History of Christianity in Ireland facts for kids

This article tells the story of Christianity in Ireland. Ireland is an island in the northwest of continental Europe. Today, Ireland is split into two parts: the Republic of Ireland, which covers most of the island, and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom. Most churches in Ireland are organized to cover the whole island. The Roman Catholic Church is the largest religion, with over 73% of people on the island being Catholic.

Contents

- How Christianity Came to Ireland

- Early Missionaries: Palladius and Patrick

- Irish Monasteries and Saints

- Ireland's Famous Learning Centers

- Irish Scholars and Missionaries Abroad

- Arrival of the Vikings

- Anglo-Normans Arrive

- Reformation and Beyond

- Persecution and Penal Laws

- Protestant Ascendancy (1691–1801)

- Ireland's Free State and Republic (1922-Present)

- Vatican II Changes

How Christianity Came to Ireland

Christianity arrived in Ireland even before the 5th century. It likely came through contact with Roman Britain. Christian worship was present in pagan Ireland around 400 CE. Many people think St. Patrick brought Christianity to Ireland, but it was already there before he arrived. Monasteries were built for monks who wanted to live close to God. Places like Skellig Michael show how far they went for peace. Christianity also spread to the Picts and Northumbrians through people like Aidan.

Some people used to talk about a "Celtic Church". But scholars now know this term isn't quite right. It makes it sound like there was one united "Celtic Church" that was against the "Roman Church." This wasn't true. Areas where Celtic languages were spoken were still part of the wider Christian world. They respected the Bishop of Rome just like other places. Some scholars prefer the term "Insular Christianity" to describe the Christian practices that grew up around the Irish Sea.

Early Missionaries: Palladius and Patrick

Palladius was from a noble family in Gaul (modern France). In 429, he was a deacon in Rome. In 431, Pope Celestine I made Palladius a bishop. He sent him to help "Scots believing in Christ" in Ireland. His work mainly focused on Irish Christians in the eastern parts of Ireland. It's not certain if he converted many new people. His mission seems to have been successful, even though later stories about Patrick sometimes made Palladius's work seem less important.

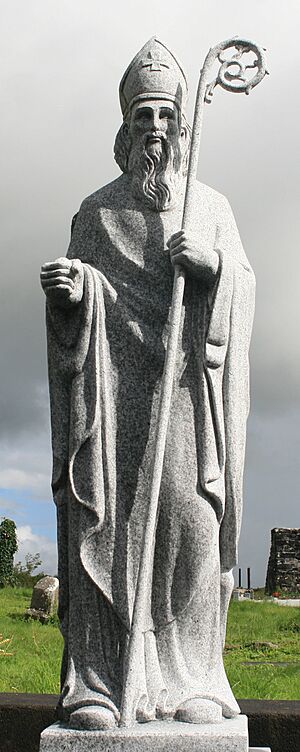

The exact dates for Saint Patrick are not clear. We only know he lived sometime in the fifth century. He was a missionary bishop, meaning he traveled to spread the faith, rather than just serving existing Christians. He seems to have worked in Ulster and north Connacht. However, much of what we know about him comes from unreliable stories written after the seventh century.

Irish Monasteries and Saints

Many monasteries started in Ireland in the sixth century. These included Clonard, founded by St. Finian, and Clonfert by St. Brendan. Other famous ones were Bangor by St. Comgall, Clonmacnoise by St. Kieran, and Glendalough by St. Kevin.

In 563, St. Columba, who was from Donegal, traveled to Caledonia (Scotland). He founded a monastery on the lonely island of Iona.

Ireland's Famous Learning Centers

Monastic schools in Ireland became excellent places for learning for people from all over Europe. Historians like Bede and Aldhelm wrote that many English students came to Ireland to train as missionaries. They wanted to convert their pagan relatives on the European continent. Many of these English monks had successful church careers after their training in Ireland.

Bede and Aldhelm were churchmen, so they focused on religious training. But they both said that Irish monastic schools also taught everyday subjects. Studying the Bible was most important. However, students often traveled between different monasteries to find teachers who knew a lot about other subjects too.

In the early 600s, many Anglo-Saxon nobles were educated in Irish monasteries in northern Britain, especially at Iona. Bede wrote that the Irish welcomed English students. They gave them food, books, and teaching without asking for payment. When these English nobles returned home, they invited Irish missionaries to their pagan kingdoms to spread Christianity. For example, King Oswald invited the Irish bishop Aidan from Iona. Aidan founded the monastery at Lindisfarne in Northumbria around 635. The English historian Bede showed that Irish missionaries were more successful at converting the pagan English in the north than the missionaries sent from Rome to the south of England in 597.

More missionaries arrived from Ireland. The monastery at Iona, with Columba as its leader, quickly grew. From there, the Dalriadian Scots and the Picts (in Scotland) learned about Christianity. When Columba died in 597, Christianity had been preached and accepted in every part of Caledonia and on its western islands. In the next century, Iona was so successful that its abbot, St. Adamnan, wrote a famous book called "Life of St. Columba" in excellent Latin. From Iona, Irish missionaries like Aidan went south to spread Christianity in Northumbria, Mercia, and Essex.

The monastery of Iona encouraged writing in both Latin and Irish. For example, Abbot Adomnán (679–704) wrote a Latin book describing important places in the Holy Land. He also created a law in Irish called "Cáin Adomnáin" (697). This law aimed to protect women, children, and church members during wars.

A Latin hymn, "Exalted Creator," is thought to have been written by Columba, the founder of Iona. Also, three poems praising Columba are among the oldest complete poems in the Irish language. One of them, "Eulogy for Columba," is believed to be from around 600, close to Columba's death in 597.

The monastery at Bangor also created important religious texts in Latin. It also had a lively tradition of Irish stories. In the late seventh century, a collection of beautiful Latin religious poems and hymns, called the "Antiphonary of Bangor," was put together there. Important Irish stories also came from Bangor. "The Voyage of Bran," an early example of an Irish "otherworld voyage," was written at Bangor. It tells of Bran's journey across the ocean and the wonders he found in a perfect otherworld.

Irish Scholars and Missionaries Abroad

Missionaries from Ireland traveled to England and Continental Europe. They spread news of the great learning happening in Ireland. Scholars from other countries came to Irish monasteries. These monasteries were excellent and often isolated. This helped them keep Latin learning alive during the Early Middle Ages. This period also saw a flourishing of Insular art, especially in illuminated manuscripts, metalwork, and sculpture. Famous examples include the Book of Kells, the Ardagh Chalice, and the many carved stone crosses across the island.

These monasteries offered safety to many great scholars and thinkers from Europe. They helped preserve important Latin knowledge for future generations. During this time, Ireland produced amazing illuminated manuscripts. Perhaps the most famous is The Book of Kells, which you can still see at Trinity College, Dublin.

Learning in the West began to revive with the Carolingian Renaissance in the Early Middle Ages. Charlemagne, a powerful emperor, invited scholars from England and Ireland to his court. He also ordered schools to be set up in every abbey in his empire in 787 AD. These schools became centers of medieval learning. During this early period, knowledge of the Greek language had almost disappeared in the West, except in Ireland. There, it was widely known in the monastic schools.

Irish scholars were very important in the Frankish court. They were known for their knowledge. One of them was Johannes Scotus Eriugena, who helped start a new way of thinking called scholasticism. Eriugena was a very important Irish thinker of the early monastic period. He was also a very original philosopher. He knew Greek well and translated many Greek works into Latin. This helped others learn about the ideas of the Cappadocian Fathers and the Greek theological tradition.

Arrival of the Vikings

In the 800s and 900s, groups of Norse warriors, known as Vikings, attacked the countryside. Monasteries were often their favorite targets because they held valuable gold religious items.

As the 700s ended, religion and learning were still strong in Ireland. But new dangers appeared. The Danes from Scandinavia arrived. They were pagans and pirates, and very strong fighters on land and sea.

