Huaynaputina facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Huaynaputina |

|

|---|---|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | ≈4,850 m (15,910 ft) |

| Listing | List of volcanoes in Peru |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Lua error in Module:ISO_639_name at line 108: attempt to index local 'data' (a nil value). |

| Geography | |

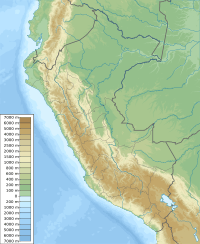

| Location | Peru |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

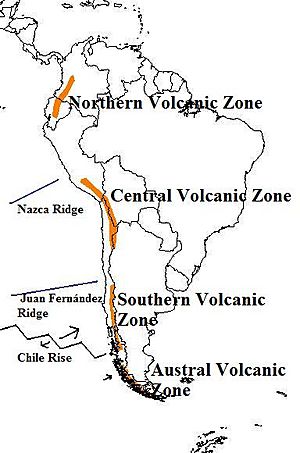

| Volcanic arc/belt | Central Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | February to March 1600 |

Huaynaputina (/ˌwaɪnəpʊˈtiːnə/ wy-NƏ-puu-TEE-nə) is a volcano located on a high plateau in southern Peru. It is part of the Central Volcanic Zone of the Andes mountains. This volcano was formed when the Nazca Plate (an oceanic plate) slid under the South American Plate (a continental plate).

Unlike many volcanoes, Huaynaputina doesn't look like a tall mountain. It's a large volcanic crater with three younger vents inside a bowl-shaped area. This area might be an old caldera or shaped by glacial ice. The volcano has erupted a type of magma called dacite.

Huaynaputina has erupted several times in the past. The biggest eruption happened on February 19, 1600. It was the largest eruption ever recorded in South America. This powerful event continued into March. People in the city of Arequipa witnessed it.

The eruption killed at least 1,000 to 1,500 people. It destroyed plants and covered the land with about 2 meters (6.6 feet) of volcanic rock. The eruption also damaged buildings and farming. It had a huge impact on Earth's climate, causing a "volcanic winter". Temperatures dropped in the Northern Hemisphere. Cold waves hit parts of Europe, Asia, and the Americas. This climate change might have even helped start the Little Ice Age. Floods and food shortages followed, possibly linked to problems in Russia. Scientists measure this eruption as a 6 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI).

The volcano has not erupted since 1600. There are still fumaroles (gas vents) in the bowl-shaped area. Also, hot springs are found nearby, some connected to Huaynaputina. The volcano is in a remote area with few people. However, about 30,000 people live close by. Another one million live in the Arequipa metropolitan area. If an eruption like the 1600 one happened again, it could cause many deaths and big problems. In 2017, Peru's Geophysical Institute announced that Huaynaputina would be watched by the Southern Volcanological Observatory. Seismic (earthquake) monitoring began in 2019.

Contents

- What's in a Name? Huaynaputina's Meaning

- Where is Huaynaputina Located?

- How Huaynaputina Formed: The Geology Story

- Huaynaputina's Eruption History

- The Great Eruption of 1600

- What are the Risks Today?

- Climate and Plants Around Huaynaputina

- See also

What's in a Name? Huaynaputina's Meaning

The volcano was named Huaynaputina after its big eruption in 1600. Some say "Huayna" means 'new' and "Putina" means 'fire-throwing mountain'. So, the full name suggests its powerful volcanic activity. It also refers to the 1600 eruption being its first known big one.

Other names for the volcano include Chequepuquina, Chiquimote, Guayta, Omate, and Quinistaquillas. Sometimes, the volcano El Misti was mistakenly called Huaynaputina.

Where is Huaynaputina Located?

Huaynaputina is part of the Central Volcanic Zone in the Andes mountains. Other volcanoes in this area include Sara Sara, Coropuna, Ampato, Sabancaya, El Misti, Ubinas, Ticsani, Tutupaca, and Yucamane. Ubinas is the most active volcano in Peru. Several of these volcanoes, including Huaynaputina, have been active in recent history.

Most volcanoes in this zone are large composite volcanoes. They can stay active for millions of years. Big explosive eruptions (VEI 6 or higher) happen here every 2,000 to 4,000 years on average.

Huaynaputina is in the Omate and Quinistaquillas Districts. These are in the Moquegua Region of southern Peru. The town of Omate is about 16 kilometers (10 miles) southwest of the volcano. The city of Moquegua is 65 kilometers (40 miles) south-southwest. Arequipa is 80 kilometers (50 miles) to the north-northwest.

This region is mostly remote and rugged. It's not easy to get to the area around Huaynaputina. There are few people living there. Small farms exist within 16 kilometers (10 miles) of the volcano. A path for cattle leads from Quinistaquillas to the volcano. The landscapes around the volcano are unique and important for geology.

What Does Huaynaputina Look Like?

Huaynaputina is about 4,850 meters (15,910 feet) high. It has an older, outer volcano. Inside it, there's a bowl-shaped area that is 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) wide and 400 meters (1,300 feet) deep. This bowl opens to the east. It sits within the older volcano at 4,400 meters (14,400 feet) elevation.

The volcano itself is not very tall. It rises less than 600 meters (2,000 feet) above the land around it. However, the ash and rocks from the 1600 eruption cover a large area. These deposits include sand-like dunes formed by hot ash flows.

Inside the bowl-shaped area are three younger volcanic vents. One is a 70-meter (230-foot) deep trench. A second vent was about 400 meters (1,300 feet) wide. The third vent is 80 meters (260 feet) deep and has a 200-meter (660-foot) wide pit. These vents are among the highest places where a Plinian eruption has happened.

Surroundings of Huaynaputina

West of the volcano, the land is a high plateau about 4,600 meters (15,100 feet) high. North of Huaynaputina are the Ubinas volcano and Laguna Salinas. South of it are the peaks Cerro El Volcán and Cerro Chen.

To the northeast and east, the land drops steeply into the Río Tambo valley. This river flows around Huaynaputina. Several smaller valleys join the Río Tambo from the volcano. The Río Tambo eventually flows into the Pacific Ocean.

How Huaynaputina Formed: The Geology Story

The Nazca Plate is slowly sliding under the South American Plate at about 10.3 centimeters (4 inches) per year. This movement causes volcanoes to form and the Andes mountains to rise. Volcanic activity in the Andes happens in specific areas called volcanic belts. Huaynaputina is in the Central Volcanic Zone.

Peru has about 400 volcanoes that formed in the last few million years. Active volcanoes are only in the southern part of the country. Many Peruvian volcanoes are not well studied because they are hard to reach.

The rocks under Huaynaputina are very old. They include thick layers of sediments and volcanic rocks. These older rocks were covered by even more volcanic deposits over time.

Local Volcanic Connections

The vents of Huaynaputina line up with nearby volcanoes like Ubinas and Ticsani. Ubinas is a typical cone-shaped volcano, while Ticsani is similar to Huaynaputina. These volcanoes are part of a larger volcanic area. They are connected by deep cracks in the Earth's crust. These cracks act like pathways for magma (molten rock) to rise to the surface.

The rocks from these volcanoes are similar. Past earthquake and volcanic activity suggest they might share a large magma chamber underground. This chamber could be about 40 by 60 kilometers (25 by 37 miles) in size.

What is Huaynaputina Made Of?

The rocks from the 1600 eruption are mostly dacite. These rocks are rich in potassium. They also contain smaller pieces of rhyolite. Some andesite has also been found at Huaynaputina.

These rocks contain different types of crystals, like biotite, hornblende, and plagioclase. The 1600 eruption also brought up pieces of older rocks from under the volcano. These older rocks had been changed by hot water. The pumice (lightweight volcanic rock) from Huaynaputina is white.

The magma's gas content changed during the 1600 eruption. This suggests the magma came from two different magma chambers or one chamber with different layers. This might explain why the eruption changed over time. The first rocks erupted were gassier and caused a huge explosion. Later rocks were thicker and caused smaller explosions.

The rocks were very hot, about 780 to 815 degrees Celsius (1,436 to 1,499 degrees Fahrenheit). The eruption might have been triggered when new, hot magma entered the existing magma system. This often causes explosive eruptions. Some magma came from very deep underground, while other magma came from shallower depths.

Huaynaputina's Eruption History

The older volcano that holds Huaynaputina formed millions of years ago. It was shaped by landslides and glaciers. The bowl-shaped area where Huaynaputina's vents are located probably formed from glacial ice or a landslide, not a caldera. Other old volcanoes nearby have similar bowl shapes.

Some dacite rocks formed recently in the Huaynaputina area, possibly just before the 1600 eruption.

Past Eruptions in Recent Times

Evidence of past eruptions can be found in the bowl-shaped area. Some ash layers near Ubinas volcano, dating back 7,000 to 1,000 years, are from Huaynaputina. Three eruptions have been dated to about 9,700, 7,480, and 5,750 years ago. These eruptions produced pumice and hot ash flows.

Before the 1600 eruption, people didn't know Huaynaputina was a volcano. There were no known eruptions, only some gas vents. The land before 1600 was described as a "low ridge." It's possible that small lava domes were at the top before the 1600 eruption, which were then blown away.

The last eruption before 1600 might have been centuries earlier. Native people reportedly offered sacrifices to the mountain. Since 1600, there have been no eruptions. A report of an eruption in 1667 is likely wrong and probably refers to Ubinas volcano instead.

Steaming Vents and Hot Springs

Fumaroles (gas vents) are found in the bowl-shaped area near the three vents. They produce white fumes and smell like rotten eggs. These gases are mostly water vapor, with some carbon dioxide and sulfur gases. In 2010, the gas temperatures ranged from 51.8 to 78.7 degrees Celsius (125.2 to 173.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

Hot springs are also found in the region. Some are linked to Huaynaputina. These springs have temperatures from 22.8 to 75.4 degrees Celsius (73.0 to 167.7 degrees Fahrenheit). They contain a lot of dissolved salts. Some springs seem to be fed by water from deep inside the Earth.

The Great Eruption of 1600

| 1600 eruption of Huaynaputina | |

|---|---|

| Type | Plinian, Vulcanian |

| VEI | 6 |

Huaynaputina's eruption began on February 19, 1600. Earthquakes had started four days earlier. The eruption may have lasted 12 to 19 hours. Earthquakes and ash fall continued for about two weeks, ending on March 6. The air was clear of ash by April 2, 1600.

At first, people thought the eruption was from Ubinas or El Misti. Priests in Arequipa recorded what they saw. The eruption's size and its climate impact have been studied using historical records, tree rings, and ice cores.

How the Eruption Unfolded

The eruption might have started when new magma entered the volcano's system. This built up pressure, causing magma to rise. As magma moved up, it caused earthquakes. People in Arequipa were so scared their houses would collapse. The rising magma hit an older hot water system underground. Parts of this system were blasted out during the eruption. Once the magma reached the surface, the eruption became very intense.

The first big stage happened on February 19 and 20. This was a Plinian eruption, which means it sent a huge column of ash and gas high into the sky. This stage lasted about 20 hours. It created pumice deposits 18 to 23 meters (59 to 75 feet) thick near the volcano. Ash from this stage reached as far as Antarctica. This first stage produced most of the material from the 1600 eruption. The eruption column was so high (34 to 46 kilometers or 21 to 29 miles) that it blocked out the sun and stars. After this, parts of the volcano's bowl-shaped area collapsed.

After a break, the volcano started erupting pyroclastic flows. These are fast-moving currents of hot gas and volcanic debris. They mostly flowed down valleys away from Huaynaputina, reaching up to 13 kilometers (8 miles) from the vents. Winds blew ash from these flows. Ash fall and pyroclastic flows happened one after another. During this time, a lava dome formed inside one of the vents.

Pyroclastic flows went down the volcano's slopes and into the Río Tambo valley. They blocked the river, forming lakes. When these natural dams broke, hot water with pumice and debris rushed down the river. These flows permanently changed the river's path. The pyroclastic flows covered an area of about 950 square kilometers (370 square miles).

In the third stage, Vulcanian eruptions (smaller, more explosive blasts) happened. They deposited another ash layer. The volcano also shot out lava bombs. This stage destroyed the lava dome and formed the third vent.

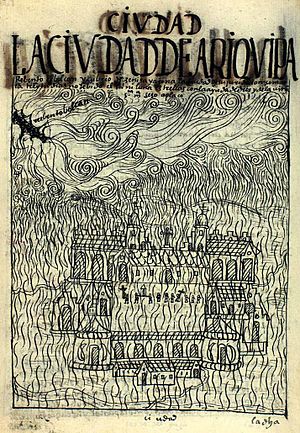

What People Saw and Heard

The eruption came with strong earthquakes and very loud explosions. These noises could be heard over 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) away, even in Lima. In Arequipa, the sky lit up with lightning, and ash fell so thickly that roofs collapsed. The noise sounded like artillery fire. The sky turned dark in Arequipa and Copacabana.

Closer to the volcano, people in the village of Puquina saw huge flames rising from Huaynaputina. Then, they were covered by falling pumice and ash.

No Big Collapse: Why No Caldera?

People first thought a caldera (a large basin formed when a volcano collapses) formed during the 1600 eruption. This is because accounts said the volcano was "obliterated." However, later studies showed this wasn't the case. Very large eruptions usually form calderas, but Huaynaputina was an exception. This might be because most of the magma came from very deep underground (20 kilometers or 12 miles).

Some smaller collapse structures did form inside the bowl-shaped area. These happened as the magma system lost pressure during the eruption. Part of the northern side of the bowl also collapsed.

How Big Was the Eruption?

The 1600 eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 6. It is the only major explosive eruption in the Andes in recorded history. It was the largest volcanic eruption in all of South America in historical times. It was even bigger than the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa and the 1991 eruption of Pinatubo. Huaynaputina's eruption column was so high it reached the upper atmosphere. This allowed it to affect Earth's climate.

The total amount of volcanic rock erupted was about 30 cubic kilometers (7.2 cubic miles). Most of this came from the first stage of the eruption.

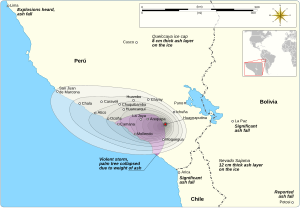

Ash and Rock Fallout

Ash from Huaynaputina was at least 1 centimeter (0.4 inches) thick over an area of 95,000 square kilometers (37,000 square miles). This covered parts of southern Peru, Bolivia, and Chile. Closer to the volcano, the ash was over 1 meter (3.3 feet) thick. The ash fell mostly to the west, which is unusual for volcanoes in this region. The ash deposits are still visible today. Several ancient sites are preserved under them.

Ash layers from Huaynaputina have been found in ice cores in Quelccaya (Peru) and Sajama (Bolivia). The ash layer has been used by scientists to date other events. It has also been found in ice cores in Greenland and Antarctica. Some even suggest it marks the start of the Anthropocene (a new geological age shaped by humans).

Local Impact of the Eruption

The eruption had a terrible impact on the region. Ash and pumice buried the land under more than 2 meters (6.6 feet) of rock. Pyroclastic flows burned everything in their path. This destroyed plants over a large area. Ash and pumice falls were the most damaging. These, along with debris and pyroclastic flows, devastated an area of about 40 by 70 kilometers (25 by 43 miles). Both crops and farm animals were severely harmed.

Between 11 and 17 villages near the volcano were buried by ash. Some villages reportedly lost all their people. One priest visiting Omate after the eruption said he found people "dead and cooked with the fire of the burning stones." Estagagache has been called the "Pompeii of Peru."

In Arequipa, up to 1 meter (3.3 feet) of ash fell. This caused roofs to collapse. Ash fall was reported over a huge area of 300,000 square kilometers (120,000 square miles). This included cities like La Paz, Cuzco, and Potosi. Ships observed ash fall as far as 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) west of the coast.

People who survived fled during the eruption. Wild animals sought safety in Arequipa. The eruption, along with earthquakes and floods, caused some farmed land to be abandoned.

The eruption killed 1,000 to 1,500 people. This doesn't include deaths from earthquakes or floods. Flooding happened when volcanic dams in the Río Tambo broke. Mudslides reached the Pacific Ocean, 120 to 130 kilometers (75 to 81 miles) away.

The damage to buildings and the economy in southern Peru was severe. The local wine industry was wiped out. After the eruption, the focus of wine making shifted to other areas. Sugarcane later became important in the Moquegua valley. Cattle farming was also badly affected.

The Arequipa and Moquegua areas lost many people due to sickness and food shortages. Recovery only began much later. Indigenous people moved from ash-covered valleys to Moquegua. Taxes were stopped for years. Workers were brought from far away to help rebuild. Arequipa went from being a rich city to a place of hunger and disease.

Religious Reactions to the Eruption

People in Arequipa held religious parades and prayers to calm what they thought was divine anger. Some who had lost faith in the church turned to magic. In Moquegua, children ran around screaming, and women cried.

The Spaniards saw the eruption as a punishment from God. Native people thought it was a god fighting against the Spanish. One myth says that Omate volcano (Huaynaputina) asked Arequipa volcano (probably El Misti) to help destroy the Spanish. But El Misti refused, saying it was Christian now. So Huaynaputina exploded in anger alone.

El Misti had erupted less than two centuries before. People were worried it might erupt next. So, native people and priests threw sacrifices into its crater. In Arequipa, a new patron saint was named after the eruption.

Some prophecies before the eruption suggested a disaster was coming. There are reports that a sacrifice was happening at the volcano a few days before the eruption.

Global Climate Effects of the 1600 Eruption

After the eruption, people in Europe and China saw the sun look "dim" or "reddish." It was like a haze that reduced the sun's brightness. Bright sunsets and sunrises were also noticed. A dark lunar eclipse in Austria in 1601 might have been caused by Huaynaputina's ash in the atmosphere.

Scientists found acid layers in ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland. These layers are linked to Huaynaputina. This discovery led to discussions about how much the 1600 eruption affected Earth's climate. The eruption released a huge amount of sulfuric acid into the atmosphere.

Volcanic eruptions change the world's climate by sending ash and gases high up. This reduces sunlight, often causing cold weather and crop failures. The Huaynaputina eruption reduced the sun's energy reaching Earth. The summer of 1601 was one of the coldest in the Northern Hemisphere in 600 years. The impact was similar to other huge eruptions like Tambora in 1815. The eruption is believed to have caused a volcanic winter.

The eruption had a clear impact on plant growth in the Northern Hemisphere. Summers were about 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) colder than average. This climate impact has been seen in tree rings from places like Taiwan, Siberia, Canada, and California.

Long-Term Climate Changes

Temperatures stayed low for a long time after the Huaynaputina eruption in the Northern Hemisphere. This eruption, along with others, may have helped cause the Little Ice Age. This was a period of colder temperatures in Europe. Glaciers grew, and Arctic sea ice expanded after these eruptions. Volcanic sulfur in the atmosphere was higher during the Little Ice Age.

The 1600 eruption happened at the end of several medium-sized eruptions. Climate simulations show this had a big impact on Earth's energy balance. It caused a 10% growth of sea ice in the Northern Hemisphere.

Impacts Far Away from Peru

North America's Experience

Thin tree rings and frost rings linked to the Huaynaputina eruption have been found in trees in the Northeastern and Western United States. Tree rings from Quebec show cold temperatures in 1601 and 1603. In 1601, Alaska recorded its coldest temperature in 600 years.

The eruption was followed by a drought in the Eastern U.S.. This may have made it harder to establish the Jamestown colony. Many people died from lack of food there. The eruption might also have contributed to the disappearance of the Monongahela culture.

California's Floods

A major flood in California around 1605 has been linked to the Huaynaputina eruption. Global cooling from the eruption may have pushed storm paths south. This caused floods in the Southwestern United States. At that time, Mono Lake rose to its highest level in 1,000 years. Colder temperatures would have reduced evaporation, leading to more water.

Spanish explorers visited the US west coast after the eruption. The widespread flooding may have made them believe that California was an island. This became a famous map mistake in history.

Western Europe's Cold Snap

Tree rings show unusually cold weather in the Austrian Alps and Estonia. The winter of 1601–1602 was the coldest in half a millennium there. Summers in Quebec and Scandinavia after the eruption were the coldest in 420 years. Tree ring analysis suggests cooling in Greece, Finland, and Switzerland.

The winter of 1601 was extremely cold in Estonia, Ireland, and Latvia. The 1601 wine harvest in France was delayed. In Germany, it was much lower in 1602. Frost continued into summer in Italy and England. In Estonia, high death rates and crop failures from 1601 to 1603 caused many farms to be abandoned. Scotland saw crop failures and a plague outbreak.

In Sweden, harvest failures were recorded between 1601 and 1603. A rainy spring in 1601 led to food shortages. Finland had some of its worst harvests. The year 1601 was called a "green year" in Sweden and a "straw year" in Finland.

Russia's Famine and Troubles

Ice cores in the Russian Altai Mountains show strong cooling around 1601. Tree ring data also recorded a temperature drop.

The summer of 1601 was wet, and the winter of 1601–1602 was harsh. The eruption caused the Russian famine of 1601–1603. This was the worst famine in Russian history, killing about two million people. These events started a time of social unrest called the Time of Troubles. The tzar Boris Godunov was overthrown partly because of the famine.

China's Cold and Famine

Records from northern China mention severe frosts in 1601. They also note frequent cold weather, including summer snowfall. These frosts destroyed crops, leading to severe food shortages. Sickness outbreaks in Shanxi and Shaanxi have also been linked to Huaynaputina.

Weather was also unusual in southern China. 1601 saw a hot autumn and a cold summer. Snowfall and unusual cold were reported in the Yangtze River valley.

What are the Risks Today?

About 30,000 people live very close to Huaynaputina today. Over 69,000 live in Moquegua, and 1,000,000 in Arequipa. Towns like Calacoa, Omate, Puquina, and Quinistaquillas would be in danger if the volcano erupted again. If an eruption like the 1600 one happened, it would likely cause many more deaths now. This is because the population has grown so much. It would also cause big economic problems in the Andes.

The 1600 eruption is often used as a "worst-case scenario" for Peruvian volcanoes. Huaynaputina is considered a "high-risk volcano." In 2017, Peru's Geophysical Institute announced that Huaynaputina would be monitored. Seismic (earthquake) monitoring began in 2019. As of 2021, there are three seismometers and one device measuring volcano changes on Huaynaputina.

During the wet season, mudflows often come down from Huaynaputina. In 2010, earthquakes and noises from the volcano worried local people. This led to a scientific study. Researchers found earthquake activity around the volcano's bowl-shaped area. They recommended more monitoring of the area.

Climate and Plants Around Huaynaputina

At elevations between 4,000 and 5,000 meters (13,000 and 16,000 feet), average temperatures are about 6 degrees Celsius (43 degrees Fahrenheit). Nights are cold. At Omate, average temperatures reach 15 degrees Celsius (59 degrees Fahrenheit). There isn't much change between seasons.

The area gets about 154.8 millimeters (6.1 inches) of rain per year. Most of this falls during the summer wet season (December to March). This makes the climate very dry. Not much erosion happens, so volcanic deposits are well preserved.

Plants are scarce around Huaynaputina. Plants only grow on the pumice deposits from the 1600 eruption during the wet season. Cacti can be found on rocky areas and in valley bottoms.

See also

In Spanish: Huaynaputina para niños

In Spanish: Huaynaputina para niños

- Corral de Coquena

- Timeline of volcanism on Earth