Arkansas in the American Civil War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Arkansas |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Capital | 1861–1863 Little Rock 1863–1865 Washington |

||

| Largest City | Little Rock | ||

| Admission to confederacy | May 18, 1861 (9th) | ||

| Population |

|

||

| Forces supplied |

|

||

| Major garrisons/armories | Fort Smith Little Rock Arsenal |

||

| Governor | 1861–1862 Henry M. Rector 1862 Thomas Fletcher (acting) 1862–1865 Harris Flanagin |

||

| Senators |

|

||

| Representatives | List | ||

| Restored to the Union | June 22, 1868 | ||

During the American Civil War, Arkansas was a Confederate state. However, it first voted to stay in the Union. After the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln asked states for soldiers to stop the rebellion. Arkansas and several other states then decided to leave the Union. For the rest of the war, Arkansas was important for controlling the Mississippi River, a key waterway.

Arkansas provided many soldiers for the Confederacy. This included 48 infantry regiments, 20 artillery groups, and over 20 cavalry regiments. Most of these soldiers fought in the Western part of the war. However, the Third Arkansas fought bravely in the Army of Northern Virginia in the East. Major-General Patrick Cleburne was Arkansas's most famous military leader. The state also supplied soldiers for the Union side. This included four infantry regiments, four cavalry regiments, and one artillery group of white soldiers. It also had six infantry regiments and one artillery group of "U.S. Colored Troops" (African American soldiers).

Many small fights and big battles happened in Arkansas. One important battle was the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern in March 1862. This battle was a major win for the Union in the Trans-Mississippi area. It helped the Union control northern Arkansas. The state capital, Little Rock, was captured by Union forces in 1863. By the end of the war, people in Arkansas were tired of the Confederate cause. This was due to things like the draft (forcing people to join the army), high taxes, and strict military rule. Arkansas officially rejoined the Union in 1868.

Contents

Arkansas Before the War

Arkansas joined the United States on June 15, 1836. It became the 25th state and allowed slavery. Much of Arkansas before the war was wild and had few people. Slavery had been in the area since French and Spanish colonial times. But it grew much larger after Arkansas became a state. Large farms, called plantations, grew in areas with easy access to rivers. These rivers helped move crops like cotton to market. Counties along the Mississippi, Arkansas, White, Saline, and Ouachita rivers had the most enslaved people. Slavery existed in the mountainous parts of the state too, but on a smaller scale. The 1850s were a time of fast economic growth for Arkansas.

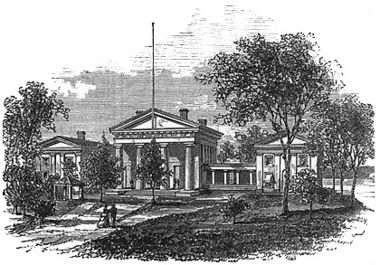

News of John Brown's Raid in Virginia in 1859 made people more interested in the state's militia system. A militia is like a state army. Arkansas had an organized militia before the Civil War. State law said that most men of a certain age had to serve in the military. By August 1860, the state's militia had 62 regiments. Many counties also had volunteer companies. These groups trained more often and had better equipment. They were important in taking over federal buildings like the Little Rock Arsenal and Fort Smith. This happened in February 1861, before Arkansas officially left the Union.

In the 1860 Presidential Election, Abraham Lincoln was not even on the ballot in Arkansas. The state voted for Southern Democratic Party candidate John C. Breckinridge.

The Secession Crisis Begins

Abraham Lincoln winning the presidential election of 1860 caused South Carolina to leave the Union. By February 1861, six more Southern states also left. These seven states formed a temporary government and chose Montgomery, Alabama as their capital. A meeting in Washington in February tried to solve the problem, but it failed.

As more states left, people in Arkansas became very worried. In January 1861, the General Assembly asked people to vote. They wanted to know if Arkansas should hold a meeting to consider leaving the Union. People also voted for delegates to this meeting. On February 18, 1861, Arkansans voted to hold a secession meeting. But they mostly elected delegates who wanted to stay in the Union.

Governor Rector and the Arsenal

People who wanted to leave the Union started asking to take over the Federal Arsenal in Little Rock. Rumors spread that the U.S. government would send more troops to the Arsenal. So, important citizens from Helena sent a message to Governor Henry M. Rector. They offered 500 men to help take the Arsenal. Governor Rector told them he could not order them to take a federal post. But he said if people gathered to defend themselves, he would support them.

Because of the Governor's message, militia groups started gathering in Little Rock by February 5, 1861. They told the Arsenal commander, Captain James Totten, they planned to take it. More than a thousand militiamen gathered. The Little Rock City Council worried about a battle in the city. They asked the Governor to take control of the militia and seize the Arsenal to avoid bloodshed.

Governor Rector then took charge. With militia forces surrounding the Arsenal, he demanded its surrender. Captain Totten agreed to leave the Arsenal if his troops could safely leave the state. Governor Rector agreed, and the militia took control of the Arsenal on February 8, 1861. Later, cannons were set up at Helena on the Mississippi River and Pine Bluff on the Arkansas. This was to stop federal troops from reinforcing other posts.

Arkansas's Secession Meeting

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln became president. In his speech, he said the Constitution was a strong agreement. He said leaving the Union was "legally void." He promised not to attack Southern states or end slavery where it already existed. But he said he would use force to keep federal property. His speech ended with a plea for the country to stay united.

The next day, the Arkansas Secession Convention met in Little Rock. Judge David Walker, who did not want to leave the Union, was chosen as its president. The meeting lasted two and a half weeks. Many strong speeches were made. Governor Rector spoke, urging the spread of slavery. He said that the "extension of slavery is the vital point of the whole controversy between the North and the South." He also said, "They believe slavery a sin, we do not, and there lies the trouble."

But most delegates did not think it was time to leave the Union. The convention voted against a resolution that criticized Lincoln's speech. They also voted against a plan to leave the Union only if certain conditions were met. Most believed Arkansas should only secede if the U.S. government attacked Southern states. Hoping for peace, the delegates decided to stop the meeting. They would meet again after people voted on secession in August.

Taking Fort Smith Arsenal

Confederate President Jefferson Davis ordered troops to attack Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. On April 12, they fired on the fort, forcing the U.S. soldiers to give up. In response, President Lincoln asked states for 75,000 soldiers to stop the rebellion. Even though Arkansas had not officially left the Union, Governor Rector felt this would make people want to secede. He quickly formed a militia group led by Solon Borland. This militia was sent to take the Federal Arsenal at Fort Smith on April 23, 1861. Governor Rector told President Lincoln: "The people of this Commonwealth are freemen, not slaves, and will defend to the last extremity their honor, lives, and property, against Northern mendacity and usurpation."

The Decision to Secede

The first Arkansas secession meeting had promised to "Resist to the last extremity any attempt on the part of such power (President Lincoln) to coerce any state that had succeeded from the old Union." Now, with Lincoln asking for troops, the meeting gathered again in Little Rock. On May 6, 1861, they voted to leave the Union. The vote was 69 to 1. Future Governor Isaac Murphy was the only one who voted "No." The convention explained why Arkansas was leaving. They said the main reason was the "hostility to the institution of African slavery" from the free states.

Getting Ready for War

The Secession Convention continued to meet. They started writing a new state constitution and organizing the state's military. Many at the meeting were upset with Governor Rector. They felt he used the militia to push the state closer to war by taking federal buildings. So, the new constitution tried to limit the Governor's power. His term was shortened from four years to two. Also, military matters were put under a three-person board led by the Governor. This Military Board was to create a state army, arm and feed soldiers, and call out forces to defend the state.

The convention also decided to create an "Army of Arkansas." This army would have two parts: the 1st Division in the west and the 2nd Division in the east. Each part would be led by a brigadier general. The convention chose three leaders for the new army: Major General James Yell (overall commander), Nicholas B. Pearce (commander of the First Division), and Thomas H. Bradley (commander of the Second Division).

On May 30, 1861, the convention also ordered all counties to form "home guard of minute men." These groups were for local defense until regular soldiers could be trained. Home Guard units were made of older men and boys who couldn't join the regular army. They were organized by county, with companies from each town.

Confederate Units from Arkansas

Arkansas formed 48 infantry regiments, over 20 cavalry regiments, and 20 artillery batteries for the Confederate States Army. Most Arkansas troops raised before May 1862 were sent east of the Mississippi River. They became part of a division in the Army of Tennessee. Only one infantry regiment and all cavalry and artillery units spent most of the war in the "Western Theater." This area had fewer large battles than the "Eastern Theater." After May 1862, new units raised west of the Mississippi River stayed in the Trans-Mississippi Department for the rest of the war.

One infantry regiment, the Third Arkansas, fought in the eastern part of the war for its entire duration. This made it the state's most famous Confederate military unit. It was part of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. The Third Arkansas fought in almost every major Eastern battle. These included Seven Pines, Seven Days, Harper's Ferry, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, Wilderness, and the Appomattox Campaign.

1861: Early Days of War

After Arkansas left the Union in May 1861, existing volunteer militia groups were quickly made into new infantry regiments. These were called "State Troops" and formed the Provisional Army of Arkansas. In July 1861, an agreement was made to transfer these state forces to the Confederate army. The Second Division of the Army of Arkansas was transferred. But before the First Division could transfer, it fought in the Battle of Wilson's Creek in Missouri in August 1861. Arkansas "State Troops" made up most of the forces in this battle. After the battle, these troops moved back to Arkansas. After a disagreement about joining the Confederate army, they were disbanded. Most other Confederate forces in Arkansas were sent east of the Mississippi River in late 1861. They stayed there for the rest of the war.

In November 1861, Colonel Solon S. Borland, leading Confederate forces, heard about a coming invasion of Northeast Arkansas. He asked for militia forces to help. The State Military Board allowed the Eighth Brigade of Militia to be called up. Units from several counties joined. These units formed three regiments of 30-Day Volunteers. Some of these later joined the regular Confederate army.

The Secession Convention and Military Board had worried about Arkansas troops being sent east. This quickly happened. By late September 1861, Brigadier General William J. Hardee had moved his new Arkansas troops east of the Mississippi. They joined what would become the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Arkansas soon found itself almost defenseless. Governor Rector's newspaper said: "The Confederate government has abandoned Arkansas to her fate." By November 1861, Governor Rector reported that 21 regiments had been formed, totaling 16,000 men. Another 6,000 men were expected soon.

1862: Battles and New Leaders

Many Arkansas regiments formed in summer 1861 fought under General Albert Sidney Johnston at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862. They later joined Patrick Cleburne's division of the Army of Tennessee. The remaining soldiers surrendered with that army in North Carolina at the end of the war.

In January 1862, Major General Earl Van Dorn was sent to Arkansas to build a new army. He immediately asked Governor Rector for more companies of soldiers. On January 31, 1862, Governor Rector called for 100 new companies and four artillery groups. He noted that Arkansas already had 22,000 men in the Confederate Army.

General Van Dorn led his new Army of the West into the Battle of Pea Ridge from March 6–8, 1862. This battle was a big loss for Southern forces in the Trans-Mississippi area. It led to the Union taking control of northwest Arkansas. Right after Pea Ridge, Van Dorn was ordered to move his forces east of the Mississippi River. They were to help Confederate forces near Corinth, Mississippi. Van Dorn's forces fought heavily around Corinth in the summer and fall of 1862. Brigadier General Evander McNair's Arkansas brigade eventually joined the Army of Tennessee. Its remaining soldiers surrendered with that army in North Carolina at the end of the war. Other parts of the Army of the West and several Arkansas regiments were trapped in the Siege of Vicksburg and the Siege of Port Hudson in summer 1863.

As Van Dorn left the state, Major General Samuel Curtis, who won the Battle of Pea Ridge, began invading Arkansas in early April. He moved his 17,000-man army back into Missouri for better travel routes and then headed east. He set up his supply base in Rolla, Missouri. Curtis reached West Plains, Missouri, on April 29 and turned south into Arkansas. In early May, Curtis and Steele faced many problems with supplies. Bad weather, tough land, and lack of supplies slowed them down. But by May 9, Curtis's large army reached flat ground at Searcy. It was ready to move deep into central Arkansas and take Little Rock once supplies arrived.

Major General Van Dorn left the state, but Brigadier General John S. Roane refused to go. He said Arkansas troops should stay to defend their state. Van Dorn left Roane in charge of the Arkansas military, but with almost no organized forces. Roane asked Governor Rector for help raising new troops. Rector told Roane to stop any troops passing through the state and use them for defense. General Roane immediately started building a defense against the approaching Union Army. He stopped parts of the 12th Texas Cavalry that were going east. He also ordered troops who had reached Memphis, Tennessee, to turn back. Some attempts to recruit local volunteers were made, but with little success. On May 10, Roane sent Texas cavalry as scouts to find the federal position. The scouts met many people fleeing the Union Army. They reported that Union forces were about 30,000 strong, mostly German immigrants. Roane had about 1,200 Texas horsemen to face this force. He ordered cotton stores near Searcy to be burned. Governor Rector prepared government offices for evacuation. Small Union advance groups fought with the Texas scouts between Searcy and Little Rock. On May 19, several Texas cavalry companies and a few local Arkansas companies won a small, but important, victory over General Curtis's groups at the Battle of Whitney's Lane.

On May 1, 1862, Governor Rector realized Major General Samuel Curtis's army was coming to take Little Rock. He left the city and moved the state government to Hot Springs, Arkansas. For the first three weeks of May 1862, there was no military or state government in Little Rock. Roane went to Pine Bluff and got help from Arkansas Militia Major General James Yell. They worked to recruit a new Army of the Southwest. Yell was a strong supporter of "States Defense first" and helped Roane. Senator Robert W. Johnson also helped. These three men were key to forming the new army. Meanwhile, Governor Rector sent messages to President Jefferson Davis. He threatened to leave the Confederacy unless Davis sent support. Davis sent the CSS Pontchartrain and CSS Maurepas to Little Rock. The state government did not return to Little Rock until the Pontchartrain arrived. A week later, on May 31, 1862, Major General Thomas C. Hindman arrived to take command from Roane. He ordered all troops in Pine Bluff to Little Rock.

Hindman was sent to command the Confederate Department of the Trans-Mississippi. When Hindman arrived, Union forces were still moving south from Batesville. They threatened Little Rock. Hindman found his command "bare of soldiers, penniless, defenseless, and dreadfully exposed" to the approaching Federal Army. He quickly issued strict military orders. He started conscription (forcing people to join the army), allowed guerrilla warfare, and took supplies for the state's defense. With the help of the Texas troops Roane had stopped, Hindman started spreading false information. This was to mislead Federal authorities about the strength of Arkansas's defenses. Hindman sent a combined force of Texas troops and newly formed Arkansas units to fight Curtis at the Battle of Cotton Plant on July 7, 1862. These events, along with constant harassment, confused the Federal authorities. They worried they didn't have enough supplies to conquer the state. They soon changed course from the capital and moved to Helena to get a steady supply line.

Hindman used new Confederate conscription laws to raise a new army in Arkansas in summer 1862. His methods were legally questionable. The Confederate Conscription Act of April 1862 had forbidden raising new units through conscription. The law was meant to provide replacements for existing Confederate regiments that had lost soldiers. But Hindman's problem was that General Van Dorn had taken almost every organized regiment with him to Mississippi. Hindman ignored the legal challenge and aggressively recruited. To encourage volunteers, Hindman said that volunteer companies formed before a certain date could elect their own officers. Conscript companies would have their officers appointed. Hindman had many experienced officers to help him. In early May 1862, Confederate forces in northern Mississippi reorganized. This was due to the Conscription Act. All twelve-month regiments had to re-enlist for two more years or the war's duration. A new election of officers was ordered. Men who were exempt from service could leave. Officers who did not want to run for re-election could also leave. Many senior officers from Arkansas regiments east of the Mississippi, like Colonels James Fleming Fagan, Robert G. Shaver, Simon P. Hughes, and Alexander T. Hawthorn, resigned their commands. They returned to Arkansas and helped Hindman organize new units in summer 1862.

Hindman asked for many weapons from east of the Mississippi River. Many weapons were sent to the Trans-Mississippi District from Vicksburg. This was known as the "Fairplay Affair." A shipment of 18,000 weapons was sent to Pine Bluff. But 5,000 of them were captured by Union forces. Another 2,500 were sent to Major-General Richard Taylor's army in Louisiana. Only 11,000 weapons reached Pine Bluff. These weapons were mostly old and unusable ones from state armories. They had been returned after Confederate armies east of the Mississippi got better captured Union weapons.

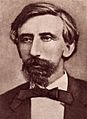

The Arkansas secession convention had shortened the governor's term to two years in 1861. So, an election was needed in fall 1862. Colonel Harris Flanagin was elected governor of Arkansas. After he was called back from active duty, his government mainly dealt with war issues. These included keeping order and continuing government during an invasion. His government faced shortages, rising prices, and caring for soldiers' families.

Hindman's aggressive actions led to complaints that he was ruling like a military dictator. This caused the Confederate government to send Lieutenant-General Theophilus H. Holmes to take command of the new Trans-Mississippi Department. Hindman remained as commander of the 1st Corps of the Trans-Mississippi Army. He led this new force, mostly made of conscripts, to try and clear northwest Arkansas of Union forces. Hindman's attack ended in defeat at Prairie Grove on December 7, 1862.

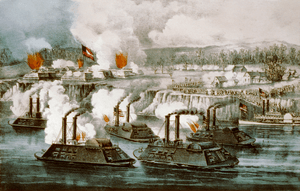

1863: Union Advances and a New Capital

The new year did not bring good news for Confederates in Arkansas. When the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863, Union forces occupied northwestern Arkansas. Union commanders quickly put the Proclamation into effect, freeing many enslaved people in the area. In 1862, the Confederate Army had built a huge defensive earthwork at Arkansas Post on the Mississippi River. It was called Fort Hindman. It was on a bluff 25 feet above the river, with a mile-long view up and downriver. It was meant to stop Union forces from going upriver to Little Rock and to disrupt Union movement on the Mississippi. From January 9–11, 1863, Union forces attacked the fort by land and water. They were supported by ironclad gunboats as part of the Vicksburg Campaign. Union forces greatly outnumbered the defenders (33,000 to 5,500). They easily captured the post, and most of the Confederate soldiers surrendered.

The Battle of Fayetteville happened on April 18, 1863. Confederate General William Cabell attacked the federal outpost in Northwest Arkansas. This was a true civil war struggle between Arkansas Confederates and Arkansas Unionists. The attack failed, and Union forces held the area. However, the attack showed the post's weakness. Union troops were pulled back to Missouri a week later.

General Hindman was moved to a new command east of the Mississippi in the Army of the Tennessee. This left Holmes and Major General Sterling Price of Missouri in command in Arkansas. Arkansas troops spent much of the winter and spring camped near Little Rock. Under pressure from Richmond to ease federal pressure on Vicksburg, Mississippi, General Holmes moved his army across the state. He attacked the Union supply depot at Helena. The Confederate attack was stopped at the Battle of Helena on July 3, 1863. This was the same day Vicksburg fell to Union forces. In late August 1863, Union forces from Indian Territory moved on Fort Smith. They captured the city on September 1, 1863. In July 1862, Lincoln had appointed Colonel John S. Phelps as Military Governor of Arkansas, but he resigned soon after due to poor health.

With the Union base at Helena secure, Major-General Frederick Steele decided to take the state capital at Little Rock. Price, commanding the District of Arkansas, tried to stop Steele's advance with his cavalry. He also strengthened the northern defenses of the city. Fights happened at Brownsville, West Point, Harrison's Landing, Reed's Bridge, and Ashley's Mills. Steele eventually went around Price's defenses by crossing the Arkansas River. He attacked from the south side of the river. Confederate forces fought this attack at the Battle of Bayou Fourche on September 10, 1863. In the end, Price decided to leave the city rather than risk being trapped. Confederate forces retreated to southwestern Arkansas for winter. Governor Flanagin took the state records and moved first to Arkadelphia, then to Washington in Hempstead County. There, he set up a new capital.

After Little Rock fell, Governor Flanagin ordered militia regiments from several counties to provide mounted companies for new state troops. This helped create new mounted companies. These companies fought against Union General Steele's Camden Expedition in spring 1864. The fall of Little Rock also allowed a new pro-Union state government to be formed.

1864: Continued Fighting

The fall of Little Rock to Union troops in 1863 led to a new Union government under Isaac Murphy on April 18, 1864. The Murphy government struggled to be recognized as the true state government. President Lincoln and radical Republicans in Congress argued over terms for states that had left the Union. With Little Rock and Fort Smith under Union control, many Union forces were moved from Arkansas. They went to help armies fighting east of the Mississippi River. This left the Murphy government powerless outside areas controlled by Union soldiers. Intense guerrilla warfare (small, unofficial fighting) broke out in the area north of the Arkansas River and into southern Missouri.

The next major military action in Arkansas was the Camden Expedition (March 23 – May 2, 1864). Steele and his United States Army troops from Little Rock and Fort Smith were ordered to march to Shreveport, Louisiana. There, Steele was supposed to meet another Federal expedition coming up the Red River Valley. The combined Union force would then attack into Texas. However, the two groups never met. Steele's columns suffered terrible losses in battles with Confederates led by Sterling Price and General E. Kirby Smith. These battles included Battle of Marks' Mills, Battle of Poison Spring, and the Battle of Jenkins' Ferry. Union forces eventually managed to escape back to Little Rock. They mostly stayed there for the rest of the war.

The Confederate victory in the Red River Campaign and its Arkansas part, the Camden Expedition, gave Arkansas Confederates a short chance. Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby was sent to northeast Arkansas with his cavalry. He began recruiting new soldiers. Throughout summer 1864, Confederate strength in northeast Arkansas grew. Many men who had left or been separated from their units returned to Confederate service. The last new Confederate units were formed during this time. These were the 45th through 48th Arkansas Mounted Infantry units. Several existing Arkansas units became mounted infantry and were sent to northeast Arkansas.

With these stronger units, Shelby could seriously threaten Union supply lines along the Arkansas River. These lines ran between Helena and Little Rock. For a time, it seemed Confederates might try to retake the Union-held state capital. However, Confederate leaders in Richmond pressured Smith to send some of his infantry to help Confederate armies east of the Mississippi. This caused an uproar among Arkansas Confederate infantry. As a compromise, Smith approved Price's plan for a large cavalry raid into Missouri. This raid would happen around the time of the U.S. presidential election. Arkansas cavalry played a major role in this Confederate attack into Union territory. It lasted from August 29 to December 2, 1864. After Price's huge defeat at Westport on October 23, all Arkansas cavalry units returned to the state. Most were then sent home for the rest of the Civil War.

1865: The War Ends

On April 9, 1865, the Third Arkansas was among the regiments that surrendered with the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox. The remaining soldiers of Patrick Cleburne's division of Arkansas troops surrendered with the Army of Tennessee at Bennett Place near Durham Station, North Carolina, on April 26, 1865. The Jackson Light Artillery was among the last Confederate troops east of the Mississippi to surrender. They helped defend Mobile and surrendered with the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana. The battery disabled its cannons and surrendered at Meridian, Mississippi, on May 11, 1865.

The Arkansas infantry regiments in the Department of the Trans-Mississippi surrendered on May 26, 1865. When the Trans-Mississippi Department surrendered, all Arkansas infantry regiments were camped near Marshall, Texas. War-torn Arkansas could no longer feed the army. The regiments were ordered to report to Shreveport, Louisiana, to be officially released from service. None of them did so. Some soldiers went to Shreveport on their own, but the regiments simply broke up without formally surrendering.

Most Arkansas cavalry units surrendered under Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson. He commanded the Army of the Northern Sub-District of Arkansas. General Thompson agreed to surrender his command at Chalk Bluff on May 11, 1865. He agreed to have his men gather at Wittsburg and Jacksonport to give up their arms and receive their paroles (official release from military service). The cavalry units formally surrendered and were paroled at Wittsburg on May 25 or at Jacksonport on June 5. Thompson surrendered about 7,500 men in total. Many smaller groups surrendered at various Union posts, including Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, and Little Rock in May and June 1865.

The United States government held the Fort Smith Council at Fort Smith in September 1865. These meetings were to discuss future treaties and land for Indian tribes east of the Rockies after the Civil War. Under the Military Reconstruction Act, Congress allowed Arkansas to rejoin the Union in June 1868. It was the second former Confederate state to rejoin (after Tennessee in July 1866).

Battles in Arkansas

Here is a list of American Civil War battles fought in Arkansas between 1862 and 1865:

| Battle | Start | End |

|---|---|---|

| Skirmish at Adam's Bluff | June 30, 1862 | June 30, 1862 |

| Battle of Arkansas Post | January 9, 1863 | January 11, 1863 |

| Action at Ashley's Station | August 24, 1864 | August 24, 1864 |

| Skirmish at Ashley's Mills | September 7, 1863 | September 7, 1863 |

| Engagement at Bayou Fourche | September 10, 1863 | September 10, 1863 |

| Skirmish at Brownsville | August 25, 1863 | August 25, 1863 |

| Battle of Cane Hill | November 28, 1862 | November 28, 1862 |

| Battle of Chalk Bluff | May 1, 1863 | May 2, 1863 |

| Battle of Dardanelle | January 14, 1865 | January 14, 1865 |

| Battle of Devil's Backbone | September 1, 1863 | September 1, 1863 |

| Battle of Dunagin's Farm | February 17, 1862 | February 17, 1862 |

| Battle of Elkin's Ferry | April 3, 1864 | April 4, 1864 |

| Action at Fayetteville | April 18, 1863 | April 18, 1863 |

| Action at Fitzhugh's Woods | April 1, 1864 | April 1, 1864 |

| Action at Fort Smith | July 31, 1864 | July 31, 1864 |

| Battle of Helena | July 4, 1863 | July 4, 1863 |

| Battle of Hill's Plantation | July 7, 1862 | July 7, 1862 |

| Battle of Ivey's Ford | January 17, 1865 | January 17, 1865 |

| Engagement at Jenkins' Ferry | April 30, 1864 | April 30, 1864 |

| Skirmish at Jonesboro | August 2, 1862 | August 2, 1862 |

| Skirmish at L' Anguille Ferry | August 3, 1862 | August 3, 1862 |

| Battle of Marks' Mills | April 25, 1864 | April 25, 1864 |

| Action at Massard Prairie | July 27, 1864 | July 27, 1864 |

| Battle of Mount Elba | March 30, 1864 | March 30, 1864 |

| Battle of Old River Lake | June 5, 1864 | June 6, 1864 |

| Battle of Elkhorn Tavern | March 6, 1862 | March 8, 1862 |

| Action at Pine Bluff | October 25, 1863 | October 25, 1863 |

| Skirmish at Pitman's Ferry | October 27, 1862 | October 27, 1862 |

| Battle of Poison Spring | April 18, 1864 | April 18, 1864 |

| Action at Pott's Hill | February 16, 1862 | February 16, 1862 |

| Battle of Prairie D' Ane | April 9, 1864 | April 14, 1864 |

| Battle of Prairie Grove | December 7, 1862 | December 7, 1862 |

| Battle of Reed's Bridge | August 27, 1863 | August 27, 1863 |

| Battle of Saint Charles | June 17, 1862 | June 17, 1862 |

| Battle of Salem | March 13, 1862 | March 13, 1862 |

| Skirmishes at Taylor's Creek and Mount Vernon | May 11, 1863 | May 11, 1863 |

| Skirmish at Terre Noire Creek | April 2, 1864 | April 2, 1864 |

| Battle of Van Buren | December 28, 1862 | December 28, 1862 |

| Action at Wallace's Ferry | July 26, 1864 | July 26, 1864 |

| Battle of Whitney's Lane | May 19, 1862 | May 19, 1862 |

Important Confederate Leaders from Arkansas

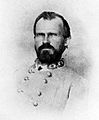

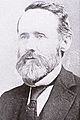

Some important Arkansans during the Civil War include Confederate Major-General Patrick Cleburne. Many consider him one of the smartest Confederate division commanders of the war. Cleburne is often called "The Stonewall of the West." Also important is Major-General Thomas C. Hindman, a former U.S. Representative. He led Confederate forces at the Battle of Cane Hill and Battle of Prairie Grove.

-

Major General

Patrick Cleburne -

Governor

Harris Flanagin -

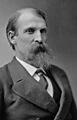

Senator

Augustus H. Garland -

Major General

Thomas C. Hindman -

Governor

Simon P. Hughes -

Senator

Robert W. Johnson -

Brigadier General

James M. McIntosh -

Brigadier General

Nicholas B. Pearce -

Brigadier General

Albert Pike -

Governor

Henry M. Rector

Important Union Leaders from Arkansas

Even though Arkansas sided with the Confederacy, not all Arkansans supported it. After Union forces took Little Rock in 1863, Arkansans who supported the Union formed military units. They created four infantry regiments, four cavalry regiments, and an artillery battery for the United States Army. Also, six infantry regiments and one artillery battery of African American soldiers were formed in the state. These units were first called "1st-6th Arkansas Volunteers of African Descent." Later, they were renamed the 46th, 54th, 56th, 57th, 112th, and 113th United States Colored Troops.

-

Colonel

Elisha Baxter -

Brigadier General

Powell F. Clayton -

Governor

Isaac Murphy -

Colonel

John E. Phelps -

Military Governor

John S. Phelps

Arkansas Rejoins the Union

During the Reconstruction period, Arkansas and Mississippi were part of the Fourth Military District of the U.S. Army. Generals Edward Ord, Alvan Cullem Gillem, and Adelbert Ames commanded this district at different times.

Arkansas had to meet certain requirements to rejoin the Union. This included approving changes to the U.S. Constitution to end slavery and give citizenship to former enslaved people. After meeting these rules, Arkansas's representatives were allowed back into Congress. The state fully rejoined the United States on June 22, 1868. It was the second former Confederate state to be readmitted (after Tennessee in July 1866).

Image gallery

- Arkansas in the American Civil War gallery

See also

In Spanish: Arkansas en la Guerra de Secesión para niños

In Spanish: Arkansas en la Guerra de Secesión para niños

- Arkansas Civil War Confederate Units

- Arkansas Militia in the Civil War

- Confederate States of America - animated map of state secession and confederacy

- List of Arkansas Union Civil War Units

- History of slavery in Arkansas

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |