Scottish clan facts for kids

A Scottish clan is like a big family group among the Scottish people. The word 'clan' comes from a Gaelic word meaning 'children' or 'family'. Clans give people a feeling of shared history and belonging. Today, clans have an official structure recognized by the Court of the Lord Lyon, which deals with Scottish heraldry and coats of arms. Most clans have their own special tartan patterns. These patterns usually started in the 1800s. Clan members can wear their tartan on kilts or other clothes.

The modern idea of clans, each with its own tartan and specific land, became popular thanks to Scottish author Sir Walter Scott. Historically, tartan designs were linked to areas where weavers made popular patterns. Over time, families in a certain area started wearing that area's tartan. Soon, the community became known by its tartan.

Many clans have their own clan chief. Clans without a recognized chief are called armigerous clans. Clans usually identify with areas their founders once controlled. They often have an ancestral castle and hold clan gatherings. These gatherings are a regular social event. A famous recent event was The Gathering 2009 in Edinburgh. It brought together at least 47,000 people from all over the world.

It's a common idea that everyone with a clan's name is a direct descendant of the chiefs. But this is not true. Many clan members were not related to the chief by blood. They took the chief's last name to show loyalty or to get protection and food. Most followers of a clan were tenants who worked for the clan leaders. By the 1700s, the idea grew that the whole clan came from one ancestor. This might have come from the Gaelic word clann meaning 'children'.

Understanding Scottish Clans

What is a Clan?

The word clan comes from the Gaelic word clann, meaning 'children' or 'family'. A clan was a community that accepted the authority of a strong group in their area. Clans also included many loosely related families called septs. All these families looked to the clan chief as their leader and protector.

According to a former Lord Lyon, Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, a clan is a group known by its special heraldry. It is officially recognized by the King or Queen. The Lord Lyon grants or recognizes the coats of arms of a clan chief. This gives royal recognition to the whole clan. So, clans with recognized chiefs are considered a noble community under Scots law.

A group without a chief recognized by the Lord Lyon has no official standing. A chief is the only person allowed to use the original undifferenced arms of the clan's founder. The clan is seen as the chief's inherited property. The chief's Seal of Arms is the official seal of the clan. Under Scots law, the chief is the head of the clan. They are the legal representative of the clan community.

Historically, a clan included everyone living on the chief's land. Over time, clan boundaries changed. Clans ended up with many unrelated members who had different last names. Often, people living on a chief's land would adopt the clan surname. A chief could also add families to their clan. They also had the right to outlaw anyone from their clan. Today, anyone with the chief's surname is automatically a clan member. Also, anyone who promises loyalty to a chief becomes a member.

How Clan Membership Works

Clan membership usually goes through the father's surname. Children who take their father's surname are part of their father's clan. They are not part of their mother's clan. However, some people have changed their surname to claim a chiefship through their mother's family. For example, the late chief of the Clan MacLeod changed his name to his maternal grandmother's maiden name.

Today, clans may have lists of septs. Septs are surnames or families that are linked to a clan. There is no official list of clan septs. Each clan decides which septs it has. Sometimes, sept names are shared by more than one clan. Individuals might need to use their family history to find their correct clan.

Clan Leadership and Land

Scottish clanship had two main ideas about heritage. First was the collective heritage of the clan, called their dùthchas. This was their right to live in the territories where the chiefs offered protection. All clan members recognized the chiefs' authority as guardians for their clan.

The second idea was the wider acceptance of charters given by the Crown to the chiefs. These charters defined the land settled by their clan. This was called their oighreachd. It gave the chiefs authority as landowners, not just as guardians. From the start, the clan warrior elite, called the ‘fine’, wanted to own land and be war lords.

Social Connections

Fosterage and manrent were very important for social bonding in clans. In fosterage, the chief's children would be raised by a favored clan family. In return, their children would be favored by clan members.

Manrent was a promise made by family heads to the chief for protection. These families did not live on the clan elite's land. These promises were strengthened by calps. These were death duties paid to the chief as a sign of loyalty when a family head died. It was usually their best cow or horse. Even though calps were banned in 1617, manrent continued secretly for protection.

Marriage alliances also strengthened ties with neighboring clans. They also reinforced links with families within the clan's territory. Marriage was also a business deal. It involved exchanging livestock, money, and land. The bride's payment was called the tocher, and the groom's was the dowry.

Managing the Clan Lands

Rents from people living on clan land were collected by tacksmen. These lesser gentry acted as estate managers. They assigned runrig strips of land. They also lent seed-corn and tools. They arranged for cattle to be driven to the Lowlands for sale. They took a small share of the payments made to the clan nobility, the fine.

Tacksmen also had an important military role. They mobilized the Clan Host. This was needed for warfare. More commonly, it was a large gathering of followers for weddings and funerals. Traditionally, in August, they organized hunts. These hunts included sports for the followers, which were the early versions of modern Highland games.

Clan Conflicts

When the oighreachd (land owned by the clan elite) did not match the dùthchas (the collective territory of the clan), it led to land disputes and warfare. The fine did not like their clan members paying rent to other landlords. Some clans used disputes to expand their territories. The Clan Campbell and the Clan Mackenzie were known for using disputes to gain land and influence.

Feuding was very intense on the western coast. The Clan MacLeod and the Clan MacDonald on the Isle of Skye were said to be eating dogs and cats in the 1590s because of it. Scottish clans also got involved in wars between the Irish Gaels and the English in the 1500s. Within these clans, a group of warriors developed. They were purely fighters and moved to Ireland seasonally as mercenaries.

There was heavy feuding during the civil wars of the 1640s. However, by this time, chiefs preferred to settle local disputes using the law. After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, feuding between clans greatly decreased. The last "clan" feud that led to a battle outside of a civil war was the Battle of Mulroy on August 4, 1688.

Cattle raiding, called "reiving" or creach, was common before the 1600s. Young men would take livestock from neighboring clans. By the 1600s, this declined. Most reiving was then called sprèidh. Smaller groups of men raided the nearby Lowlands. The stolen livestock could usually be recovered by paying tascal (information money) and promising no prosecution. Some clans, like the Clan MacFarlane and the Clan Farquharson, offered Lowlanders protection from raids. This was similar to blackmail.

Lowland Clans

An act of the Scottish Parliament in 1597 mentioned "Chieftains and chiefs of all clans... dwelling in the Highlands or Borders." Some argue this phrase describes Borders families as clans. The act lists Lowland families like the Maxwells, Johnstones, Carruthers, and Turnbulls. These were famous Border Reivers' names.

Sir George MacKenzie of Rosehaugh, a legal expert in 1680, said: "By the term 'chief' we call the representative of the family... and in the Irish [Gaelic] with us the chief of the family is called the head of the clan." This means the words chief or head and clan or family can be used interchangeably. So, it is correct to say the MacDonald family or the Stirling clan. The idea that Highlanders were clans and Lowlanders were families was a 19th-century custom. Even though Gaelic has not been spoken in the Scottish Lowlands for nearly 600 years, it is fine to call Lowland families, like the Douglases, "clans."

The Lowland Clan MacDuff is specifically called a "clan" in Scottish Parliament law from 1384.

Clan History

Early Origins

Many clans often claimed mythical founders. This made their status stronger and gave a romantic idea of their beginnings. Most powerful clans claimed origins based on Irish mythology. For example, the Clan Donald claimed to be descended from Conn, a 2nd-century king of Ulster. Their rivals, the Clan Campbell, claimed Diarmaid the Boar as their ancestor.

In reality, clan founders can rarely be traced back further than the 11th century. A continuous family line is often not found until the 13th or 14th centuries.

Clans emerged more from political unrest than from ethnicity. When the Scottish Crown conquered Argyll and the Outer Hebrides from the Norsemen in the 1200s, it created chances for war lords. They took control over local families who accepted their protection. These warrior chiefs were mostly Celtic. However, their origins ranged from Gaelic to Norse-Gaelic and British. By the 1300s, more families arrived. Their backgrounds included Norman, Anglo-Norman, and Flemish. Examples include the Clan Cameron, Clan Fraser, Clan Menzies, Clan Chisholm, and Clan Grant.

During the Wars of Scottish Independence, Robert the Bruce introduced feudal land ownership. He used this to gain support against the English. For example, the Clan MacDonald gained power over the Clan MacDougall. Both clans came from a great Norse-Gaelic warlord named Somerled from the 1100s. So, clanship was not just about family ties. It was also about loyalty to the Scottish Crown. This feudal part, supported by Scots law, makes Scottish clanship different from tribalism.

Civil Wars and Jacobite Rebellions

During the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, everyone believed monarchy was chosen by God. The choice to support King Charles I or the Covenanter government was often based on disputes within the Scottish elite. In 1639, Argyll, head of Clan Campbell, was given special powers. He used them to take MacDonald lands in Lochaber and Ogilvy lands in Angus. Because of this, both clans supported Montrose's Royalist campaign in 1644–1645. They hoped to get their lands back.

When Charles II became king again in 1660, a law restored bishops to the Church of Scotland. Many chiefs supported this. It fit the clan's hierarchical structure and encouraged obedience. Both Charles and his brother James VII used Highland soldiers, called the "Highland Host." They used them to control Campbell-dominated areas and stop the 1685 Argyll's Rising. By 1680, fewer than 16,000 Catholics lived in Scotland. They were mostly aristocrats and Gaelic-speaking clans in the Highlands and Islands.

When James was removed from power in the 1688 Glorious Revolution, clans chose sides based on what benefited them. The Presbyterian Macleans supported the Jacobites to get back lands they lost to the Campbells. The Catholic Keppoch MacDonalds tried to attack the pro-Jacobite town of Inverness. They were stopped only after Dundee stepped in.

Highland involvement in the Jacobite risings was due to their remote location. Also, the feudal clan system required tenants to provide military service. Historians say there were many reasons for Jacobitism. Support for the Stuarts was the least important. Much of the support in the 1745 Rising came from Lowlanders who opposed the 1707 Union. Members of the Scottish Episcopal Church also supported it.

In 1745, most clan leaders told Prince Charles to go back to France. This included MacDonald of Sleat and Norman MacLeod. They felt Charles had not kept his promises by arriving without French military support. Also, Sleat and MacLeod were at risk from the government. They had been illegally selling tenants into indentured servitude.

Enough chiefs were persuaded to join. But the choice was rarely simple. Donald Cameron of Lochiel only joined after he was promised his estate's full value if the rising failed. MacLeod and Sleat later helped Charles escape after Culloden.

The Decline of the Clan System

In 1493, King James IV took the Lordship of the Isles from the MacDonalds. This made the region unstable. Links between Scottish MacDonalds and Irish MacDonnells meant unrest in one country often spread to the other. King James VI took steps to deal with this. This included the 1587 'Slaughter under trust' law. This law was later used in the 1692 Glencoe Massacre. To stop constant feuding, it required disputes to be settled by the Crown. This included murder committed in 'cold-blood' after a surrender or accepting hospitality. Its first use was in 1588. Lachlan Maclean was charged with murdering his new stepfather, John MacDonald, and 17 others.

Other measures had little effect. Making landowners financially responsible for their tenants' good behavior often failed. Many were not seen as the clan chief. The 1603 Union of the Crowns happened at the end of the Anglo-Irish Nine Years' War. This was followed by land seizures in 1608. The Plantation of Ulster aimed to bring stability to Western Scotland. It did this by bringing in Scottish and English Protestants. This process was often supported by the original owners. In 1607, Sir Randall MacDonnell settled 300 Presbyterian Scottish families on his land in Antrim. This ended the Irish practice of using Highland gallowglass, or mercenaries.

The 1609 Statutes of Iona put many rules on clan chiefs. These rules aimed to make them part of the Scottish landed gentry. While there is debate about their immediate effect, they influenced clan leaders in the long run. The Statutes made chiefs live in Edinburgh for much of the year. Their heirs had to be educated in the English-speaking Lowlands. Living in Edinburgh was expensive. The Highlands had little cash. This meant chiefs started to use their lands for money, rather than just managing them as a social system. The costs of living away from their clan lands led to chiefs being in debt. This eventually led to many Highland estates being sold in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

During the 1700s, chiefs wanted to earn more money from their estates. They began to limit the ability of tacksmen to sublet land. This meant more of the rent paid by farmers went directly to the landowner. This led to the removal of this layer of clan society. By the early 1800s, tacksmen were rare. Historian T. M. Devine calls this "one of the clearest demonstrations of the death of the old Gaelic society." Many tacksmen and wealthy farmers chose to emigrate. This was a way to resist changes in the Highland farming economy. The introduction of agricultural improvements led to the Highland clearances. The loss of this middle group of Highland society meant a loss of money and new ideas. The first big step in the clearances was when the Dukes of Argyll started auctioning off farm leases. This began in Kintyre in the 1710s and spread to all their lands after 1737. This action, acting as a commercial landlord, broke the principle of dùthchas.

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was once seen as the main reason for the end of clanship. After the uprising, there were harsh punishments against clans that supported the Jacobites. Laws were also made to destroy clan culture. However, historians now focus on chiefs slowly becoming landlords over a long time. The Jacobite rebellions, according to T.M. Devine, only paused the changes. The social changes after 1745 were just catching up with the financial pressures that led to landlordism. Laws after Culloden included the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746. This law took away the chiefs' right to hold courts and gave this role to judges. The traditional loyalty of clan members was probably not affected by this. There is also doubt about the real effect of banning Highland dress, which was repealed in 1782 anyway.

The Highland Clearances saw chiefs trying to get more money from their lands. In the first phase, many farmers were evicted and moved to new crofting communities, often by the coast. The small size of the crofts forced tenants to work in other industries, like fishing. With little work, more Highlanders became seasonal workers in the Lowlands. This made speaking English an advantage. It was found that when Gaelic schools started teaching Gaelic in the early 1800s, English literacy also increased. The Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) said in 1829: "so ignorant are the parents that it is difficult to convince them that it can be any benefit to their children to learn Gaelic, though they are all anxious... to have them taught English".

The second phase of the Highland clearances affected overcrowded crofting communities. These communities could no longer support themselves due to famine or industry collapse. Landlords provided "assisted passages" to poor tenants. This was cheaper than giving constant famine relief to those behind on rent. This happened especially in the Western Highlands and the Hebrides. Many Highland estates were no longer owned by clan chiefs. But landlords, both new and old, encouraged poor tenants to move to Canada and later Australia. The clearances were followed by even more emigration. This continued until the start of the Great Depression.

Romantic Revival

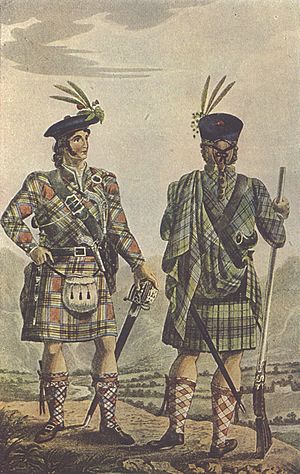

Most anti-clan laws were repealed by the end of the 1700s. The Jacobite threat had lessened. The Dress Act, which restricted kilt wearing, was repealed in 1782. Soon, Highland culture was revived. By the 1800s, ordinary people in the Highlands had mostly stopped wearing tartan. However, it was kept alive in the Highland regiments of the British army. Poor Highlanders joined these regiments in large numbers until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

The worldwide interest in tartan and a romantic view of the Highlands began with the Ossian cycle. This was published by James Macpherson (1736–96). Macpherson claimed to have found poems by an ancient bard named Ossian. His translations became popular internationally. Highland aristocrats set up Highland Societies in Edinburgh (1784) and London (1788). The romantic image of the Highlands became even more popular through the works of Walter Scott. His "staging" of King George IV's visit to Scotland in 1822, and the King wearing tartan, led to a huge demand for kilts and tartans. The Scottish linen industry could not keep up. Clan tartans were largely defined during this time. They became a major symbol of Scottish identity. This "Highlandism," where all of Scotland was identified with Highland culture, was cemented by Queen Victoria's interest in the country. She made Balmoral Castle a main royal retreat and was interested in "tartanry."

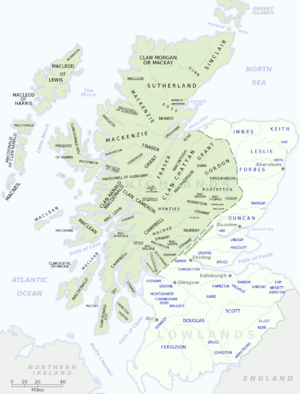

Clan Symbols

The renewed interest in clan ancestry led to lists and maps. These covered all of Scotland, showing clan names and territories, sometimes with their tartans. Some lists focus only on Highland clans. Others also show Lowland clans or families. Clan territories and loyalties changed over time. There are also different decisions on which smaller clans should be included.

This list of clans contains clans registered with the Lord Lyon Court. The Lord Lyon Court defines a clan or family as a legally recognized group. It does not differentiate between families and clans. Clans or families thought to have had a chief in the past but not currently recognized are listed at armigerous clans.

Clan Tartans

Tartans were traditionally linked to Highland Clans. After the Dress Act of 1746, which banned men and boys from wearing tartans, "district then clan tartans" became important. Almost all Scottish clans have more than one tartan for their surname. There are no strict rules on who can wear a particular tartan. Anyone can create a tartan and name it almost anything. However, only the chief has the authority to make a clan's tartan "official." Sometimes, after a chief's recognition, the clan tartan is recorded by the Lord Lyon. Once approved, it is recorded in the Lyon Court Books. In some cases, a clan tartan appears in the chief's heraldry. The Lord Lyon considers it the "proper" tartan of the clan.

Originally, tartans were not linked to specific clans. Highland tartans were made by local weavers in various designs. Any identification was regional. But the idea of a clan-specific tartan grew popular in the late 1700s. In 1815, the Highland Society of London began naming clan-specific tartans. Many clan tartans come from a 19th-century hoax called the Vestiarium Scoticum. This book was made by the "Sobieski Stuarts". They claimed it was an old manuscript of clan tartans. It has since been proven a fake. But despite this, the designs are still highly regarded. They continue to identify the clans.

Crest Badges

Wearing a crest badge shows loyalty to the clan chief. A crest badge for a clan member has the chief's heraldic crest. It is surrounded by a strap and buckle. It also has the chief's motto or slogan. People often say "clan crests," but there is no such thing. In Scotland, only individuals, not clans, have a heraldic coat of arms.

Any clan member can buy and wear crest badges. This shows their loyalty to their clan. But the heraldic crest and motto always belong only to the chief. These badges should only be used with the chief's permission. The Lyon Court has stepped in when permission was withheld. Scottish crest badges, like clan tartans, are not very old. They owe much to Victorian era romanticism. They have only been worn on the bonnet since the 1800s. The idea of a clan badge for identification might be true. It is often said that the original markers were just specific plants worn in bonnets or tied to a pole.

Clan Plant Badges

Clan badges are another way to show loyalty to a Scottish clan. These badges, sometimes called plant badges, are a sprig of a certain plant. They are usually worn in a bonnet behind the Scottish crest badge. They can also be attached to a lady's tartan sash at the shoulder. Or they can be tied to a pole and used as a standard. Clans that are historically connected, or lived in the same area, might share the same clan badge.

According to popular stories, clan badges were used by Scottish clans to identify each other in battle. However, the badges given to clans today might not be suitable for modern clan gatherings. Clan badges are often called the original clan symbol. But Thomas Innes of Learney said that the heraldic flags of clan chiefs were likely the earliest way to identify Scottish clans in battle or at large gatherings.

See also

- Armigerous clan

- Chief of the name

- Clan seat

- Clan

- Feud

- Gaels

- Gàidhealtachd

- Highland Clearances

- History of Scotland

- Irish clans

- List of Scottish clans

- Lord Lyon

- Scotia

- Scoto-Normans

- Scottish clan chief

- Scottish Gaelic

- Scottish names

- Scottish Heraldry

- Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs

- Statutes of Iona