Amundsen's South Pole expedition facts for kids

Amundsen, Hanssen, Hassel, and Wisting at Polheim at the South Pole

|

|

| Leader | Roald Amundsen |

|---|---|

| Start | Framheim, Great Ice Barrier 19 October 1911 |

| End | Geographic South Pole 14 December 1911 |

| Ships | Fram |

| Crew |

|

| Achievements |

|

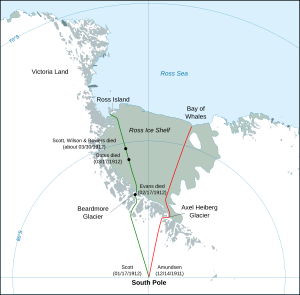

| Route | |

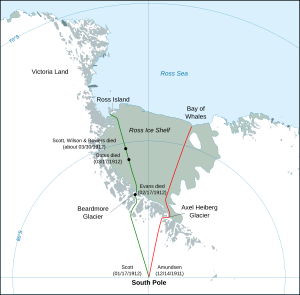

Amundsen's route compared to Scott's |

|

The first expedition to reach the Geographic South Pole was led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. He and four teammates arrived at the pole on December 14, 1911. This was five weeks before a British team led by Robert Falcon Scott. Amundsen and his team returned safely to their base. Later, they learned that Scott and his four companions had died on their way back.

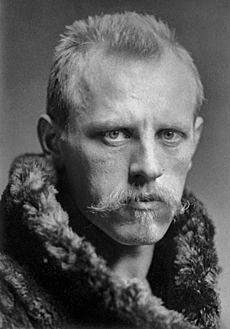

Amundsen first planned to explore the Arctic and reach the North Pole. He wanted to drift in an ice-stuck ship. He got to use Fridtjof Nansen's famous ship, Fram. He also raised a lot of money for his trip. But in 1909, two American explorers, Frederick Cook and Robert Peary, both said they had reached the North Pole.

Amundsen then secretly changed his goal. He decided to go for the South Pole instead. He wasn't sure if people would still support him. When he left in June 1910, even his crew thought they were going to the Arctic. He only told them their real destination was Antarctica when Fram left their last stop in Madeira.

Amundsen set up his Antarctic base, called "Framheim," in the Bay of Whales. This bay is on the Great Ice Barrier. After many months of getting ready and setting up supply points, his team started for the pole in October 1911. On their journey, they found the Axel Heiberg Glacier. This glacier gave them a path to the polar plateau and then to the South Pole.

The team was very good at using skis and sled dogs. This made their journey fast and mostly smooth. The expedition also explored King Edward VII Land for the first time. They also did a lot of research on the ocean.

Many people praised the expedition's success. However, in the United Kingdom, the sad story of Scott's failure often overshadowed Amundsen's win. Some people criticized Amundsen for keeping his plans secret until the very end. Today, experts on polar history recognize the great skill and bravery of Amundsen's team. The permanent science base at the South Pole is named the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, honoring both explorers.

Contents

Roald Amundsen's Early Life and Polar Dreams

Roald Amundsen was born in Norway in 1872. His father was a ship-owner. In 1893, he stopped studying medicine to become a sailor. He sailed to the Arctic on a ship called Magdalena. After more trips, he became a second mate. When not at sea, he practiced skiing in Norway's tough Hardangervidda plateau.

In 1896, Amundsen was inspired by his countryman Fridtjof Nansen. He joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition as a mate on the ship Belgica. In early 1898, the ship got stuck in pack ice in the Bellinghausen Sea. They were stuck for almost a year. This was the first time an expedition spent a full winter in Antarctic waters. The crew faced sadness, hunger, and illness like scurvy. Amundsen stayed calm and learned a lot from this experience. He studied polar exploration methods, like what gear, clothes, and food to use.

The Belgica voyage started what is known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Many other countries soon sent expeditions. But when Amundsen returned to Norway in 1899, he looked north. He felt ready to lead his own trip. He planned to sail through the Northwest Passage. This was a sea route from the Atlantic to the Pacific through Canada's northern islands. No one had fully sailed it before.

Amundsen got his captain's license. He bought a small ship called Gjøa and made it ready for the Arctic. He got support from King Oscar of Sweden and Norway and Nansen. He also got enough money to leave in June 1903 with six crew members. The trip lasted until 1906 and was a huge success. The Northwest Passage, which had stopped sailors for centuries, was finally conquered. At 34, Amundsen became a national hero. He was one of the top polar explorers.

In November 1906, the American Robert Peary came back from trying to reach the North Pole. He claimed a new record for going the farthest north. But later historians questioned this. In July 1907, Frederick Cook, who had sailed with Amundsen on Belgica, also went north. People thought he was trying for the North Pole. A month later, Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition sailed for Antarctica. Robert Falcon Scott was also getting ready for another expedition. Amundsen didn't want the British to be the first in the south. He spoke publicly about leading an Antarctic expedition, even though he still preferred the North Pole.

Planning the Expedition

Getting the Ship Fram

In 1893, Nansen had sailed his ship Fram into the Arctic ice. He let it drift towards Greenland, hoping it would pass over the North Pole. It didn't reach the pole, and Nansen's attempt to walk there also failed. But Nansen's idea became the basis for Amundsen's Arctic plans. Amundsen thought if he entered the Arctic Ocean from the Bering Strait, his ship would drift closer to the pole.

Amundsen asked Nansen for advice. Nansen said Fram was the only ship good enough for such a trip. Fram was built in 1891–93 by Colin Archer, a top Norwegian shipbuilder. It was designed to handle the toughest Arctic conditions. The ship had a round hull, which Nansen said helped it "slip like an eel" out of the ice. Its hull was covered in very hard wood for extra strength. The ship was wide compared to its length. This made it strong in ice but slow in open water. However, its main purpose was to be a safe and warm home for the crew for many years.

Fram was almost unharmed after Nansen's expedition, spending nearly three years in the polar ice. After that, it was used by Otto Sverdrup for four years. He explored and mapped a huge area in the northern Canadian islands. After Sverdrup's trip ended in 1902, Fram was stored in Christiania. The ship belonged to the state, but Nansen usually had first choice to use it. In September 1907, Amundsen was told he could have the ship.

First Steps and Funding

Amundsen announced his plans on November 10, 1908. He spoke at a meeting of the Norwegian Geographical Society. He said he would take Fram around Cape Horn to the Pacific Ocean. After getting supplies in San Francisco, the ship would go north through the Bering Strait to Point Barrow. From there, he would sail into the ice and let the ship drift for four or five years. Science would be as important as exploring new places. Amundsen hoped their observations would solve many mysteries.

People were very excited about the plan. The next day, King Haakon gave 20,000 kroner to start the fundraising. On February 6, 1909, the Norwegian Parliament approved 75,000 kroner to fix up the ship. Amundsen's brother, Leon, handled the fundraising and business side. This allowed Amundsen to focus on planning the trip.

In March 1909, news came that Shackleton had gotten very close to the South Pole. He was only 97 nmi away before turning back. Amundsen noted that "a little corner remained" in the south. He praised Shackleton's achievement. After this near miss, Scott quickly said he would lead an expedition to reach that "little corner" and claim the pole for the British Empire.

Choosing the Team

Amundsen picked three naval officers for his team. Thorvald Nilsen was a navigator and second-in-command. Hjalmar Fredrik Gjertsen was made the expedition doctor, even without much medical training. He quickly learned about surgery and dentistry. A naval gunner, Oscar Wisting, was chosen because he was good at many tasks. Amundsen said Wisting became very good with sled dogs.

Olav Bjaaland, a champion skier, was an early choice. He was also a skilled carpenter and ski-maker. Bjaaland came from a region in Norway known for its great skiers. Amundsen believed that skis and sled dogs were the best way to travel in the Arctic. He wanted the best dog drivers. Helmer Hanssen, who had been with Amundsen on the Gjøa trip, agreed to join again. Later, Sverre Hassel, a dog expert, also joined. He had been on Sverdrup's Fram voyage. The carpenter Jørgen Stubberud built a portable base hut for the expedition. He also asked to join the trip, and Amundsen agreed. Amundsen knew a good cook was important. He hired Adolf Lindstrøm, another veteran from Sverdrup's trip, who had cooked on Gjøa.

Amundsen had learned from his past trips that stable and friendly companions were key for long voyages. With these experienced people, he felt he had a strong core team. He kept hiring through 1909. The Fram team would eventually have 19 members. All but one were Amundsen's personal choices. The exception was Hjalmar Johansen, who Nansen asked Amundsen to take. Johansen had struggled after his famous march with Nansen. Nansen wanted to give him another chance. Amundsen reluctantly agreed. The team also had two foreigners: a Russian oceanographer, Alexander Kuchin, and a Swedish engineer, Knut Sundbeck.

A Secret Change of Plans

In September 1909, newspapers reported that Cook and Peary each claimed to have reached the North Pole. Cook said he did it in April 1908, and Peary a year later. Amundsen didn't pick a side in the debate. But he knew his own plans would be greatly affected. Without the North Pole as a goal, he would struggle to get public interest or money. He thought, "If the expedition was to be saved... there was nothing left for me but to try and solve the last great problem—the South Pole." So, Amundsen decided to go south. The Arctic trip could wait "for a year or two."

Amundsen did not tell anyone about his new plan. The money he had raised was for Arctic science. There was no guarantee his supporters would agree to this big change. Also, Nansen might take back Fram, or the government might stop the trip. This could upset Scott and the British. Amundsen kept his intentions secret from everyone except his brother Leon and his second-in-command, Nilsen. This secrecy caused some problems. Scott had sent Amundsen instruments so their two expeditions could take comparative readings. When Scott called Amundsen to talk about working together, Amundsen refused the call.

The new secret plan was for Fram to leave Norway in August 1910. It would sail to Madeira in the Atlantic, its only stop. From there, the ship would go straight to the Ross Sea in Antarctica. Amundsen planned to set up his base camp in the Bay of Whales. This was the farthest south a ship could go in the Ross Sea. It was 60 nmi closer to the Pole than Scott's planned base. Shackleton had thought the ice in the Bay of Whales was unstable. But Amundsen studied Shackleton's notes. He decided the ice there was stable enough for a safe base. After dropping off the shore party, Fram would do ocean research in the Atlantic. Then it would pick up the shore party in early 1912.

Gear and Supplies

Amundsen didn't understand why British explorers avoided dogs. He later wrote, "Can it be that the dog has not understood its master? Or is it the master who has not understood the dog?" After deciding to go south, he ordered 100 top-quality Greenland sledge dogs.

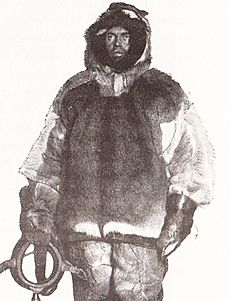

The team's ski boots were specially designed by Amundsen. He spent two years testing and changing them to make them perfect. Their polar clothes included suits of sealskin and traditional Inuit garments made from reindeer skins, wolf skin, and special fabrics. The sledges were made from Norwegian ash with steel-covered runners from American hickory. Skis, also made from hickory, were extra long to avoid falling into deep cracks in the ice. The tents were "the strongest and most practical" ever used. They had built-in floors and needed only one pole. For cooking, Amundsen chose the Swedish Primus stove. He felt Nansen's special cooker took up too much space.

Amundsen knew about the dangers of scurvy from his Belgica trip. At the time, people didn't know it was caused by a lack of vitamin C. But they knew eating fresh raw meat could prevent it. To avoid scurvy, Amundsen planned to add seal meat to their rations. He also ordered a special kind of pemmican with vegetables and oatmeal. He called it "a more stimulating, nourishing and appetising food." The expedition also had plenty of wines and spirits for medicine and special events. Amundsen remembered the low spirits on Belgica. So, he brought a library of about 3,000 books, a record player, many records, and musical instruments for leisure time.

Setting Sail

In the months before leaving, it became harder to get money for the expedition. Public interest was low, newspaper deals were canceled, and the government refused more money. Amundsen mortgaged his house to keep the expedition going. He was deeply in debt. He now depended completely on the expedition's success to avoid financial ruin.

After a month-long test trip in the northern Atlantic, Fram sailed to Kristiansand in late July 1910. There, they loaded the dogs and made final preparations. In Kristiansand, Amundsen got help from Peter "Don Pedro" Christophersen. He was a Norwegian living abroad whose brother was Norway's Minister in Buenos Aires. Christophersen offered to provide fuel and supplies to Fram in South America. Amundsen gladly accepted. Just before Fram sailed on August 9, Amundsen told his two junior officers, Prestrud and Gjertsen, the expedition's real destination. During the four-week trip to Funchal in Madeira, the crew felt uncertain. They didn't understand some of the preparations, and their questions got vague answers. Amundsen's biographer, Roland Huntford, said this was "enough to generate suspicion and low spirits."

Fram reached Funchal on September 6. Three days later, Amundsen told the crew the new plan. He said he planned "a detour" to the South Pole before going to the North Pole. He asked each man if he was willing to go, and everyone said yes. Amundsen wrote a long letter to Nansen. He explained how Cook's and Peary's claims had ruined his original plans. He felt forced to do this and asked for forgiveness. He hoped his success would make up for any offense.

Before leaving Funchal on September 9, Amundsen sent a telegram to Scott. He told him about the change of plans. Scott's ship Terra Nova had left Cardiff on June 15 and was due in Australia in early October. Amundsen sent his telegram to Melbourne. It simply said he was going south. It didn't give any details about his plans or destination in Antarctica. Scott wrote to the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) secretary, John Scott Keltie, "We shall know in due course I suppose."

News of Amundsen's new plans reached Norway in early October. It caused a mostly negative reaction. Nansen gave his blessing, but most of the press and public condemned Amundsen's actions. Funding almost completely stopped. Reactions in Britain were also negative. An initial disbelief soon turned to anger. Sir Clements Markham, an important former RGS president, wrote, "I have sent full details of Amundsen's underhand conduct to Scott... If I was Scott I would not let them land." Unaware of these reactions, Fram sailed south for four months. The first icebergs were seen on New Year's Day 1911. The Barrier itself appeared on January 11. On January 14, Fram was in the Bay of Whales.

First Season: Setting Up Base (1910–11)

Building Framheim

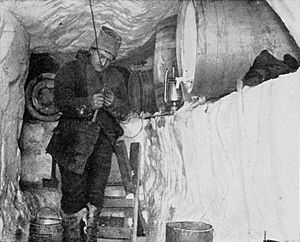

After Fram was anchored to the ice in the Bay of Whales, Amundsen chose a spot for the main hut. It was about 2.2 nmi from the ship. Six dog teams moved supplies to the site. Work on building the hut began. Bjaaland and Stubberud dug deep foundations into the ice and leveled the ground. The hut was built facing east–west, with the door facing west. This way, the wind only hit the shorter eastern wall. The roof was on by January 21, and the hut was finished six days later. By then, a large amount of meat, including 200 seals, had been brought to the base. This was for the shore party and for supply depots. The base was named Framheim, meaning "the home of Fram."

Early on February 3, Terra Nova arrived unexpectedly in the Bay of Whales. It had sailed from New Zealand and arrived in McMurdo Sound in early January. After dropping off Scott and his main team, Terra Nova took a group of six men, led by Victor Campbell, east to King Edward VII Land. This group wanted to explore this unknown area. But sea ice stopped them from getting to shore. The ship was sailing west along the Barrier edge, looking for a landing spot, when it found Fram. Scott had thought Amundsen might set up base in the Weddell Sea, on the other side of the continent. This showed that the Norwegians had a 60-nautical-mile head start in the race for the pole. This was alarming for the British.

The two groups were polite to each other. Campbell and his officers had breakfast on Fram and then hosted lunch on Terra Nova. Amundsen was relieved to learn that Terra Nova had no radio. This meant his plan to be first with the news of a polar victory was safe. However, he was worried by Campbell's comment that Scott's motorized sledges were working well. Still, Amundsen offered the British team a spot near Framheim for their King Edward VII Land exploration. Campbell declined and sailed to McMurdo Sound to tell Scott where Amundsen was.

Setting Up Supply Depots

In early February, Amundsen started organizing trips to lay supply depots across the Barrier. These were for the polar journey the following summer. Supply depots placed ahead of time would mean the South Pole team wouldn't have to carry as much food and fuel. These trips would also test the equipment, dogs, and men. For the first trip, starting February 10, Amundsen chose Prestrud, Helmer Hanssen, and Johansen to go with him. They would use 18 dogs to pull three sledges. Before leaving, Amundsen gave Nilsen instructions for Fram. The ship was to sail to Buenos Aires for supplies. Then it would do ocean research in the Southern Ocean. After that, it would return to the Barrier as early as possible in 1912.

When the four men started their journey south, they only knew about the Barrier from books by earlier explorers. They expected tough travel. They were surprised to find the Barrier surface was like a regular glacier. They covered 15 nmi on the first day. Amundsen noted how well his dogs were doing. He wondered why the English didn't like using dogs on the Barrier. The team reached 80° S on February 14. After setting up the depot, they turned for home. They reached Framheim on February 16.

The second depot-laying team left Framheim on February 22. There were eight men, seven sledges, and forty-two dogs. Conditions on the Barrier had gotten much worse. Temperatures had dropped by 9 °C (16 °F), and rough snow covered the smooth ice. In temperatures sometimes as low as -40 °C (-40 °F), the team reached 81° S on March 3. There, they set up a second depot. Amundsen, Helmer Hanssen, Prestrud, Johansen, and Wisting then continued with the strongest dogs. They hoped to reach 83° S. But in difficult conditions, they stopped at 82° S on March 8. Amundsen saw that the dogs were tired. The team turned for home. With lighter sledges, they traveled fast and reached Framheim on March 22.

Amundsen wanted more supplies taken south before the polar night made travel impossible. On March 31, a team of seven men led by Johansen left Framheim for the 80° S depot. They carried six slaughtered seals, which was 2,400 lb of meat. The team returned on April 11, three days later than expected. They had gotten lost in an area with many deep cracks in the ice.

Overall, the depot trips set up three depots. They contained 7,500 lb of supplies. This included 3,000 lb of seal meat and 40 impgal of paraffin oil. Amundsen learned a lot from these trips. Especially on the second one, the dogs struggled with sledges that were too heavy. He decided to use more dogs for the polar journey, even if it meant fewer men. The trips also showed some disagreements among the men, especially between Johansen and Amundsen. During the second depot trip, Johansen openly complained about the equipment. Amundsen felt his authority was challenged.

Winter at Framheim

The sun set over Framheim on April 21. It would not appear again for four months. Amundsen remembered how boredom and low spirits had affected the Belgica expedition during winter. Even though they couldn't sledge, he made sure the shore party stayed busy. One urgent task was to improve the sledges. They hadn't worked well during the depot trips. Amundsen had brought some sledges from Sverdrup's 1898–1902 Fram expedition. He now thought these would be better. Bjaaland made these older sledges almost a third lighter by shaving down the wood. He also built three new sledges from extra hickory wood. The adapted sledges would be used to cross the Barrier. Bjaaland's new ones would be for the final part of the journey across the polar plateau.

Johansen prepared the sledging food. This included 42,000 biscuits, 1,320 tins of pemmican, and about 220 lb of chocolate. Other men worked on improving boots, cooking gear, goggles, skis, and tents. To fight scurvy, the men ate seal meat twice a day. This meat had been collected and frozen before winter. The cook, Lindstrøm, added vitamin C with bottled cloudberries and blueberries. He also made wholemeal bread with fresh yeast, which is rich in B vitamins.

Amundsen trusted his men and equipment. But Hassel noted that Amundsen was worried about Scott's motor sledges. He feared they would help the British win. Because of this, Amundsen planned to start the polar journey as soon as the sun rose in late August. Johansen warned that it would be too cold on the Barrier so early. Amundsen ignored him. When the sun rose on August 24, seven sledges were ready. Johansen's worries seemed right. Harsh conditions for the next two weeks, with temperatures as low as -58 °C (-72 °F), stopped them from leaving. On September 8, 1911, when the temperature rose to -27 °C (-17 °F), Amundsen decided he couldn't wait. The party of eight set off. Lindstrøm stayed alone at Framheim.

Second Season: The South Pole Journey (1911–12)

A Difficult Start

The team made good progress at first, traveling about 15 nmi each day. The dogs ran so hard that some from the strongest teams were unhooked and placed on the sledges as extra weight. The men wore wolf-skin and reindeer-skin clothes. They could handle the freezing temperatures while moving. But when they stopped, they suffered and barely slept. The dogs' paws got frostbitten. On September 12, with temperatures down to -56 °C (-69 °F), the team stopped after only 4 nmi. They built igloos for shelter. Amundsen now realized they had started the march too early. He decided they should return to Framheim. He would not risk lives for stubbornness. Johansen wrote in his diary about the foolishness of starting such a long trip too early. He also wrote about the dangers of being obsessed with beating the English.

On September 14, on their way back to Framheim, they left most of their gear at the 80° S depot. This made the sledges lighter. The next day, in freezing temperatures with a strong headwind, several dogs froze to death. Others were too weak and were put on the sledges. On September 16, 40 nmi from Framheim, Amundsen told his men to go home as fast as possible. He didn't have his own sledge. He jumped onto Wisting's, and with Helmer Hanssen and his team, raced ahead. They left the others behind. The three arrived back at Framheim after nine hours. Stubberud and Bjaaland followed two hours later, and Hassel shortly after. Johansen and Prestrud were still out on the ice, without food or fuel. Prestrud's dogs had failed, and his heels were badly frostbitten. They reached Framheim after midnight, more than seventeen hours after they had turned for home.

The next day, Amundsen asked Johansen why he and Prestrud were so late. Johansen angrily said he felt they had been abandoned. He criticized Amundsen for leaving his men behind. Amundsen later told Nansen that Johansen had been "violently insubordinate." Because of this, Johansen was not allowed to join the polar party. Amundsen reduced the polar party to five men. Johansen was placed under Prestrud's command. Prestrud was much younger as an explorer. This new group would explore King Edward VII Land. Stubberud was convinced to join them. This left Amundsen, Helmer Hanssen, Bjaaland, Hassel, and Wisting as the new South Pole team.

The Journey to the South Pole

Across the Barrier and Mountains

Amundsen was excited to start again. But he waited until mid-October for the first signs of spring. He was ready to leave on October 15, but bad weather delayed him for a few more days. On October 19, 1911, the five men, with four sledges and fifty-two dogs, began their journey. The weather quickly worsened. In thick fog, the team went into the area of deep cracks that Johansen's team had found the previous autumn. Wisting later remembered how his sledge, with Amundsen on it, almost fell into a crack when the snow bridge broke.

Despite this near accident, they covered more than 15 nmi a day. They reached their 82° S depot on November 5. They marked their route with snow cairns, built every three miles. On November 17, they reached the edge of the Barrier and faced the Transantarctic Mountains. Scott would follow the Beardmore Glacier route that Shackleton had found. But Amundsen had to find his own way through the mountains. After exploring the foothills for several days and climbing to about 1,500 ft, the team found what looked like a clear path. It was a steep glacier 30 nmi long leading up to the plateau. Amundsen named this the Axel Heiberg Glacier, after one of his main financial supporters. It was a harder climb than they expected. They had to take many detours, and the snow was deep and soft. After three days of tough climbing, the team reached the glacier summit. Amundsen praised his dogs. He dismissed the idea that they couldn't work in such conditions. On November 21, the team traveled 17 miles (27 km) and climbed 5,000 ft.

The Final Push to the Pole

When they reached 10,600 ft at the top of the glacier, at 85° 36′ S, Amundsen got ready for the last part of the journey. Of the 45 dogs that had made the climb (7 had died during the Barrier stage), only 18 would continue.

The team loaded three sledges with supplies for a march of up to 60 days. They left the rest of the supplies in a depot. Bad weather stopped them until November 25. Then, they set off carefully over the unknown ground in constant fog. They were traveling over an icy surface with many cracks. This, along with poor visibility, slowed them down. Amundsen called this area the "Devil's Glacier." On December 4, they came to an area where cracks were hidden under layers of snow and ice. This made a "hollow" sound when they passed over it. Amundsen named this area "The Devil's Ballroom." Later that day, they reached more solid ground at 87° S.

On December 8, the Norwegians passed Shackleton's record of 88° 23′ S. As they got closer to the pole, they looked for any sign that another expedition had gotten there first. While camped on December 12, they were briefly scared by a black object on the horizon. But it turned out to be their own dogs' droppings in the distance, made bigger by a mirage. The next day, they camped at 89° 45′ S, 15 nmi from the pole. On December 14, 1911, with his teammates' agreement, Amundsen walked in front of the sledges. Around 3 pm, the team reached the area of the South Pole. They planted the Norwegian flag and named the polar plateau "King Haakon VII's Plateau." Amundsen later thought about the irony of his achievement: "Never has a man achieved a goal so completely opposite to his wishes. The area around the North Pole—devil take it—had fascinated me since childhood, and now here I was at the South Pole. Could anything be more crazy?"

For the next three days, the men worked to find the exact position of the pole. After the confusing claims of Cook and Peary in the north, Amundsen wanted to leave clear markers for Scott. After taking several sextant readings at different times, Bjaaland, Wisting, and Hassel skied out in different directions to "box" the pole. Amundsen believed that between them, they would find the exact point. Finally, the team set up a tent, which they called Polheim. It was as close as they could get to the actual pole based on their observations. In the tent, Amundsen left equipment for Scott and a letter for King Haakon. He asked Scott to deliver it.

The Return Journey

On December 18, the team started their journey back to Framheim. Amundsen was determined to return to civilization before Scott. He wanted to be the first to share the news. Still, he limited their daily distances to 15 nmi. This was to save the strength of the dogs and men. In the 24-hour daylight, the team traveled during the "night" hours. This kept the sun at their backs and reduced the risk of snow-blindness. Guided by the snow cairns they built on their way out, they reached the Butchers' Shop on January 4, 1912. They then began the descent to the Barrier. The men on skis "went whizzing down." But for the sledge drivers, Helmer Hanssen and Wisting, the descent was dangerous. The sledges were hard to control. They added brakes to the runners to allow quick stops when they met cracks in the ice.

On January 7, the team reached their first depot on the Barrier. Amundsen now felt they could go faster. The men adopted a routine of traveling 15 nmi, stopping for six hours, then continuing. With this plan, they covered about 30 nmi a day. On January 25, at 4 am, they reached Framheim. Of the 52 dogs that started in October, 11 had survived, pulling 2 sledges. The journey to the pole and back had taken 99 days. This was 10 days fewer than planned. They had covered about 1,860 nmi.

Telling the World

When he returned to Framheim, Amundsen quickly ended the expedition. After a farewell dinner, the team loaded the surviving dogs and valuable equipment onto Fram. The ship left the Bay of Whales late on January 30, 1912. Their destination was Hobart in Tasmania. During the five-week voyage, Amundsen prepared his telegrams and wrote his first report for the press. On March 7, Fram reached Hobart. Amundsen quickly learned there was no news from Scott yet. He immediately sent telegrams to his brother Leon, to Nansen, and to King Haakon. He briefly told them of his success. The next day, he sent the first full story to London's Daily Chronicle, to whom he had sold exclusive rights. Fram stayed in Hobart for two weeks. While there, Douglas Mawson's ship Aurora, which was on the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, joined them. Amundsen gave them his 11 surviving dogs as a gift.

Other Expedition Achievements

Eastern Party Exploration

On November 8, 1911, Prestrud, Stubberud, and Johansen left for King Edward VII Land. It was hard to find where the solid ice of the Barrier met the land. On December 1, the team saw what was clearly dry land for the first time. It was a nunatak that Scott had recorded during the Discovery expedition in 1902. After reaching this point, they collected rock samples and mosses. They briefly explored the area before returning to Framheim on December 16. They were the first people to set foot on King Edward VII Land.

Fram and the Japanese Expedition

After leaving the Bay of Whales on February 15, 1911, Fram sailed to Buenos Aires. She arrived there on April 17. Nilsen learned that the expedition's money was gone. A sum meant for the ship's needs had not appeared. Luckily, Amundsen's friend Don Pedro Christopherson was there. He kept his promise to provide supplies and fuel. Fram left in June for an ocean research trip between South America and Africa. This took three months. The ship returned to Buenos Aires in September for final repairs and supplies. Then it sailed south on October 5. Strong winds and stormy seas made the voyage longer. But the ship arrived at the Bay of Whales on January 9, 1912.

On January 17, the men in Framheim were surprised by another ship. It was the Kainan Maru, carrying the Japanese Antarctic Expedition led by Nobu Shirase. Communication between the two teams was difficult because of language differences. But the Norwegians understood that the Japanese were heading for King Edward VII Land. Kainan Maru left the next day. On January 26, she landed a team on King Edward VII Land. This was the first landing on this shore from the sea. Earlier attempts by Discovery (1902), Nimrod (1908), and Terra Nova (1911) had all failed.

What Happened Next

Public Reactions

In Hobart, Amundsen received congratulatory messages. These came from people like former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt and King George V of the United Kingdom. The King was especially pleased that Amundsen's first stop back was on British land. In Norway, which had only become an independent country six years earlier, the news was celebrated with big headlines. The national flag was flown everywhere. All who took part in the expedition received the Norwegian South Pole medal.

However, Amundsen's biographer, Roland Huntford, noted "the chill underneath the cheers." Some people still felt uneasy about Amundsen's methods. One Norwegian newspaper was relieved that Amundsen found a new route. This meant he didn't interfere with Scott's path from McMurdo Sound.

In Britain, the press reaction to Amundsen's victory was calm but generally positive. Besides the excited reports in the Daily Chronicle and the Illustrated London News, the Manchester Guardian said that any reason for blame was erased by the Norwegians' courage. Readers of Young England were told not to begrudge "the brave Norseman" the honor he had earned. The Boy's Own Paper suggested every British boy should read Amundsen's expedition story. The Times offered a mild criticism of Amundsen. They said he should have told Scott sooner. "No one would have welcomed co-operation... more than Captain Scott," they wrote. "Still, no one who knows Captain Amundsen can have any doubt of his integrity, and since he states he has reached the Pole we are bound to believe him."

Senior figures at the RGS expressed more negative feelings, at least privately. To them, Amundsen's achievement was the result of "a dirty trick." Markham hinted that Amundsen's claim might be fake. "We must wait for the truth until the return of the Terra Nova," he said. Later in 1912, when Amundsen spoke at the RGS, he felt disrespected. Lord Curzon, the Society's president, jokingly called for "three cheers for the dogs." Shackleton did not criticize Amundsen's victory. He called him "perhaps the greatest polar explorer of today." Before she heard about her husband's death, Kathleen Scott admitted that Amundsen's journey "was a very fine feat... in spite of one's irritation one has to admire it."

The Scott Tragedy

Amundsen left Hobart to give lectures in Australia and New Zealand. He then went to Buenos Aires, where he finished writing his expedition story. Back in Norway, he oversaw the book's publication. Then he visited Britain before starting a long lecture tour in the United States. In February 1913, while in Madison, Wisconsin, he heard the news. Scott and four teammates had reached the pole on January 17, 1912. But they had all died by March 29 during their return journey. The bodies of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers were found in November 1912, after the Antarctic winter ended. Amundsen's first reaction was, "Horrible, horrible." His more formal tribute followed: "Captain Scott left a record, for honesty, for sincerity, for bravery, for everything that makes a man."

According to Huntford, the news of Scott's death meant that "Amundsen the victor was eclipsed... by Scott the martyr." In the United Kingdom, a story quickly grew. Scott was shown as a noble hero who played fairly. He was defeated because Amundsen was just seeking glory. Amundsen had hidden his true plans and used dogs instead of relying on honest man-hauling. Also, he was seen as a "professional." In the mindset of upper-class Britain at that time, this lessened anything he achieved. This story was strongly supported when Scott's journals and his "Message to the Public" were published. Huntford points out that "[Scott's] literary talent was his trump. It was as if he had reached out from his buried tent and taken revenge." Even so, among explorers, Amundsen's name continued to be respected. In his account of the Terra Nova expedition, Scott's comrade Apsley Cherry-Garrard wrote that Amundsen's success was mainly due to "the very remarkable qualities of the man." He specifically mentioned Amundsen's courage in choosing to find a new route instead of following the known path.

Modern Discoveries

One hundred years after Amundsen's expedition, researchers made a claim. They said that the tent and flags are now buried under 17 m (56 ft) of ice. They are also about one nautical mile north of the South Pole.

See Also

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- Comparison of the Amundsen and Scott Expeditions

Images for kids

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |