History of Unitarianism facts for kids

Unitarianism is a Christian faith that started in the late 1500s in places like Poland and Transylvania. It later grew in England and America. Even though the name "Unitarian" is newer, some of its ideas can be traced back to the very early days of Christianity. This faith became more defined in the mid-1800s, and since then, it has developed differently in various countries.

Contents

Unitarianism's Early History

How Early Christianity Began

Experts say that early Christianity, in its first century, grew out of Judaism. This meant that early Christians strongly believed in one God, just like in Judaism. Many historians think that the idea of the Trinity (God as three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) developed slowly over several centuries. They suggest that the Nicene Council in 325 A.D. and the Athanasian Creed later on were the first times this idea was clearly put into words. One scholar, Jerome H. Neyrey, says that Jesus honored God by following the traditional Jewish understanding of God.

Fourth Century Ideas

In the 300s A.D., a belief called Arianism became popular. It was named after a priest named Arius. This idea suggested that God created Jesus, meaning Jesus was not eternal like God. Even though the Council of Nicea said this idea was wrong in 325 A.D., it remained popular in many parts of the Roman Empire. It was officially banned again in 381 A.D. at another council in Constantinople.

The Protestant Reformation and New Ideas

During the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, many people in Europe started to question the idea of the Trinity. This was called nontrinitarianism. Some people even doubted if famous reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin fully agreed with older Christian beliefs. For example, it's been noted that Luther once questioned parts of the Bible and the word "Trinity."

While these ideas were often suppressed, they eventually led to the formation of separate religious groups in Poland, Hungary, and later, England. Another different idea was Sabellianism. This belief said that God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are not three separate persons, but different ways or "modes" that one God shows himself to believers.

People who followed Unitarianism often shared some key traits: they were very tolerant, studied the Bible historically, focused on fewer essential beliefs, and disliked strict creeds (statements of faith).

Some of the first people to write about these ideas were Martin Cellarius (1499–1564) and Hans Denck (1500–1527). Ludwig Haetzer also had anti-Trinitarian views, but they only became public after he was executed in 1529 for his Anabaptist beliefs. Martin Luther himself was against the Unitarian movement.

Michael Servetus (1511?–1553) greatly influenced these ideas through his writings and his death. In 1531, he wrote a book called De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors About the Trinity). In it, he disagreed with the Nicene idea of the Trinity. He suggested that Jesus was a union of God's divine spirit with a human man, miraculously born from the Virgin Mary. This was seen as a rejection of the Trinity. Servetus even called the Trinity a "three-headed Cerberus" (a mythical dog with three heads) and "three ghosts," saying it caused confusion. He expanded his ideas in another book, Christianismi Restitutio, which led to his burning at the stake in Calvin's Geneva in 1553. Today, many Unitarians see Servetus as an early pioneer and a martyr. His ideas strongly influenced the first anti-Trinitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania. However, his specific views on Jesus were different from later Unitarians.

In 1550, a secret anti-Trinitarian movement began in Italy, led by people like Matteo Gribaldi. Italian exiles then spread these anti-Trinitarian ideas to Switzerland, Germany, Poland, Transylvania, and Holland.

The Dialogues (1563) by Bernardino Ochino discussed problems with the Trinity, which made many people interested. Ochino even pointed to Hungary as a place where religious freedom might be found. Indeed, the first anti-Trinitarian religious communities formed and were tolerated in Poland and Hungary.

Unitarianism's Main Period

Poland's Unitarian Story

Anti-Trinitarian ideas appeared early in Poland. For example, in 1539, an 80-year-old woman named Catherine was burned in Cracow for her beliefs. The first meeting of the Reformed Church (Calvinist) in Poland was in 1555. At the second meeting in 1556, leaders like Grzegorz Paweł z Brzezin and Peter Gonesius challenged traditional ideas, influenced by Servetus and Italian anti-Trinitarians. When Giorgio Biandrata arrived in 1558, he became a temporary leader for this group.

The word "Unitarian" first appeared in a document in Transylvania in 1600, but it wasn't widely used there until 1638. The Polish Brethren started as a group of Arians and Unitarians who separated from the Polish Calvinist Church in 1565. By 1580, the Unitarian ideas of Fausto Sozzini (which led to the term Socinianism) became the most common. Sozzini's grandson, Andrzej Wiszowaty Sr., published a collection of their works called Library of the Polish Brethren who are called Unitarians (1665–69). The name "Unitarian" was brought to England in 1673.

In 1565, a Polish assembly decided to exclude anti-Trinitarians from the main Reformed Church. So, Unitarians started their own meetings, calling themselves the Ecclesia minor (Minor Church). They were also known as Polish brethren or Arians. This group never called itself anything other than "Christian." At first, they were Arian and Anabaptist, but by 1588, they adopted the views of Fausto Paolo Sozzini. Sozzini had moved to Poland in 1579. He did not believe that Jesus existed before his birth, but he did accept the virgin birth.

In 1602, a nobleman named Jakub Sienieński set up the Racovian Academy and a printing press for the anti-Trinitarian community in Raków, Kielce County. From this press, the Racovian Catechism was published in 1605. However, a Catholic backlash began in 1610. The establishment at Raków was shut down in 1638 after two boys supposedly threw stones at a crucifix outside the town.

For 20 years (1639–1659), the Arians were tolerated. But public opinion turned against them, especially because they were seen as helping Sweden during a war. In 1660, the Polish assembly gave anti-Trinitarians a choice: change their beliefs or leave the country. Many Polish nobles were part of the Minor Church, but Sozzini's views, which said Christians shouldn't hold government positions, made them politically weak.

The order to leave was carried out in 1660. Some people changed their beliefs, but many went to the Netherlands. Others, like Christopher Crell, went to Germany, Prussia, and Lithuania. A group settled in Transylvania, where they kept their own organization until 1793.

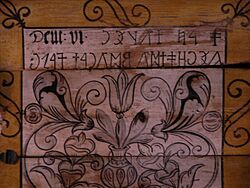

The refugees in Amsterdam published the Bibliotheca fratrum polonorum (1665–1669). This collection included works by their main theologians. The title page of this collection, which said quos Unitarios vocant (who are called Unitarians), introduced the term "Unitarian" to Western Europe.

Unitarianism in Transylvania and Hungary

Anti-Trinitarian ideas in Transylvania really began when Giorgio Biandrata arrived at the court in 1563. He influenced Ferenc Dávid (1510–1579), who had been a Catholic, then Lutheran, then Calvinist, and finally an anti-Trinitarian. Some believe that the growth of anti-Trinitarian views in Transylvania and Hungary might have been partly due to the increasing influence of the Ottoman Empire and Islam at that time.

In 1564, Dávid was chosen by the Calvinists as "bishop of the Hungarian churches in Transylvania." He also became the court preacher for John Sigismund, the prince of Transylvania. Dávid started discussing the Trinity in 1565, first questioning the idea of the Holy Spirit as a separate person.

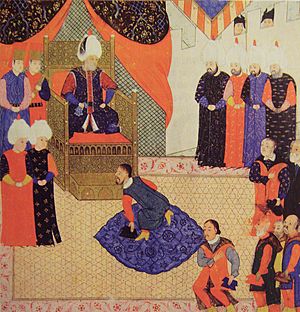

His main opponent in public debates was the Calvinist leader, Peter Melius. His supporter was Biandrata. Prince John Sigismund agreed with Dávid's views. In 1568, he issued an edict of religious liberty at the Diet of Torda. This allowed Dávid to move his leadership from the Calvinists to the anti-Trinitarians.

When John Sigismund died in 1571, Stephen Báthory, a Catholic, became prince. Influenced by Johann Sommer, Dávid stopped worshiping Christ around 1572. This caused problems. Dávid was tried as an innovator and died in prison in 1579. The worship of Christ became a standard practice in the Unitarian Church.

The term unitaria religio (Unitarian religion) first appeared in a decree in 1600. However, the church didn't officially adopt the name "Unitarian" until 1638.

In 1618, the Unitarian Church condemned a group called the Szekler Sabbatarians, who had Jewish-like beliefs. This group continued until the 1840s, with many converting to Judaism. In 1626, the Disciplina ecclesiastica was published by Bishop Bálint Radeczki. In 1638, the Accord of Dés led to the suppression of Unitarians.

Among the many bishops, George Enyedi (1592–1597) was famous for his writings, and Mihály Lombard de Szentábrahám (1737–1758) helped rebuild the church after persecution. His book, Summa Universae Theologiae Christianae secundum Unitarios (published 1787), was accepted as the official statement of faith.

The first high school in Transylvania was founded in the late 1700s in Székelykeresztúr. It still operates today as a state school.

Today, the official name in Hungary is the Hungarian Unitarian Church, with about 25,000 members. In Romania, there is a separate church called the Unitarian Church of Transylvania with about 65,000 members, especially among the Székely people. In the past, the Unitarian bishop had a seat in the Hungarian parliament. The main college for both churches is in Cluj-Napoca.

Until 1818, English Unitarians didn't know much about this church. After that, they became close. Many students from Transylvania later studied theology at Manchester College in Oxford.

Unitarianism in England

In England, Unitarianism was a Protestant group with roots in the Anabaptist radicals of the English Civil War. They believed in adult baptism and a republican government. They were egalitarians who wanted to promote revolutionary ideas. The movement became popular among nonconformists (Protestants who didn't follow the Church of England) in the early 1700s. Many English Presbyterians were drawn to Norwich because of its growing scientific community.

Unitarianism began to form as a proper denomination in 1774. That year, Theophilus Lindsey and Joseph Priestley started the first openly Unitarian church in England, the Essex Street Church in London. In 1791, Lindsey and John Disney created the first organized Unitarian society, focused on spreading Christian knowledge. This was followed by The Unitarian Fund (1806), which supported missionaries and poorer churches. Unitarianism was not fully legal in the United Kingdom until the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813. This law was largely pushed by William Smith. Even after this, Unitarians didn't have full civil rights. So, in 1819, a third Unitarian society was formed to protect their civil rights. In 1825, these three groups combined to form the British and Foreign Unitarian Association. A century later, this joined with the Sunday School Association to become the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches, which is still the main organization for British Unitarianism today.

Early Challenges

Between 1548 and 1612, there were few anti-Trinitarians in England. Most of them were either executed or forced to change their beliefs. Those who were burned included George van Parris (1551), Patrick Pakingham (1555), Matthew Hamont (1579), John Lewes (1583), Peter Cole (1587), Francis Kett (1589), Bartholomew Legate (1612), and Edward Wightman (1612). In most of these cases, the anti-Trinitarian ideas came from Holland. The last two executions happened after the Latin version of the Racovian Catechism was dedicated to King James I in 1609.

Socinian Influence

Fausto Sozzini died in 1604, but the Racovian Academy and its printing press continued until 1639. They influenced England through the Netherlands.

Socinian ideas became popular, especially among men like Lucius Cary, 2nd Viscount Falkland and Chillingworth. This led to an attempt in 1640 to ban Socinian books. In 1648, a law made denying the Trinity a crime punishable by death. However, this law was rarely enforced, as Cromwell intervened in cases like Paul Best and John Biddle.

From 1652 to 1654 and 1658 to 1662, Biddle held secret Socinian meetings in London. He also reprinted and translated the Racovian Catechism. His follower, Thomas Firmin, a merchant and helper of the poor, promoted many writings between 1690 and 1699.

In England, the "Socinian controversy" started by Biddle came before the "Arian controversy" started by Samuel Clarke's book in 1712. Arian or semi-Arian views were very popular in the 1700s, both in the Church of England and among other Protestant groups.

The Term "Unitarian" in 1673

The word "Unitarian" was used in private letters in England, referring to imported books like the Library of the Polish Brethren who are called Unitarians (1665). Henry Hedworth was the first to use "Unitarian" in print in English in 1673. The word first appeared in a book title in Stephen Nye's A brief history of the Unitarians, called also Socinians (1687). It was used broadly to describe anyone who believed in the single nature of God.

Act of Toleration 1689

The first preacher to call himself Unitarian was Thomas Emlyn (1663–1741), who started a congregation in London in 1705. This was against the Act of Toleration 1689, which excluded anyone who preached against the Trinity.

In 1689, Presbyterians and Independents joined forces, agreeing to drop their names and support a common fund. This union broke apart in 1693. Over time, differences in how funds were managed led to the Presbyterian name being linked to more liberal theological views.

Salters' Hall Conference 1719

The open environment of dissenting academies (colleges) encouraged new ideas. The Salters' Hall conference in 1719, called because of the views of James Peirce, allowed dissenting congregations to decide their own beliefs. Leaders who supported a purely human view of Jesus came mostly from the Independents, such as Nathaniel Lardner, Caleb Fleming, Joseph Priestley, and Thomas Belsham.

Isaac Newton was also an anti-Trinitarian and possibly a Unitarian. One of his last visitors before he died in 1727 was Samuel Crellius from Lithuania.

The Unitarian Church in 1774

The formation of a distinct Unitarian denomination began in 1773 when Theophilus Lindsey (1723–1808) left the Anglican Church. This happened after a petition to parliament to allow clergy to avoid signing Anglican doctrinal articles failed. Lindsey's departure was followed by others, though many left the ministry entirely. Lindsey's hope for a large Unitarian movement from the Anglican Church was not fully met. The church he started at Essex Street Chapel, with help from ministers like Joseph Priestley and Richard Price, became a center for change. Legal issues were resolved with the help of lawyer John Lee. Over time, Lindsey's type of theology replaced Arianism in many dissenting churches.

The Act of Toleration 1689 was changed in 1779, replacing the requirement to believe in Anglican articles with a belief in Scripture. In 1813, laws against those who denied the Trinity were removed by the Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813, largely thanks to William Smith, a Member of Parliament and abolitionist. In 1825, the British and Foreign Unitarian Association was formed by combining three older societies.

Unitarian properties faced attacks, especially those established before 1813. The Wolverhampton Chapel case began in 1817, and the more important Hewley Fund case in 1830. Both were decided against the Unitarians in 1842. An appeal to parliament resulted in the Dissenters' Chapels Act (1844). This law protected churches where trusts didn't specify doctrines, meaning 25 years of use made the current practices legal.

Less Focus on Miracles

In the 1700s, a leading Unitarian theologian, Joseph Priestley (who also discovered oxygen), believed God performed many miracles. Priestley said that "no facts, in the whole compass of history, are so well authenticated as those of the miracles, the death, and the resurrection of Christ."

However, from 1800 to 1850, the British Unitarian movement shifted. They started questioning the miraculous, the idea that the Bible was directly inspired by God, and the virgin birth. They still believed in the resurrection of Christ at this point.

American Influence

During the 1800s, the Unitarianism of Priestley and Belsham, which was tied to a philosophy of determinist (the idea that all events are determined by prior causes), was changed by the ideas of William Ellery Channing from America. His works were widely read. Another American influence was Theodore Parker, who helped reduce the strict supernaturalism of earlier Unitarians. In England, the teachings of James Martineau also became very important.

Famous People and Institutions

English Unitarianism produced some well-known scholars, such as John Kenrick and Samuel Sharpe. For training its ministers, it supported Manchester College at Oxford and the Unitarian Home Missionary College. It also produced famous political families like the Chamberlain family (Joseph, Austen, and Neville Chamberlain) and industrialist families like the Courtauld and Tate dynasties.

Important Publications

English Unitarian magazines started with Priestley's Theological Repository (1769–1788). Other important publications included the Monthly Repository (1806–1838) and The Hibbert Journal. The Hibbert Trust, founded by Robert Hibbert, supported scholarships, lectures, and a chair of ecclesiastical history at Manchester College.

Unitarianism in Scotland

The execution of student Thomas Aikenhead in Edinburgh in 1697 for speaking against the Trinity is well-known. The writings of John Taylor on original sin and atonement were very influential in eastern Scotland. Some ministers were suspected of similar heresies. Open Unitarianism has never been very popular in Scotland. The oldest Unitarian church in Scotland is in Edinburgh, founded in 1776.

The Scottish Unitarian Association was founded in 1813. The McQuaker Trust was founded in 1889 to spread Unitarian ideas.

One reason Unitarianism was relatively weak in Scotland in the early 1800s might be the continued presence of conservative, Bible-focused anti-Trinitarian, Arian, and Socinian views in other churches. These Scottish anti-Trinitarians were often more similar to earlier Unitarians than to the more liberal views of their time. For example, the first congregations following John Thomas's Socinian and Adventist teachings in 1848-1849 were mostly Scottish.

Currently, there are four Unitarian churches in Scotland: Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh, and Glasgow.

Unitarianism in Ireland

Controversy about the Trinity started in Ireland when Thomas Emlyn was prosecuted in Dublin in 1703. He was fined and imprisoned for rejecting the idea of Christ's divinity. In 1705, the Belfast Society was founded for theological discussions by Presbyterian ministers in the north. This led to many people disagreeing with signing the Westminster standards (a set of religious beliefs). Tolerance for dissenters was granted in Ireland in 1719 without requiring any doctrinal signing. The next year, a movement against signing beliefs began in the General Synod of Ulster. This led to the supporters of non-signing, led by John Abernethy, forming their own presbytery (a group of churches) in 1725. This Presbytery of Antrim was excluded in 1726. For the next hundred years, its members greatly influenced their fellow synod members. However, the influence of the Scottish Seceders (from 1742) caused a reaction. The Antrim Presbytery gradually became Arian. The Southern Association, known since 1806 as the Synod of Munster, was also affected by this type of theology. From 1783, ten of the fourteen presbyteries in the Synod of Ulster made signing beliefs optional. The synod's rules in 1824 left "soundness in the faith" to be checked by signing or by examination. Henry Cooke strongly opposed this compromise and succeeded in defeating his Arian opponent, Henry Montgomery, in 1829. Montgomery led a group that formed the Remonstrant Synod of Ulster in 1830, which included three presbyteries.

In 1910, the Antrim Presbytery, Remonstrant Synod, and Synod of Munster united to form the General Synod of the Non-subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland. This church had 38 congregations. Until 1889, they had two theological professors in Belfast, where John Scott Porter was a pioneer in biblical criticism. After that, they sent their students to England for theological education. However, their views and practices remained more conservative than those of their English counterparts in some ways. Irish Unitarian magazines began in 1832 with the Bible Christian.

Unitarianism in the United States

The history of Unitarian thought in the United States can be divided into four main periods:

- Early movements (early 1700s to around 1800)

- The shaping period (around 1800–1835)

- A period influenced by Transcendentalism (around 1835–1885)

- The modern period (since 1885)

Early Movements and Unitarianism

Unitarianism in the United States developed similarly to England. It went through stages of Arminianism (belief in free will), Arianism, rationalism, and then a modernism that accepted ideas from the study of all religions. In the early 1700s, Arminianism appeared in New England. This trend was sped up by a reaction against the "Great Awakening" led by Jonathan Edwards. Before the War of Independence, Arianism appeared in individual cases. French ideas of deism (belief in a God who created the universe but does not intervene in it) were also widespread, though not organized into religious groups.

By the mid-1700s, Harvard College represented some of the most advanced thinking of the time. Many clergymen in New England preached what was essentially Unitarianism. The most famous was Jonathan Mayhew (1720–1766), a pastor in Boston, Massachusetts. He preached about the strict unity of God, that Christ was subordinate to God, and that salvation came from good character. Charles Chauncy (1705–1787), a pastor in Boston, was a main opponent of Edwards in the Great Revival. He was both a Unitarian and a Universalist (someone who believes all people will eventually be saved). Other Unitarians included Ebenezer Gay of Hingham and Samuel West of New Bedford.

The first official acceptance of the Unitarian faith by a church was by King's Chapel in Boston. They appointed James Freeman (1759–1835) as their pastor in 1782 and changed their prayer book to a mild Unitarian liturgy in 1785. Rev. William Hazlitt (father of the essayist) visited the United States from 1783–1785 and reported that there were Unitarians in Philadelphia, Boston, Charleston, South Carolina, and other places. Unitarian churches were started in Portland and Saco, Maine in 1792. In 1800, the First Church in Plymouth—the church founded by the Pilgrims in 1620—accepted the more liberal faith. Joseph Priestley moved to the United States in 1794 and started Unitarian churches in Northumberland, Pennsylvania that year and in Philadelphia in 1796. His writings were very influential.

So, from 1725 to 1825, Unitarianism grew in New England and elsewhere. The first clear sign of this change was the appointment of Henry Ware (1764–1845) as a professor of divinity at Harvard College in 1805.

By the early 1800s, almost all the churches in Boston had Unitarian preachers. New Unitarian churches were also established in New York City, Baltimore, Washington, and Charleston during this time.

Shaping Period

The next period of American Unitarianism, from about 1800 to 1835, was a shaping period. It was mainly influenced by English philosophy, somewhat supernatural, and focused on helping others and practical Christianity. Dr. William Ellery Channing was its most famous leader.

The first official acceptance of the Unitarian faith by a church in America was by King's Chapel in Boston, which appointed James Freeman as its pastor in 1782 and changed its Prayer Book in 1785. In 1800, Joseph Stevens Buckminster became a minister in Boston. His sermons and interest in German "New Criticism" helped shape Unitarianism in New England. Unitarian Henry Ware was appointed as a professor at Harvard College in 1805. Harvard Divinity School then started teaching Unitarian theology. Buckminster's close friend William Ellery Channing (1780–1842) became pastor of the Federal Street Church in Boston in 1803. In a few years, he became the leader of the Unitarian movement. His sermons, like "Unitarian Christianity" in 1819, made him a key interpreter of Unitarianism.

The "Unitarian Controversy" in 1815 led to a growing split in the Congregational churches. This was made clearer in 1825 with the formation of the American Unitarian Association in Boston. Its goal was "to spread the knowledge and promote the interests of pure Christianity." It published books, supported poor churches, sent missionaries, and started new churches. The Unitarian movement grew slowly, and its influence was mainly through general culture and literature. Many of its ministers were trained in other denominations. The Harvard Divinity School was Unitarian from 1816 until 1870, when it became non-sectarian. The Meadville Lombard Theological School was founded in 1844, and the Starr King School for the Ministry in 1904.

The first school founded by Unitarians was the Clinton Liberal Institute in New York in 1831.

Influence of Transcendentalism; Reaction

A third period (from about 1835 to 1885) was deeply influenced by German idealism. It became more rational, though its theology still had a mystical flavor. As a reaction, the National Unitarian Conference was formed in 1865. It adopted a clearly Christian platform, stating its members were "disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ."

The more rational minority then formed the Free Religious Association. This group aimed "to encourage the scientific study of theology and to increase fellowship in the spirit." The Western Unitarian Conference later took a similar stance, basing its "fellowship on no dogmatic tests." It aimed "to establish truth, righteousness and love in the world." This conference also said that believing in God was not a necessary part of Unitarian belief.

This period of debate and strong theological development ended around 1885. This was confirmed by the national conference in Saratoga Springs, New York, in 1894. They voted almost unanimously that: "These churches accept the religion of Jesus, holding, in accordance with his teaching, that practical religion is summed up in love to God and love to man." They also welcomed anyone who, despite different beliefs, shared their spirit and goals. The leaders of this period were Ralph Waldo Emerson with his idealism and Theodore Parker with his view of Christianity as an absolute religion.

Modern Period

The fourth period, starting around 1885, has been one of rationalism, acceptance of universal religion, and a strong embrace of scientific methods and ideas. It has also focused on an ethical effort to live out the higher ideals of Christianity. This period has seen general harmony, steady growth in the number of churches, and a wider connection with other similar movements.

This phase was shown by the formation of The International Council of Unitarian and other Liberal Religious Thinkers and Workers in Boston on May 25, 1900. Its goal was "to open communication with those in all lands who are striving to unite pure religion and perfect liberty, and to increase fellowship and co-operation among them." This council has held meetings in London, Amsterdam, Geneva, and Boston. After 1885, Emerson's influence became very strong, modified by the more scientific preaching of Minot Judson Savage, who was guided by Darwin and Spencer.

Beyond its own borders, the Unitarian movement gained recognition through the public work of people like Henry Whitney Bellows and Edward Everett Hale. The number of Unitarian churches in the United States in 1909 was 461, with 541 ministers. The church membership was estimated at 100,000.

In 1961, the American Unitarian Association merged with the Universalist Church of America. This formed the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA).

Today, Unitarian Universalism is not strictly Unitarian in its theology. Despite its name, this denomination does not necessarily promote belief in one God or universal salvation. It is simply the heir to the Unitarian and Universalist church system in America. While there are Unitarians within the UUA, there is no specific belief or doctrine that members must agree to. This makes it very different from many other faith groups. Most Unitarian Universalists today do not identify as Christians. Jesus and the Bible are seen as important sources of inspiration, along with holy people and traditions from around the world. Unitarian Universalists base their community on a set of Principles and Purposes, rather than on a prophet or a creed. Famous Unitarian Universalists include Tim Berners-Lee (founder of the World Wide Web) and Pete Seeger.

The decline of specifically Christian theology in Unitarian churches in the United States has led to several revival movements. Unitarian Christians within the UUA formed the Unitarian Universalist Christian Fellowship (UUCF) in 1945. This was a group within the UUA specifically for Christians, who were becoming a minority. Similarly, the American Unitarian Conference (AUC) was founded in 2000. Unlike the UUCF, the AUC remains outside the UUA. The AUC's mission is "renewal of the historic Unitarian faith." It promotes a set of God-centered religious principles but does not force a creed on its members.

Unitarians in America, because of these changes, have generally taken one of three paths to find communities where they can worship God. Some have stayed within the Unitarian churches, accepting their non-Christian nature, but found their needs met in the UUCF. Some Unitarians felt that the main UUA churches were not accepting of Christians, or that the larger Unitarian Universalist organizations were becoming too focused on politics and liberal ideas to be considered a religious movement. These people decided to join the American Unitarian Conference. Most Christian Unitarians have sought out liberal Christian churches in other denominations and found homes there.

Unitarianism in Canada

Unitarianism came to Canada from Iceland and Britain. Some Canadian churches even held services in Icelandic until recently. The first Unitarian service in Canada was held in 1832 by a minister from England, Rev. David Hughes. The Montreal congregation, founded in 1842, called its first permanent minister, Rev. John Cordner, from Ireland. He arrived in 1843 and served for 36 years. Then, in 1845, a congregation in Toronto was founded. Other churches formed in Hamilton (1889), Ottawa (1898), Winnipeg (1891), Vancouver (1909), and Victoria (1910). Canadian churches were connected to the British association until World War II, when their ties to Unitarians in the United States became stronger.

Universalism came to Canada in the 1800s, mostly with settlers from the United States. The Universalist ideas of universal reconciliation (everyone will be saved), a loving God, and the brotherhood of all people were welcomed by those who didn't like the idea of predestination (God deciding who is saved before they are born). Universalist churches formed mostly in rural towns in Quebec, the Maritimes, and southern Ontario. Universalism in Canada declined, similar to the United States. Today, the three remaining churches are part of the Canadian Unitarian Council (CUC).

The CUC was formed on May 14, 1961, one day before the UUA in the United States. The two groups worked closely together until financial and other issues led to greater independence. In 2002, the CUC started providing direct services to Canadian churches that were previously handled by the UUA. The UUA still helps CUC churches find ministers.

The Unitarian Service Committee, created during World War II for overseas relief, continues today as a separate agency called USC Canada. It gets support from across Canada for its humanitarian work worldwide.

The first ordination of a Canadian Unitarian minister after the CUC and UUA separated was in Victoria, British Columbia, in 2002. Rev. Brian Kiely, who gave the ordination sermon, jokingly said that Canadian Unitarianism is like a doughnut: the richness is in the circle of fellowship, not a strict set of beliefs.

Unitarianism in the Modern Era

20th Century Developments

In 1928, the British and Foreign Unitarian Association merged with the Sunday School Association. They had shared offices for decades. This new group became the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches. The General Assembly is still the main organization for British Unitarianism, with its headquarters in central London.

21st Century Challenges

In May 2004, Rev. Peter Hughes, a Unitarian minister, wrote an article and gave an interview where he warned that the Unitarian Church might be disappearing. According to The Times, "the church has fewer than 6,000 members in Britain; half of whom are aged over 65." He noted that some older churches had no minister for decades. However, the denomination's president, Dawn Buckle, disagreed. She described it as a "thriving community capable of sustaining growth." There are more than 180 Unitarian churches in Britain as part of the General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches.

Separate from the General Assembly, there are other groups that look back to earlier forms of Unitarianism. This includes groups that follow the ideas of early Polish, Dutch, and English "Socinians" from the 1600s, such as the Restoration Fellowship. Others look to the later "Biblical Unitarianism" of Robert Spears. Many of these groups do not believe in the Trinity. They are often liberal in some political areas, like conscientious objection (refusing to serve in the military for moral reasons), but they are very traditional about the Bible. They are also conservative on topics like homosexuality. However, some of these groups do have women ministers.

Recently, some religious groups have started using the term "Biblical Unitarianism" to show that their beliefs are different from modern, more liberal Unitarianism.

Unitarianism Spreads to Other Countries

Germany

There are currently five separate groups of Unitarians in Germany:

- The Unitarische Freie Religionsgemeinde (Unitarian Free Religious Community) was founded in 1845 in Frankfurt am Main.

- The Religionsgemeinschaft Freier Protestanten ("Religious Community of Free Protestants") was formed in 1876. In 1911, their newspaper used the subtitle "German Unitarian Gazette." After World War II, several groups with close ties to certain political ideologies started migrating to this group and influencing its decisions. Most of the original "Free Protestants" then left. In 1950, the group changed its name to Deutsche Unitarier Religionsgemeinschaft ("German Unitarian Religious Community"). It is the only Unitarian group in Germany that belongs to the ICUU.

- The Unitarische Kirche in Berlin (Unitarian Church in Berlin) was founded in 1948.

- The Christliche Unitarier (Christian Unitarians) is a Unitarian-Christian group in Germany and Austria founded in 2018.

- The Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Frankfurt is an international, English-speaking liberal religious community. It is part of the European Unitarian Universalists.

Denmark

In 1900, Det fri Kirkesamfund (The Free Congregation) was founded by liberal Christians in Copenhagen. Since 1908, this church has been separate from the Folkekirke (the Danish Lutheran state church). In Aarhus, another Unitarian church was founded by the Norwegian Unitarian pastor Kristofer Janson (1841–1917), but it has since closed. The Icelandic theologian Magnús Eiríksson (1806–1881), who lived in Copenhagen, is often seen as a spiritual pioneer for the Unitarian movement in Denmark.

Sweden

Inspired by the writings of Theodore Parker, the Swedish writer Klas Pontus Arnoldson founded the Unitarian association Sanningssökarna ("The Truth Seekers") in Gothenburg in 1871. This association also published a magazine. Two other Unitarian associations were founded in 1882. In 1888, Unitarians asked the Swedish King for permission to start another association but were denied because Unitarianism was not considered a Christian religion. Later, many Unitarians turned to theosophy. In 1974, members of The Religion and Culture Association in Malmö founded The Free Church of Sweden. In 1999, the church changed its name to The Unitarian Church in Sweden.

Norway

In 1892 and 1893, Norwegian Unitarian ministers Hans Tambs Lyche and Kristofer Janson returned from America and started introducing Unitarianism. In 1894, Tambs Lyche tried to organize a Unitarian Church in Oslo but failed. However, he published Norway's first Unitarian magazine. In January 1895, Kristofer Janson founded The Church of Brotherhood in Oslo, which was the first Unitarian church. He stayed there for three years. In 1904, Herman Haugerud returned to Norway from America and became the last Unitarian pastor to The Unitarian Society (as The Church of Brotherhood was renamed). Pastor Haugerud died in 1937, and the Unitarian church stopped existing shortly after. Between 1986 and 2003, different Unitarian groups were active in Oslo. In 2004, these merged into The Unitarian Association, which registered as a religious society in 2005 under the name The Unitarian Association (The Norwegian Unitarian Church). Later, "Bét Dávid" was added to the name: The Bét Dávid Unitarian Association (The Norwegian Unitarian Church). This church is similar to both Transylvanian Unitarianism and Judaism, hence "bét" (Hebrew for "house") and "Dávid" (the name of the first Transylvanian Unitarian bishop Dávid Ferenc). In 2006, this church joined the International Council of Unitarians and Universalists (ICUU). Since 2007, there is also a Unitarian Universalist Fellowship in the Oslo area, separate from The Norwegian Unitarian Church.

Spain

Although the pioneer and first martyr of European Unitarianism, Michael Servetus, was Spanish, the Spanish Inquisition and the strong influence of the Roman Catholic Church prevented any Unitarian Church from developing in Spain for centuries.

This situation began to change in the 1800s. A liberal Spanish writer and former priest, José María Blanco-White, became a Unitarian during his time in England and remained so until his death in 1841. At the end of the century, a group of liberal Spanish thinkers called the Krausistas admired American Unitarian leaders William Ellery Channing and Theodore Parker. They wished for more natural religion and religious rationalism in Spain, but they did not create any liberal church to push this forward.

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) stopped any hopes for change in Spain for several decades. After the death of dictator Francisco Franco and the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, religious freedom was finally established in Spain. In 2000, the Sociedad Unitaria Universalista de España (SUUE) was founded in Barcelona. In 2001, it became a member of the International Council of Unitarians and Universalists (ICUU). In 2005, it changed its name to the Unitarian Universalist Religious Society of Spain to gain legal status as a religious organization, but the application was rejected.

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |