Tongva facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,900+ | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Spanish, formerly Tongva | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity |

The Tongva (TONG-və) are an Indigenous group from California. They lived in the Los Angeles Basin and the Southern Channel Islands. This area covers about 4,000 square miles.

Long ago, before Europeans arrived, the Tongva lived in many villages, sometimes as many as 100. They usually identified by their village name, not a single group name. When the Spanish came, they called these people Gabrieleño and Fernandeño. These names came from the Spanish missions built on their land: Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and Mission San Fernando Rey de España. The name Tongva is now widely used by the people themselves. Narcisa Higuera used this name in 1905 to describe people living near Mission San Gabriel.

The Tongva were very important when Europeans first arrived in the Americas. They were influential, along with the nearby Chumash. Over time, different Tongva communities spoke different forms of the Tongva language. This language is part of the Takic group, which is part of the larger Uto-Aztecan language family. There might have been five or more of these languages.

In the early 1900s, some people wrongly believed the Gabrieleño had disappeared. Many Tongva publicly identified as Mexican-American at this time. However, a strong community stayed in touch between Tejon Pass and San Gabriel. Since 2006, four groups have claimed to represent the Tongva people. In 2008, over 1,700 people identified as Tongva or said they had Tongva ancestors. By 2013, the four groups applying for federal recognition had more than 3,900 members. The Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy was created to help return Tongva homelands to their people. In 2022, one acre of land was returned to the conservancy in Altadena. This was the first time the Tongva had land in Los Angeles County in 200 years.

Contents

Tongva Lands and Neighbors

The Tongva people lived in an area that bordered many other tribes. Their historical lands are now parts of Los Angeles County and Orange County. This includes the coastal areas and nearby islands. In 1962, a museum curator named Bernice Johnson said the northern border was near Topanga and Malibu. The southern border was Aliso Creek in Orange County.

What's in a Name?

The Name Tongva

The name Tongva was first used by C. Hart Merriam in 1905. He learned it from many people, including Narcisa Higuera. She lived near Fort Tejon. Merriam's notes show the name is pronounced TONG-vay.

Some Tongva descendants prefer the name Kizh. They believe this is an older and more accurate name. They say it was well recorded in historical documents.

The Name Gabrieleño

The Spanish called the Indigenous people near Mission San Gabriel the Gabrieleño. This was not the name the people used for themselves. Because of its historical use, the term "Gabrieleño" or "Gabrielino" is part of the official names of tribes in this area today.

Tongva History

Life Before the Missions

Evidence suggests the Tongva came from Uto-Aztecan-speaking groups. These groups started in what is now Nevada. They moved southwest to coastal Southern California about 3,500 years ago.

In 1811, priests at Mission San Gabriel recorded at least four languages. Three languages were recorded at Mission San Fernando around the same time. The Tongva spoke a language from the Uto-Aztecan family. The ancestors of the Tongva likely came together as a people in the Sonoran Desert. This was probably between 3,000 and 5,000 years ago.

Most Tongva land was in an area with many natural resources. These included acorns, pine nuts, small animals, and deer. Along the coast, they found shellfish, sea mammals, and fish. Before the Spanish arrived, the Tongva believed humans were part of the web of life. They thought humans, plants, animals, and the land shared a relationship of respect and care. This idea is seen in their creation stories. The Tongva also believed time was not just a straight line. They felt a constant connection with their ancestors.

On October 7, 1542, Spanish explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo reached Santa Catalina. Tongva people greeted his ships in a canoe. The next day, Cabrillo and his men entered a large bay on the mainland. They called it "Bay of Smokes" because of many smoke fires. This is thought to be San Pedro Bay, near today's San Pedro.

The Mission Period (1769–1834)

The Gaspar de Portolá expedition in 1769 was the first time Europeans reached Tongva land by foot. Franciscan padre Junipero Serra was with Portola. Within two years, Serra founded four missions. These included Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, founded in 1771, and Mission San Fernando Rey de España, founded in 1797.

The people made to work at San Gabriel were called Gabrieleños. Those at San Fernando were called Fernandeños. Whole villages were brought into the mission system. This had very difficult results for the people. For example, from 1788 to 1815, people from the village of Guaspet were baptized at San Gabriel.

The Tongva often resisted the mission system. Many people returned to their villages when they died. They also kept using traditional foods and making their own tools. More direct ways of resisting included refusing to join the system, working slowly, and running away. Five major uprisings were recorded at Mission San Gabriel alone.

By the 1800s, San Gabriel was the wealthiest mission. It provided cattle, sheep, and other supplies for settlers throughout Alta California. The mission used forced labor. An ethnologist named Hugo Reid reported that Tongva children were taken from their parents. They were kept behind bars at the mission. They could only leave for church or chores. When they were older, boys and girls worked in the mission's large farms. Soldiers watched them and would hunt down anyone who tried to escape.

In 1810, 1,201 "Gabrieleño" people were recorded working at the mission. This number rose to 1,636 in 1820, then fell to 1,320 in 1830. Resistance to this forced labor continued. In 1817, the San Gabriel Mission recorded "473 Indian fugitives." In 1828, a German immigrant bought the land where the village of Yang-Na stood. He forced the entire community to leave with help from Mexican officials.

Mexican Rule (1834–1848)

The mission period ended in 1834. Mexico took control of the missions. Some "Gabrieleño" people became part of Mexican society. Tongva and other California Natives mostly became workers. Former Spanish leaders received large land grants.

California Natives were often denied land by Mexican landowners. Most Tongva became landless during this time. Whole villages fled inland to escape the changes. Others moved to Los Angeles. The Native population in Los Angeles grew from 200 in 1820 to 553 in 1836.

Several Gabrieleño families stayed in the San Gabriel area. This became a cultural center for the Gabrieleño community. By 1844, most Natives in Los Angeles worked as servants. They served settlers in a system of ongoing servitude.

In 1847, a law was passed. It stopped Gabrielenos from entering the city without proof of a job. The law said that Native people without jobs would be put to work on public projects. In 1848, Los Angeles officially became a U.S. town after the Mexican-American War.

American Rule and Challenges (1848–)

Without land and recognition, the Tongva faced many challenges. They experienced violence and forced labor under American rule. Some people were moved to small Mexican and Native communities. These included areas like Eagle Rock and Highland Park in Los Angeles. Others went to Pauma, Pala, and Temecula. Putting Native people in jail in Los Angeles was a way to show the new laws were in place.

In 1855, the superintendent of Indian affairs, Thomas J. Henley, said the Gabrieleño were in a "miserable condition." However, he noted that moving them to a reservation would be opposed. This was because their labor was useful and cheap, especially during grape season.

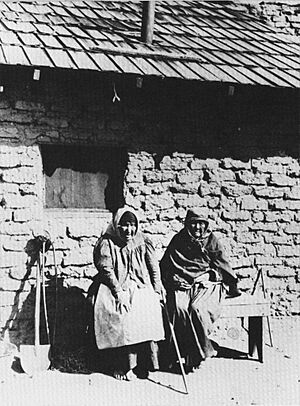

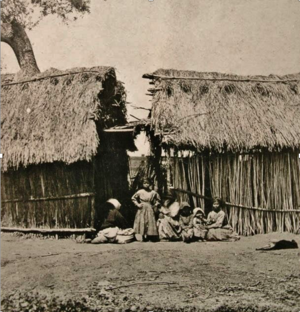

In 1882, Helen Hunt Jackson was sent by the government to check on the Mission Indians. She reported that many people lived like "gypsies in brush huts." They earned a living by working day by day. Even though her report led to a law to set aside land for Mission Indians, the Gabrieleño were "overlooked."

The "Extinction Myth"

By the early 1900s, Gabrieleño identity faced great pressure. Most Gabrieleño publicly identified as Mexican. They learned Spanish and adopted Catholicism. They often kept their Native identity a secret. In schools, students were punished for saying they were "Indian." Many people blended into Mexican-American culture. More attempts to create a reservation for the Gabrieleño in 1907 failed. Soon, local newspapers began to say the Gabrieleño were extinct. In 1921, the Los Angeles Times said the death of Jose de los Santos Juncos, an Indigenous man, "marked the passing of a vanished race." In 1925, Alfred Kroeber also declared Gabrieleño culture extinct. However, scholars now know this "extinction myth" is not true.

Even though they were declared extinct, Gabrieleño children were still sent to schools like Sherman Indian School in Riverside, California. Between 1890 and 1920, at least 50 Gabrieleño children were recorded there. In the 1910s and 1920s, the Mission Indian Federation was formed. The Gabrieleño joined it. This led to a law in 1928 that created official records for California Indians. Over 150 people identified as Gabrieleño on this list. This showed that the Tongva community was still connected and present.

In 1971, Bernice Johnston, a former museum curator, spoke to the Los Angeles Times. She said she almost met some Gabrielenos at the museum. They were asking questions about their own history. She rushed back to them, but they were gone.

Protecting Sacred Sites

It has been hard for the Tongva to protect their sacred sites and artifacts. This is partly because they lack federal recognition. In 2001, a 9,000-year-old village site at Bolsa Chica was badly damaged. Burials near Genga were dug up and moved for building projects.

In 2019, CSU, Long Beach put trash and dirt on Puvunga. This is a sacred site. This caused a long-standing disagreement between the university and the tribe. In 2022, it was announced that part of the Genga village site might become a green space. Project leaders said that "tribal descendants" would have a voice in how the park is developed.

The Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy was created as part of the Land Back movement. This movement aims to return Indigenous lands to their people. The conservancy developed a "guest exchange" program. This is a way for people living on Tongva lands to contribute. In October 2022, a private resident returned one acre of land to the conservancy in Altadena. This was the first time the Tongva had land in Los Angeles County in 200 years.

Tongva Culture

The Tongva lived in a very fertile part of southern California. This area had a pleasant climate and plenty of food. They were seen as a very advanced and wealthy group. They had a thriving trade network. This network stretched from the Channel Islands to the Colorado River. They traded with groups like the Cahuilla, Serrano, Luiseño, Chumash, and Mohave.

Like all Indigenous peoples, the Tongva lived in close connection with nature. Their villages were in four main natural areas. These included mountains, grasslands, coastal canyons, and the open coast. This meant they had many different plants, animals, and minerals. They used these for food and materials. Important plants included oak, willow, chia, cattail, and white sage. Animals included deer, rabbits, eagles, dolphins, and whales.

Te'aat and the Ocean

The Tongva had many people living along the coast. They fished and hunted in the Los Angeles River estuary. Like the Chumash, the Tongva built strong plank canoes called te'aat. They made these from driftwood. They sewed planks together with plant fibers and sealed them with tar. The te'aat could hold up to 20 people and their goods. These canoes were vital for trade between the mainland and the islands. They helped the economy and social life of the region. The Tongva regularly paddled to Catalina Island. There, they gathered abalone from the rocks.

Food Culture

In the Tongva system, the village chief managed food resources. A part of each day's hunt or gathering went to the community's food supply. Families also stored food for times when it was scarce. Villages were built where there was water, shelter, and many different natural resources. This allowed the Tongva to gather plants from several areas nearby.

Homes were main houses called kiiy. They also had temporary shelters for gathering trips. In summer, families gathered roots, seeds, flowers, and greens. In winter, they collected nuts, acorns, and hunted deer. They used wooden tongs to pick prickly pear fruits.

Some groups moved to the coast in winter to fish and hunt. Coastal villages went inland in winter to gather roots and bulbs.

The Tongva did not farm. Their hunting, gathering, and trade provided enough food. They made bread from cattail pollen. They also ground cattail roots into a starchy meal. Chia seeds were very important. They were collected, dried, and ground into a flour called "pinole." This was mixed with water to make a drink or porridge.

Acorn mush was a main food. Acorns were gathered in October by everyone. Men shook the trees, and women and children collected the nuts. Acorns were stored in large wicker granaries above the ground. Preparing acorns took about a week. They were shelled, dried, and pounded into meal. This meal was then washed to remove bitterness. It was cooked by boiling in baskets or soapstone bowls with hot stones.

Men did most of the heavy work. They hunted, fished, helped gather food, and traded. They hunted large animals with bows and arrows. Small animals were caught with traps or clubs. Harpoons and spears were used for marine mammals. Fishing was done from shore or rivers using hooks, nets, and spears. Sharing resources was very important. Hunters would give away large parts of their catch.

Women collected and prepared plant foods. They also made baskets, pots, and clothing. Older women and men cared for the young and taught them Tongva ways of life.

Material Culture

Tongva tools and crafts showed great skill. They knew how to use natural materials well. Many everyday items were decorated with shells, carvings, and paint. Soapstone from Catalina Island was used for cooking tools, carvings, pipes, and ornaments.

Women made coiled and twined baskets using plant stems. These baskets had three-color patterns. They were used for household needs, gathering seeds, and ceremonies. Some baskets were sealed with tar to hold liquids.

The Tongva used tule reeds and cattails to weave mats and thatch their shelters.

In the mild climate, men and children often wore little clothing. Women wore a two-piece skirt. In cold weather, they wore robes made of rabbit fur, deer skins, or bird skins. These were also used as blankets. Along the coast, they used sea otter skins. Women were tattooed with cactus thorns and charcoal.

Social Culture

According to Father Gerónimo Boscana, relations between the Tongva and their neighbors were mostly peaceful. However, when there was war, it was fierce. No prisoners were taken except the wounded.

The Tongva Today

Early studies of the Christianized Tongva (then called Gabrielino) began in the mid-1800s. By this time, their old religious beliefs were fading. The Gabrieleño language was almost gone by 1900. So, only small parts of their language and culture were saved. Gabrieleño is part of the Takic language group, which is part of the Uto-Aztecan family. It has not been spoken daily since the 1940s. Today, Tongva people speak English. But some are trying to bring their language back. They use it in daily talks and ceremonies. It is also used in language classes and discussions about religion and the environment.

Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles has many historical documents about the Tongva.

In the 21st century, about 1,700 people identify as Tongva or Gabrieleño. In 1994, California recognized the Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe and the Fernandino-Tongva Tribe. However, neither has gained federal recognition. In 2013, the four Tongva groups applying for federal recognition had over 3,900 members.

The Gabrieleño/Tongva people do not all agree on one organization to represent them. They have had disagreements about their future. This includes plans by some members to open a gaming casino. Casinos can bring a lot of money to Native American tribes. But not all Tongva people believe the benefits are worth it. The Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe (the "slash" group) and Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe (the "hyphen" group) are the main groups that want a casino. The Gabrielino Tribal Council of San Gabriel, now called the Kizh Nation, does not support gaming. The Gabrieleno Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians also does not support gambling. None of these groups are recognized by the federal government as a tribe.

Casino Discussions

In 1990, the Gabrielino/Tongva of San Gabriel applied for federal recognition. Other Gabrieleño groups have done the same. These applications are still waiting.

The San Gabriel group was recognized as a nonprofit by California in 1994. In 2001, the San Gabriel council split. This was over agreements for a development called Playa Vista and a plan for an Indian casino in Compton, California. A group from Santa Monica formed that supported gaming. The San Gabriel group opposed it.

The San Gabriel council and Santa Monica group sued each other. There were claims that members were removed to increase casino shares. There were also claims that tribal records were stolen to support federal recognition.

In 2006, the Santa Monica group split into the "slash" and "hyphen" groups. These were the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe and Gabrielino-Tongva Tribe. In 2007, the city council of Garden Grove rejected a casino proposal. They chose to build a water park instead.

Land Use Issues

Today, there are disagreements in California about land use and Native American rights. Both the state and U.S. governments have improved their respect for Indigenous rights. The Tongva have gone to court to protect their sacred lands. Because of the long history of Indigenous people in the area, not all ancient sites have been found.

Sometimes, land developers have accidentally disturbed Tongva burial grounds. The tribe spoke out against archeologists breaking bones found during an excavation at Playa Vista. An important agreement was reached at the Playa Vista site.

In the 1990s, the Gabrielino/Tongva Springs Foundation brought back the use of the Kuruvungna Springs for sacred ceremonies. These natural springs are on the site of a former Tongva village. Today, it is the campus of University High School in West Los Angeles. The Tongva see these springs as one of their last sacred sites. They hold ceremonies there regularly.

The Tongva have another sacred area called Puvunga. They believe it is the birthplace of the Tongva prophet Chingishnish. Many believe it is the place of creation. The site has an active spring and was once a Tongva village. It is now part of California State University, Long Beach. A part of Puvungna, a Tongva burial ground, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2019, soil and debris were dumped on this land. This led to a lawsuit against the university. In November 2019, the university agreed to stop dumping materials. The lawsuit was ongoing as of 2020.

Traditional Stories

Not much is known about Tongva traditional stories. This is because they became Christianized early by the Spanish missions. What is known suggests strong cultural ties with their language relatives and neighbors. These include the Luiseño and the Cahuilla.

According to Kroeber (1925), the Tongva had a system of six gods before Christianity. The main god was Chinigchinix, also known as Quaoar. Another important figure was Weywot, the god of the sky. Weywot was created by Quaoar. Weywot was cruel and was killed by his own sons. When the Tongva met to decide what to do, they saw a ghostly being. He called himself Quaoar. He said he came to bring order and give laws to the people. After giving instructions, he danced and slowly went up to heaven.

After talking with the Tongva, astronomers Michael E. Brown and Chad Trujillo named a large object in space 50000 Quaoar (2002) after Quaoar. When Brown found a moon orbiting Quaoar, he let the Tongva choose the name. They picked Weywot (2009).

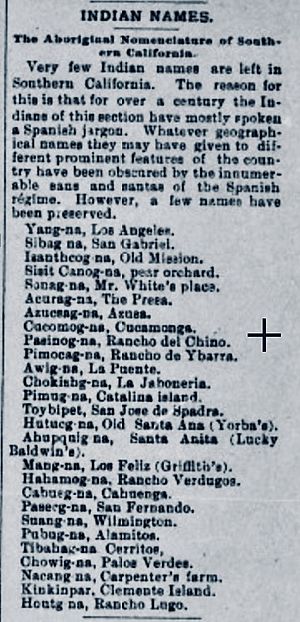

Place Names

Many Tongva place names are now used in Southern California. Examples include Pacoima, Tujunga, Topanga, Rancho Cucamonga, and Azusa.

Sacred sites that still exist include Puvunga, Kuruvungna Springs, and Eagle Rock.

Other places have been named recently to honor Indigenous peoples. The Gabrielino Trail is a 28-mile path in the Angeles National Forest. It was named in 1970.

A mountain peak in the Verdugo Mountains was named Tongva Peak in 2002.

Tongva Park is a 6.2-acre park in Santa Monica, California. It includes an amphitheater, playground, and gardens. The park was opened on October 13, 2013.

Notable Tongva People

- Chief Vera Ya'anna Rocha: A leader who helped protect sacred areas like the Ballona Wetlands.

- Chief Red Blood Anthony Morales: Chairman and tribal leader of the Gabrielino/Tongva Nation. He received the "Heritage Award" in 2008.

- Jimi Castillo: A Gabrielino/Tongva Elder and Pipe Carrier. He received the Heritage Award in 2016 and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Obama White House.

- Tonantzin Carmelo: An actress.

- L. Frank: An artist, author, and language activist.

- Nicolás José: Led two revolts against the Spanish in 1779 and 1785.

- Victoria Reid (~1809–1868): A woman from the village of Comicranga who became a respected landowner.

- Reginald "Reggie" Rodriguez (1948–1969): A Vietnam War hero. A park in Montebello, California is named in his honor.

- Toypurina (1760–1799): A Gabrieliño medicine woman who led a rebellion against the Spanish in 1785.

- Charles Sepulveda: A professor and author.

- Julia Bogany (1948–2021): An educator and cultural consultant.

- Cindy Alvitre: Former tribal leader, educator, and cultural consultant.

- Weshoyot Alvitre: A comic book artist and illustrator.

- Emilio Reyes: A researcher and genealogist.

|

See also

In Spanish: Tongva para niños

In Spanish: Tongva para niños