History of Miami facts for kids

Thousands of years before Europeans arrived, the area where Miami, Florida is today was home to the Tequesta people. This Native American tribe lived along Florida's southeastern Atlantic coast. They didn't have much contact with Europeans and mostly left the area by the mid-1700s. Miami gets its name from the Mayaimi tribe, who lived near Lake Okeechobee until the 1600s or 1700s.

In 1566, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés came from Spain to remove the French from Florida. He left two Jesuit missionaries to teach the Tequesta about Roman Catholicism, but the tribe wasn't interested. The missionaries returned to St. Augustine after a year. Later, Fort Dallas was built in 1836 and used as a military base during the Second Seminole War.

In its early days, the Miami area was known as "Biscayne Bay Country." People described it as a wild but promising place, one of Florida's best spots for building. After a big freeze in 1894, Miami's crops were the only ones in Florida that survived. This led Julia Tuttle, a local landowner, to convince Henry Flagler, a railroad owner, to extend his Florida East Coast Railway to Miami. On July 28, 1896, Miami officially became a city with just over 300 people.

Miami grew quickly in the 1920s. However, this growth slowed when the real estate market crashed in 1925. Soon after, the Great Miami Hurricane hit in 1926, and then the Great Depression started in the 1930s. When World War II began, Miami was important in fighting German submarines because of its location. The war helped Miami's population grow to almost half a million. After Fidel Castro took power in 1959, many Cubans moved to Miami, increasing the population even more. In the 1980s and 1990s, South Florida faced challenges like riots, economic issues, Hurricane Andrew, and the Elián González affair. Despite these, Miami is still a major international city for business and culture.

Contents

Early Life in Miami

The first signs of Native American life in the Miami area date back about 10,000 years. The region had many pine forests and was full of deer, bears, and wild birds. These early people settled along the Miami River, with their main villages on the north side. They made various weapons and tools from shells.

When Europeans first arrived in the mid-1500s, the Tequesta people lived in the Miami area. They controlled a large part of southeastern Florida, including what is now Miami-Dade, Broward, and southern Palm Beach counties. The Tequesta fished, hunted, and gathered plants for food. They did not farm. They buried small bones of the dead but kept larger bones in a box for the village to see. The Tequesta are known for creating the Miami Circle, a mysterious ancient site.

Spanish Arrivals (1500s-1700s)

In 1513, Juan Ponce de León was the first European to visit the Miami area. He sailed into Biscayne Bay and wrote about a place called Chequescha, which was Miami's first recorded name. It's not known if he landed or met the natives.

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and his men made the first recorded landing in 1566. They visited the Tequesta settlement while looking for Menéndez's son. A year later, Spanish soldiers and Father Francisco Villareal built a Jesuit mission at the mouth of the Miami River, but it didn't last long. By 1570, the Jesuits left Florida. After the Spanish left, the Tequesta Indians suffered from European diseases like smallpox. Wars with other tribes also weakened them. By 1711, the Tequesta asked to move to Havana, Cuba. The Cubans sent ships, but Spanish illnesses killed most of the Tequesta. In 1743, the Spanish sent another mission to Biscayne Bay, building a fort and church. But the mission was soon closed.

Non-Spanish Settlers (1700s-1800s)

In 1766, Samuel Touchett received a land grant of 20,000 acres (81 km²) in the Miami area from the British government. He wanted to start a plantation but had money problems and couldn't develop the land.

The first permanent white settlers arrived around 1800. Pedro Fornells, from Minorca, moved to Key Biscayne to claim his land grant. He left a caretaker there when he returned to St. Augustine. In 1803, Fornells noticed squatters on the mainland across Biscayne Bay. Bahamian squatters had settled along the coast since the 1790s. Several families, including the Egans and Lewises, received land grants from the U.S. government in what is now Miami.

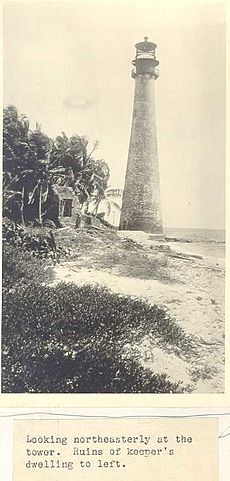

Treasure hunters from the Bahamas and the Keys came to South Florida looking for treasure from shipwrecks. Some accepted Spanish land offers along the Miami River. Around the same time, Seminole Indians and runaway slaves also arrived. In 1825, the Cape Florida Lighthouse was built on nearby Key Biscayne to warn ships about dangerous reefs.

In 1830, Richard Fitzpatrick bought land on the Miami River. He built a plantation using slave labor, growing sugarcane, bananas, and tropical fruit. In January 1836, at the start of the Second Seminole War, Fitzpatrick moved his slaves and closed his plantation.

The Second Seminole War greatly affected the area. Fort Dallas was located on Fitzpatrick’s plantation. Most non-Indian people were soldiers stationed there. This war was very destructive for the native population in Miami. The Cape Florida lighthouse was burned by Seminoles in 1836 and wasn't fixed until 1846.

After the war ended in 1842, Fitzpatrick’s nephew, William English, reopened the plantation. He planned the "Village of Miami" on the south bank of the Miami River and sold land plots. When English died in 1852, his plantation closed.

The Miami River gave its name to the growing town, which came from the Mayaimi Indian tribe. In 1844, Miami became the county seat. Six years later, a census showed 96 people living there. The Third Seminole War (1855-1858) was less destructive but still slowed settlement. After the war, some soldiers stayed, and some Seminoles remained in the Everglades.

From 1858 to 1896, only a few families lived in the Miami area, in small settlements along Biscayne Bay. The first settlement was at the mouth of the Miami River, called Miami, Miamuh, or Fort Dallas. The Brickell family was important here. William Brickell and his wife, Mary, bought land on the south bank of the river in 1870. They ran a trading post and post office there for the rest of the 1800s.

Other settlements within Miami's future city limits included Lemon City (now Little Haiti) and Coconut Grove. Many settlers were homesteaders, attracted by offers of 160 acres (0.65 km²) of free land from the U.S. government.

Rapid Growth and City Formation (1890s)

In 1891, Julia Tuttle moved to South Florida after her husband died. Despite money problems, she bought 640 acres (2.6 km²) on the north bank of the Miami River, where downtown Miami is today.

She tried to convince railroad owner Henry Flagler to extend his Florida East Coast Railway south to Miami, but he first said no. In December 1894, a freeze destroyed almost all citrus crops in northern Florida. A few months later, on February 7, 1895, another freeze hit, wiping out the remaining crops. Unlike most of Florida, the Miami area was not affected. Tuttle wrote to Flagler again, asking him to visit. Flagler sent James E. Ingraham to check, and he returned with a good report and orange blossoms to show Miami had escaped the frost. Flagler then visited himself and decided the area was ready for growth. He chose to extend his railroad to Miami and build a resort hotel.

On April 22, 1895, Flagler wrote to Tuttle, confirming her offer of land in exchange for the railroad, a city plan, and a hotel. Tuttle would give Flagler 100 acres (0.40 km²) for the city. Flagler made a similar agreement with William and Mary Brickell for their land.

Even before the railroad extension was announced, rumors spread, causing real estate activity in Biscayne Bay. The news was officially announced on June 21, 1895. In late September, railroad construction began, and settlers started arriving in the "freeze proof" lands. On October 24, 1895, Flagler and Tuttle's contract was approved.

With the railroad being built, Miami became busy. Men from all over Florida came to Miami, waiting for Flagler to hire workers for the hotel and city. By late December 1895, 75 men were clearing the hotel site. They lived in tents and huts in the wilderness, which had no streets. Many of these men had lost money and work due to the freeze.

On February 1, 1896, Tuttle gave Flagler two deeds for his hotel land and the 100 acres (0.40 km²) for the city. The land titles had to be checked before lots could be sold. On March 3, Flagler hired John Sewell to start working on the town as more people arrived. On April 7, 1896, the railroad tracks reached Miami, and the first train arrived on April 13. Flagler was on this special train. Regular passenger service began on April 22.

On July 28, 1896, a meeting was held to make Miami a city. Only men living in Miami or Dade County could vote. Joseph A. McDonald, Flagler’s construction chief for the Royal Palm Hotel, led the meeting. After confirming enough voters were present, they voted to create "The City of Miami." John B. Reilly, who led Flagler's land company, was elected the first mayor.

Many residents wanted to name the city "Flagler," but Henry Flagler insisted it not be named after him. So, on July 28, 1896, the City of Miami, named after the Miami River, was officially formed with 502 voters. This included 100 registered black voters, who were the main workforce for building Miami. Land deeds kept black residents in the northwest section of Miami, which became "Colored Town" (now Overtown).

The Twentieth Century

The Magic City (1900s-1930s)

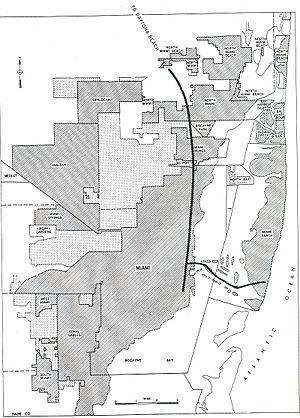

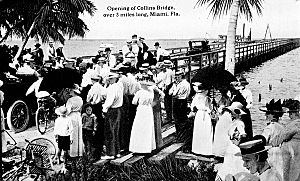

Miami grew very fast until World War II. In 1900, Miami had 1,681 people. By 1910, it had 5,471, and by 1920, 29,549. As thousands moved to the area, more land was needed. The Florida Everglades used to reach within three miles (5 km) of Biscayne Bay. Starting in 1906, canals were built to drain some of this water. Miami Beach was developed in 1913 when a two-mile (3 km) wooden bridge was finished. In the early 1920s, Miami allowed gambling and was relaxed about prohibition. This led thousands of people from the northern U.S. to move to Miami. This caused the Florida land boom of the 1920s, where many tall buildings were constructed. Miami's population doubled from 1920 to 1923. Nearby areas like Lemon City, Coconut Grove, and Allapattah joined Miami in 1925, creating the Greater Miami area.

However, this boom began to slow due to building delays and too many building materials overloading the transport system. On January 10, 1926, a ship called the Prinz Valdemar got stuck and blocked Miami Harbor for almost a month. The three main railway companies then stopped all incoming goods except food. The cost of living became very high, and finding an affordable place to live was almost impossible. This economic bubble was already collapsing when the terrible Great Miami Hurricane hit in 1926, ending the boom. This Category 4 storm was one of the most costly and deadly storms in the U.S. during the 1900s. The Red Cross reported 373 deaths, but other estimates vary. Between 25,000 and 50,000 people in Miami were left homeless. The Great Depression followed, leaving over 16,000 people in Miami jobless. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was opened to help.

In the mid-1930s, the Art Deco district of Miami Beach was built. Also, on February 15, 1933, there was an attempt to assassinate President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. While Roosevelt was giving a speech in Miami's Bayfront Park, Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian anarchist, opened fire. Mayor Anton Cermak of Chicago, who was shaking hands with Roosevelt, was shot and died two weeks later. Four other people were wounded, but Roosevelt was not hurt. Zangara was quickly tried and executed.

World War II (1940s)

By the early 1940s, Miami was still recovering from the Great Depression when World War II began. While many Florida cities faced financial ruin, Miami was not as badly affected. Early in the war, German U-boats attacked American ships, including one sunk near Miami Beach in May 1942. To defend against U-boats, Miami was placed in two military districts.

In February 1942, the Gulf Sea Frontier was created to protect Florida's waters. By June, more attacks forced military leaders to increase ships and men. They also moved their headquarters to Miami, using its location at the southeastern corner of the U.S. As the fight against U-boats grew, more military bases appeared in Miami. The U.S. Navy took over Miami's docks and set up air stations at Opa-locka Airport and Dinner Key. The Air Force also built bases at local airports.

Many military schools, supply stations, and communication centers were also set up. Instead of building large army bases, the Army and Navy used Miami's hotels as barracks, movie theaters as classrooms, and beaches and golf courses as training grounds. Overall, over 500,000 enlisted men and 50,000 officers were trained in South Florida. After the war, many service members returned to Miami, causing the population to reach almost half a million by 1950.

Changes in Miami (1950s-1970s)

First Wave of Cuban Immigrants

After the 1959 Cuban revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power, most Cubans living in Miami returned to Cuba. Soon after, however, many middle and upper-class Cubans moved to Florida with few belongings. Some Miamians, especially African Americans, were concerned, believing Cuban workers were taking their jobs. Schools also struggled to educate thousands of Spanish-speaking Cuban children. Many Miamians, fearing the Cold War would become World War III, left the city or built bomb shelters. Many Cuban refugees realized they wouldn't be returning to Cuba soon. In 1965 alone, 100,000 Cubans arrived on daily "freedom flights" from Havana to Miami. Most settled in the Riverside neighborhood, which became known as "Little Havana". This area became a mostly Spanish-speaking community. By the end of the 1960s, over 400,000 Cuban refugees lived in Miami-Dade County.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a special permission called "parole" allowed Cubans to enter the U.S. To let them stay permanently, the Cuban Adjustment Act was passed in 1966. This act allowed Cubans who arrived after 1959 and had been in the U.S. for at least a year to become permanent residents (green card holders).

Civil Rights in Miami

While Miami wasn't a main center of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, it still experienced changes. Miami was a major city in the southern state of Florida and had a large African American and black Caribbean population.

Miami in the 1980s and 1990s

More Immigration

The Mariel Boatlift in 1980 brought 150,000 Cubans to Miami. Unlike earlier groups, many of these refugees were poor, and some had been released from prisons or mental institutions. During this time, many middle-class non-Hispanic white residents left the city, a trend called "white flight". In 1960, Miami was 90% non-Hispanic white, but by 1990, it was only about 10%.

In the 1980s, Miami also saw more immigrants from other countries, like Haiti. As the Haitian population grew, the area known as "Little Haiti" developed, centered on Northeast Second Avenue and 54th Street. In 1985, Xavier Suarez became the first Cuban mayor of a major U.S. city. In the 1990s, the presence of Haitians was recognized with Haitian Creole signs in public places and on voting ballots.

Another large group of Cubans left Cuba in 1994. To prevent a repeat of the Mariel Boatlift, the Clinton Administration changed U.S. policy. Cubans caught at sea would not be brought to the U.S. but instead taken to U.S. military bases at Guantanamo Bay or Panama. Over 30,000 Cubans and 20,000 Haitians were stopped at sea and sent to camps outside the U.S. during an eight-month period in 1994.

On September 9, 1994, the U.S. and Cuba agreed to normalize migration. This agreement confirmed the U.S. policy of placing Cuban refugees in safe places outside the U.S. Cuba also promised to discourage people from sailing to America. The U.S. committed to allowing at least 20,000 Cuban immigrants per year, plus immediate relatives of U.S. citizens.

On May 2, 1995, a second agreement allowed the Cubans at Guantanamo to enter the U.S. It also created a new policy: Cubans caught at sea would be sent back to Cuba. The Cuban government promised not to punish those who were returned.

These agreements led to the Wet Foot-Dry Foot Policy. Under this policy, Cubans who reached U.S. land ("dry foot") could stay and apply for permanent residence. However, those caught at sea ("wet foot") were sent back unless they could prove they would be persecuted in Cuba. This policy did not apply to Haitians, as the government said they were seeking asylum for economic reasons, not political ones.

Since then, Miami's friendly atmosphere for Latin and Caribbean cultures has made it a popular place for tourists and immigrants from all over the world. It is the third-largest immigration port in the country. Many immigrant communities from Europe, Africa, and Asia have also settled in Miami.

Miami Becomes a Global City

In the 1980s, signs of prosperity appeared all over Miami. Luxury car dealerships, five-star hotels, new apartment buildings, nightclubs, and major businesses began to rise.

Many famous people visited Miami in the 1980s and early 1990s. Pope John Paul II visited in November 1987 and held a large outdoor mass for 150,000 people. Queen Elizabeth II and three U.S. presidents also visited. One of them was Ronald Reagan, who has a street named after him in Little Havana. Nelson Mandela's visit in 1989 caused tensions. Mandela had praised Cuban leader Fidel Castro for his anti-apartheid support. Because of this, Miami city officials withdrew their official welcome. This led to a boycott by the local African American community of Miami's tourist and convention facilities until Mandela received an official greeting. This boycott lasted for months and caused an estimated loss of over $10 million.

Hurricane Andrew (1990s)

In 1992, Hurricane Andrew caused over $20 billion in damage just south of the Miami-Dade area.

The Twenty-First Century

A New Era (2000s)

In 2000, the Elián González affair was a major immigration battle in Miami. It involved six-year-old Elián González, who was rescued off the coast of Miami. The U.S. and Cuban governments, his father, his Miami relatives, and the Cuban-American community were all involved. The main event was on April 22, 2000, when federal agents took Elián, which angered many in the Cuban-American community. During the controversy, Alex Penelas, the mayor of Miami-Dade County, said he would not help the Bill Clinton administration return the boy to Cuba. Tens of thousands of protesters, angry about the raid, filled the streets of Little Havana. Car horns blared, people overturned signs and trash cans, and some small fires were started. Rioters blocked a 10-block area. Soon after, many Miami businesses closed for a day in a boycott against the city, trying to affect its tourism. Employees of airlines, cruise lines, hotels, and major stores participated. Elián González returned to Cuba with his father on June 28, 2000.

In 2003, the controversial Free Trade Area of the Americas negotiations took place. This was a proposed agreement to reduce trade barriers. During the 2003 meeting in Miami, there were many protests against it.

In the late 2000s, Miami saw a huge boom in tall building construction, called a "Miami Manhattanization" wave. Many of the tallest buildings in Miami were finished after 2005. This boom changed the look of downtown Miami, which now has one of the largest skylines in the United States, after New York City and Chicago. This growth slowed after the 2008 global financial crisis, with some projects being put on hold.

In May 2010, construction began on a major project for the Port of Miami, called the Port of Miami Tunnel. It cost about one billion U.S. dollars and was finished in 2014.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Miami para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Miami para niños