercial and residential developments. Long stretches of beautiful coastline were also changed by mass tourism.

The University of Málaga (UMA) was founded on August 18, 1972. It brought together existing higher education centers. The Faculty of Medicine was created later.

Teatinos Campus is the largest UMA campus. It holds most university buildings. These include engineering, medicine, science, philosophy, psychology, and law. The main library is also there. The campus is still expanding.

On September 27, 1988, the Andalusian Parliament approved the separation of Torremolinos. It became its own municipality. This took away ten percent of Málaga city's population. Many people in Málaga thought this was unfair. But it responded to the wishes of thousands of Torremolinos residents. Málaga city lost population and tax revenue.

The Andalusia Technology Park (PTA) opened in 1992.

21st Century: Modern Málaga

Málaga's Metro began with plans in the late 1990s. The goal was to create a light rail network to ease traffic. In 2001, a study proposed four lines. The first two lines are still being built as of 2012.

Since 1998, the Port of Málaga has been renovated and expanded. Major projects are changing the port's image. The total goods traffic was over 2.3 million metric tonnes in 2015.

Cruise shipping is now a key industry at the port. It drives much investment in Málaga. In 2012, over 650,000 passengers visited the city on cruise ships. The regular line between Málaga and Melilla moved over 300,000 passengers. The cruise industry is developing with a new passenger terminal and a port museum. A commercial marina for super-yachts is also planned. The quays are connected by roads and railway lines.

AVE (Alta Velocidad Española), Spain's high-speed rail service, opened the Córdoba-Málaga line on December 24, 2007. This 155 km line connects Málaga and Córdoba. It is designed for speeds of 300 km/h. The line goes through mountains, so many viaducts and tunnels were needed.

Málaga Airport (Aeropuerto de Málaga) is the fourth busiest airport in Spain. It is important for Spanish tourism. It is the main international airport for the Costa del Sol. It offers many international destinations. Málaga Airport is one of the oldest Spanish airports still in its original location. The Málaga Plan aims to handle more passengers. It includes a new terminal, car park, and airfield extension.

A large convention hall, the Trade Fairs and Congress Center, opened in 2003.

The Club Málaga Valley e-27 is an initiative by politicians and business leaders. They want to develop strategies for Málaga in information technology.

The Picasso Museum (Museo Picasso Málaga) opened in 2003. It is in the Buenavista Palace. It has 285 works donated by Picasso's family.

The Museo Thyssen Carmen opened in 2011. It houses 19th and 20th-century Spanish paintings.

The Contemporary Art Center of Málaga (CAC) was created by the city council. It aims to spread appreciation for modern art. The center is in the former Wholesalers' Market.

The Málaga Film Festival is the most important festival for Spanish cinema. It is held annually in April.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Málaga para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Málaga para niños

- Timeline of Málaga

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |