Leatherback sea turtle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Leatherback sea turtle |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, United States Virgin Islands | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | Dermochelyidae |

| Subfamily: | Dermochelyinae |

| Genus: | Dermochelys Blainville, 1816 |

| Species: |

D. coriacea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761)

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) is the biggest of all living turtles. It is also the heaviest reptile that is not a crocodilian. These amazing turtles can grow up to 2.7 metres (8 ft 10 in) long and weigh as much as 500 kilograms (1,100 lb).

You can easily tell leatherbacks apart from other sea turtles because they don't have a hard, bony shell. Instead, their carapace (the top part of their shell) is covered by tough, flexible, leather-like skin. This is how they got their name! Leatherback turtles live all over the world, but different groups of them live in specific areas. Overall, this species is considered vulnerable, meaning it needs protection. Some groups are even critically endangered, facing a very high risk of disappearing.

Contents

Understanding Leatherback Turtles

What's in a Name?

The leatherback sea turtle is the only living species in its group, called Dermochelys, and its family, Dermochelyidae. The scientific name, Dermochelys coriacea, means "Leathery Skin-turtle." This name perfectly describes their unique shell.

The species was first named Testudo coriacea in 1761. Later, in 1816, a French zoologist named Henri Blainville created the term Dermochelys. The turtle was then reclassified as Dermochelys coriacea.

How Leatherbacks Evolved

Modern leatherback turtles look very similar to their ancient relatives. These relatives first appeared over 110 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. Leatherbacks are related to the family Cheloniidae, which includes the other six types of sea turtles we see today. Scientists believe these two families separated about 49 to 70 million years ago.

Body Features and How They Work

Amazing Anatomy

Leatherback turtles have a very streamlined body, shaped like a teardrop. This helps them move easily through the water. They have large front flippers that propel them forward. These flippers are the biggest of any sea turtle, sometimes growing up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) in large adults! Unlike other turtles, leatherbacks don't have claws on their flippers.

Their most special feature is their shell. Instead of hard scutes (the plates on a typical turtle shell), they have thick, leathery skin with tiny bones embedded in it. This flexible skin might help them adjust their fat layers. This helps them stay warm during deep dives and gives them energy for long journeys. Seven clear ridges run along the length of their back.

Leatherbacks are dark grey or black on top, with white spots. Their underside is lighter, which helps them blend in with the ocean from above and below. This is called countershading. Instead of teeth, they have sharp points on their upper lip. They also have backward-pointing spines in their throat. These spines help them swallow food and prevent their prey from escaping.

Adult leatherbacks usually measure between 1–1.75 m (3.3–5.7 ft) in shell length and weigh from 250 to 700 kg (550 to 1,540 lb). The largest verified leatherback ever found was 213 cm (6.99 ft) long and weighed 650 kg (1,433 lb). When they hatch, baby leatherbacks are tiny, only about 61.3 mm (2.41 in) long and weighing around 46 g (1.6 oz).

Built for Deep Dives

The leatherback's unique shell helps it handle the extreme pressure of deep ocean dives. Its soft, leathery skin covers small, bone-like pieces called osteoderms. These pieces are connected in a way that allows the shell to be flexible. This flexibility is important because their lungs expand when they breathe air and contract when they dive deep. This special design helps their shell withstand the immense pressure at depths of up to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft).

Staying Warm and Moving Fast

Leatherbacks are special among reptiles because they can keep their bodies warm using heat from their own metabolism. They are very active and swim almost constantly, which creates a lot of muscle heat. Combined with their insulating fat and large size, they can stay much warmer than the cold water around them. Adult leatherbacks have been found with body temperatures 18 °C (32 °F) warmer than the ocean water.

These turtles are also incredible divers. They can dive deeper than almost any other marine animal, reaching depths of 1,280 m (4,200 ft). Most dives last 3 to 8 minutes, but some can be as long as 30 to 70 minutes! They are also known as the fastest-moving reptiles, capable of swimming at speeds up to 35.28 km/h (21.92 mph).

Where Leatherbacks Live Around the World

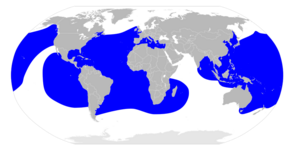

The leatherback turtle lives in oceans all over the globe. They have the widest distribution of all sea turtle species. You can find them as far north as Alaska and Norway, and as far south as New Zealand and Cape Agulhas in Africa. They live in all tropical and subtropical oceans, and even venture into the Arctic Circle.

Scientists have identified three main groups of leatherbacks based on their genetics: those in the Atlantic Ocean, the eastern Pacific Ocean, and the western Pacific Ocean. There are also leatherback populations in the Indian Ocean, but they haven't been studied as much.

Sadly, the number of nesting females has dropped significantly. In 1980, there were an estimated 115,000 nesting females. Recent estimates suggest only 26,000 to 43,000 females nest each year.

Atlantic Ocean Leatherbacks

Atlantic leatherbacks live across the entire Atlantic Ocean. They travel to colder waters to find their favorite food, jellyfish, which helps them spread out widely. However, they only nest on a few beaches on both sides of the Atlantic. Important nesting sites include Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana in South America, Antigua and Barbuda, and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean. In Africa, Mayumba National Park in Gabon hosts the largest nesting population, with nearly 30,000 turtles visiting its beaches each year. A few hundred also nest annually on the eastern coast of Florida.

Leatherbacks are rarely seen in the Mediterranean Sea. However, one was spotted in the Bosphorus strait in 2024, and another was found on a Black Sea beach in Turkey in 2025.

Pacific Ocean Leatherbacks

Pacific leatherbacks are divided into two main groups. One group nests in Papua, Indonesia, and the Solomon Islands. They then travel across the Pacific to feed along the coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington in North America. The other group nests in Mexico, Panama, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, as well as eastern Australia. They feed in waters along the western coast of South America.

The WWF estimates that only about 2,300 adult female Pacific leatherbacks remain. This makes them the most endangered group of marine turtles.

South China Sea Leatherbacks

There was once a large group of leatherbacks that nested in Malaysia. Sadly, this group has almost disappeared. The beach of Rantau Abang in Terengganu, Malaysia, used to have the most nests in the world, with 10,000 nests per year. A big reason for this decline was people collecting and eating their eggs. Conservation efforts started in the 1960s, but they accidentally caused problems. The eggs were incubated at high temperatures, which scientists later learned determines the sex of the hatchlings. It's thought that almost all the baby turtles from these artificial sites were female. In 2008, only two turtles nested at Rantau Abang, and their eggs were not fertile.

Indian Ocean Leatherbacks

Not much research has been done on leatherbacks in the Indian Ocean. However, nesting populations are known in Sri Lanka and the Nicobar Islands. Scientists believe these turtles form their own unique group.

Life Cycle of Leatherback Turtles

Where They Live and What They Eat

Leatherback sea turtles mostly live in the open ocean. They follow their jellyfish prey, diving deeper during the day and staying in shallower waters at night when jellyfish rise. This means they often hunt in very cold waters. One turtle was seen hunting in water as cold as 0.4 °C (32.7 °F)! After these cold dives, the turtle would return to warmer surface waters (around 17.5 °C (63.5 °F)) to warm up. Leatherbacks can dive deeper than 1000 meters, which is deeper than almost any other diving animal except for some whales.

When it's time to lay eggs, they prefer beaches that face deep water and avoid areas with coral reefs.

What Leatherbacks Eat

Adult leatherback turtles eat almost only jellyfish. By eating so many jellyfish, they help keep jellyfish populations in check. This is important because jellyfish often eat young fish, which humans later catch for food. Leatherbacks also eat other soft-bodied creatures like siphonophores, salps, and squid.

Pacific leatherbacks travel about 6,000 mi (9,700 km) from their nesting sites in Indonesia to eat jellyfish off the coast of California. During these long trips, small fish called remoras sometimes attach to the turtles for a free ride.

A big danger for leatherbacks is plastic bags floating in the ocean. They often mistake these bags for jellyfish, their favorite food. It's estimated that about one-third of adult leatherbacks have eaten plastic. Plastic pollution can block their digestive system and make them sick. It can also make them feel full without getting any nutrients, which affects their growth and ability to reproduce.

How Long Do They Live?

Scientists don't know exactly how long leatherback turtles live. Some estimates say "30 years or more," while others suggest "50 years or more," and some even guess over 100 years. In 2020, researchers used genetic information to estimate the natural lifespan of a leatherback turtle to be about 90.4 years.

Reproduction and Offspring

Predators of Leatherback Turtles

Leatherback turtles face many dangers when they are young. Their eggs can be eaten by animals like ghost crabs, monitor lizards, raccoons, and dogs. Baby turtles trying to reach the ocean are hunted by shorebirds and raptors. Once in the ocean, young leatherbacks can be prey for cephalopods, sharks, and large fish.

Adult leatherbacks are so big that they have fewer natural predators. However, very large marine predators like killer whales, great white sharks, and tiger sharks can sometimes hunt them. Nesting females have also been attacked by jaguars and saltwater crocodiles. Adult leatherbacks have even been seen chasing away sharks that tried to bite them!

Mating and Nesting

Mating happens in the ocean. Male leatherbacks never leave the water once they enter it. Females, however, come to land to nest. A female might lay up to 10 clutches of eggs in one nesting season, with about nine days between each nesting event.

Leatherbacks choose beaches with soft sand because their softer shells can be easily damaged by hard rocks. They nest at night when it's cooler and there's less risk from predators. The dark forest behind the beach and the brighter ocean help the females find their way. They nest towards the dark forest and then return to the light of the ocean.

An average clutch has about 110 eggs, but only about 85% of them are viable (meaning they can develop). After laying her eggs, the female carefully covers the nest with sand to hide it from predators. Sadly, about half of the eggs laid don't even develop into hatchlings.

Development of Offspring

The eggs hatch in about 60 to 70 days. The temperature of the nest determines if the baby turtles will be male or female. After dark, the hatchlings dig their way to the surface and walk to the sea. Scientists have found that the temperature during incubation can affect the size and shape of the baby turtles. Higher temperatures can lead to smaller, narrower turtles, while lower temperatures can result in larger, wider ones.

Nesting seasons vary by location. For example, in Parismina, Costa Rica, it's from February to July. In French Guiana, it's from March to August.

Why Leatherbacks are Important to Humans

People around the world still collect sea turtle eggs. This has been a major reason for the decline in leatherback populations globally. In some places, like Southeast Asia, collecting eggs has almost wiped out local nesting groups.

Leatherbacks are also very important because they are major predators of jellyfish. By controlling jellyfish populations, they help protect young fish. These fish grow up to be important for commercial fishing, which humans rely on.

Cultural Significance

The leatherback sea turtle is important to many cultures. The Seri people in Mexico see the leatherback as one of their five main creators. They hold ceremonies and fiestas when a turtle is caught before releasing it back into the wild. Because they've seen turtle populations drop, the Seri people created a conservation group called Grupo Tortuguero Comaac. This group uses both traditional knowledge and modern science to protect the turtles and their homes.

In the Malaysian state of Terengganu, the leatherback turtle is the state's main animal and is often featured in tourism ads.

On New Zealand's Banks Peninsula, the leatherback turtle holds great spiritual meaning for the Koukourārata hapū (a sub-tribe) of te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu, and for the wider Māori and Polynesian peoples.

Protecting Leatherback Turtles

Once leatherback turtles grow up, they have few natural predators. They are most vulnerable when they are eggs or hatchlings. Birds, small mammals, and other animals dig up nests and eat the eggs. Shorebirds and crustaceans prey on the hatchlings as they try to reach the sea. In the water, young leatherbacks can be eaten by predatory fish and cephalopods.

Leatherbacks face some unique threats from humans. Their meat is too oily and fatty to be popular, so they are not often hunted for food. However, human activities still harm them. Sometimes, they are accidentally caught in fishing nets, which is called bycatch. As the largest sea turtles, they can be too big for special devices meant to help turtles escape nets. Pollution is another big problem. Many turtles die from eating balloons and plastic bags, which look like jellyfish.

Light pollution from streetlights and buildings is also a serious threat to hatchlings. Baby turtles are naturally drawn to the brightest part of the horizon, which should be the ocean. Artificial lights can confuse them, making them crawl away from the sea and towards danger.

Global Efforts to Help

The leatherback sea turtle is listed on CITES Appendix I, which means it's illegal to export or import this species or its parts. It's also listed as "Vulnerable" on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Some groups of leatherbacks are even more endangered:

- East Pacific Ocean group: Critically Endangered

- Northwest Atlantic Ocean group: Endangered

- Southwest Atlantic Ocean group: Critically Endangered

- West Pacific Ocean group: Critically Endangered

National and Local Efforts

Many countries have laws and programs to protect leatherback sea turtles. The United States listed them as an endangered species in 1970. In 2012, a large area of the Pacific Ocean off California, Oregon, and Washington was set aside as "critical habitat" for them. In Canada, it's illegal to harm the species in Canadian waters.

Organizations like the Earthwatch Institute and Nature Seekers work with volunteers in places like Matura Beach, Trinidad, to protect nesting females and their eggs. This beach is one of the most important nesting sites for leatherbacks.

Several Caribbean countries use ecotourism to raise awareness and protect leatherbacks. In Parismina, Costa Rica, a hatchery program helps protect eggs from poachers. In Dominica, patrollers protect nesting sites.

Mayumba National Park in Gabon, Central Africa, was created to protect Africa's most important nesting beach. Over 30,000 turtles nest there each year.

In Brazil, the projeto TAMAR (TAMAR project) helps protect nests and prevent turtles from being accidentally caught by fishing boats. In January 2010, a female leatherback laid eggs in Pontal do Paraná, which was unusual for that area. Biologists protected the nests, even though the eggs might not have been fertile.

Australia also has laws to protect leatherbacks, listing them as vulnerable or endangered depending on the region.

See also

In Spanish: Tortuga laúd para niños

In Spanish: Tortuga laúd para niños

- Threats to sea turtles

- Pandermochelys

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |