Geography of Western Australia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Geography of Western Australia |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Continent | Australia |

| Region | Western Australia |

| Coordinates | 26°S 121°E / 26°S 121°E |

| Area | Ranked 1st among states and territories |

| • Total | 2,527,013 km2 (975,685 sq mi) |

| Coastline | 12,889 km (8,009 mi) |

| Borders | Land borders: Northern Territory, South Australia |

| Highest point | Mount Meharry 1,249 m (4,098 ft) |

| Longest river | Gascoyne River 834 km (518 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lake Mackay 3494 km2 |

Western Australia is a huge state, covering almost one-third of the entire Australian continent. It's so big and far away from other places that people often talk about these features. In fact, it's the second-largest administrative area in the world, after Yakutia in Russia.

Even though Australia is only the sixth-largest country, Western Australia takes up a huge part of its land. Its capital city, Perth, is also known for being one of the most isolated cities globally. It's actually closer to Jakarta in Indonesia than to Australia's own capital, Canberra!

Contents

About Western Australia

Western Australia has some of the oldest and newest rocks and landforms. The oldest minerals ever found on Earth were discovered at the Jack Hills. Also, a large part of the state, called the Yilgarn Craton, has been above sea level for over 2.5 billion years! This means it has some of the oldest soils on our planet.

Europeans first settled in Western Australia in 1826, in a place called Albany. But the state officially became a colony in 1829. Much of the state was developed later, with farming starting in the 1860s and mining in the 1890s, which continues today.

Many people in Western Australia were not born there. Also, over 76% of everyone lives in Perth. This means that not many people truly understand the vast geography of their state.

People have been interested in Western Australia's geography since the 1600s. Dutch East India Company explorers were the first to visit. They were sailing from Cape Town to Batavia (now Jakarta) in Indonesia. They often miscalculated their journey and ended up on Western Australia's coast.

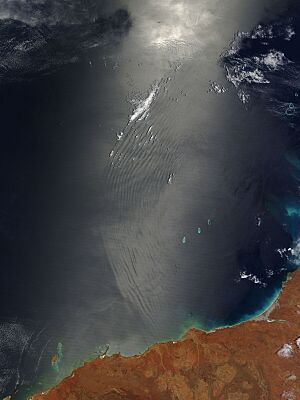

Dutch explorers often crashed into the many reefs along the western coast. This is because of the warm Leeuwin current, which flows along the coast. This current also helps create the nice Mediterranean climate in the state's southwest corner. Famous explorer Abel Janzoon Tasman was even sent to map the new continent.

By the mid-1700s, most of Western Australia's western coastline was mapped pretty well. Later, British explorers like George Vancouver, Phillip Parker King, and Matthew Flinders made these maps even better.

Western Australia's Climate

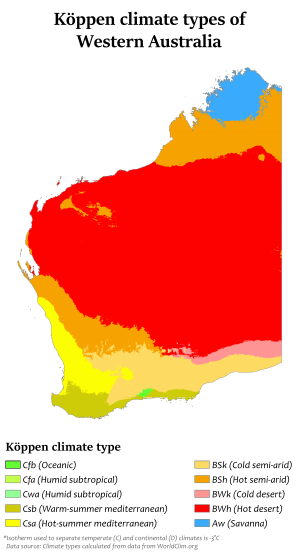

Western Australia's climate is split in half by a band of dry air. This usually happens along the Tropic of Capricorn. The northern part of the state gets most of its rain in summer. The southern part gets most of its rain in winter.

In the north, from May to September, it's generally warm and dry. Winds blow from the land towards the sea. In summer, from November to March, it's humid and tropical. This brings thunderstorms and sometimes a cyclone. These storms bring most of the rain to the region. The strongest wind gust ever recorded in mainland Australia was 259 km/h during Tropical Cyclone Trixie in 1975. Whim Creek holds the record for the most rainfall in 24 hours: 747 mm during a cyclone in 1898.

In the south, most of the rain comes from cold fronts moving from west to east. These fronts start in the Southern Ocean, south of South Africa. Cold air from the south mixes with humid air from the northwest. This causes rain between May and August. In summer, these fronts move further south. This means warm, dry weather usually dominates the southern part of the state.

Because of this, Western Australia has five main climate types. These range from tropical wet-dry climates in the Kimberley region to arid (very dry) climates in the large deserts. There are also semi-arid climates and a Mediterranean climate in the southwest.

Kimberley Region Climate

From April to October, the Kimberley region has dry months with clear blue skies. Daytime temperatures are moderate, and nights are cool. However, the "wet season" is hot and humid. Monsoonal winds bring constant and sometimes very heavy rain. For example, Broome once had 356 mm of rain in just 24 hours!

Cyclones form off the coast. In the 1970s, they only formed twice a year and crossed the coast every two years. But with global warming, this is happening more often. Heavy rain causes rivers to flood. This can lead to lost animals, damaged property, and sometimes even loss of life. Roads can be cut off by floods. Before it was dammed, the Ord River used to pour more than 50 million litres per second into the Cambridge Gulf.

Central and Goldfields Climate

This region has salt lakes and sand dunes. It's covered with desert oaks and mulga trees. Laverton, for example, gets only about 192 mm of rain per year on average. But this rainfall is very unpredictable. The area can go almost a year without rain, then get its whole year's worth in just a few hours!

The Giles Meteorological Station, near the Western Australian border, records only 219 mm of rain per year. Laverton gets most of its rain from cold fronts that sometimes reach the Goldfields. Giles is usually dry from July to September. It gets most of its rain from tropical cyclones that weaken into tropical depressions, bringing sudden rain to the interior.

Gascoyne and Pilbara Climate

This semi-arid region sits between the summer and winter rainfall zones. In the north, Dampier gets 402 mm of rain, with the wettest months in January, February, and March. Carnarvon gets 239 mm of rain, peaking in June and July.

Like the Kimberley, this region has huge tides. The coast is surrounded by mangroves and mudflats. In the past, these areas were important for wild pearls and oysters. Inland, river gorges can have flash floods from sudden downpours. This provides enough water for sheep and cattle farms.

Southwest Region Climate

This region has cool, wet winters and hot, dry summers. Rainfall decreases, and summer temperatures increase the further you get from the sea. Pemberton, in the extreme southwest, gets an average of 1244 mm of rain per year. Bencubbin, in the northeast wheat belt, gets only 319 mm.

Coastal areas usually don't get frosts. But frost is common on winter nights further inland. The state rarely gets snow in winter. However, it's reported once or twice a year on the Stirlings or Porongurups north of Albany. Snow has even been recorded as far north as Wongan Hills, and as late as November. Perth is said to be the second windiest city in the British Commonwealth (after Wellington, New Zealand). In winter, wind gusts of up to 135 km/h are not uncommon.

Ozone Layer and Sun Safety

The southern half of Western Australia is greatly affected by the thinning of the ozone layer. The ozone hole allows more harmful ultraviolet (UV) rays to reach Earth. NASA showed that in 2006, the ozone hole was the biggest ever recorded.

Because of this, about one-third of Western Australians will get skin cancer in their lifetime. This has led to a big change in how people behave. Australians used to love spending time in the sun. Now, they are encouraged to "slip" on a shirt, "slop" on sunscreen (SPF 15+), and "slap" on a hat. We don't know as much about how the ozone hole affects animals or plants in Western Australia. But there have been reports of blind kangaroos with cataracts caused by UV rays.

Climate Change in Western Australia

Experts say that natural environments can absorb about two tonnes of carbon dioxide per person each year. But right now, the world is releasing 6.8 tonnes of carbon dioxide per person each year. This is mainly from burning fossil fuels and clearing forests. Over the last century, carbon dioxide in the air has increased a lot.

Western Australia releases 33.1 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per person. This makes the state one of the highest contributors per person in the world.

Climate Examples

| Climate data for Western Australia (Extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 50.7 (123.3) |

50.5 (122.9) |

48.1 (118.6) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

41.2 (106.2) |

43.1 (109.6) |

46.9 (116.4) |

48.0 (118.4) |

49.8 (121.6) |

50.7 (123.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Perth (Köppen Csa) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.8 (114.4) |

46.2 (115.2) |

42.4 (108.3) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

37.3 (99.1) |

40.4 (104.7) |

44.2 (111.6) |

46.2 (115.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.2 (88.2) |

31.5 (88.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.3 (43.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 18.5 (0.73) |

14.3 (0.56) |

20.4 (0.80) |

35.4 (1.39) |

87.7 (3.45) |

127.3 (5.01) |

142.3 (5.60) |

124.4 (4.90) |

82.7 (3.26) |

37.7 (1.48) |

24.2 (0.95) |

10.4 (0.41) |

730.9 (28.78) |

| Average precipitation days | 2.9 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 6.8 | 11.2 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 9.2 | 5.5 | 3.5 | 108.1 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) (at 15:00) | 39 | 38 | 40 | 46 | 50 | 56 | 57 | 54 | 53 | 47 | 44 | 41 | 47 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 356.5 | 319.0 | 297.6 | 249.0 | 207.0 | 177.0 | 189.1 | 223.2 | 231.0 | 297.6 | 318.0 | 356.5 | 3,221.5 |

| Source 1: Bureau of Meteorology Temperatures: 1993–2020; Extremes: 1897–2020; Rain data: 1993–2020; Relative humidity: 1994–2011 |

|||||||||||||

| Source 2: Time and Date Dew point: 1985-2015 |

|||||||||||||

| Climate data for Albany (Köppen Csb) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.6 (114.1) |

44.0 (111.2) |

41.2 (106.2) |

38.8 (101.8) |

32.6 (90.7) |

24.8 (76.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

39.2 (102.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

45.6 (114.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

1.9 (35.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

0.7 (33.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 23.6 (0.93) |

22.3 (0.88) |

33.6 (1.32) |

61.3 (2.41) |

89.8 (3.54) |

108.0 (4.25) |

119.3 (4.70) |

106.8 (4.20) |

88.5 (3.48) |

70.8 (2.79) |

47.0 (1.85) |

27.8 (1.09) |

798.1 (31.42) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1mm) | 2.8 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 9.9 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 83.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 69 | 71 | 76 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 73 | 70 | 74 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 13 (55) |

13 (55) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

8 (46) |

8 (46) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

12 (54) |

10 (51) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 251.1 | 209.1 | 204.6 | 186.0 | 167.4 | 153.0 | 170.5 | 189.1 | 189.0 | 210.8 | 222.0 | 244.9 | 2,397.5 |

| Source 1: Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Time and Date (humidity and dew point) | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Port Hedland (Köppen BWh) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 49.0 (120.2) |

48.2 (118.8) |

47.0 (116.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.8 (98.2) |

42.2 (108.0) |

46.9 (116.4) |

47.4 (117.3) |

47.9 (118.2) |

49.0 (120.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 36.4 (97.5) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

35.2 (95.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32.3 (90.1) |

35.0 (95.0) |

36.3 (97.3) |

36.6 (97.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

3.2 (37.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 62.8 (2.47) |

91.3 (3.59) |

47.8 (1.88) |

21.9 (0.86) |

27.7 (1.09) |

23.5 (0.93) |

11.0 (0.43) |

4.8 (0.19) |

1.2 (0.05) |

1.0 (0.04) |

2.5 (0.10) |

19.0 (0.75) |

314.5 (12.38) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.1 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 32.3 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 51 | 53 | 45 | 37 | 36 | 35 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 35 | 39 | 45 | 39 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Wyndham (Köppen BSh/Aw) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 44.7 (112.5) |

44.0 (111.2) |

43.6 (110.5) |

41.6 (106.9) |

38.8 (101.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

37.6 (99.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

41.7 (107.1) |

45.0 (113.0) |

46.0 (114.8) |

45.4 (113.7) |

46.0 (114.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 36.9 (98.4) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.8 (96.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

39.4 (102.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

35.6 (96.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 31.6 (88.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.1 (79.0) |

29.7 (85.5) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

32.6 (90.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 26.3 (79.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.5 (50.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 185.7 (7.31) |

210.1 (8.27) |

158.6 (6.24) |

36.0 (1.42) |

8.4 (0.33) |

3.9 (0.15) |

3.1 (0.12) |

0.0 (0.0) |

4.0 (0.16) |

22.7 (0.89) |

56.4 (2.22) |

156.1 (6.15) |

845 (33.26) |

| Average rainy days | 14.4 | 14.9 | 11.0 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 11.2 | 66.4 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 50 | 53 | 47 | 34 | 29 | 26 | 24 | 24 | 27 | 31 | 36 | 43 | 35 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology | |||||||||||||

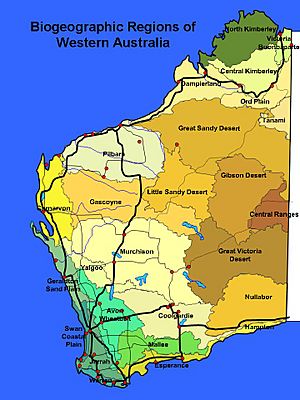

Natural Regions of Western Australia

Western Australia is divided into 25 natural regions. These are part of a larger system called the IBRA system. This system was created to help decide which areas needed protection. The goal was to make sure that different types of natural areas were saved in national parks and nature reserves.

The IBRA system helped identify:

- Which natural areas were already protected.

- Any gaps in the protected areas.

- Main threats to each region.

- Which regions needed more protection urgently.

In Western Australia, this led to some small changes in how regions were defined. For example, parts of the Carnarvon area were added to the Geraldton Sandplain region.

The Avon Wheatbelt This area has old flat lands that have been cut by rivers. It has low hills and plains. You can find unique scrub plants here. Woodlands with different types of eucalyptus trees are also common. Much of this area has been cleared for farming. A big problem here is dry-land salinity, where salt comes to the surface.

The Carnarvon Region This region has sand, soil, and marine sediments. You'll see salty plains with salt-loving plants and low shrubs. There are also woodlands on sandy ridges and plains. Some areas have snake-wood scrubs on clay flats. Along the coast, there are large tidal flats with mangrove trees.

The Coolgardie Region This region is known for its granite rocks and old greenstone belts. It has no main rivers, only closed drainage systems. You can find mallee trees and scrubs on sandy plains and near granite outcrops. There are also many types of eucalyptus woodlands on low hills and plains. The western part has unique proteaceae shrubs, while the east has many acacia trees.

The Central Ranges This region has many old mountain ranges and soil plains. Red sandplains are also common. The sandplains have open woodlands of Desert Oak or Mulga trees over hummock grasses. The ranges have mixed wattle scrubs or cypress pine woodlands.

Dampierland This region has four main types of land. It has sandy plains with a type of scrub called Pindan. Coastal plains have mangroves and salt-loving grasses. River plains have tree savannas with different grasses and eucalyptus trees. The northern and eastern parts have limestone reefs with sparse trees and hummock grasses.

The Esperance Plains This area has scrub and mallee heaths on sandy plains. It's very rich in unique plant species. You'll find herb fields and heaths on granite and quartzite ranges that rise from the plains. Eucalyptus woodlands grow in valleys and on the lower slopes.

The Gascoyne This region has rugged, low mountain ranges and wide, flat valleys. Open mulga woodlands grow on the plains. Mulga scrub and Eremophila shrubs are found on the stony hills. In the east, there are many salt lakes with succulent plants.

The Gibson Desert The Gibson Desert is an elevated flat area with old sandstones. It has mulga parkland over hummock grasses on flat plains. Mixed shrublands with acacia, hakea, and grevillea trees grow on red sand plains and dunes. Older elevated areas have shrublands in the north and mulga scrub in the south. River gum woodlands grow along old riverbeds.

The Geraldton Sandplain This region is very rich in different types of plants. It mainly has proteaceous scrub-heaths on sandy soils. These plants are unique to the area. Large woodlands of York Gum and Jam trees are found on plains near drainage areas.

The Great Sandy Desert This desert is mostly a tree steppe, becoming shrub steppe in the south. It has open hummock grasslands with scattered trees like Owenia reticulata and Bloodwoods. Shrubs like acacia and grevillea grow on red sand dunes. Casuarina decaisneana (Desert Oak) is found in the far east. Elevated areas have shrublands over hummock grasses. Salt lake chains with salt-loving shrubs are also common.

The Great Victoria Desert This is a very dry desert with deep sand dunes. Between the sand dunes, there are tree steppes of Eucalyptus gongylocarpa, Mulga, and Eucalyptus youngiana over hummock grasslands.

The Hampton Region This region has coastal sand dunes on a plain, backed by a limestone cliff. Mallee communities grow on the limestone slopes and sandy areas. Plains below the cliff have eucalyptus woodlands and low myall woodlands.

The Jarrah Woodlands This area has a hard crust on its surface. It's known for its jarrah and marri forests on gravelly soils. In the eastern part, there are marri-wandoo woodlands on clay soils. This area has been heavily logged for timber, so much of the jarrah forest here is new growth.

The Little Sandy Desert This region has red sand dunes and sharp sandstone ranges. It has shrub steppes with acacias, thryptomene, and grevilleas over hummock grasses on sandy areas. Sparse shrub-steppe grows on stony hills. River gum communities and grasslands are found along riverbeds.

The Mallee Region This region has been changed to include an area with Salmon Gum and Black Morrell woodlands. It's a gently rolling area with some blocked drainage. The main plants are mallee trees over heaths on sandy soils over clay. Melaleuca shrubs grow along rivers, and salt-loving shrubs are found on salty plains.

The Murchison This is a dry region with low mulga woodlands. It often has many short-lived plants that appear after rain. Hummock grasslands grow on sandplains. Saltbush shrubs are found on chalky soils, and salt-loving shrubs on salty plains. Red sandplains in the east have mallee-mulga parkland over hummock grasslands.

The Northern Kimberley This region has a plateau with savanna woodlands of Woolybutt and Darwin Stringybark over tall sorghum grasses. Savanna woodlands also grow on volcanic soils. Forests of paperbark trees and pandanus grow along rivers. Large mangrove areas are found in estuaries. Many small patches of monsoon rainforest are scattered throughout the area.

The Nullarbor The Nullarbor is a flat limestone plain with dry cave features. Bluebush and Saltbush steppes are common in the central areas. Low open woodlands of Myall over bluebush are found in the outer areas.

The Ord Victoria Plains This region has flat to gently rolling plains with scattered hills. Grasslands with scattered Bloodwood and Snappy Gum trees are common. The climate is dry, hot, and tropical with semi-arid summer rainfall. The region has three main parts:

- Sandstone ranges and hills with shallow sandy soils supporting hummock grasslands and sparse low trees.

- Volcanic and limestone plains with short grasses on dry soils and medium-height grasslands on cracking clays. River gum forests grow along rivers.

- In the southwest, there are elevated sandplains with sparse trees.

The Pilbara The Pilbara region has four main parts:

- Hamersley: A mountainous area with mulga low woodland over bunch grasses on fine soils. Snappy Gum over hummock grasses grows on the rocky soils of the ranges.

- The Fortescue Plains: This area has river plains. Salt marsh, mulga-bunch grass, and short grass communities are found on the plains. River Gum woodlands grow along the rivers. This is the northernmost point where mulga trees grow.

- Chichester: Granite and basalt plains support shrub steppes with acacia over hummock grasses. Snappy Gum tree steppes grow on the ranges.

- Roebourne: River plains have grass savannas and dwarf shrub steppes. Samphire, Sporobolus, and Mangal grow on marine flats.

The Swan Coastal Plain This is one of the most affected natural areas in the state. It's a low coastal plain, mostly covered with Tuart and Banksia woodlands. Banksia or Tuart trees grow on sandy soils. Paperbark trees grow in many former swampy areas. In the east, the plain rises to older sediments covered by jarrah woodland.

The Tanami The Tanami region mainly has red sandplains. These plains support mixed shrub steppes with Hakea suberea, desert bloodwoods, acacias, and grevilleas over hummock grasslands. Wattle scrub over hummock grasses grows on the ranges. Alluvial and chalky deposits are found throughout. In the north, they are associated with the Sturt Creek drainage, supporting short-grasslands.

The Victoria Bonaparte This region has marine sediments supporting Samphire and Sporobolus grasslands and mangroves. It also has red earth plains and black soil plains with open savannas of tall grasses. Limestone outcrops in the west support tree steppe and vine thicket. Plateaus and sharp ranges of sandstone are found in the south and east. In the southeast, there are gently sloping floodplains supporting low Melaleuca minutifolia woodlands over annual sorghums.

The Warren The Warren region has hilly country with a wet Mediterranean climate. Loamy soils support karri forest. Laterite soils support jarrah-marri forest. Leached sandy soils in low areas and plains support paperbark-sedge swamps. Recent coastal sand dunes are covered with Agonis flexuosa woodlands.

The Yalgoo Region This region is a transition zone between the southwestern and Murchison regions. It has low woodlands of Eucalyptus, Acacia, and Callitris on red sandy plains. The climate is semi-arid to arid, warm, and Mediterranean. Mulga, Callitris- Eucalyptus salubris, and Bowgada open woodlands and scrubs are common. It's rich in short-lived plants.

People and Places

Aboriginal Land Practices

The environment of Western Australia was shaped by the Aboriginal people. Groups like the Noongar, Yamatji, Wangai, Ngaanyatjarra, and Kimberley cultures used practices like firestick farming. This involved carefully burning small areas of land. This returned important nutrients to the soil and helped native plants grow. It also increased the amount of food available for native animals. This practice reshaped Western Australia over 70,000 years.

Many places that later became European settlements were long-time Aboriginal meeting or camping grounds. Major roads also followed Aboriginal trade routes and hunting trails. Aboriginal guides helped European explorers find important water sources.

Sadly, these water sources were often fenced off for sheep and cattle farms. Local Aboriginal groups were then kept out. Trees were cleared, and native animals were hunted. However, many Aboriginal people later found jobs as shepherds or domestic helpers in the new European economy.

Today, Europeans mostly live on lands with wet, mild climates. In drier areas, where farming was common, Aboriginal people were able to keep their connection to their traditional lands much more. In very dry areas, European settlements didn't develop much. Traditional hunting and gathering continued there until more recent times.

European Settlement History

In 1827, Major Edmund Lockyer and Captain James Stirling explored the Dutch-claimed territory. Two years later, Captain Charles Fremantle officially claimed the west coast of New Holland for King George IV.

Stirling and the Swan River Company then set up three easily protected settlements. Perth became the capital, Fremantle was the port, and Guildford was for farming. Other towns like Australind, Bunbury, and Augusta were also chosen because they were easy to defend and reach by boat. Early settlers wanted land near the sea or rivers for easy transport. So, the first land grants were long and narrow, stretching from the rivers.

As British settlements grew, Aboriginal people were gradually pushed off their traditional lands. Even so, the British used Aboriginal tracks to find fresh water. For example, Albany Highway crossed the river at Matta Garrup ("Leg-Deep Place"), which is now the Causeway. It went south to Thomas Peel's lands in Pinjareb country. Other early settlements included Kelmscott and Armadale.

Images for kids

-

Harrisse's map showing different ideas for the Tordesillas Meridian line.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |