Alexander the Great facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Alexander the Great |

|

|---|---|

| Basileus | |

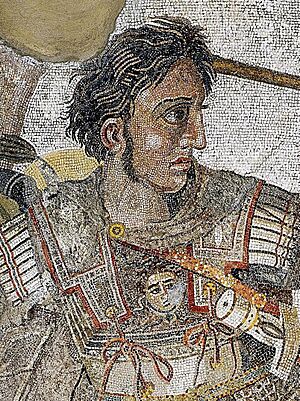

Detail from the Alexander Mosaic (created c. 120–100 BCE)

|

|

| King of Macedon | |

| Reign | October 336 – June 323 BC |

| Predecessor | Philip II |

| Successor | Philip III |

| Hegemon of the Hellenic League, Strategos Autokrator of Greece | |

| Reign | 336–323 BC |

| Predecessor | Philip II |

| Successor | Demetrius I |

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

| Reign | 332–323 BC |

| Predecessor | Darius III |

| Successor | Philip III |

| King of Persia | |

| Reign | 330–323 BC |

| Predecessor | Darius III |

| Successor | Philip III |

| Born | 20 or 21 July 356 BC Pella, Macedon |

| Died | 10 or 11 June 323 BC (aged 32) Babylon, Macedon |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | 3, including

|

| Greek | Ἀλέξανδρος |

| Dynasty | Argead |

| Father | Philip II of Macedon |

| Mother | Olympias of Epirus |

| Religion | Ancient Greek religion |

Alexander III of Macedon, known as Alexander the Great, was a powerful king from ancient Greece. He became king at 20 after his father, Philip II, died in 336 BC. For most of his rule, he led his army on long journeys across Western Asia, Central Asia, parts of South Asia, and Egypt. By the time he was 30, he had built one of the biggest empires ever, reaching from Greece all the way to India. He never lost a battle and is remembered as one of history's most successful military leaders.

The famous philosopher Aristotle taught Alexander until he was 16. Soon after becoming king in 335 BC, Alexander secured his northern borders. He also united the Greek cities under his leadership to prepare for a big war against the Persian Empire, just as his father had planned.

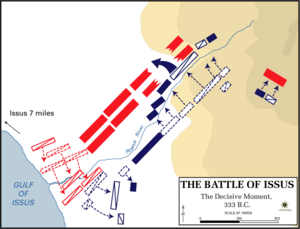

In 334 BC, Alexander invaded the mighty Persian Empire. For 10 years, he led his army through many battles, like those at Issus and Gaugamela. He defeated King Darius III and took over the entire Persian Empire. His empire now stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River. Alexander wanted to explore even further, so he marched into India in 326 BC. There, he won a major battle against King Porus. However, his soldiers were tired and missed home, so they refused to go further. Alexander turned back and later died in Babylon in 323 BC, at just 32 years old.

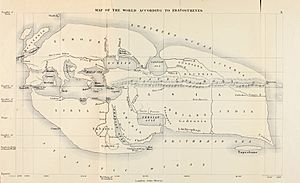

Alexander's death began the Hellenistic period, a time when Greek culture spread far and wide. His conquests mixed Greek ideas with those of other lands, creating new cultures. He founded over twenty cities, with Alexandria in Egypt being the most famous. Greek settlers and their culture spread across his empire, influencing places as far as India. This Hellenistic culture later shaped the Roman Empire and much of Western culture today. Greek became a common language in the region for centuries.

Alexander became a legendary hero, much like Achilles. His amazing military victories made him a role model for many future leaders. Even today, his battle strategies are studied in military schools worldwide. Stories about Alexander grew into the Alexander Romance, a popular collection of tales translated into many languages around the world.

Alexander's Early Life

Growing Up in Pella

Alexander III was born in Pella, the capital of the Kingdom of Macedon, around July 20, 356 BC. His father was Philip II, the king of Macedon, and his mother was Olympias, a princess from Epirus. Olympias was Philip's main wife for a time, especially after Alexander was born.

On the day Alexander was born, Philip received news of military victories and that his horses had won at the Olympic Games. It was also said that the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, burned down that day. Some said this happened because the goddess Artemis was away, attending Alexander's birth.

Alexander was raised by a nurse named Lanike. Later, he was taught by Leonidas, a relative of his mother, and by Lysimachus. He learned to read, play the lyre, ride horses, fight, and hunt, just like other noble Macedonian youths.

Aristotle, His Famous Teacher

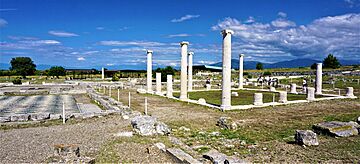

When Alexander was 13, Philip looked for a special teacher for his son. He chose Aristotle, one of the most famous philosophers in history. Philip provided the Temple of the Nymphs at Mieza as a classroom. In return, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown, which he had destroyed, and free its former citizens.

Mieza became like a boarding school for Alexander and other young Macedonian nobles. These students, including Ptolemy, Hephaestion, and Cassander, became Alexander's friends and future generals, often called his "Companions." Aristotle taught them about medicine, philosophy, morals, religion, logic, and art. Under Aristotle, Alexander developed a great love for the works of Homer, especially the Iliad.

Becoming King

Taking the Throne

Alexander's education with Aristotle ended when he was 16. His father, Philip II, was often away fighting wars. During these times, Alexander was left in charge as regent, meaning he ruled in his father's place. Once, when Philip was away, a Thracian tribe revolted, and Alexander quickly defeated them.

Alexander also helped his father in battles. He reportedly saved Philip's life during a campaign against the city of Perinthus. Philip then planned to intervene in Greek affairs and ordered Alexander to gather an army. To trick other Greek states, Alexander made it seem like he was preparing to attack Illyria instead.

In 338 BC, Philip and Alexander joined forces and marched south into Greece. They occupied the city of Elatea, close to Athens and Thebes. Athens and Thebes formed an alliance against Macedon. Philip offered peace, but they refused.

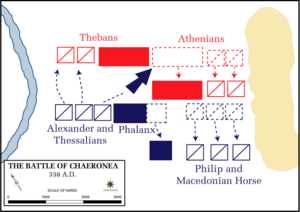

Philip's army met their opponents at the Battle of Chaeronea. Philip commanded the right side, and Alexander led the left. The battle was fierce. Philip cleverly ordered his troops to pretend to retreat, causing the Athenian soldiers to break their lines and follow. Alexander was the first to break through the Theban lines. With the enemy's formation broken, Philip's army quickly defeated them.

After this victory, Philip and Alexander marched into the Peloponnese. In Corinth, Philip created a "Hellenic Alliance" of most Greek city-states, except Sparta. Philip was named Hegemon (Supreme Commander) of this league and announced his plans to attack the Persian Empire.

Challenges to His Claim

When Philip returned to Pella, he married Cleopatra Eurydice. This marriage made Alexander's position as heir less secure, as any son born to Cleopatra would be fully Macedonian, while Alexander's claim was seen as less direct. At the wedding feast, Cleopatra's uncle, Attalus, made a rude comment about Alexander's right to the throne. Alexander, angered, threw a cup at Attalus. Philip, taking Attalus's side, tried to attack Alexander but stumbled and fell. Alexander then mocked his father.

In 337 BC, Alexander left Macedon with his mother, Olympias. He sought refuge with some Illyrian kings. However, Philip likely never intended to disown his skilled son. After six months, Alexander returned to Macedon thanks to a family friend who helped them reconcile.

The next year, a Persian governor offered his daughter to Alexander's half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus. Olympias and Alexander's friends thought this meant Philip planned to make Arrhidaeus his heir. Alexander reacted by trying to arrange his own marriage to the daughter. Philip stopped these plans and exiled four of Alexander's friends, saying he wanted a better bride for Alexander.

Alexander's Reign Begins

Becoming King of Macedon

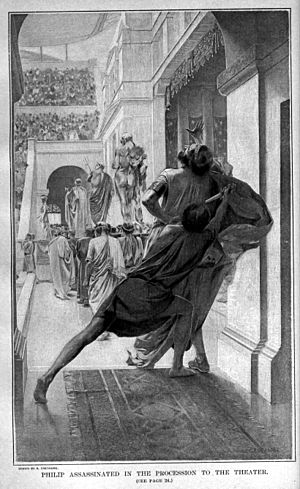

In October 336 BC, while attending his daughter's wedding, Philip II was killed by one of his bodyguards, Pausanias. As Pausanias tried to escape, he tripped and was killed by Alexander's companions. Alexander was immediately proclaimed king by the nobles and the army at the age of 20.

Securing His Power

Alexander began his rule by removing anyone who might challenge his throne. He had his cousin, the former king Amyntas IV, executed. He also had two Macedonian princes killed for being involved in his father's assassination. Alexander's mother, Olympias, had Philip's new wife and their baby daughter killed. When Alexander found out, he was furious. Alexander also had Attalus, a general who had insulted him, killed. He spared Arrhidaeus, who was mentally disabled.

News of Philip's death caused many states, including Thebes and Athens, to revolt. Alexander responded quickly. He gathered 3,000 Macedonian cavalry and rode south. He surprised the Thessalian army, who quickly surrendered and joined his forces. He then continued towards the Peloponnese.

Alexander stopped at Thermopylae and was recognized as the leader of the Amphictyonic League. He then went to Corinth. Athens asked for peace, and Alexander pardoned the rebels. During his stay in Corinth, Alexander met the famous philosopher Diogenes the Cynic. When Alexander asked Diogenes if he could do anything for him, Diogenes simply asked Alexander to move aside, as he was blocking the sunlight. Alexander was reportedly delighted by this reply, saying, "If I were not Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes." In Corinth, Alexander took the title of Hegemon (leader) and was appointed commander for the upcoming war against Persia.

Campaigns in the North

Before crossing into Asia, Alexander wanted to make sure his northern borders were safe. In the spring of 335 BC, he marched to put down several revolts. He traveled east into the land of the Thracians and defeated their forces. The Macedonians then marched into the country of the Triballi and defeated their army near the Lyginus river. Alexander then reached the Danube River and surprised the Getae tribe on the opposite shore, forcing them to retreat.

News then reached Alexander that Illyrian chieftains were rebelling. Marching west into Illyria, Alexander defeated them, forcing the rulers to flee. With these victories, he secured his northern frontier.

The Fall of Thebes

While Alexander was campaigning in the north, the cities of Thebes and Athens rebelled again. Alexander immediately headed south. While other cities hesitated, Thebes decided to fight. The Theban resistance was not strong enough, and Alexander destroyed the city, dividing its land among other cities. The destruction of Thebes made Athens and the rest of Greece temporarily peaceful. Alexander then began his Asian campaign, leaving his general Antipater in charge of Macedon.

Conquering the Persian Empire

Alexander's Battle Strategy

Alexander's invasion of Persia is a great example of smart military planning. He first secured his base in Greece and the Balkans. Then, he conquered the Afro-Asian coastline, which was where the Persian fleet was based. This protected his army from attacks from behind. Only then did he directly confront the Persians. He solved the problem of fighting deep in enemy territory in a brilliant way.

Victories in Asia Minor

In 334 BC, Alexander's army crossed into Asia. He showed his determination to conquer the Persian Empire by throwing a spear into Asian soil. He declared that he accepted Asia as a gift from the gods.

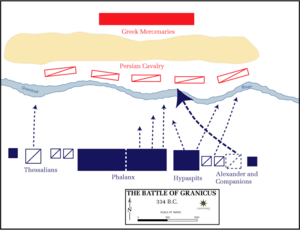

After an early victory against Persian forces at the Battle of the Granicus, Alexander took control of the Persian city of Sardis. He then moved along the coast, giving freedom to many Greek cities. He captured Miletus and then Halicarnassus after difficult sieges. Alexander left the government of Caria to a local ruler named Ada, who adopted him.

From Halicarnassus, Alexander moved inland. At the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordium, Alexander faced the famous Gordian Knot. A legend said that whoever could untie this complex knot would become the king of Asia. Alexander, instead of untying it, simply cut it in half with his sword, declaring that it didn't matter how it was undone.

March Through the Levant and Egypt

In spring 333 BC, Alexander crossed the Taurus Mountains into Cilicia. After recovering from an illness, he marched towards Syria. He defeated Darius's much larger army at the Battle of Issus. Darius fled the battle, leaving his family and treasure behind. He offered a peace treaty, but Alexander replied that since he was now king of Asia, he would decide who ruled what. Alexander then took control of Syria and most of the coast.

In 332 BC, he faced strong resistance at Tyre. He captured the city after a long and difficult siege. After a tough fight, the city was captured. Many people were killed or taken as captives.

Alexander then advanced into Egypt in late 332 BC, where he was welcomed as a liberator. Most towns on the way quickly surrendered. However, he met resistance at Gaza, a heavily fortified city on a hill. After three difficult attacks, the city fell. As in Tyre, many people were killed or taken as captives.

To show his right to rule and be seen as a true pharaoh, Alexander made sacrifices to the gods in Memphis. He also visited the famous oracle of Amun-Ra at the Siwa Oasis in the desert. There, he was declared the son of the god Amun. From then on, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father.

During his time in Egypt, he founded the city of Alexandria, which would become a very important capital after his death. Alexander restored temples and dedicated new monuments to the Egyptian gods. He also reformed the tax system. In early 331 BC, he left Egypt to continue his pursuit of the Persians.

Defeating Darius and Taking Persia

Leaving Egypt in 331 BC, Alexander marched east into Upper Mesopotamia (modern-day northern Iraq). He defeated Darius again at the Battle of Gaugamela. Darius fled once more, and Alexander chased him. Gaugamela was the final and decisive battle between the two kings. Alexander then captured Babylon.

From Babylon, Alexander went to Susa, one of the Persian capitals, and captured its treasury. He sent most of his army to the ceremonial capital of Persepolis. Alexander himself took a direct route to the city, storming the pass of the Persian Gates which was blocked by a Persian army. He reached Persepolis before its defenders could loot the treasury.

Upon entering Persepolis, Alexander allowed his troops to loot the city for several days. During his five-month stay, a fire broke out in the palace and spread throughout the city. Some say it was an accident, others that it was revenge for the Persians burning Athens years before. Alexander soon regretted the decision to burn the city.

Alexander then chased Darius, who was taken prisoner by Bessus, his Bactrian governor. Bessus had Darius fatally stabbed and declared himself the new king. Alexander buried Darius's remains with a royal funeral. He claimed that Darius, before dying, had named him as his successor to the Persian throne.

Alexander saw Bessus as a usurper and set out to defeat him. This campaign led Alexander on a grand tour of Central Asia. He founded many new cities, all called Alexandria, including modern Kandahar in Afghanistan. In 329 BC, Bessus was betrayed and executed. However, another leader named Spitamenes started a revolt. Alexander defeated Spitamenes, who was then killed by his own men.

Challenges and Plots

Alexander faced plots against his life. One of his officers, Philotas, was executed for not reporting a plot. This led to the death of Philotas's father, Parmenion, who was a trusted general. Most famously, Alexander, in a fit of anger, killed his friend Cleitus the Black during an argument. Cleitus had accused Alexander of forgetting Macedonian ways in favor of Persian ones.

Later, another plot was discovered, started by his own royal pages. His official historian, Callisthenes, was involved. Callisthenes and the pages were punished severely and likely died soon after.

While Alexander was in Asia, his general Antipater was in charge of Macedon. Greece remained mostly peaceful. Alexander sent back vast amounts of wealth from his conquests, which helped the economy. However, Alexander's constant need for troops and the migration of Macedonians across his empire weakened Macedon in the long run.

Alexander's Journey to India

Exploring New Lands

After securing his new territories and marrying Roxana, Alexander turned his attention to the Indian subcontinent. He invited local leaders to submit to his rule. Ambhi, the ruler of Taxila, agreed and offered Alexander valuable gifts and his army's help. Alexander returned Ambhi's gifts and title, and even gave him more presents.

Ambhi helped Alexander build a bridge over the Indus River and provided supplies. He welcomed Alexander and his army to Taxila. Ambhi later joined Alexander in the Battle of the Hydaspes.

In the winter of 327/326 BC, Alexander led campaigns against several hill tribes. He was wounded in the shoulder by a dart during a fierce fight. He then faced the Assakenoi, who fought from strongholds like Massaga and Ora. Massaga was captured after bloody fighting, and Alexander was seriously wounded in the ankle. A similar fight happened at Ora. Many Assakenians fled to the fortress of Aornos, which Alexander captured after four difficult days.

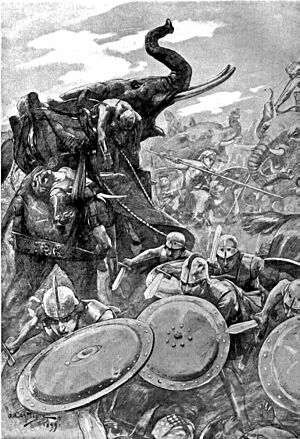

After Aornos, Alexander crossed the Indus River and fought an epic battle against King Porus. Porus ruled a region in what is now Punjab, India. Alexander won the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC. Alexander was impressed by Porus's bravery and made him an ally, even giving him more territory to rule. This helped Alexander control lands far from Greece. Alexander founded two cities on opposite sides of the Hydaspes river. He named one Bucephala, in honor of his horse, Bucephalus, who died around this time. The other was Nicaea (Victory).

The Army's Decision to Turn Back

East of Porus's kingdom were other powerful empires. Alexander's army was tired after years of campaigning and feared facing more large armies. They refused to march further east at the Hyphasis River (Beas). This river marks the easternmost point of Alexander's conquests.

Alexander tried to convince his soldiers to continue, but his general Coenus pleaded with him to turn back. The men, he said, "longed to again see their parents, their wives and children, their homeland." Alexander finally agreed. He turned south, marching along the Indus River. Along the way, his army conquered other Indian tribes. While besieging a city, Alexander suffered a serious injury when an arrow pierced his armor and entered his lung.

Alexander sent much of his army back to Persia with general Craterus. He also sent a fleet to explore the Persian Gulf coast under his admiral Nearchus. Alexander led the rest of his army back to Persia through the difficult Gedrosian Desert. Many men were lost in the harsh desert. Alexander reached Susa in 324 BC.

The End of a Great Reign

Alexander's Final Years

When Alexander returned to Persia, he found that many of his governors and military leaders had misbehaved in his absence. He executed several of them as examples. As a gesture of thanks, he paid off his soldiers' debts. He also announced that he would send older and disabled veterans back to Macedon.

His troops misunderstood his intentions and rebelled at the town of Opis. They refused to be sent away and criticized his adoption of Persian customs and the inclusion of Persian officers in Macedonian units. After three days, Alexander gave command posts to Persians. The Macedonians quickly begged for forgiveness, which Alexander accepted. He held a large banquet with thousands of his men.

To create lasting harmony between his Macedonian and Persian subjects, Alexander arranged a mass marriage of his senior officers to Persian noblewomen at Susa. However, few of these marriages lasted long.

Upon his return to Persia, Alexander learned that guards had disrespected the tomb of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae. He admired Cyrus the Great and swiftly punished the guards. Alexander ordered his architect to decorate the tomb's interior.

Afterwards, Alexander traveled to Ecbatana. There, his closest friend, Hephaestion, died of illness. Hephaestion's death deeply saddened Alexander. He ordered an expensive funeral in Babylon and a period of public mourning. Back in Babylon, Alexander planned new campaigns, starting with an invasion of Arabia.

His Mysterious Death

Alexander died in the palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon on June 10 or 11, 323 BC, at the age of 32. There are slightly different accounts of his death. One says that about 14 days before he died, Alexander developed a fever that worsened until he couldn't speak. His soldiers were allowed to pass by him as he silently waved. Another account says he was struck with pain after drinking wine and suffered for 11 days before dying.

Because Alexander was young and powerful, many theories about his death involved foul play. Some ancient writers mentioned the theory that Alexander was poisoned. They suggested that Antipater, a general who had been removed from his position, might have arranged for his son Iollas, Alexander's wine-pourer, to poison him. Even the philosopher Aristotle was sometimes mentioned in these theories. However, the fact that Alexander was ill for twelve days makes a quick-acting poison unlikely. Modern theories suggest he might have been poisoned by a plant called white hellebore or by a dangerous compound in water from the river Styx.

Many natural causes have also been suggested, such as malaria, typhoid fever, acute pancreatitis, or Guillain-Barré syndrome. It's also thought that Alexander's health might have been declining due to years of severe wounds and the deep sadness he felt after Hephaestion's death.

What Happened After Alexander's Death?

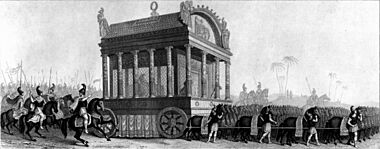

Alexander's body was placed in a gold coffin filled with honey. A seer predicted that the land where Alexander was buried would be "happy and unconquerable forever." His generals likely saw possession of his body as a symbol of their right to rule.

While Alexander's funeral procession was on its way to Macedon, Ptolemy, one of his generals, seized it and took it to Memphis in Egypt. Later, the coffin was moved to Alexandria, where it remained for centuries.

Alexander's death was so sudden that when news reached Greece, people didn't believe it at first. Alexander had no clear heir. His son, Alexander IV of Macedon, was born after his death. According to one story, when asked who should inherit his kingdom, Alexander replied, "To the strongest." Another story says he passed his signet ring to Perdiccas, a bodyguard, naming him as his successor.

Perdiccas initially suggested that Roxana's baby should be king, with several generals as guardians. However, the infantry wanted Alexander's half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, to be king. Eventually, both Alexander IV and Philip III were appointed joint kings, though they had little real power. Rivalry soon broke out among Alexander's generals, known as the Diadochi (Successors). After Perdiccas was killed in 321 BC, Alexander's empire broke apart. For 40 years, the Diadochi fought wars, eventually dividing the Hellenistic world into three main kingdoms: Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucid Syria and the East, and Antigonid Macedon. Both Alexander IV and Philip III were murdered during these conflicts.

Alexander's Amazing Legacy

A Masterful Military Leader

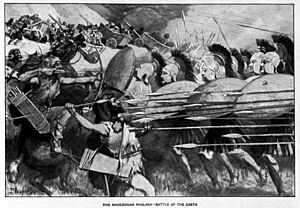

Alexander earned the title "the Great" because of his incredible success as a military commander. He never lost a battle, even when his army was outnumbered. He achieved this by using the terrain wisely, employing clever tactics with his phalanx (a tight formation of soldiers with long spears) and cavalry, and inspiring fierce loyalty in his troops. The Macedonian phalanx, with its six-meter-long spears called sarissas, was perfected by his father, Philip II. Alexander used its speed and maneuverability very effectively against larger Persian forces.

In his first battle in Asia, at Granicus, Alexander used only a small part of his forces against a much larger Persian army. He placed his phalanx in the center and cavalry and archers on the sides. This prevented the Persians from surrounding his army. The Macedonian losses were very small compared to the Persians'.

At Issus in 333 BC, Alexander's first major fight with Darius, he used the same formation. The central phalanx pushed through, and Alexander personally led the charge, causing the enemy army to flee. In the decisive battle of Gaugamela, Darius used chariots with scythes on their wheels. Alexander arranged his phalanx to open up when the chariots attacked, then reformed to trap them. This strategy broke Darius's center, and he fled again.

When Alexander faced enemies with different fighting styles, like in Central Asia and India, he adapted his army. In India, when confronted by King Porus's war elephants, the Macedonians opened their ranks to surround the elephants. They used their long spears to strike upwards and dislodge the elephant handlers.

Spreading Greek Culture

Alexander's most direct legacy was bringing Macedonian rule to vast new areas of Asia. Many of these regions remained under Greek influence for the next 200–300 years. This period is often called the Hellenistic period.

The spread of Greek language, culture, and people into the former Persian Empire after Alexander's conquests is known as Hellenization. This process can be seen in great Hellenistic cities like Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch, and Seleucia. Alexander wanted to mix Greek and Persian cultures. Although his successors didn't always follow this idea, Hellenization happened throughout the region.

The main part of Hellenistic culture came from Athens. The close contact between men from different parts of Greece in Alexander's army led to the development of "Koine" or "common" Greek. Koine spread throughout the Hellenistic world, becoming the common language and eventually the ancestor of modern Greek. Town planning, education, local government, and art during the Hellenistic period were all based on Classical Greek ideas.

Hellenization in Asia

Some of the clearest effects of Hellenization can be seen in Afghanistan and India. In these regions, Greek culture mixed with Iranian and Buddhist cultures. The art and mythology of Gandhara (a region in modern Pakistan) show direct contact between Hellenistic civilization and South Asia. The Edicts of Ashoka, ancient Indian inscriptions, even mention Greeks in Ashoka's kingdom converting to Buddhism.

This mixing of cultures, known as Greco-Buddhism, influenced the development of Buddhism. Some of the first statues of The Buddha appeared at this time, possibly modeled on Greek statues of Apollo. Some Buddhist traditions might have been influenced by ancient Greek religion, such as the idea of Bodhisattvas (divine heroes) being similar to Greek heroes. One Greek king, Menander I, likely became Buddhist and is remembered in Buddhist writings as 'Milinda'.

Cities Named After Alexander

During his conquests, Alexander founded many cities that bore his name. Most of these were east of the Tigris River. The first and greatest was Alexandria in Egypt, which became one of the most important cities in the Mediterranean. The cities were often located along trade routes or in good defensive spots.

At first, these cities were probably just military outposts. After Alexander's death, many Greeks who had settled there tried to return home. However, about a century later, many Alexandrias were thriving. They had impressive public buildings and large populations of both Greek and local peoples.

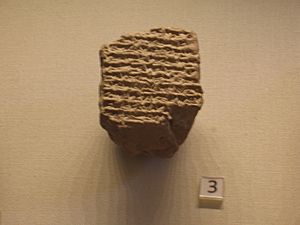

In 334 BC, Alexander donated money to finish the new temple of Athena Polias in Priene, in modern-day Turkey. An inscription from the temple, now in the British Museum, says: "King Alexander dedicated [this temple] to Athena Polias." This inscription is one of the few archaeological finds that confirms an event from Alexander's life.

Alexander in Legends and Stories

Many legends about Alexander began during his lifetime, probably encouraged by Alexander himself. His court historian, Callisthenes, wrote that the sea in Cilicia drew back from him as a sign of respect.

In the centuries after Alexander's death, many of these legendary stories were collected into a text called the Alexander Romance. This book was translated into many languages across the Islamic and European worlds. It contains many exciting, though sometimes unbelievable, stories about Alexander.

Alexander the Great's achievements and legacy have been shown in many cultures. He appears in modern Greek folklore more than any other ancient figure. A well-known fable among Greek sailors tells of a mermaid who asks ships, "Is King Alexander alive?" The correct answer, "He is alive and well and rules the world!" makes the sea calm. Any other answer turns the mermaid into a raging monster.

In ancient Persian literature, Alexander was sometimes seen as a destroyer. But in later Islamic Persia, influenced by the Alexander Romance, he was portrayed more positively. Firdausi's Shahnameh ("The Book of Kings") includes Alexander as a mythical figure who explored the world in search of the Fountain of Youth. In the Shahnameh, Alexander's first journey is to Mecca to pray at the Kaaba.

The figure of Dhu al-Qarnayn ("The Two-Horned One") in the Qur'an is believed by many scholars to refer to Alexander. In this tradition, he was a heroic figure who built a great wall to defend against dangerous nations. He also traveled the known world looking for the Water of Life and Immortality.

In Hindi and Urdu, the name "Sikandar" (from the Persian name for Alexander) means a rising young talent. The Delhi Sultanate ruler Alauddin Khalji even called himself "Sikandar-i-Sani" (the Second Alexander the Great). In medieval Europe, Alexander was honored as one of the Nine Worthies, a group of heroes who showed ideal qualities of chivalry.

Alexander the Great Quotes

- "Remember upon the conduct of each depends the fate of all."

- "I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion."

- "There is nothing impossible to him who will try."

- "Whatever possession we gain by our sword cannot be sure or lasting, but the love gained by kindness and moderation is certain and durable."

- "My treasure lies in my friends."

- "I would rather live a short life of glory than a long one of obscurity."

Cool Facts About Alexander the Great

- Alexander’s empire stretched from Greece to Egypt in the south. It went as far as modern-day Pakistan in the east.

- In many of his most important and decisive victories, Alexander's army was much smaller than his enemy's.

- When Alexander was ten, his father was offered a horse that no one could tame. Alexander noticed the horse was afraid of its own shadow. He asked to try and managed to calm the horse. Philip was so proud that he bought the horse for Alexander. Alexander named it Bucephalas, meaning "ox-head." Bucephalas carried Alexander on many of his campaigns, even to India. When the horse died at age 30, Alexander named a city after him, Bucephala.

- Alexander carried an annotated copy of the Iliad with him on his campaigns.

- After defeating Darius, he tried to introduce proskynesis, a gesture of bowing or kissing the hand that Persians showed to their superiors. This made many of his Macedonian soldiers unhappy, and Alexander eventually stopped requiring it.

- In India, Alexander suffered a serious injury when an arrow pierced his armor and entered his lung.

- Cleitus the Black saved Alexander's life. He cut off a Persian soldier’s arm just before the Persian could kill Alexander with his scimitar.

Images for kids

-

A Hellenistic bust of a young Alexander the Great, possibly from Ptolemaic Egypt, 2nd-1st century BC, now in the British Museum

-

Porus surrenders to Alexander

-

Alexander (left) and Hephaestion (right): Both were connected by a tight man-to-man friendship

-

A coin of Alexander the Great struck by Balakros or his successor Menes, both former somatophylakes (bodyguards) of Alexander, when they held the position of satrap of Cilicia in the lifetime of Alexander, c. 333-327 BC. The obverse shows Heracles, ancestor of the Macedonian royal line and the reverse shows a seated Zeus Aëtophoros.

-

Alexander portrayal by Lysippos

-

A fresco depicting a hunt scene at the tomb of Philip II, Alexander's father, at the Archaeological Site of Aigai, the only known depiction of Alexander made during his lifetime, 330s BC

-

A Roman copy of an original 3rd century BC Greek bust depicting Alexander the Great, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

-

Dedication of Alexander the Great to Athena Polias at Priene, now housed in the British Museum

-

This medallion was produced in Imperial Rome, demonstrating the influence of Alexander's memory. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

See also

In Spanish: Alejandro Magno para niños

In Spanish: Alejandro Magno para niños