History of road transport facts for kids

The history of road transport began when humans and their pack animals started making paths. These early trails helped people move goods and travel from place to place.

Contents

Ancient Roads and Paths

Long ago, people didn't need special roads in open areas. The first paths were likely made better at places where people crossed rivers (called fords), went through mountain passes, or walked through swamps. People would clear trees and big stones to make these paths easier to use.

As trade grew, these dirt paths were often made flatter or wider for people and animals. Some of these simple paths became large networks. They helped with communication, trade, and managing big areas. For example, the Inca Empire in South America and the Iroquois Confederation in North America used such paths very well, even though they didn't have wheels.

At first, people carried goods on their backs or heads. But then, they started using pack animals like donkeys and horses during the Stone Age. The first tool for dragging loads was probably the travois. This frame likely appeared in Eurasia after people started using oxen to pull plows. Around 5000 BC, sleds were invented. They were harder to build but easier to move on smooth ground.

Pack animals, people riding horses, and oxen pulling travois or sleds needed wider paths. So, by 5000 BC, roads like the Ridgeway in England were built along high ground to avoid rivers and muddy areas. In central Germany, these "ridgeways" were the main long-distance roads until the mid-1700s.

Early Paved Streets

Some of the first paved streets were found in human settlements around 4000 BC. These were in cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation in modern-day Pakistan, like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. The roads in these towns were straight and long, crossing each other at right angles.

How Wheeled Transport Changed Roads

Wheels likely first appeared in ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia) around 5000 BC. They might have been used for making pottery before transport. Their first use for moving things might have been attached to travois or sleds to make them easier to pull.

The first simple two-wheel carts, probably developed from travois, were used in Mesopotamia and northern Iran around 3000 BC. Two-wheel chariots appeared around 2800 BC. They were pulled by onagers (wild donkeys). Heavy four-wheeled wagons developed around 2500 BC. These were only good for oxen to pull and were used mainly where crops were grown, especially in Mesopotamia.

Two-wheeled chariots with spoked wheels were likely developed around 2000 BC by the Andronovo culture in southern Siberia and Central Asia. Around the same time, the first simple harness was invented, which allowed horses to pull things.

Wheeled transport meant that better roads were needed. Natural materials often aren't strong enough for wheeled vehicles, especially when wet. So, in cities, people started building stone-paved streets. The first paved streets seem to have been built in Ur in 4000 BC.

Corduroy roads (roads made of logs laid across the path) were built in Glastonbury, England in 3300 BC. Brick-paved roads were built in the Indus Valley Civilisation around the same time. By 2000 BC, better tools for cutting stone were available in the Middle East and Greece, allowing local streets to be paved.

Around 2000 BC, the Minoans built a 50 km (about 31 miles) paved road on Crete. This road had side drains, a thick pavement of sandstone blocks held together with clay-gypsum mortar, and a top layer of basalt flagstones. It even had separate shoulders (sides). This road was very advanced, even better than some later Roman roads.

In 500 BC, Darius the Great started building a large road system for Persia. This included the famous Royal Road, which was one of the best highways of its time. Mail carriers could travel 2,699 km (about 1,677 miles) in just seven days because of its high quality.

From 268 BCE to 22 BCE, Ashoka built roads, water wells, rest houses, and hospitals for people and animals across the Indian subcontinent. He also planted trees for travelers. The Maurya Empire built the Grand Trunk Road, which was about 2,000 miles long and stretched from modern-day Bangladesh to Peshawar in Pakistan.

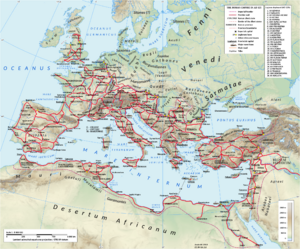

Roman Roads: Built to Last

When the Roman Empire grew, armies needed to move quickly. Existing roads were often muddy, which slowed down large groups of soldiers. To fix this, the Romans built amazing roads. These roads had deep layers of crushed stone underneath. This kept them dry, as water would drain away instead of turning the soil into mud. Roman soldiers could march very fast on these roads, and some are still used thousands of years later.

On busy routes, there were extra layers, including six-sided capstones or pavers. These reduced dust and made it easier for wheels to move. The pavers allowed Roman chariots to travel very quickly, helping with communication across the Roman provinces. Farm roads were often paved first near towns to keep produce clean. Early forms of springs and shocks were added to horse-drawn transport to reduce bumps, as the original pavers weren't perfectly smooth.

Roads in the Middle Ages

In medieval Europe, Roman roads fell apart because there weren't enough resources or skills to fix them. However, many parts continued to be used. Some of their paths are still used today, like parts of England's A1. Before the 1200s, cities didn't have organized street networks, just changing footpaths. With the invention of the horse harness and wagons with turning front axles, city street networks became more stable.

In the medieval Islamic world, many roads were built across the Arab Empire. The most advanced roads were in Baghdad, Iraq. These were paved with tar in the 700s. Tar came from oil fields in the region.

Early Modern Road Building

As countries grew and became richer, especially during the Renaissance, new roads and bridges were built. These often copied Roman designs. But there wasn't much new invention in road building until the 1700s.

In 18th century West Africa, the Ashanti Empire had a network of well-kept roads. These connected the capital city with other areas. After a lot of road building by the kingdom of Dahomey, toll roads were set up. People had to pay yearly taxes based on the goods they carried. The Royal Road was built in the late 1700s by King Kpengla.

Between 1725 and 1737, General George Wade built 250 miles (400 km) of roads and 40 bridges in Britain. This helped Britain control the Scottish Highlands. He used Roman road designs with large stones at the bottom and gravel on top. However, these roads were poorly planned and steep, making them hard to use.

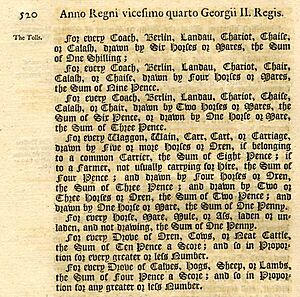

Toll Roads: Paying for Better Paths

In Tudor times, local parishes were in charge of roads. In 1656, a parish in Hertfordshire asked Parliament for help to fix their part of the Great North Road. Parliament passed a law allowing local officials to put up toll gates. People had to pay to use the road, and the money was used to fix it. This toll gate was the first effective one in England.

The first system with special trustees (not just local officials) was set up in 1707. This was for a section of the London-Chester road. The idea was that trustees would manage money from different parishes and add tolls from users. This money would then be used to maintain the main highway. This became the model for many more "turnpikes" (toll roads).

By the early 1700s, parts of the main roads leading into London were controlled by individual turnpike trusts. More trusts were created in the 1750s for cross-country routes. By 1825, about 1,000 trusts managed 18,000 miles (29,000 km) of road in England and Wales.

These trusts gained more powers. From the 1750s, they had to put up milestones showing distances between towns. Road users had to follow rules, like driving on the left and not damaging the road. Trusts could even charge extra tolls in summer to water the roads and reduce dust. Parliament also made rules about wheel widths, as narrow wheels caused more damage.

The quality of early turnpike roads varied. Road building slowly improved, thanks to people like John Metcalf. British builders learned to use clean stones for the surface and avoid dirt or clay to make roads last longer.

In the United States, turnpikes were usually built by private companies. They often followed or replaced existing trade routes. They hoped that better roads would attract enough traffic to make money. Plank roads, made of wooden planks, were popular because they greatly reduced resistance and solved the problem of getting stuck in mud.

New Road Designs

John Metcalf's Methods

The first professional road builder during the Industrial Revolution was John Metcalf. He built about 180 miles (290 km) of turnpike roads, mostly in northern England, starting in 1765. Metcalf believed a good road needed strong foundations, good drainage, and a smooth, curved surface. This curved surface allowed rainwater to drain quickly into ditches.

He understood that rain caused most road problems. He even figured out how to build a road across a bog using bundles of heather and gorse as foundations. This made him famous as a road builder.

Trésaguet's Scientific Approach

Pierre-Marie-Jérôme Trésaguet is known for creating the first scientific approach to road building in France. In 1775, he wrote about his method, which became common practice in France. It involved a layer of large rocks covered by a layer of smaller gravel. The lower layer helped spread the weight of the road and traffic evenly, protecting the ground. The top layer provided a smooth surface and protected the large stones below.

Trésaguet also understood the importance of drainage, using deep side ditches. He started a system of continuous maintenance, where a road worker was in charge of keeping a section of road in good condition.

Telford's Engineering Advances

The engineer Thomas Telford made big improvements in building new roads and bridges. His method involved digging a large trench and setting a foundation of heavy rock. He designed his roads to slope downwards from the center (a "crown slope"). This allowed water to drain, which was a major improvement over Trésaguet's work. The surface was made of broken stone.

Telford also improved how stones were chosen based on thickness, traffic, and slopes. In his later years, Telford rebuilt parts of the London to Holyhead road. His work on the Holyhead Road in the 1820s cut the travel time for the London mail coach from 45 hours to just 27 hours. The best mail coach speeds went from 5-6 mph (8–10 km/h) to 9-10 mph (14–16 km/h).

McAdam's Modern Roads

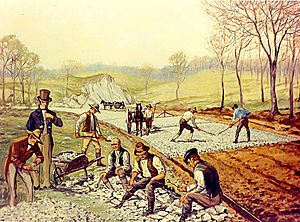

Another Scottish engineer, John Loudon McAdam, designed the first truly modern roads. He developed an inexpensive paving material using soil and stone aggregate (called macadam). His method was simpler than Telford's but very effective. He found that huge rock foundations were not needed. He believed the natural soil could support the road and traffic, as long as it was covered by a strong surface layer that protected the soil from water and wear.

Unlike other builders, McAdam laid his roads as level as possible. His 30-foot (9-meter) wide road only needed a three-inch (7.5 cm) rise from the edges to the center. This slight curve and raising the road above the water table helped rainwater run off into ditches.

The size of the stones was key to McAdam's theory. The lower 200 mm (8 inches) of road thickness used stones no larger than 75 mm (3 inches). The top 50 mm (2 inches) layer used stones limited to 20 mm (0.8 inches) in size. Workers even checked stone size by seeing if it would fit into their mouth! The 20 mm stone size was important because the stones needed to be much smaller than the 100 mm (4 inches) width of iron carriage wheels.

McAdam believed that stones should be broken by people sitting down and using small hammers. No stone should be larger than six ounces (170 grams). He said the road's quality depended on how carefully the stones were spread, one shovelful at a time.

McAdam insisted that nothing that would absorb water or be affected by frost should be put into the road. He also said nothing should be laid on the clean stone to bind it. He thought the traffic itself would cause the broken stones to interlock, forming a solid surface that could handle weather and traffic. His roads turned out to be twice as strong as Telford's.

Even though McAdam didn't want filler materials, builders started adding smaller stones, sand, and clay between the main stones. They noticed these roads became even stronger. Macadam roads were built widely in the United States and Australia in the 1820s, and in Europe in the 1830s and 1840s. These roads were good for horses and carriages, but they were very dusty and could erode easily in heavy rain.

Modern Roads and Highways

The Good Roads Movement happened in the United States from the late 1870s to the 1920s. People who wanted better roads, like bicyclists from the League of American Wheelmen, turned local efforts into a national movement. Outside cities, roads were just dirt or gravel, turning into mud in winter and dust in summer. Early supporters pointed to Europe, where national and local governments supported road building. The movement's main goal was to teach people how to build roads in rural areas. This would help rural communities get the social and economic benefits that cities enjoyed from railroads, trolleys, and paved streets. Bicycles, even more than traditional vehicles, benefited from good country roads.

Later, macadam roads couldn't handle faster motor vehicles. Methods to stabilize roads with tar go back to at least 1834. This involved spreading tar on the base, adding a macadam layer, and then sealing it with a mix of tar and sand. Tar-grouted macadam was used before 1900. Although tar was known in road building in the 1800s, it wasn't used widely until cars became popular in the early 1900s.

Modern tarmacadam was patented by British engineer Edgar Purnell Hooley. He noticed that spilled tar on the road kept dust down and made a smooth surface. He patented "tarmac" in 1901. Hooley's patent involved mixing tar and stone before laying it down, then compacting it with a steamroller. The tar was improved by adding small amounts of Portland cement, resin, and pitch.

Controlled-Access Highways: Faster Travel

The first modern controlled-access highways developed in the early 1900s. The Long Island Motor Parkway in New York, opened in 1908, was the world's first limited-access road built by a private company. It had many modern features, like banked turns, guard rails, and reinforced concrete tarmac. However, traffic could still turn left and cross oncoming traffic, so it wasn't a true "freeway" as we know it today.

Modern controlled-access highways started in the early 1920s. This was because more and more people were using automobiles. There was a demand for faster travel between cities. These early high-speed roads were called "dual highways." They have been updated and are still used today.

Italy was the first country to build controlled-access highways just for fast traffic and motor vehicles. The Autostrada dei Laghi ("Lakes Motorway"), connecting Milan to Lake Como and Lake Maggiore, opened in 1924. This motorway, called autostrada, had only one lane in each direction and no interchanges (places where roads cross or join). The Bronx River Parkway in North America was the first road to use a median strip to separate opposing lanes. It was also built through a park, and crossing streets went over bridges.

In Germany, construction of the Bonn-Cologne Autobahn began in 1929 and opened in 1932. In Canada, the first road with semi-controlled access was The Middle Road between Hamilton and Toronto. It had a median divider and the country's first cloverleaf interchange. This highway became the Queen Elizabeth Way, which opened in 1937. A decade later, the first section of Highway 401 opened. It has since become North America's busiest highway.

The word freeway was first used in February 1930 by Edward M. Bassett. Bassett said roads should be classified into three types: highways, parkways, and freeways. In his system, property owners next to highways had rights to light, air, and access. But they did not have these rights for parkways and freeways. Parkways were for recreation, while freeways were for movement. So, a freeway was originally a public land strip for movement where nearby property owners had no rights of light, air, or access.

|

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |