Founding Fathers of the United States facts for kids

The Founding Fathers were important men who lived during the American Revolutionary War (around 1775-1783). These men played a big part in creating the United States. They either signed the Declaration of Independence, helped write the Constitution of the United States, or helped the American colonies win their freedom from Britain. Many of them were also members of the Continental Congress. People started using the term "Founding Fathers" for them in 1916.

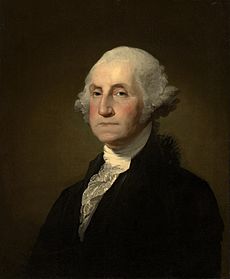

Many people are considered Founding Fathers. Some historians focus on a smaller group of seven: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison.

Most of these men were wealthy landowners or successful business people. Many of them owned slaves. After the Constitution was written, many Founding Fathers became important leaders in the new federal government.

Contents

How the United States Government Began

The First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1774. Fifty-six representatives from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies attended. Important delegates included George Washington, Patrick Henry, and John Adams. This group asked the British king to address their complaints and organized a boycott of British goods.

The Second Continental Congress started on May 10, 1775. Many of the same delegates from the first meeting were there. New important members included Benjamin Franklin and John Hancock. Hancock became the Congress President. Thomas Jefferson also joined. This second Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence.

After declaring independence, the new country needed its own government. They first created the Articles of Confederation. This document set up a national government with one legislative body. Once all thirteen colonies approved it, the Second Congress became known as the Congress of the Confederation. This government lasted from 1781 to 1789.

Later, in the summer of 1787, the Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia. While it was supposed to just fix the Articles of Confederation, many leaders, especially James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, wanted to create a completely new government. The delegates chose George Washington to lead the Convention. The meeting resulted in the United States Constitution, which is still our country's main law today.

Who Were the Framers of the Constitution?

In 1786 and 1787, twelve of the thirteen states chose 74 delegates to attend the Federal Convention in Philadelphia. Not all of them attended. For example, Patrick Henry of Virginia chose not to go. Rhode Island did not send any delegates at all. In the end, no more than 38 delegates were present at any one time.

These delegates were a good example of American leaders in the 1700s. Most were well-educated and successful in their communities. Many were also important in national affairs. Almost all of them had been involved in the American Revolution. At least 29 had served in the Continental Army, often as commanders.

Their Political Experience

The men who wrote the Constitution had a lot of political experience. By 1787, four out of five (41 people) were or had been members of the Continental Congress. Nearly all 55 delegates had experience in their colonial or state governments. Most had also held local government jobs.

- Thomas Mifflin and Nathaniel Gorham had served as President of the Continental Congress.

- Eight men, including Benjamin Franklin and Roger Sherman, had signed the Declaration of Independence.

- Six men, including Daniel Carroll and Roger Sherman, had signed the Articles of Confederation.

- Two men, Roger Sherman and Robert Morris, signed all three major founding documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution.

Their Jobs and Money

The delegates in 1787 had many different jobs, mostly high or middle-status. Many had more than one career at a time.

- Thirty-five had studied law, though not all practiced it. Some were also local judges.

- Thirteen men were merchants (traders).

- Seven were major land speculators (they bought and sold large amounts of land).

- Eleven bought and sold financial securities on a large scale.

- Fourteen owned or managed large slave-operated plantations or big farms. Many wealthy Northerners also owned household slaves. Benjamin Franklin later freed his slaves and helped start the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. John Jay started the New York Manumission Society in 1785, which Alexander Hamilton also joined. These groups worked to end slavery.

- A few delegates were very wealthy, but many had good to excellent financial resources.

Their Backgrounds

Most of the 1787 delegates were born in the Thirteen Colonies. Only nine were born elsewhere, including four from Ireland and two from England. Many had moved from one state to another. Several had also studied or traveled abroad.

The Founding Fathers had strong educational backgrounds. Some, like Franklin and Washington, taught themselves or learned through apprenticeships. Others went to colonial colleges or had private tutors. About half of them had attended or graduated from college. Some had medical degrees or advanced religious training. Many lawyers were trained in London.

Key Founding Documents and Their Signers

The National Archives calls three documents the "Charters of Freedom": the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. These documents protect the rights of Americans and are central to the country's founding ideas. The Articles of Confederation is also considered a founding document.

The people who signed these documents are widely seen as Founding Fathers. The table below lists many of these founders and which documents they signed.

Notes:

Delegates Who Did Not Sign the U.S. Constitution

Besides the 39 signers, some people who helped write the U.S. Constitution but didn't sign it are also considered founders. Here are 16 framers who attended the Constitutional Convention but did not sign the final document:

|

|

Other Important Founders

Beyond those who signed the main documents and the "great seven" (Adams, Franklin, Hamilton, John Jay, Jefferson, Madison, and Washington), many others contributed greatly to the birth of the new nation:

- George Clinton: First governor of New York and later the fourth Vice President of the U.S.

- Patrick Henry: A famous speaker and the first governor of Virginia.

- Robert R. Livingston: A member of the group that wrote the Declaration of Independence and the first U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

- John Marshall: The fourth Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, who helped shape American law.

- James Monroe: The fifth President of the United States.

- Peyton Randolph: The first president of the Continental Congress.

- Charles Thomson: The secretary of the Continental Congress for many years.

- Thomas Paine: Author of very important pamphlets in the 1770s, sometimes called the "Father of the American Revolution."

Images for kids

-

Declaration of Independence, an 1819 painting by John Trumbull, shows the Committee of Five (John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston) giving their draft to the Second Continental Congress on June 28, 1776.

-

Signature page of the Treaty of Paris of 1783 that was negotiated for the United States by John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay.

-

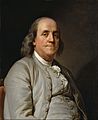

Benjamin Franklin, who supported colonial unity, was a key figure in shaping American ideals.

-

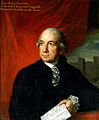

Robert R. Livingston, a member of the group that wrote the Declaration of Independence.

-

Alexander Hamilton was a senior aide to Washington during the Revolutionary War; he wrote many of the Federalist Papers and helped create the government's financial system.

-

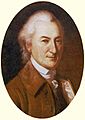

John Jay was president of the Continental Congress, helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris, and wrote The Federalist Papers with Hamilton and Madison.

-

James Madison, known as the "Father of the Constitution."

-

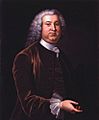

Peyton Randolph, as president of the Continental Congress, oversaw the creation of the Continental Association.

-

Richard Henry Lee, who proposed that the colonies declare independence in the Second Continental Congress.

-

John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, famous for his large signature on the United States Declaration of Independence.

-

John Dickinson, known as the "Penman of the Revolution," wrote important documents like the 1774 Petition to the King and the first draft of the Articles of Confederation.

-

Henry Laurens was president of the Continental Congress when the Articles of Confederation were passed in 1777.

-

Roger Sherman, a member of the Committee of Five, was the only person to sign all four major U.S. founding documents.

-

Robert Morris, known as the "Financier of the Revolution," helped create the financial system of the United States.

-

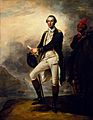

George Washington and his valet slave William Lee, by John Trumbull, 1780.

-

Abigail Adams, a close advisor to her husband John Adams.

-

George Mason, who wrote the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights and helped inspire the United States Bill of Rights.

-

James Monroe served as a delegate from Virginia from 1783-1786.

-

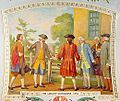

The Albany Congress of 1754 was an early meeting that helped lead to the idea of a united America.

See also

In Spanish: Padres fundadores de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Padres fundadores de los Estados Unidos para niños