Ohlone facts for kids

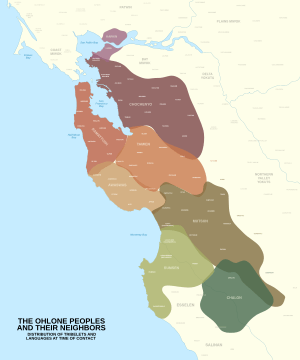

Map of the Ohlone peoples and their neighbors

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1770: 10,000–20,000 1800: 3000 1852: 864–1000 2000: 1500–2000+ 2010: 3,853 |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| California: San Francisco, Santa Clara Valley, East Bay, Santa Cruz Mountains, Monterey Bay, Salinas Valley | |

| Languages | |

| Ohlone (Costanoan): Awaswas, Chalon, Chochenyo, Karkin, Mutsun, Ramaytush, Rumsen, Tamyen English, Spanish |

|

| Religion | |

| Kuksu (formerly) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ohlone Tribes & Villages |

The Ohlone people, also known as Costanoans, are Native American groups from the coast of Northern California. The name "Costanoan" comes from a Spanish word meaning 'coast dweller'. When Spanish explorers arrived in the late 1700s, the Ohlone lived along the coast from San Francisco Bay down to the lower Salinas Valley. They spoke many related languages, which are part of the larger Utian language family.

Before the Spanish arrived, the Ohlone lived in more than 50 different groups. They did not see themselves as one big group. They were hunter-gatherers, meaning they found food by hunting, fishing, and gathering plants. This was a common way of life in California at the time. These groups traded and interacted with each other. The Ohlone people also practiced a religion called Kuksu. Northern California was a very populated area before the Gold Rush.

However, when Spanish colonizers came in 1769, life for the Ohlone changed greatly. The Spanish built missions along the coast to introduce Christianity and Spanish culture. Between 1769 and 1834, the number of Native Californians dropped significantly. After California became part of the United States in 1850, the Ohlone people faced further hardship and violence. Many Ohlone today are working to gain recognition for their tribes and to share their history and culture.

Today, Ohlone people belong to several groups, many still living in their traditional lands. For example, the Tamien Nation lives in the Santa Clara Valley. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe has members from the San Francisco Bay Area. The Ohlone/Costanoan Esselen Nation is centered in Monterey. The Amah Mutsun tribe lives inland from Monterey Bay. These groups are working to be officially recognized by the federal government.

Contents

Understanding the Ohlone Name

The name "Costanoan" was first used by a British expert named Robert Gordon Latham. He used it for different Native American tribes in the San Francisco Bay Area who spoke similar languages. The name came from a group near Mission Dolores called "Olhones" or "Costanos." Later, in the early 1900s, an American anthropologist named Clinton Hart Merriam used "Olhonean." Eventually, "Ohlone" became the most common name used by experts and in books.

Ohlone Way of Life

Life Before European Contact

The Ohlone people lived in fixed villages but moved temporarily to gather seasonal foods like acorns and berries. Their territory stretched from the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula down to Big Sur. It also went from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Diablo Range in the east. This large area included the San Francisco Peninsula, Santa Clara Valley, Santa Cruz Mountains, and the Monterey Bay area. It also covered parts of present-day Alameda County, Contra Costa County, and the Salinas Valley.

Before the Spanish arrived, the Ohlone had about 50 different groups or "tribes." Each group had about 50 to 500 members, with an average of 200. More than 50 specific Ohlone tribes and villages have been recorded. These villages traded, married, and held ceremonies together. They also had some conflicts. Ohlone culture included basket-weaving, seasonal dances, female tattoos, and piercings.

The Ohlone mainly got their food by hunting and gathering. They also managed the land by setting fires each year. This helped new plants grow for seeds. Their main foods were crushed acorns, nuts, grass seeds, and berries. They also ate other plants, hunted animals, fish, and seafood. This included mussels and abalone from the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean. These food sources were plentiful and managed carefully.

Animals in their area included grizzly bears, elk, pronghorn, and deer. The streams had salmon, perch, and stickleback. Birds like ducks, geese, quail, and yellow-billed magpies were common. Waterfowl were important for food. They were caught with nets and decoys. Along the ocean and bays, there were also otters, whales, and many sea lions.

In the valleys and along the bayshore, the Ohlone built dome-shaped houses. These were made of woven mats of tules, about 6 to 20 feet wide. In the hills, where redwood trees grew, they built cone-shaped houses. These used redwood bark attached to a wood frame. The main village building was the sweat lodge. It was built low to the ground with walls of earth and a roof of earth and brush. They used boats made of tule to travel on the bays. These boats were moved with double-bladed paddles.

In warm weather, men often did not wear clothes. In cold weather, they might wear animal skin or feather capes. Women usually wore deerskin aprons, tule skirts, or shredded bark skirts. On cool days, they also wore animal skin capes. Both men and women wore necklaces, shell beads, and pendants. These decorations often showed their status in the community.

Ohlone Plants and Uses

The Ohlone people used many different plants. You can find a full list of their plant uses online. For example, they used the roots of many types of Carex plants for making baskets.

Kuksu Religion and Beliefs

It's important to know that the spiritual beliefs of all Ohlone people were not exactly the same. Because many Native people were moved to the Spanish Missions, different cultural groups are now working to learn about their ancestors' history. Their religion varied by group, but they shared some common ideas.

The Ohlone's spiritual beliefs before European contact were not fully written down by missionaries. The Ohlone likely practiced Kuksu, a type of shamanism. This was common among many tribes in Central and Northern California. Kuksu involved special dances and ceremonies with traditional costumes. It also included an annual mourning ceremony, rites of passage for young people, and talking with the spirit world. There was an all-male group that met in underground dance rooms.

Kuksu was shared with other Native groups in Central California. These included the Miwok, Esselen, Maidu, Pomo, and northernmost Yokuts. However, some experts believe the Ohlone had a less complex version of Kuksu compared to other tribes.

The reasons why Ohlone people joined the Spanish missions are still debated. Some say they were forced to become Catholic. Others say forced baptism was not allowed by the Catholic Church. However, everyone agrees that Native people who were baptized and tried to leave the missions were forced to return. The first conversions to Catholicism happened at Mission San Carlos Borromeo in 1771. In the San Francisco Bay area, the first baptisms were at Mission San Francisco in 1777. Many early conversions to Catholicism during the Mission Era might not have been fully accepted by the Native people.

It is clear that the Ohlone had special medicine people in their tribes. Some healed using herbs. Others were shamans who were believed to heal by talking to the spirit world. Some shamans used dancing, ceremonies, and singing to heal. Some shamans were also thought to be able to see or change the future. They could bring good or bad luck to the community.

Indian Canyon: Sacred Spaces

Some Ohlone groups built prayer houses, also called sweat lodges. These were for ceremonies and spiritual cleansing. These lodges were built near streams because water was seen as very healing. Men and women would gather in sweat lodges to "cleanse, purify, and empower themselves" for tasks like hunting or spirit dancing.

Today, there is a place in Hollister called Indian Canyon. A traditional sweat lodge, or Tupentak, has been built there for ceremonies. A large round house, or upen-tah-ruk, was also built. These areas are used for tribal meetings, traditional dances, ceremonies, and education. Indian Canyon is important because it is open to all Native American groups. They can hold traditional practices there without government rules. Indian Canyon is also home to many Ohlone people, especially the Mutsun band. It is a place for education, culture, and spirituality for all visitors. Indian Canyon helps Native people connect with their heritage and ancestral beliefs.

Sacred Stories and Myths

Storytelling has been a very important part of Ohlone culture for thousands of years. It is still important today. These stories often teach moral or spiritual lessons. They show the cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs of the tribe. Since not all Ohlone groups were the same, their stories are unique to each tribe.

Only a few sacred stories survived the Spanish colonization in the 1700s and 1800s. Many Ohlone groups today use old records to rebuild their sacred stories. This is because some Ohlone people in the missions shared their stories with researchers. However, these stories might not always be complete or perfectly translated.

Many Ohlone groups today feel it is their job to bring these stories back. They discuss them with cultural leaders and other Ohlone people to understand their meanings. This process helps the Ohlone piece together their ancestors' cultural identity and their own. By sharing these stories with the public, the Ohlone show that their culture is not gone. It is alive and seeking recognition.

Ohlone stories and legends often featured the Coyote trickster spirit. Other important figures were Eagle and Hummingbird. In the Chochenyo region, there was also a falcon-like being named Kaknu. The Coyote spirit was smart but also tricky, greedy, and sometimes irresponsible. He often competed with Hummingbird, who usually outsmarted him despite being small. Ohlone creation stories say the world was once covered in water. Only a single peak, Pico Blanco near Big Sur (or Mount Diablo in the northern Ohlone version), stood above the water. Coyote, Hummingbird, and Eagle were on this peak. Humans were believed to be descendants of Coyote.

Ohlone History

Early Times (Before 1769)

Most experts believe that the first people came to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. They crossed a land bridge called Bering Strait. However, one expert, Otto von Sadovszky, believes the Ohlone and some other northern California tribes came from Siberia by sea around 3,000 years ago.

Some experts think these people moved from the San Joaquin–Sacramento River system. They arrived in the San Francisco and Monterey Bay Areas around 600 CE. They may have replaced or mixed with earlier groups. Old shell mounds in Emeryville and Newark suggest villages existed there around 4000 BCE.

By studying artifacts in these shell mounds, experts have identified three periods of early Bay Area history. The "Early Horizon" was from about 4000 BCE to 1000 BCE. The "Middle Horizon" was from these dates to 700 CE. The "Late Horizon" was from 700 CE until the Spanish arrived in the 1770s.

The Mission Era (1769–1833)

The arrival of Spanish missionaries and settlers in the mid-1700s greatly changed the lives of the Ohlone. The Ohlone lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Their culture was stable until the Spanish arrived. The Spanish had two main goals: to introduce Christianity to Native Americans and to expand Spain's land claims.

The Rumsien were the first Ohlone people to be recorded by the Spanish in 1602. Explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno reached and named the area that is now Monterey. Nothing else happened for over 160 years. In 1769, the next Spanish expedition arrived in Monterey. It was led by Gaspar de Portolà and included Franciscan missionaries. Their goal was to build a chain of missions to bring Christianity to the Native people. Under Father Junípero Serra's leadership, the missions introduced Spanish religion and culture to the Ohlone.

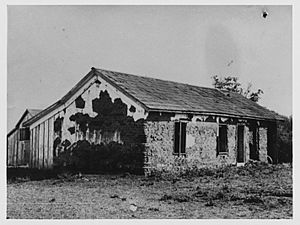

Spanish mission life soon changed the Ohlone's social structures and way of life. Under Father Serra, the Spanish Franciscans built seven missions in the Ohlone region. Most Ohlone people were brought into these missions to live and work. The missions in the Ohlone area were: Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo (1770), Mission San Francisco de Asís (1776), Mission Santa Clara de Asís (1777), Mission Santa Cruz (1791), Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad (1791), Mission San José (1797), and Mission San Juan Bautista (1797).

The Ohlone who lived at the missions were called Mission Indians. They were mixed with other Native American groups, like the Coast Miwok. Spanish military bases were set up at the Presidio of Monterey and the Presidio of San Francisco. For the first 20 years, the missions slowly gained people. Between 1794 and 1795, many Bay Area Native Americans were baptized and moved into Mission Santa Clara and Mission San Francisco. This was followed by a severe epidemic and food shortages. Many people died or ran away from the missions. When missionaries sent people to bring runaways back, illnesses spread outside the missions.

Native populations did not do well as the missions grew. About 81,000 Native people were baptized, and 60,000 deaths were recorded. Most deaths were from European diseases like smallpox and measles, which Native people had no protection against. Other causes included big changes in diet, harsh living conditions, and unclean environments.

Land and Property

Under Spanish rule, it was unclear who owned the mission lands. There were "heated debates" between the Spanish government and the Catholic Church over who controlled the missions. The Franciscan priests argued that the "Missions Indians" owned both land and cattle. They represented the Native people in a complaint against settlers from San Jose. The priests said the settlers' animals were damaging the Native people's crops. They also said the Native people had the right to protect their property. By law, mission property was supposed to go to the Mission Indians after about ten years. During that time, the Franciscans held the land in trust for the Native people.

Secularization (After 1834)

In 1834, the Mexican government ordered all California missions to be secularized. This meant all mission land and property were given to the government. The Ohlone were supposed to receive land, but few did. Most of the mission lands went to other administrators. The Ohlone became laborers and vaqueros (cowboys) on Mexican-owned ranches.

Survival and Challenges

The Ohlone eventually gathered in mixed-ethnic communities called rancherias. These included other Mission Indians from different language groups. Many Ohlone who survived Mission San Jose went to work at Alisal Rancheria in Pleasanton and El Molino in Niles. Communities of mission survivors also formed in Sunol, Monterey, and San Juan Bautista. In the 1840s, American settlers moved into the area, and California became part of the United States. The new settlers brought more diseases to the Ohlone.

The Ohlone population dropped greatly between 1780 and 1850. This was due to low birth rates, high infant deaths, diseases, and social changes from European settlement. By 1852, the Ohlone population was only about 864–1,000 people and continued to decline. By the early 1880s, the northern Ohlone groups were almost gone. The southern Ohlone were also greatly affected and lost most of their land. To highlight the struggles of California Indians, writer Helen Hunt Jackson published accounts of her travels among the Mission Indians in 1883.

Isabel Meadows, who died in 1939, was thought to be the last person who spoke an Ohlone language fluently (Rumsen). Today, descendants are working to bring back the Rumsen, Mutsun, and Chochenyo languages.

Ohlone Sacred Sites and Burials

Important Sites and Practices

The arrival of the Spanish in 1776 greatly impacted the Ohlone's culture, independence, religion, and language. Before the Spanish came, the Ohlone had about 500 shellmounds along the San Francisco Bay. Shellmounds are places where Ohlone people lived, died, and often buried their dead. These mounds are mostly made of shells, with some animal bones, plants, and other materials left by the Ohlone over thousands of years. They are direct evidence of village life.

One idea is that the huge amount of shells shows Ohlone ritual behavior. They might have spent months mourning their dead and eating large amounts of shellfish. These shells were then added to the growing mounds. Shellmounds were found all over the San Francisco Bay area, near waterways. San Bruno Mountain is home to the nation's largest untouched shellmound. These mounds also served a practical purpose. They protected villages from high tides and provided high ground for boats to navigate on San Francisco Bay. The Emeryville Shellmound was over 60 feet tall and 350 feet wide. It was believed to be used between 400 and 2800 years ago.

Ohlone burial practices changed over time. Before the Spanish arrived, cremation was preferred. After cremation, loved ones would place ornaments and other valuable items as offerings to the dead. The Ohlone believed this would bring good fortune in the afterlife. Many of these items have been found in and around the shellmounds. They include shell beads, ornaments, and everyday tools made of stone and bone. These burials also show family histories and land rights. The mounds were important cultural statements. The villages on top were clearly visible, and the mounds had a strong sacred feeling.

Current Burial and Sacred Sites

West Berkeley Shellmound The West Berkeley Shellmound in Berkeley, California, is thought to be the oldest known living site in the San Francisco Bay Area. Most of it was removed by the early 1900s. However, human remains and artifacts are still found during construction projects. Local Ohlone groups have worked to protect a part of it and have it returned to their use.

Glen Cove (Sogorea Te') The City of Vallejo, California built Glen Cove Waterfront Park despite years of protests from Ohlone people. They said the location was a sacred site called Sogorea Te'. It was one of the last Native village sites in the San Francisco Bay that had not been developed.

Santa Cruz A 6,000-year-old grave site was found at a construction site in Santa Cruz. Protesters have demonstrated there, holding signs and talking to people. They want to bring attention to the site.

San Jose Ohlone remains were found in 1973 near Highway 87 during housing development. Some remains were moved during the highway construction. Mt. Umunhum (Dove Mountain) is a very sacred place for the Tamien Nation. It is part of their stories about a Great Flood.

Fremont In 2017, construction workers found 32 sets of Ohlone remains at a housing development. The remains were reburied at the site with the help of a Native consultant.

Bringing Back Ohlone Heritage

The strong desire to protect sacred land is driven by the wish to bring back and preserve Ohlone culture. Native people today are doing a lot of research to rediscover the knowledge, stories, beliefs, and practices from before the Spanish arrived. The Spanish greatly harmed Ohlone culture by causing many deaths and forcing people to adopt new ways of life. After the Americans came, many land claims were fought in court. Protecting their burial sites helps the Ohlone gain recognition as a cultural group.

Site CA-SCL-732- Kaphan Umux or Three Wolves Site The Muwekma Ohlone tribe is actively working to revive Ohlone culture in the East and South Bay. A key part of their success is their involvement in studying their ancestors' remains at ancient burial sites. This helps them "recapture their history and to reconstruct the present and future of their people." Only some sacred stories survived from Ohlone elders living in the missions. This makes it hard to understand pre-contact Ohlone sites because much of the meaning is unknown.

The Muwekma see their involvement in archaeological projects as a way to unite tribal members. It also helps them reconnect with their pre-contact ancestors. They do this by analyzing remains and helping write archaeological reports. One important site the Muwekma tribe helped excavate is CA-SCL-732 in San Jose, dating back to 1500-2700 BCE. In this site, found in 1992, the remains of three ritually buried wolves were found among human remains. In another grave, two more wolf skeletons were found with braided cords around their necks. Many other animal remains were found, like deer, squirrel, and bear. It was clear that the animals were buried in a special way, along with beads and other decorations.

The Muwekma and the archaeological team studied these findings to learn about Ohlone beliefs before European contact. They used known Ohlone stories and other Central California beliefs to understand the possible connection between animals and the Ohlone in these burials. They came up with three ideas: animals were like family groups, animals were "dream helpers" or spirit allies, or animals represented "sacred deity-like figures."

Indian People Organizing for Change

Indian People Organizing for Change (IPOC) is a group in the San Francisco Bay Area. Its members, including Ohlone tribal members, work for social and environmental justice for Native Americans in the Bay Area. One of their main projects is protecting Bay Area shellmounds. These are sacred burial sites of the Ohlone Nation. IPOC has raised awareness through shellmound walks and has pushed for the protection of sacred sites in places like Emeryville Mall and Glen Cove.

Sogorea Te Land Trust

The Sogorea Te Land Trust was started by IPOC members in 2012. Its goals are to return traditional Chochenyo and Karkin lands in the San Francisco Bay Area to Native care. It also aims to build stronger relationships with the land. The trust also started the Shuumi Land Tax. This asks non-Native people living on Ohlone land to pay money for the land they live on. This "tax" is not a legal requirement and has no connection to the U.S. government. However, the organization uses the term "tax" to show Native sovereignty.

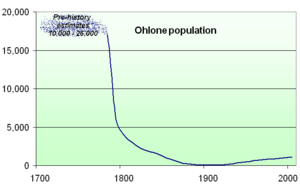

Ohlone Population Over Time

| Population | Source |

|---|---|

| 7,000 | Alfred Kroeber (1925) |

| 10,000 or more | Richard Levy (1978) |

| 26,000 including Salinans "Northern Mission Area" |

Sherburne Cook (1976) |

Experts have different ideas about how many Ohlone people lived in 1769 before European contact. Estimates range from 7,000 to 26,000 (including Salinans). Many modern researchers believe that Alfred L. Kroeber's estimate of 7,000 Ohlone was too low. Later experts like Richard Levy estimated "10,000 or more."

The highest estimate comes from Sherburne F. Cook. He believed there were 26,000 Ohlone and Salinans in the "Northern Mission Area." This area included the Ohlone and Salinan lands between San Francisco Bay and the Salinas River. Cook noted that the Ohlone territory was more densely populated than the southern Salinan territory. Based on his statements, we can estimate about 18,200 Ohlone people.

The Ohlone population dropped sharply after the Spanish arrived in 1769. Cook described the rapid decline of Native populations in California between 1769 and 1900. He stated, "Not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident." The population had fallen to about 10% of its original size by 1848.

The population began to stabilize after 1900. As of 2005, there were at least 1,400 people on tribal membership lists.

Ohlone Languages

The Ohlone language family is often called "Costanoan" or "Ohlone." It is grouped with Miwok languages under the name Utian. Some theories suggest that Ohlone, Miwok, and Yokuts might all be part of a larger Yok-Utian language family.

Eight Ohlone dialects or languages have been recorded: Awaswas, Chalon, Chochenyo, Karkin, Mutsun, Ramaytush, Rumsen, and Tamyen. Today, Ohlone tribes are working to bring back Chochenyo, Mutsun, and Rumsen.

Saving Ohlone Records

Experts began studying the Ohlone people and their languages a long time ago. Alfred L. Kroeber researched California Natives and wrote about the Ohlone from 1904 to 1910. C. Hart Merriam studied the Ohlone in detail from 1902 to 1929. Then, John P. Harrington researched Ohlone languages from 1921 to 1939. He also studied other parts of Ohlone culture, leaving many notes. Other researchers like Robert Cartier, Madison S. Beeler, and Sherburne F. Cook also added to this knowledge. The Ohlone names they used sometimes vary in spelling and meaning. Each expert tried to record and understand this complex society and its languages before the information was lost.

There was some competition among these early scholars. Both Merriam and Harrington did deep research on the Ohlone. They often disagreed with Kroeber. Robert F. Heizer, who worked with Kroeber and Merriam, noted that both Merriam and Harrington "disliked A. L. Kroeber." Harrington focused on Ohlone research for the Smithsonian Institution and did not want to share his findings with Kroeber.

More recent Ohlone historians include Lauren Teixeira, Randall Milliken, and Lowell J. Bean. They all point out that mission records are available, which allows for ongoing research and understanding of Ohlone history.

Notable Ohlone People

- 1777: Xigmacse: He was the chief of the local Yelamu tribe when Mission San Francisco was founded. He is the earliest known San Francisco leader.

- 1779: Baltazar: Baptized from the Rumsen village of Ichxenta in 1775, he became the first Native alcalde (mayor) of Mission San Carlos in 1778. After his family died, he led the first major Ohlone resistance to colonization in 1780.

- 1807: Hilarion and George: These two Ohlone men from the village Pruristac served as alcaldes of Mission San Francisco in 1807.

- 1877: Lorenzo Asisara: A Mission Santa Cruz man who shared three important stories about life at the mission. These stories came from his father.

- 1913: Barbara Solorsano: She died in 1913. She was a Mutsun language expert who worked with C. Hart Merriam from 1902–04.

- 1930: Ascencion Solorsano de Cervantes: She died in 1930. She was a well-known Mutsun doctor and a main language and culture expert for J. P. Harrington.

- 1934: Jose Guzman: He died in 1934. He was one of the main Chochenyo language and culture experts for J. P. Harrington.

- 1939: Isabel Meadows: She died in 1939. She was the last fluent speaker of Rumsen and a key Rumsen expert for J.P. Harrington.

- 2006: Ralph Allan Espinoza: Director and founder of "God Provides - Pomona Valley Food Bank," the only non-profit Native American food bank in the U.S.

- 2016: Ann Marie Sayers: A Mutsun Ohlone leader and tribal chair of Indian Canyon, California. This is the only federally recognized "Indian Country" between Sonoma and Santa Barbara along central coastal California.

See also

In Spanish: Ohlone para niños

In Spanish: Ohlone para niños