In Ireland, like other places, they attacked monasteries and churches. They damaged altars and stole gold and silver items. Under local Irish and Christian leaders, churches were destroyed. Church lands were taken by ordinary people, and monastic schools were left empty. Lay abbots (non-religious leaders) took charge in places like Armagh. Bishops were appointed without proper church areas and gave out religious orders for money. There was a lot of confusion in church leadership and corruption everywhere.

A series of church meetings, starting with the Rathbreasail in 1118, tried to fix these problems. At these meetings, important rules were made. For the first time, a system of diocesan bishops (bishops in charge of specific areas) was set up. Meanwhile, St. Malachy, the Archbishop of Armagh, did great work in his own area and beyond. His early death in 1148 was a big setback for church reform. But so many problems couldn't be fixed by one person or in one lifetime. Despite his efforts, the rules from the meetings were often ignored, and the new church boundaries were not followed.

Anglo-Normans Arrive

In December 1154, Henry Plantagenet became Henry II, King of England. In the same month, an Englishman, Nicholas Breakspeare, became Pope. Henry wanted to make sure that civil laws and courts were more powerful than church laws and courts. In 1155, Henry got a special letter from Pope Adrian IV called Laudabiliter. This letter allowed Henry to conquer Ireland. The Pope said Henry should go to Ireland "to stop wickedness, to improve bad behavior, and to plant good values." In return, Henry had to promise to pay a penny each year from every house to the Pope (this was called Peter's Pence).

Henry's invasion was put on hold while he dealt with other issues. He continued to fight against the Church's power, and against Thomas à Beckett in England. In 1166, Henry decided to help an Irish king from Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, get his land back. The first group of Norman invaders came to Ireland in 1169. A stronger force led by Strongbow (Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke) followed in 1170. In 1171, Henry himself landed in Waterford and went to Dublin. There, most of the Irish chiefs agreed to accept his rule. This agreement was written down in the Treaty of Windsor 1175.

Reformation and Beyond

It took until the late 1600s for the English Crown to fully control Ireland. This happened through a series of wars between 1534 and 1691. During this time, English and Scottish Protestant settlers moved to Ireland. However, most of the Irish people remained Roman Catholic.

Henry VIII and the Church

Henry VIII wanted to break the power of the old Anglo-Norman kings and take control of Ireland. As he did this, he put English lords in charge of land he took. He also took wealth from Catholic monasteries and churches, just as he had done in England. In 1536, during the Reformation, Henry arranged for the Irish Parliament to declare him head of the Church in Ireland. When the Church of England was reformed under Edward VI, the Church of Ireland was also changed.

At the start of his rule, Henry VIII was busy with problems in England and Europe. So, he didn't pay much attention to Ireland. It was only after 25 years that he focused on Ireland. This was mainly because of his conflict with the Church over his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Then, the Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This law gave Henry spiritual power over England and made him head of the Church of England instead of the Pope. When church officials in Ireland refused to agree, Henry took away their voting rights. He also took church lands and closed monasteries. In some cases, monks were killed; in others, they were left homeless and poor.

Elizabeth I and Religious Change

Queen Elizabeth I worried about Ireland's Catholicism. She also knew Ireland could be a strategic place for her enemies. So, she strengthened English power in Ireland.

The official church in Ireland became more strictly Calvinist than the Church in England. James Ussher, who later became Archbishop of Armagh, wrote the Irish Articles. These were adopted in 1615. In 1634, the Irish Convocation (a church assembly) adopted the English Thirty-Nine Articles along with the Irish Articles. After 1660, the Thirty-Nine Articles became more important. They are still the official beliefs of the Church of Ireland today.

The English-speaking minority mostly belonged to the Church of Ireland or to Presbyterianism. But the Irish-speaking majority stayed loyal to the Roman Catholic Church. From this time on, religious conflict became a common problem in Irish history.

Translating the Bible into Irish

The first Irish translation of the New Testament was started by Nicholas Walsh, the Bishop of Ossory. He worked on it until he was killed in 1585. His assistant, John Kearny, and Nehemiah Donellan, the Archbishop of Tuam, continued the work. It was finally finished by William O'Domhnuill (William Daniell), who became Archbishop of Tuam after Donellan. Their work was printed in 1602.

The Old Testament was translated by William Bedel (1571–1642), the Bishop of Kilmore. He finished his translation during the reign of Charles I. However, it was not published until 1680 in a revised version by Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713), Archbishop of Dublin. William Bedell had also translated the Book of Common Prayer in 1606. An Irish translation of the updated prayer book of 1662 was done by John Richardson (1664–1747) and published in 1712.

The first full Bible translation approved by the Catholic Church was An Bíobla Naofa. It was overseen by Pádraig Ó Fiannachta at Maynooth and published in 1981.

Persecution and Penal Laws

The Irish Confederate Wars caused a lot of damage to church property. Irish Catholics faced harsh treatment under Oliver Cromwell. Their situation only slightly improved under the Stuart kings. After these wars and the defeat of James II in 1691, Irish Catholic landowners lost most of their land. The new Penal Laws made it even harder to practice Roman Catholicism. Many priests and bishops had to hide or leave the country. The religious situation only started to get better in the 1770s.

Protestant Ascendancy (1691–1801)

Before the Stuart kings, Ireland had thirty-four boroughs (towns with special rights). In 1613, forty new boroughs were created, all controlled by Protestants. This meant that the Catholic majority in the Irish Parliament became a minority. By the end of the 1600s, all Catholics, who made up about 85% of Ireland's population, were banned from the Irish Parliament. As a result, political power was completely in the hands of a British Protestant minority, mostly Anglican. The Catholic population suffered greatly from severe political and economic restrictions.

By the late 1700s, many of the Anglo-Irish ruling class began to see Ireland as their home country. A group in Parliament led by Henry Grattan pushed for better trade with England. They also wanted more independence for the Parliament of Ireland. However, reforms in Ireland stopped when it came to allowing Irish Catholics to vote. This was finally allowed in 1793. But Catholics still could not enter Parliament or become government officials.

The Oath of Allegiance and Penal Laws

The Treaty of Limerick pardoned Catholic soldiers of King James. It protected their lands and allowed them to leave the country if they wished. All Catholics could take an oath of loyalty instead of an oath of supremacy. They were also supposed to have the same rights as they did under Charles II. King William also promised that the Irish Parliament would ease the penal laws. However, this treaty was soon broken. Despite William's pleas, the Irish Parliament refused to approve it and passed new penal laws.

Under these new laws, Catholics were excluded from Parliament, from being judges or lawyers, from the army and navy, and from all government jobs. They couldn't be part of town councils or even live in corporate towns. They couldn't have Catholic schools at home or attend foreign schools. They couldn't inherit land or hold land under lease. They couldn't have weapons or a horse worth more than £5. They couldn't bury their dead in Catholic ruins or go on pilgrimages to holy wells. They also couldn't observe Catholic holidays.

Catholics could not marry Protestants. A clergyman helping such a marriage could be put to death. If a Catholic landlord's wife became Protestant, she got separate money. If a son became Protestant, he got the whole estate. If a Catholic landlord only had Catholic children, his estate had to be divided equally among them after his death. All regular clergy (monks, friars) and bishops had to leave the kingdom. Secular clergy (parish priests) could stay, but they had to be registered. Their churches couldn't have steeples or bells.

In 1728, Catholics outnumbered Protestants 5 to 1. A few Catholics managed to keep their lands with the help of Protestant friends. But most gradually became poor farmers or day-laborers. Their standard of living dropped far below what they were used to. Many Catholics chose to move away, hoping to find a better life elsewhere.

Irish Parliament and Growing Tolerance

In the Irish Parliament, a desire for independence grew. In 1496, Poynings' Law was passed. This law said that the Irish Parliament could not meet or propose any laws without first getting permission from both the Irish and English Privy Councils. Also, the English Parliament claimed the right to make laws for Ireland. They showed this by passing laws that stopped Irish cattle (1665) and Irish wool (1698) from being imported. They also passed a law about Irish lands that had been taken (1700).

When an Irish member, Molyneux, protested, the English Parliament condemned him. They ordered his book to be burned. In 1719, they passed a law that clearly stated they had the power to make laws for Ireland. This law also took away the power of the Irish House of Lords to hear appeals. The fight by Swift against Wood's halfpence showed that Molyneux's spirit was still alive. Lucas continued the fight, and Grattan gained legislative independence for Ireland in 1782.

In 1778, a law allowed Catholics to hold all lands under lease. In 1782, another law allowed them to build Catholic schools (with permission from the Protestant bishop). They could also own a horse worth more than £5 and attend Mass without being forced to report the priest. Catholic bishops were no longer forced to leave the kingdom, and Catholic children were not specially rewarded for becoming Protestant.

It took ten more years for further changes. Then, a law was passed allowing Catholics to build schools without Protestant permission. It also allowed Catholics to become lawyers and made marriages between Protestants and Catholics legal. Much more important was the Act of 1793. This law gave Catholics the right to vote in Parliament and local elections. It also allowed them into universities and civil and military jobs. All restrictions on land ownership were removed. However, they were still kept out of Parliament, from being senior lawyers, and from a few higher civil and military jobs.

Grattan always supported religious freedom. He wanted to get rid of all the Penal Laws. But in 1782, he mistakenly thought his work was done when Ireland gained legislative independence. He forgot that the government leaders were still independent of the Irish Parliament. They only answered to the English government. Also, with "rotten boroughs" controlled by a few rich families, very few people could vote in the counties. Many seats were filled by people who received payments or jobs from the government. This made the Irish Parliament a joke.

Like Grattan, Flood and Charlemont wanted to reform Parliament. But unlike him, they were against giving more rights to Catholics. Foster and Fitzgibbon, who led the forces of corruption and prejudice, opposed every attempt at reform. They only agreed to the Act of 1793 because of strong pressure from Pitt and Dundas. These English ministers were worried about the ideas of the French Revolution spreading in Ireland. They feared a foreign invasion and wanted to keep Catholics happy.

In 1795, more changes seemed likely. A new, more liberal viceroy, Lord Fitzwilliam, was appointed. He believed Pitt wanted Catholic rights to be granted. He immediately removed a greedy official named Beresford, who was so powerful he was called the "King of Ireland." Fitzwilliam refused to consult the Lord Chancellor Fitzgibbon or Foster, the Speaker. He trusted Grattan and Ponsonby. He said he would support Grattan's bill to let Catholics into Parliament.

The high hopes raised by these events were crushed when Fitzwilliam was suddenly recalled. This happened even though he had been allowed to go so far without any protest from Portland, the home secretary, or from Pitt. Pitt disliked the Irish Parliament because it had rejected his trade proposals in 1785 and disagreed with him in 1789. He was already planning to unite the parliaments of Britain and Ireland. He felt that letting Catholics into Parliament would stop his plans. He was probably also influenced by Beresford, who had powerful friends in England. And by the king, whom Fitzgibbon had wrongly convinced that allowing Catholics into Parliament would break his coronation oath. Other reasons likely contributed to this sudden and terrible change. It filled Catholic Ireland with sadness and the whole nation with dismay.

The new viceroy, Lord Camden, was told to make Catholic bishops happy by setting up a Catholic college to train Irish priests. This led to the establishment of Maynooth College. But he was also told to oppose all parliamentary reform and all Catholic rights. He did these things eagerly. He immediately gave Beresford his job back and restored Foster and Fitzgibbon to favor, with Fitzgibbon becoming Earl of Clare. He also successfully stirred up old religious hatreds. This led to the Ulster groups, the Protestant "Peep-of-Day Boys" and the Catholic "Defenders", becoming more bitter. The Defenders turned to republican and revolutionary ideas and joined the United Irish Society. The Peep-of-Day Boys joined the recently formed Orange Society. This group took its name from William of Orange and fought for Protestant power and against Catholicism.

These rival groups spread from Ulster to other parts of Ireland, bringing religious conflict. Instead of stopping both, the government sided with the Orangemen. Their illegal actions were ignored, while Catholics were hunted down. Laws like the Arms' Act, Insurrection Act, and Indemnity Act, along with suspending the Habeas Corpus Act, put Catholics outside the protection of the law. Undisciplined soldiers, many from the Orange lodges, were then let loose among them. This led to martial law, forced housing of soldiers, flogging, picketing, half-hanging, destruction of Catholic property and lives, and attacks on women. Eventually, Catholic anger exploded. Then Wexford rose in rebellion. Looking back, it seems certain that if Hoche had landed at Bantry in 1796, or even a small force had landed at Wexford in 1798, or a few other counties had shown the bravery of Wexford, English power in Ireland would have been destroyed, at least for a while. But one county could not fight the British Empire, and the rebellion was quickly put down with much bloodshed.

Camden was replaced by Lord Cornwallis. He came to Ireland specifically to bring about a Legislative Union between Britain and Ireland. Foster refused to support him and joined the opposition. However, Fitzgibbon helped Cornwallis, as did Castlereagh. Castlereagh had been acting as chief secretary and was now officially appointed. Then began one of the most shameful periods in Irish history. Even the corrupt Irish Parliament was unwilling to vote away its own existence. In 1799, the opposition was too strong for Castlereagh. But Pitt told him to keep trying, and the great struggle continued.

On one side were powerful speakers, patriotism, and public virtue: Grattan, Plunket, Bushe, Foster, Fitzgerald, Ponsonby, and Moore. This was a truly strong group. On the other side were the less honorable members of Parliament. These were the needy, the wasteful, and those who wanted power. Castlereagh influenced them, using all the resources of the British Empire. Officials who voted against him immediately lost their jobs and pensions. Military officers were denied promotions, and magistrates were removed from their positions. While those against the Union were punished, those who supported it received lavish rewards. Poor people got well-paid jobs with little work. Lawyers with no clients became judges or commissioners. Rich people who wanted social status got noble titles and jobs and pensions for their friends. Owners of "rotten boroughs" received large sums of money for their interests. Catholics were promised the right to be in a united Parliament. As a result, many bishops, some clergy, and a few ordinary Catholics supported the Union. They didn't mind ending an assembly as prejudiced and corrupt as the Irish Parliament. Through these methods, Castlereagh succeeded. In 1801, the United Parliament of Great Britain and Ireland opened its doors.

Catholic Emancipation

The next 25 years were a time of unfulfilled hope. Dr. Troy, the Archbishop of Dublin, strongly supported the Union. He convinced nine other bishops to agree to the government having a say in appointing bishops. This was common in European monarchies. In return, he wanted Emancipation (full rights for Catholics) linked with the Union. Castlereagh was open to this. But Pitt was vague in public, though Catholic Unionists were sure he favored linking Catholic rights with the Union. They hoped this would create a completely new system for a United Kingdom.

Disappointment came when nothing was done in the first session of the United Parliament. It grew when Pitt resigned and was replaced by Addington. Cornwallis, however, assured Dr. Troy that Pitt had resigned because he couldn't overcome King George III's refusal. The King believed it went against the Act of Settlement and his coronation oath. Pitt declared he would never take office again if emancipation wasn't granted. Despite this, he became Prime Minister again in 1804. He no longer supported emancipation, having promised never to raise the issue in Parliament during the king's lifetime. He kept this promise. When Fox presented the Catholic petition in 1805, Pitt opposed it.

After 1806, when both Pitt and Fox died, Grattan became the main supporter of Catholics. He entered the British Parliament in 1805. Hoping to win over opponents, he was willing to allow the government to have a say in bishop appointments in 1808. Dr. Troy and higher-ranking Catholics agreed. But other bishops were unwilling. They rejected the offer of state-paid clergy or state-appointed bishops. However, the debate continued for many years. This distracted Catholic plans and weakened their efforts. More problems arose in 1814 when Quarantotti, a church official, issued a statement favoring the government's say in appointments. However, he acted beyond his authority because Pius VII was in France. When the Pope returned to Rome, the statement was rejected.

During these years, Catholics badly needed a leader. John Keogh, the strong leader of 1793, was old. Others like Lords Fingall and Gormanstone were not strong enough to deal with the big problems. A more skilled and energetic leader was needed, someone with less faith in petitions and loyalty promises. Such a leader was found in Daniel O'Connell. He was a Catholic lawyer whose first public appearance in 1800 was against the Union. He was a great lawyer and speaker, with endless courage. He played a big part in Catholic committees. From 1810, he was the most respected Catholic leader.

Yet, the Catholic cause moved slowly. When Grattan died in 1820, emancipation had not happened. The House of Lords also rejected Plunket's Bill of 1821, even though it passed the House of Commons and allowed the government to have a say in bishop appointments. Finally, O'Connell decided to rally the people. In 1823, with the help of Richard Lalor Sheil, he founded the Catholic Association. Its progress was slow at first, but it gradually grew stronger. Dr. Murray, the new Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, joined it. So did Dr. Doyle, the great Bishop of Kildare. Other bishops followed, and then the clergy and people joined too.

This created a large national organization. It had a central office in Dublin and smaller groups in every parish. It was supported by a "Catholic rent" (small payments from members). It watched over local and national issues. As Mr. Canning described it, it performed "all the functions of a regular government, and had obtained complete control over the masses of the Irish people." The Association was banned in 1825 by an Act of Parliament. But O'Connell simply changed its name. The New Catholic Association, with its New Catholic rent, continued the protests as before.

And there was more. The Catholic Relief Act of 1793 gave the right to vote to "forty-shilling freeholders" (small landowners). These freeholders were usually controlled by their landlords. But now, protected by a powerful association and encouraged by priests and O'Connell, the freeholders broke free. In Waterford, Louth, Meath, and other places, they voted for the candidates chosen by the Catholic Association in elections. They humbled the landlords. They even elected O'Connell himself for Clare in 1828. The Tory ministers, Wellington and Peel, then guided the Catholic Relief Bill of 1829 through Parliament.

However, the forty-shilling freeholders temporarily lost their right to vote. The new law also kept Catholics out of some higher civil and military jobs. It stopped priests from wearing religious clothes outside churches and bishops from using the titles of their church areas. It also prevented clergy from getting money from charitable gifts. In other ways, Roman Catholics in the UK were given the same rights as other religions. At last, they were fully included in the benefits of the constitution.

Irish Catholics still had several complaints: the official state Church, landlordism, and unequal education. Mr. Gladstone started with the Church of Ireland. He introduced a bill to take away its official status and funding. Commissioners were appointed to close it down and manage its property, which was worth over £15,000,000. Of this, £11,000,000 was given to the disestablished Church. Some went to current office holders, and some helped the Church continue its work. Nearly £1,000,000 was divided between Maynooth College (which lost its yearly grant) and the Presbyterian Church (which lost its Regium Donum - a royal grant). The Presbyterian Church got twice as much as Maynooth. Any extra money was to be used by Parliament for public projects.

Ireland's Free State and Republic (1922-Present)

The Roman Catholic Church has had a strong influence on the Irish state since it began in 1922. However, that influence has become less powerful in recent years.

When Ireland was divided in 1922, 92.6% of the Free State's population was Catholic, while 7.4% was Protestant. By the 1960s, the Protestant population had dropped by half. Many people left the country because of a lack of jobs. But the rate of Protestant emigration was much higher. Many Protestants left in the early 1920s. Some felt unwelcome in a mostly Catholic and nationalist state. Others were afraid because Protestant homes were burned by republicans during the civil war. Some saw themselves as British and didn't want to live in an independent Irish state. Economic problems caused by the recent violence also played a role. The Catholic Church also had a rule, called Ne Temere, which said that children of marriages between Catholics and Protestants had to be raised as Catholics.

Vatican II Changes

In both parts of Ireland, Church rules and practices changed a lot after the Vatican II reforms in 1962. Probably the biggest change was that Mass could be said in local languages instead of only Latin. In 1981, the Church ordered its first edition of the Bible in the Irish language.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |