Sami people facts for kids

The Sami people are an ethnic group living in Lapland. Lapland is a region in the far north of Europe. It is part of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Sami people live in all these countries. There are between 80,000 and 135,000 Sami people in the world.

There are 10 different spoken Sami languages. Six of these can be written.

Contents

Sami Life and Reindeer Herding

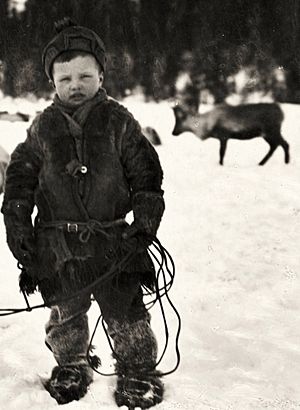

The Sami are well known for raising reindeer. In the past, many Sami were nomads. They moved with their reindeer herds. The Sami used reindeer for almost everything they needed. They ate meat, milk, and cheese. Their clothing and tents were made from reindeer skins. Wool clothes were often beautifully decorated.

The Sami protected their reindeer herds. They moved with the herds as they traveled from summer to winter pastures. Reindeer pulled sleds carrying supplies. In winter, the herds moved south of the tree line. The Sami lived nearby in homes made of logs or sod.

The Sami used every part of a dead reindeer. Milk was for drinking or making cheese. Meat was for food. Blood was frozen for soup and pancakes. Knives and belt buckles were carved from bones and antlers. Tendons were used as sewing thread. Cleaned stomachs carried milk or cheese.

Winter clothing had layers of reindeer skin. The inner layer had fur facing in. The outer layer had fur facing out. Boots were also made of fur. They were lined with grass gathered in summer. Each evening, the grass was dried by the fire. This kept the Sami warm in cold weather.

Today, fewer Sami people follow the herds. Those who do use modern tools. They use snowmobiles to herd reindeer. Rifles are used to protect herds from wolves. Even helicopters and radios help find and move reindeer. Most Sami now live on small farms. They raise crops and animals, including some reindeer. Selling reindeer meat is an important way for them to earn income.

Sami Culture

Norway, Sweden, and Finland now work to support Sami culture. They help build Sami cultural centers and promote Sami language.

Duodji (Handicraft)

Duodji is the traditional Sami handicraft. It comes from a time when Sami people were self-sufficient nomads. Objects were made to be useful, not just pretty. Men often used wood, bone, and antlers. They made things like antler-handled Sámi knives, drums, and guksi (wooden cups). Women used leather and roots. They made gákti (clothing) and woven baskets from birch and spruce roots.

Clothing

Gákti are the traditional clothes worn by the Sami people. They are worn for special events and for work, especially when herding reindeer.

In the past, gákti were made from reindeer leather. Today, wool, cotton, or silk are more common. Women's gákti usually include a dress and a fringed shawl. The shawl is held with silver brooches. Boots are made of reindeer fur or leather. Sami boots often have pointed or curled toes. They can have woven ankle wraps. Eastern Sami boots have a rounded toe and are lined with felt. They have beaded designs. Men's gákti are shorter, like a jacket-skirt. Women's dresses are long.

Traditional gákti are often red, blue, green, white, or brown leather. In winter, a reindeer fur coat and leggings are added. Sometimes a poncho (luhkka) and a rope/lasso are also worn.

The colors, patterns, and jewelry on a gákti show where a person is from. They can also show if someone is single or married. Sometimes they even show a person's family. The collar, sleeves, and hem often have geometric shapes. Some regions use ribbonwork or tin embroidery. Some Eastern Sami use beads on their clothes. Hats change by gender, season, and region. They can be wool, leather, or fur. Some are embroidered. Eastern hats are more like a beaded cloth crown with a shawl.

Gákti can be worn with a belt. These belts are sometimes woven or beaded. Leather belts can have carved antler buttons or silver decorations. Belts can also have beaded leather pouches, antler needle cases, and a carved knife.

Media and Literature

- Short daily news is shown in Northern Sámi on TV in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.

- Children's television shows are often made in Sami.

- There is a radio station for Northern Sámi. It has news in other Sami languages too.

- One daily newspaper, Ávvir, is published in Northern Sámi. There are also a few magazines.

- The Beaivváš Sámi Theatre is in Kautokeino, Norway. Another is in Kiruna, Sweden. They travel across the Sami area. They perform plays by Sami writers or translated international plays.

- Many novels and poetry books are published each year in Northern Sámi. Some are in other Sami languages. Davvi Girji is the largest Sami publishing house.

- The first non-religious book in a Sami language was Muitalus sámiid birra by Johan Turi. It came out in 1910. It was in Northern Sámi and Danish.

- In 2023, Sami author Ann-Helén Laestadius wrote "Stolen." It is a novel about the Sami in Sweden.

Music

A special part of Sami music is joik. Joiks are song-chants. They are traditionally sung a cappella (without instruments). They are often slow and deep, showing feelings like sadness or anger. Joiks can be about animals, people, or special events. They can be joyful, sad, or thoughtful. They often use improvised sounds. Today, musical instruments often go with joiks. The only traditional Sami instruments used with joik were the "fadno" flute and hand drums.

Education

- Education with Sami as the main language is available in all four countries. It is also available outside the Sami area.

- Sámi University College is in Kautokeino. Sami language is studied at several universities. The University of Tromsø sees Sami as a native language, not a foreign one.

Festivals

- Many Sami festivals celebrate different parts of Sami culture. Riddu Riđđu is well known in Norway. Others include Ijahis Idja in Inari.

- The Easter festivals in Kautokeino and Karasjok are very festive. They happen before the reindeer move to the coast in spring. These festivals mix traditional culture with modern things like snowmobile races. They celebrate the new year, called Ođđajagemánnu.

- Shamanic culture is celebrated at the Isogaisa Festival in Tennevoll, Norway.

Visual Arts

Besides Duodji (Sami handicraft), modern Sami visual art is growing. Galleries like Sámi Dáiddaguovddáš (Sami Center for Contemporary Art) are being created.

Dance

Unlike many other Indigenous peoples, traditional dance is not always a clear part of Sami identity. This has led to a common idea that Sami, at least in western Sápmi, have no traditional dance.

The Sami modern dance group Kompani Nomad looked at old writings about shamanistic rituals. They tried to find "lost" Sami dances and recreate them through modern dance. One example is the lihkadus. It was described in the 16th and 17th centuries. A Swedish-Sami priest, Lars Levi Laestadius, brought it into the Church of Sweden.

Partner and group dancing have been part of Skolt Sami culture. They have also been part of Sami culture on the Kola Peninsula since the late 1800s. These dances were influenced by Karelian and Northern Russian dance. This Eastern Sápmi dance tradition has continued. Modern Sami dance groups like Johtti Kompani have adapted it.

Reindeer Husbandry

Reindeer herding has always been important to Sami culture. In the past, Sami lived and worked in reindeer herding groups called siidat. These groups had several families and their herds. Members of the siida helped each other manage the herds. During times of forced assimilation, reindeer herding areas were some of the few places where Sami culture and language survived.

Today in Norway and Sweden, reindeer herding is legally protected. Only Sami people connected to a reindeer herding family can own and make a living from reindeer. About 2,800 people herd reindeer in Norway. In Finland, anyone living in the area can herd reindeer, not just Sami. In northern Lapland, it is a big part of the local economy.

Among Sami reindeer herders, women often have more formal education in this area.

Games

The Sami traditionally played card and board games. But few Sami games survived. This is because Christian missionaries thought such games were sinful. Only three Sami board games' rules are known today.

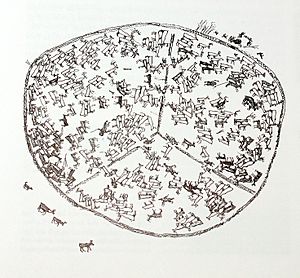

Sáhkku is a board game where players control "soldiers" (called "women" and "men"). They race around a board, trying to remove the other player's soldiers. It is similar to games like daldøs and tâb. Sáhkku is different because it has a "king" piece that changes the game a lot.

Tablut is a strategy game in the tafl family. It has "Swedes" and a "Swedish king" who tries to escape. An army of "Muscovites" tries to capture the king. Tablut is the only tafl game with rules that have survived well. So, all modern tafl games are based on the Sami game of tablut.

Dablot Prejjesne is like the game alquerque. It is different from most similar games (like draughts) because it has pieces of three different ranks. The two sides are called "Sámi" (king, prince, warriors) and "Finlenders" (landowners, landowner's son, farmers).

Important Sami Towns

Many towns and villages have a large Sami population or Sami institutions. Here are some of them:

- Aanaar, Anár, or Aanar (Inari): Home to the Finnish Sámi Parliament and the Inari Sámi Siida Museum.

- Aarborte (Hattfjelldal): A Southern Sami center with a language school.

- Árjepluovve (Arjeplog): The Pite Sami center in Sweden.

- Deatnu (Tana): Has many Sami people.

- Divtasvuodna (Tysfjord): A center for the Lule-Sami people. The Árran Lule-Sami center is here.

- Gáivuotna (Kåfjord, Troms): Important for Sea-Sami culture. The Riddu Riđđu festival is held here each summer.

- Giron (Kiruna): Proposed seat of the Swedish Sami Parliament.

- Guovdageaidnu (Kautokeino): Often called the cultural capital of the Sami. About 90% of people here speak Sami. It has the Beaivváš Sámi Theatre, Sámi University College, and the International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry. It also hosts the Sami Grand Prix music festival and Reindeer Racing World Cup.

- Jåhkåmåhkke (Jokkmokk): Holds a Sami market every February. It has a Sami school for language and traditional knowledge.

- Kárášjohka (Karasjok): Seat of the Norwegian Sámi Parliament. It has NRK Sámi Radio, the Sámi Collections museum, and the Sami Art Centre.

- Leavdnja (Lakselv) in Porsáŋgu (Porsanger): Location of the Finnmark Estate and the Ságat Sami newspaper.

- Луя̄ввьр (Lovozero): A center for Sami in Russia.

- Staare (Östersund): Center for the Southern Sámi people in Sweden. It has Gaaltije – a center for South Sami culture.

- Njauddâm: Center for the Skolt Sami of Norway. It has their museum, Äʹvv.

- Ohcejohka (Utsjoki).

- Snåase (Snåsa): A center for the Southern Sami language. It is the only place in Norway where Southern Sami is an official language. The Saemien Sijte Southern Sami museum is here.

- Unjárga (Nesseby): Important for Sea Sami culture. It has the Várjjat Sámi Museum.

- Árviesjávrrie (Arvidsjaur): Sami traditions are well preserved here. Sami people use this city for reindeer herding in summer.

Sami Population

The Sami are a small group in the Sápmi area. The total Sami population is estimated to be around 70,000 to 135,000. It is hard to count them exactly. There are many Sami languages and dialects. Also, many Sami do not speak their native language due to forced cultural assimilation. But they still see themselves as Sami. Other ways to identify as Sami include kinship, family origin in Sápmi, or protecting Sami culture.

All Nordic Sami Parliaments use self-identification as a main rule for registering as Sami. This means a person must truly feel they are Sami. Other rules are usually about family and language.

Roughly half of all Sami live in Norway. Many live in Sweden. Smaller groups live in northern Finland and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. The Sami in Russia were forced to move to a collective called Lovozero.

Sami Identity Symbols

Sami people have always seen themselves as one group. But the idea of Sápmi, a Sami nation, became popular in the 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s, a Sami flag was created. A Sami anthem was written. A national day was set.

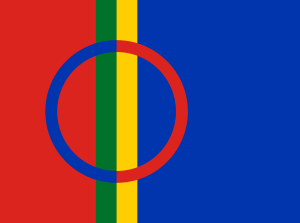

The Sami Flag

The Sami flag was first shown on August 15, 1986, in Åre, Sweden. Many designs were submitted. The winning design was by artist Astrid Båhl from Skibotn, Norway.

The flag's design comes from the shaman's drum. It also comes from the poem "Päiven Pārne" ("Sons of the Sun") by Anders Fjellner. This poem describes the Sami as sons and daughters of the sun. The flag has the Sami colors: red, green, yellow, and blue. The circle shows the sun (red) and the moon (blue).

The Sami People's Day

The Sami National Day is on February 6. This date marks the first Sami congress. It was held in 1917 in Trondheim, Norway. This was the first time Norwegian and Swedish Sami met to solve common problems. The decision to celebrate on February 6 was made in 1992. Since 1993, Norway, Sweden, and Finland have recognized February 6 as Sami National Day.

"Song of the Sami People"

"Sámi soga lávlla" ("Song of the Sami People") was first a poem by Isak Saba. It was published on April 1, 1906. In August 1986, it became the Sami anthem. Arne Sørli set the poem to music. This was approved in 1992. "Sámi soga lávlla" has been translated into all the Sámi languages.

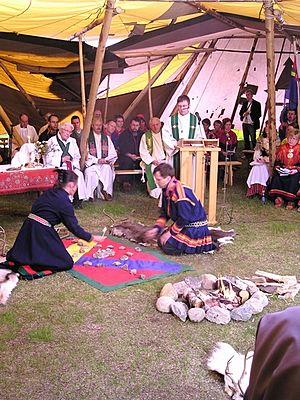

Religion and Spirituality

Sami shamanism was the main religion of the Sami people. These beliefs are connected to the land, animals, and the supernatural. Some Sami practiced bear worship. Sami shamanism is a polytheistic religion. It believes in many gods. Sami shamans are called 'Noadi'. There are also 'wise men' and 'wise women' who try to heal sick people. They use rituals and herbal medicine. Some Sami people have become Christian. They join either the Russian Orthodox Church or the Lutheran church.

Images for kids

-

A Sea Sámi man from Norway by Prince Roland Bonaparte in 1884

-

Suorvajaure near Piteå

-

Sámi people in Härjedalen (1790–1800), far south in the Sápmi area

-

Laponian area in Sápmi, UNESCO World Heritage Site

-

Sámi traditional presentation in Lovozero, Kola Peninsula, Russia

-

Reindeer in Alaska

-

Land rights for grazing reindeer

-

Copper etching (1767) by O.H. von Lode showing a noaidi with his meavrresgárri drum

-

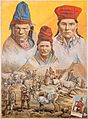

Ad for an 1893/1894 ethnological exposition of Sámi in Hamburg-Saint Paul

-

Anja Pärson a Sámi skier from Sweden

-

Börje Salming, a retired ice hockey defenceman

See also

In Spanish: Samis para niños

In Spanish: Samis para niños