Mount Tambora facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mount Tambora |

|

|---|---|

| Tomboro | |

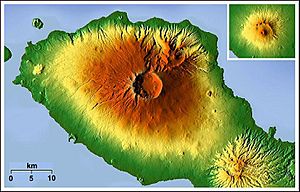

Caldera of Mount Tambora

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,850 m (9,350 ft) |

| Prominence | 2,722 m (8,930 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Bima & Dompu Regencies, Sanggar peninsula, Sumbawa, Lesser Sunda Islands, Indonesia |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Late Pleistocene-recent |

| Mountain type | Trachybasaltic-trachyandesitic stratovolcano |

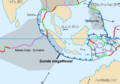

| Volcanic arc | Sunda Arc |

| Last eruption | 1967 |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Southeast: Doro Mboha Northwest: Pancasila |

Mount Tambora, also called Tomboro, is an active stratovolcano in Indonesia. It is found on Sumbawa island, which is part of the Lesser Sunda Islands. This volcano was formed because of active subduction zones deep below it. Before its huge eruption in 1815, Mount Tambora was one of the tallest mountains in Indonesia. It stood more than 4,300 meters (14,100 feet) high.

Mount Tambora erupted violently starting on April 5, 1815. This massive eruption caused big changes in the world's climate for several years. The year 1816 became known as the "year without a summer" in many parts of the world. This was because the eruption affected weather in North America and Europe. In the Northern Hemisphere, crops failed and farm animals died. This led to the worst famine of that century.

Mount Tambora is still an active volcano. Its last eruption was in 1967, but it was a gentle one and not explosive. A very small eruption was also reported in 2011.

Contents

Where is Mount Tambora Located?

Mount Tambora is located in the northern part of Sumbawa island. This island is part of the Lesser Sunda Islands. Tambora is also part of the Sunda Arc. This is a chain of volcanic islands that form the southern part of the Indonesian archipelago.

Mount Tambora creates its own peninsula on Sumbawa, called the Sanggar peninsula. To the north of this peninsula is the Flores Sea. To the south is the 86-kilometer (53-mile) long and 36-kilometer (22-mile) wide Saleh Bay. There is also a small island called Mojo at the mouth of Saleh Bay.

The Great Eruption of 1815

Before 1815, Mount Tambora had been a sleeping volcano for many centuries. In 1812, the volcano's crater started to rumble. It also created a dark cloud.

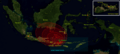

A medium-sized eruption happened on April 5, 1815. After this, very loud sounds like thunder could be heard far away. These sounds reached Ternate in the Molucca Islands, which is 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) from Mount Tambora. On the morning of April 6, 1815, volcanic ash began to fall in East Java. Faint rumbling sounds continued until April 10.

People on Sumatra island, more than 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) away, heard what they thought were gunshots on April 10 and 11. These sounds might have even been heard 3,350 kilometers (2,060 miles) away in Thailand and Laos.

The eruptions became much stronger around 7:00 p.m. on April 10. Three plumes of ash and gas rose and joined together. Pieces of pumice, which is a light, airy volcanic rock, up to 20 centimeters (8 inches) wide rained down around 8 p.m. Then, ash started falling around 9–10 p.m. The huge eruption column collapsed. This created hot pyroclastic flows. These are fast-moving currents of hot gas and volcanic debris. They rushed down the mountain towards the sea on all sides of the peninsula. The village of Tambora was completely destroyed.

Loud explosions continued until the next evening, April 11. A veil of ash spread as far as West Java and South Sulawesi. People in Batavia could smell a "nitrous odor." The heavy rain mixed with tephra (rock fragments and ash) did not stop until April 17.

Scientists believe this eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 7. This means it was incredibly powerful. It had 4 to 10 times more energy than the 1883 Krakatoa eruption. The explosion was heard 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) or even 3,350 kilometers (2,060 miles) away. Ash deposits were found at least 1,300 kilometers (810 miles) away. Complete darkness was seen up to 600 kilometers (370 miles) from the volcano's top for two days.

The Lost Village of Tambora

In 2004, a human settlement that was buried by the Tambora eruption was found. That summer, a team of scientists started an archaeological dig in Tambora. The team was led by Haraldur Sigurðsson. They worked for six weeks and found signs of people living about 25 kilometers (16 miles) west of the volcano's caldera. This area was deep in the jungle, about 5 kilometers (3 miles) from the coast.

The team dug through 3 meters (10 feet) of pumice and ash. They used ground-penetrating radar to find a small buried house. Inside, they found the remains of two adults, along with bronze bowls, ceramic pots, iron tools, and other items. Tests showed that these objects had been burned by the heat from the magma. Sigurdsson called this discovery the "Pompeii of the East." News reports called it the "Lost Kingdom of Tambora."

Based on the items found, like bronzeware and fancy china from Vietnam or Cambodia, the team thinks these people were wealthy traders. The people of Sumbawa were known in the East Indies for their horses, honey, sappan wood (used for red dye), and sandalwood (used for incense and medicines). The area was likely very good for farming.

What Happened After the Eruption?

The eruption destroyed all the plants on the island. Uprooted trees mixed with pumice ash washed into the sea. They formed huge floating rafts up to 5 kilometers (3 miles) wide. Thick clouds of ash still covered the volcano's top on April 23. The explosions stopped on July 15, but smoke was still seen as late as August 23. People reported flames and rumbling aftershocks in August 1819, four years after the main event.

A medium-sized tsunami hit the coasts of several Indonesian islands on April 10. Waves reached 4 meters (13 feet) high in Sanggar around 10 p.m. A tsunami with waves 1 to 2 meters (3 to 7 feet) high was reported in Besuki, East Java, before midnight. Another tsunami over 2 meters (7 feet) high was reported in the Molucca Islands.

The eruption column reached the stratosphere, more than 43 kilometers (141,000 feet) high. Larger ash particles fell one to two weeks after the eruptions. Finer particles stayed in the atmosphere for months to years. They floated at an altitude of 10 to 30 kilometers (6 to 19 miles). These fine particles spread around the world because of strong winds. This created beautiful optical effects. Between June 28 and July 2, and again between September 3 and October 7, 1815, people in London, England, often saw long, brightly colored sunsets and twilights. Usually, pink or purple colors appeared above the horizon at twilight, and orange or red colors were seen near the horizon.

How Many People Died?

Many sources have tried to guess how many people died from the Tambora eruption since the 1800s.

| Volcano | Location | Year | Column height (km) |

VEI | N. hemisphere summer change (°C) |

Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taupō Volcano | 181 | 51 | 7 | ? | unlikely | |

| Paektu Mountain | 946 | 25 | 7 | ? | ? | |

| Mount Samalas | 1257 | 38–43 | 7 | −1.2 | ? | |

| 1452/1453 mystery eruption | Unknown | 1452 | ? | 7 | −0.5 | ? |

| Huaynaputina | 1600 | 46 | 6 | −0.8 | ≈1,400 | |

| Mount Tambora | 1815 | 44 | 7 | −0.5 | >71,000 | |

| Krakatoa | 1883 | 80 | 6 | −0.3 | 36,600 | |

| Santa María Volcano | 1902 | 34 | 6 | no anomaly | 7,000–13,000 | |

| Novarupta | 1912 | 32 | 6 | −0.4 | 2 | |

| Mount St. Helens | 1980 | 24 | 5 | no anomaly | 57 | |

| El Chichón | 1982 | 32 | 5 | ? | >2,000 | |

| Nevado del Ruiz | 1985 | 27 | 3 | no anomaly | 23,000 | |

| Mount Pinatubo | 1991 | 34 | 6 | −0.5 | 1,202 | |

| Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai | 2022 | 58 | 5–6 | ? | 6 | |

| Sources: Oppenheimer (2003), and Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program | ||||||

Cool Facts About Mount Tambora

- The 1815 eruption of Tambora is the largest volcanic eruption ever recorded in human history.

- It released a huge amount of sulphur into the stratosphere, between 10 and 120 million tons.

- This eruption caused a worldwide climate change event. It is known as the "volcanic winter".

- The unique language of the Tambora people was lost forever because of the eruption.

Panorama

Images for kids

-

View of Mount Rinjani from Mount Tambora. Viewing distance is 165 kilometres (103 mi).

-

Sulfate concentration in ice core from Central Greenland, dated by counting oxygen isotope seasonal variations. There is an unknown eruption around the 1810s.

See also

In Spanish: Tambora para niños

In Spanish: Tambora para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |