History of the Philippines (1565–1898) facts for kids

The Spanish colonial period in the Philippines lasted from 1565 to 1898. During this time, the islands were ruled by Spain. They were part of the Captaincy General of the Philippines within the Spanish East Indies. At first, the Philippines was controlled by the Viceroyalty of New Spain (modern-day Mexico). This changed in 1821 when Mexico became independent. After that, Spain ruled the Philippines directly from Madrid.

The first time Europeans officially visited the Philippines was in 1521. This happened when Ferdinand Magellan arrived during his trip around the world. He was later killed in the Battle of Mactan. Forty-four years later, a Spanish group led by Miguel López de Legazpi came from Mexico. They began the Spanish takeover of the Philippines. Legazpi's group arrived in 1565. This was during the rule of Philip II of Spain, who the country is named after. Spanish rule officially started when Rajah Tupas surrendered. This led to the Treaty of Cebu on June 4, 1565.

The Spanish colonial period ended in 1898. Spain lost to the United States in the Spanish–American War. The Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898. This marked the start of the American colonial era in the Philippines.

Contents

How Spain Took Control

Early Explorations and Naming the Islands

Spaniards had been exploring the Philippines since the early 1500s. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese explorer working for Spain, was killed in 1521. He died fighting warriors led by datu Lapulapu at the Battle of Mactan. In 1543, another explorer, Ruy López de Villalobos, arrived. He named the islands of Leyte and Samar Las Islas Filipinas. This was to honor Philip II of Spain, who was then the Prince of Asturias. Philip became King of Spain in 1556. He ordered an expedition to conquer the Philippines for Spain.

The Conquest Under King Philip II

King Philip II ordered and watched over the conquest of the Philippines. On November 20, 1564, a Spanish group of about 500 men left Mexico. They were led by Miguel López de Legazpi. They arrived at Cebu on February 13, 1565. They took control of Cebu despite resistance from the local people. Many of these soldiers were from Tlaxcala, Mexico. They had helped Spain conquer Mexico. Some of them settled in the Philippines. Many Nahuatl words from Mexico became part of Filipino languages.

More than 15,000 soldiers came from Mexico in the 1600s. They were mostly criminals and young boys. Life was hard for these soldiers. They often looted and enslaved people. The Spanish Crown allowed the encomienda system. This system gave Spanish leaders control over native lands and people. Slavery was officially ended in the Spanish Empire. But it took about 100 years to fully stop it in the Philippines. This was because of the local alipin system of slavery already there.

Because of fights with the Portuguese and lack of supplies, Legazpi moved in 1569. He went to Panay and started a second settlement. In 1570, Legazpi sent his grandson, Juan de Salcedo, to Mindoro. Salcedo fought against Muslim pirates who were attacking villages.

In 1570, Martín de Goiti conquered Maynila on Luzon. Legazpi followed with a larger force of Spanish and Visayan soldiers. This large army made nearby Tondo surrender. Some local leaders tried to fight the Spanish in what was called the Tondo Conspiracy, but they failed. Legazpi renamed Maynila Nueva Castilla. He made it the capital of the Philippines. Legazpi became the first governor-general of the country.

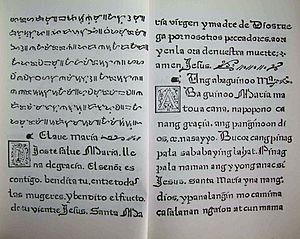

The Spanish slowly took control of different local states. They brought separate villages, called barangays, together into towns. This made it easier for Catholic missionaries to teach Christianity. Most people in the lowlands became Christian. Missionaries also started schools, a university, hospitals, and churches. To protect their settlements, the Spanish built many military forts. Spanish rule united most of the Philippines under one government.

From 1565 to 1821, the Philippines was ruled as part of New Spain in Mexico. After Mexico became independent, Spain ruled the Philippines directly from Madrid. The Philippines received money from the Spanish Crown in Mexico City each year. This money, about 250,000 pesos, often came as silver from Spanish America.

Japanese ships visited the Philippines in the 1570s to trade silver for gold. Later, they traded consumer goods. In the 1570s, Japanese pirates caused some trouble. But peaceful trade began between the Philippines and Japan by 1590. Japan's leader, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, tried to make the Philippines submit to Japan. He was not successful.

In 1597, King Philip II ordered that taxes taken from Filipinos unfairly should be returned. This order was published in Manila in 1598. King Philip died shortly after. A vote was held in 1599 where Filipinos recognized Spanish rule. This helped Spain establish its control over the Philippines.

Manila had about 1,200 Spanish families during the early colonial period. Cebu City received about 2,100 soldier-settlers from Mexico. Many soldiers from other parts of New Spain also came. However, most Filipinos remained native Austronesians. Spain kept its power in towns and cities. Mexicans were stationed in Ermita and Cavite near Manila. Soldiers from Peru were also sent to Zamboanga City to fight Muslim defenders.

Communities of Spanish-Mestizos (people of mixed Spanish and Filipino heritage) grew in Iloilo, Negros, and Vigan. The mixing of indigenous Filipinos and Spanish/Latin American immigrants led to a new language called Chavacano. This language is a mix of Mexican Spanish. People relied on the galleon trade for their living. Later, Governor-General José Basco y Vargas brought economic changes. These changes helped the colony earn money from tobacco and other farm products. Farming was then opened to Europeans, which had been only for Filipinos before.

Spain put down many local revolts. They also defended against outside attacks. Spain saw its fight with Muslims in Southeast Asia as a continuation of the Reconquista (the Christian reconquest of Spain). Wars against the Dutch in the 1600s and conflicts with Muslims in the south almost made the colony go bankrupt. Muslims from western Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago also raided Christian coastal areas. Settlers also had to fight off Chinese pirates. The most famous pirate was Limahong in 1573.

Dutch Attacks on the Philippines

There were three naval battles between Dutch pirates and Spanish forces. These were in 1610, 1617, and 1624. They are known as the First, Second, and Third Battles of Playa Honda. The second battle is the most famous. Both sides had about 10 ships. The Dutch lost their main ship and had to retreat. Only the third battle in 1624 was a Dutch victory.

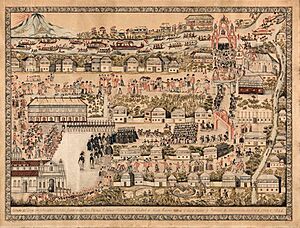

In 1646, five naval battles took place. These were called the Battles of La Naval de Manila. They were fought between Spain and the Dutch Republic during the Eighty Years' War. The Spanish forces had only two galleons and one galley. Their crews were mostly Filipino volunteers. The Dutch had three separate groups of ships, totaling eighteen vessels. But the Spanish-Filipino forces badly defeated the Dutch. This made the Dutch give up their plans to invade the Philippines.

On June 6, 1647, Dutch ships were seen near Mariveles Island. Spain had only one galleon and two galleys ready to fight. The Dutch had twelve large ships. On June 12, the Dutch attacked the Spanish port of Cavite. The battle lasted eight hours. The Spanish believed they damaged the Dutch ships a lot. Spanish ships were not badly damaged, and few people were hurt. However, almost every roof in the Spanish settlement was damaged by cannon fire. The cathedral was especially targeted.

On June 19, the Dutch fleet split up. Six ships went to the shipyard of Mindoro. The other six stayed in Manila Bay. The Dutch then attacked Pampanga. They captured a fortified monastery, took prisoners, and killed almost 200 Filipino defenders. The governor ordered funerals for the dead and payments to their families.

The next year, an expedition arrived in Jolo in July. The Dutch had teamed up with an anti-Spanish king, Salicala. The Spanish soldiers on the island were few, but they survived a Dutch attack. The Dutch finally left. The Spanish made peace with the people of Jolo and then also left.

There was also a failed attack on Zamboanga in 1648. That year, the Dutch promised the people of Mindanao that they would return in 1649. They promised to help them revolt against the Spanish. Several revolts did happen. The most serious was in the village of Lindáo. Most of the Spaniards there were killed. The survivors had to escape in a small boat. However, the Dutch help never came. The authorities in Manila offered a general pardon. Many Filipinos in the mountains then surrendered.

These wars may have caused the population to decrease.

British Occupation of Manila

In August 1759, Charles III became the King of Spain. At that time, Great Britain and France were fighting in the Seven Years' War.

British forces took over Manila from 1762 to 1764. However, they could not expand their control outside Manila. Filipinos stayed loyal to the Spanish community outside the city. Spanish colonial forces kept the British only in Manila. Catholic Archbishop Manuel Rojo, who was captured by the British, signed a surrender document on October 30, 1762. This made the British confident they would win.

But Don Simón de Anda y Salazar rejected the surrender. He said it was illegal. He claimed to be the true Governor-General. He led Spanish-Filipino forces that kept the British stuck in Manila. He also stopped British-supported revolts, like the one led by Diego Silang. Anda also changed the route of the Manila galleon trade. This prevented the British from capturing more ships. The British failed to strengthen their position. Their troops left, and their command broke down. This left the British forces weak.

The Seven Years' War ended with the Peace of Paris on February 10, 1763. When the treaty was signed, no one knew that Manila was under British control. So, the Philippines was not specifically mentioned. Instead, it fell under a general rule. This rule said that all other lands not mentioned would be returned to Spain.

Philippines Opens to World Trade

In the 1800s, factories grew in Europe and North America. This led to a higher demand for raw materials. Even though the Philippines was only allowed to trade with Spain, this demand changed things. Spain, under Governor-General José Basco, opened the ports to international trade. The Philippines became a source of raw materials and a market for goods.

After 1834, when Philippine ports opened, Filipino society began to change. The decline of the Manila Galleon trade also affected the local economy. Land that was once shared became private. This was to meet the global demand for farm products. This led to the official opening of ports in Manila, Iloilo, and Cebu for international trade.

The Rise of Filipino Nationalism

The Philippines becoming a source of raw materials and a market for European goods created much wealth. Many Filipinos became rich. Everyday Filipinos also benefited. There was a quick increase in demand for workers and new business chances. Some Europeans moved to the Philippines to join this wealth. One was Jacobo Zobel, whose family is now very important in the Philippines. Their children studied in Europe's best universities. There, they learned about freedom from the French and American Revolutions. This new economy created a new middle class in the Philippines.

In the mid-1800s, the Suez Canal opened. This made it easier to travel from Spain to the Philippines. More Peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) came to the Philippines. This threatened the local Catholic churches. In government, Criollos (Spaniards born in the Philippines, called Insulares) lost their jobs to the Peninsulares. The Insulares saw the Peninsulares as foreigners.

The wars for independence in Spanish America and new immigration changed how people saw themselves. The term Filipino began to mean all people in the Philippines. Before, it only meant Spaniards born in Spain or the Philippines. This new identity was pushed by rich families of mixed heritage. It grew into a national identity.

The Insulares started to feel more Filipino. They called themselves Los hijos del país (meaning "sons of the country"). Early supporters of Filipino nationalism included Padre Pedro Peláez. He fought for Philippine churches to be run by local priests. Padre José Burgos, whose death influenced José Rizal, also supported this. Joaquín Pardo de Tavera fought for local people to keep government jobs. In response, the Spanish friars called the Indios (Filipinos) lazy and unfit for jobs. The Insulares wrote Indios agraviados. This was a statement defending Filipinos against unfair comments.

The tension between the Insulares and Peninsulares led to failed revolts. These included the Novales revolt and the Cavite mutiny of 1872. Many Filipino nationalists were sent away to the Marianas and Europe. They continued to fight for freedom through the Propaganda Movement. The Cavite Mutiny involved priests Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora (known as Gomburza). Their deaths inspired the next generation of Filipino nationalists, like José Rizal. He dedicated his novel El filibusterismo to these priests.

A national public school system started in 1863.

The Rise of Spanish Liberalism

After Liberals won the Spanish Revolution of 1868, Carlos María de la Torre became governor-general (1869–1871). He was very popular because of the good changes he made. His supporters, including Padre Burgos, even sang to him outside the Malacañan Palace. When the Liberals lost power in Spain, de la Torre was replaced. Governor-General Izquierdo took over. He promised to rule strictly.

Educated Filipinos, Rizal, and the Katipunan

Feelings for revolution grew in 1872. This was after three activist Catholic priests were killed on weak charges. This inspired a propaganda movement in Spain. Marcelo H. del Pilar, José Rizal, and Mariano Ponce led this movement. They pushed for political changes in the Philippines.

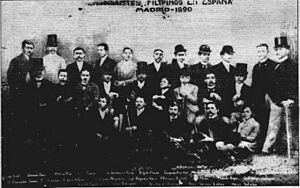

Many nationalists were sent away to the Marianas and Europe in 1872. This created a group of Filipino reformers in Europe. More educated Filipinos, called Ilustrados, studied in European universities. They worked with Spanish liberals and started the newspaper La Solidaridad. During this time, Spain also displayed indigenous Filipinos in "human zoos" for white audiences. This made the call for revolution even stronger.

José Rizal was one of these reformers. He wrote two novels while in Europe. His novels were very important. They caused more unrest in the Philippines. This led to the founding of the Katipunan. Rizal returned to the Philippines to start La Liga Filipina. This group aimed to bring the reform movement to the Philippines. He was arrested just days after starting it. Rizal was later killed on December 30, 1896, accused of rebellion. His death made many people who were loyal to Spain become revolutionaries.

As attempts at reform failed, radical members of La Liga Filipina formed a new group in 1892. This group was called the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (KKK), or simply the Katipunan. Its goal was for the Philippines to break away from Spain. Andrés Bonifacio and Deodato Arellano were among its founders.

The Philippine Revolution

By 1896, the Katipunan had thousands of members. That same year, Spanish authorities found out about the Katipunan. In late August, Katipuneros gathered in Caloocan. They declared the start of the revolution. This event is known as the Cry of Balintawak or Cry of Pugad Lawin. Andrés Bonifacio called for an attack on Manila. He was defeated in battle at San Juan del Monte. He gathered his forces again. He briefly captured the towns of Marikina, San Mateo, and Montalbán. Spanish counterattacks pushed him back. He retreated and fought using guerrilla warfare.

By August 30, the revolt had spread to eight provinces. Governor-General Ramón Blanco declared a state of war in these provinces. They were Manila, Bulacan, Cavite, Pampanga, Tarlac, Laguna, Batangas, and Nueva Ecija. These provinces are shown by the eight rays of the sun on the Filipino flag. Emilio Aguinaldo and the Katipuneros of Cavite were the most successful rebels. They controlled most of their province by September–October. They defended their areas with trenches designed by Edilberto Evangelista.

Many educated Filipinos, like Antonio Luna and Apolinario Mabini, did not want an armed revolution at first. José Rizal himself, who inspired the rebels, did not approve of a revolution too soon. He was arrested, tried, and killed for rebellion on December 30, 1896. Before his arrest, he had said he did not support the revolution. But in his farewell poem Mi último adiós, he wrote that dying for one's country in battle was just as patriotic as his own coming death.

While the revolution spread, Aguinaldo's Katipuneros declared their own government in October. Bonifacio had already made the Katipunan an insurgent government with him as president in August. Bonifacio was asked to come to Cavite. He was to help settle disagreements between Aguinaldo's rebels, the Magdalo, and their rivals, the Magdiwang. Both were chapters of the Katipunan. There, he got involved in talks about replacing the Katipunan with a new government. This led to the Tejeros Convention. In an election, Bonifacio lost his position. Emilio Aguinaldo was chosen as the new leader of the revolution. On March 22, 1897, the Tejeros Revolutionary Government was formed. Bonifacio refused to accept this. He and others signed the Naic Military Agreement. This led to his death for treason in May 1897. On November 1, the Tejeros government was replaced by the Republic of Biak-na-Bato.

By December 1897, the revolution was at a standstill. Pedro Paterno helped the two sides sign the Pact of Biak-na-Bato. This agreement included Aguinaldo and his officers going into exile. In return, the Spanish government would pay $MXN 800,000. Aguinaldo then sailed to Hong Kong.

The Spanish–American War

On April 25, 1898, the Spanish–American War began. On May 1, 1898, the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Squadron, led by Commodore George Dewey, defeated the Spanish navy in the Battle of Manila Bay. With its navy gone and control of Manila Bay lost, Spain could no longer defend Manila or the Philippines.

On May 19, Emilio Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines on a U.S. Navy ship. On May 24, he took command of Filipino forces. Filipino forces had freed much of the country from Spain. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared the Philippine Declaration of Independence from Spain. Filipino forces then surrounded Manila, as did American forces.

In August 1898, the Spanish governor-general secretly agreed with American commanders. He would surrender Manila to the Americans after a fake battle. On August 13, 1898, during the Battle of Manila, Americans took control of the city. In December 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed. This ended the Spanish–American War. It also sold the Philippines to the United States for $20 million. With this treaty, Spanish rule in the Philippines officially ended.

On January 23, 1899, Aguinaldo established the First Philippine Republic in Malolos.

It became clear that the United States would not recognize the First Philippine Republic. So, the Philippine–American War began on February 4, 1899, with the Battle of Manila.

Images for kids

-

Tomb of Miguel López de Legazpi, founder of Manila as the capital city of the Philippine islands, located in Manila at the San Agustin Church inside the historic walled city of Intramuros

-

The two merchant galleons, Encarnacion and Rosario, which were hastily converted to warships to meet the superior Dutch armada of 18 vessels during the battles of La Naval de Manila in 1646 (artist's conception)

-

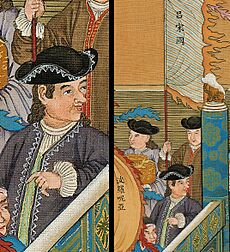

Luzon island (吕宋国) delegates in Beijing, China, in 1761. 万国来朝图

-

Emilio Aguinaldo, the first Philippine president

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |